As we noted in Proceedings last year, leaders in the Pentagon, on Capitol Hill, and in industry all agree: We must accelerate innovative research and development, acquire new capabilities faster, and transform the way the U.S. military fights in order to implement our defense strategy.

Before major changes to Navy shipbuilding are proposed, all stakeholders should have a fulsome discussion of the business of Navy shipbuilding and implications of big changes. There are a range of options available to transition from an existing shipbuilding program to a new program. Each option has trade-offs and requires careful consideration that takes into account the realistic schedule needed to mature new designs and technologies, develop new tooling and facilities, and adapt the workforce in advance of starting construction on a new shipbuilding program.

Navy Shipbuilding Is Different

Large Navy warships typically take longer to build, have higher unit costs, have more suppliers, and are more technologically complex when compared with other U.S. weapons systems. In addition, there is a small domestic U.S. market for large U.S.-built ships, which largely centers on ships required for domestic trade by the Jones Act. So, the Navy is often the only customer for large new ships in the United States.

The procurement of U.S. Navy warships is a marketplace with revenues of roughly $20 billion annually. Four major prime contractors build large Navy warships and, with their subcontractors and other government-directed contractors, receive the vast majority of this revenue. The economic term for this situation, in which there is a single buyer and multiple sellers, is a monopsony.

Typically, a buyer who has a monopsony has a significant leverage in negotiating lower prices for goods, labor wages, and costs for materials because of the heightened competition among sellers for the buyer’s business.

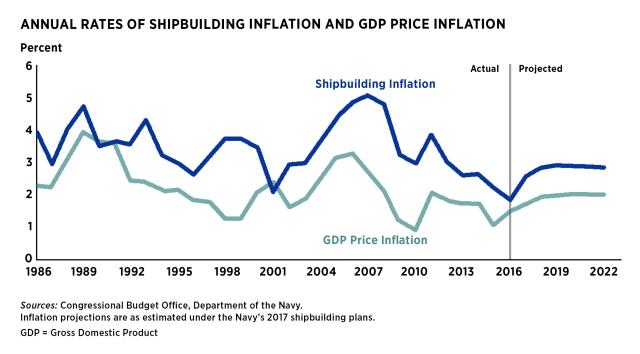

With competition limited because of low volumes, specialized construction needs, and high barriers to enter the market, Navy shipbuilding often fails to realize the benefits of being a monopsony. Between 1986 and 2016, the Navy procured an average of just 8.5 battle force ships per year, and the Navy shipbuilding cost index, which measures growth in the costs of labor and materials in the shipbuilding sector, outpaced general economic inflation by approximately 1.2 percentage points per year. To maintain the Navy’s shipbuilding buying power, annual Navy shipbuilding budget requests need to account for cost increases in the shipbuilding sector.

Contraction and Specialization of Prime Contractors

Since the 1960s, 14 U.S. shipyards that construct ships for the Navy have closed, and three have left the defense industry. Only one new shipyard has opened.As a result, just seven shipyards, owned by four prime contractors, build large Navy warships today.

By comparison, China has more than 20 shipyards supporting its naval surface ship expansion, with dozens of commercial shipyards that dwarf the largest U.S. shipyards in size and throughput. All Chinese naval construction shipyards also build commercial ships, which provide additional revenue and support shipyard design, workforce, and infrastructure development while reducing overhead costs for naval construction. The Chinese Navy is growing at an annual rate of 10 ships and is expected to reach 460 ships in 2030, compared with the U.S. Navy which has roughly 300 ships and is struggling to replace decommissioning ships to avoid shrinking.1

Among the seven large U.S. Navy shipyards, ship-class specialization is the norm. Following the award of the lead ship in the class, sole-source contractual arrangements exist, literally or in principle, for nearly all classes of large U.S. Navy warship being procured: aircraft carriers, submarines, amphibious ships, auxiliary ships, and small surface combatants. This situation, in which there is only one seller (the shipbuilder of a class of vessels) and one buyer (the Navy), is called a bilateral monopoly and the pricing of ships is determined through negotiation rather than competition.

The only example of regular competition is the Arleigh Burke–class guided-missile destroyer program, where two shipyards compete to build a common design. In this case and few others (e.g., certain lead-ship awards for new classes of vessels) in which competition exists, the Navy does reap benefits on labor and material prices when it is the only buyer.

Over time, the Navy and its prime contractors have made substantial capital and workforce investments in their shipyards and, increasingly, in their suppliers, to meet the Navy’s projected shipbuilding needs. These investments typically have the effect of increasing specialized tooling, equipment, and facilities, which in turn makes a shipyard better at building existing product lines but may reduce competitiveness for new work that differs from existing product lines.

Importance of Predictability and Stability

Maximizing stability in the shipbuilding industrial base, which includes prime contractors, subcontractors, and suppliers, as well as improving affordability for the Navy and taxpayers requires stable, predictable procurement profiles and intervals between ships (e.g., 12 months between ship construction starts). Consistent intervals enable prime contractors to execute ship fabrication more efficiently and suppliers to produce components and subsystems more efficiently. The result is often an increased shipbuilder learning curve, which translates into fewer labor hours on successive ships of the same class, as well as better material and supplier pricing, all of which reduces the time needed to build the ship and cost of the ship to the Navy and taxpayers.

Stability and predictability also enable multiple-ship, multiple-year procurement contracts for shipbuilding programs, which have saved taxpayers billions of dollars, accelerated ship deliveries, and strengthened the industrial base. We believe the continued use of multiple-ship, multiple-year contracts for mature shipbuilding programs should receive thorough consideration.

Once a shipbuilding rate is set (e.g., buying two ships of a class per year), it can be just as challenging for the shipbuilding industrial base to speed up (e.g., buying three ships of that class per year) as it is to slow down. Often, even with significantly more funding and a commitment to sustain higher funding over time, it takes several years for a shipyard to configure for the higher production rate, hire and train the additional shipbuilders, and increase supplier deliveries. As a result, prior to a rate change or introducing a new shipbuilding product line at a shipyard, Defense and Navy leaders must recognize that doing so will be a long-term commitment with that shipyard and its suppliers and require stable and predictable funding for several years to come.

Contraction and Specialization of Suppliers

Over the past 25 years, the number of Navy shipbuilding suppliers for nuclear-powered submarines and aircraft carriers dropped by more than two-thirds, and more than 65 percent of remaining suppliers are the single‐ or sole‐source for their product. This sharp contraction occurred after the Navy dropped from procuring four submarines per year in 1977 through 1996 to just one submarine per year in 1998 through 2010 (with the exception of zero submarines being procured in 2000).

Expanding the shipbuilding supplier base is not easy and cannot happen quickly. As former Ingalls Shipbuilding President Brian Cuccias testified, “Qualifying to be a supplier is a difficult process. Depending on the commodity, it may take up to 36 months. That is a big burden on some of these small businesses. This is why creating sufficient volume and exercising early contractual authorization and advance procurement funding is necessary to grow the supplier base. . . Many of our suppliers are small businesses and can only make decisions to invest in people, plant and tooling when they are awarded a purchase order.”

Importance of Deliberate Future Planning

Over time, the highly specialized, low competition Navy shipbuilding process has become codependent. Given there is often only one shipyard capable of building a class of ships for the Navy, the Navy relies on this shipbuilder to meet its force-structure requirements.

Similarly, without the Navy placing orders for this class of ships, the shipbuilder and its suppliers will lose a line of business and possibly their entire business. In addition to layoffs of the shipbuilder’s skilled workforce, many of whom have readily transferrable skill sets to other industries, shipbuilding production breaks often have outsized ripple effects through the suppliers, particularly small companies that are ill-equipped to absorb large fluctuations in purchase orders.2

As a result, transition planning from one class of ships to the next is critical. With a number of new ship classes on the horizon, the Defense strategy under review, and Navy fleet requirements being re-assessed, Department of Defense leaders must now consider and plan for how best to transition from existing Navy shipbuilding production lines, if necessary, to support the fleet of the future. This planning should include acquisition strategies that incorporate engineering-based technology development efforts.

In reviewing shipbuilding programs, there are four basic options (in increasing order of cost and impact to the government and shipbuilder):

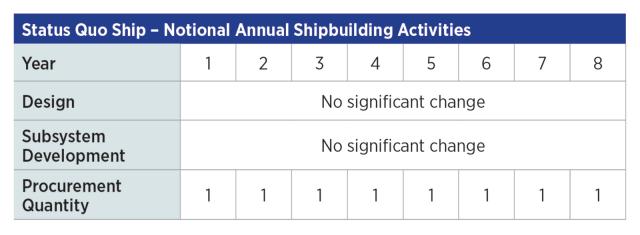

- Status quo: Continue the current shipbuilding program without significant changes to the design, subsystems, facilities, workforce, or suppliers;

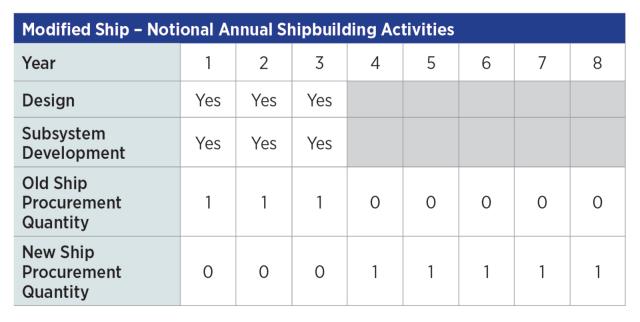

- Modified ship: Modify the current ship with changes to the existing design, subsystems, facilities, workforce, and/or suppliers:

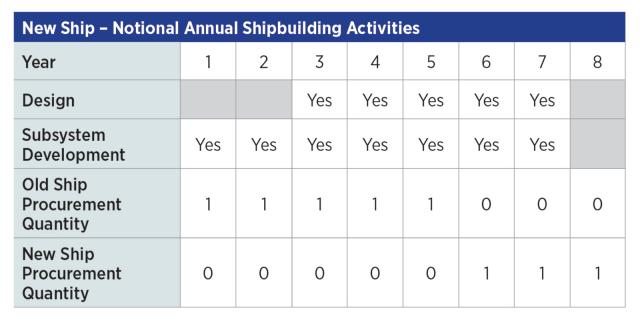

- New ship: Build a new ship with a different design, subsystems, and significant changes to the facilities, workforce, and/or suppliers;

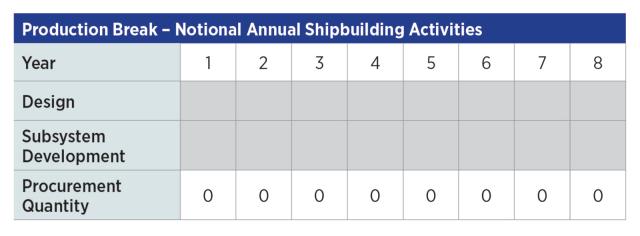

- Production break: Stop the production line and lose the ability to build ships of this size, at least temporarily.

When introducing a significant design change, providing enough time to mature the new ship design and critical subsystems before beginning construction is a lead ship best practice.Avoiding production breaks requires complementary acquisition strategies that continue to construct the existing ship class for a number of years to maintain stable workload and supplier orders while designing and transitioning to the new ship.

Conclusion

As has been the case historically, if a shipbuilding production line is abruptly stopped without a clear transition plan, there are consequences. Our shipbuilders are businesses with legal and financial responsibilities. Two of the four prime contractors are Fortune 500 companies. It should be no surprise that without orders from the Navy, production lines will be halted, workers will be laid off, suppliers will not receive task orders, and shipyards will shrink or close. This means the Navy may not be able to reconstitute a production line or reopen a shipyard if and when desired, thereby limiting the ability to build a fleet with the capability and capacity future Defense and Navy leaders will need to deter and defeat adversaries.

Accordingly, the Department of Defense’s objective should always be to transition as smoothly as possible from one shipbuilding product line to the next. Doing so requires deliberate planning with strategically-timed competitions to ensure our critical shipbuilding industrial base continues to be capable of meeting our Nation’s and Navy’s current and future needs.3 We look forward to working with all stakeholders to this end.

- “China: Naval Construction Trends vis-à-vis U.S. Navy Shipbuilding Plans, 2020-2030 [2021 Update],” Office of Naval Intelligence, March 2021, 4.

- As former Ingalls Shipbuilding President Brian Cuccias testified, “If the construction intervals get too long, it is like we are starting at square one again. For instance, the optimal production rate for LHA‐ class amphibious ships is between three and four years, depending on some variables. Presently, the program of record reflects a break in production between LHAs 8 and 9 of seven years, which would result in a cost increase of as much as $700 million above the optimal build plan. In another example, we experienced a five‐year break in production in the Arleigh Burke‐class destroyer program between DDGs 110 and 113, which resulted in a vessel labor cost increase of more than 20 percent for the first ship in the restart. These disruptions to the optimal build interval ripple through the industry down to our suppliers, many of whom are not as well situated as Ingalls [Shipbuilding] to weather the ups and downs.”

- Based on changes in the Chief of Naval Operation’s requirements, the Constellation-class frigate program is an example of a recent competitive transition from the Littoral Combat Ship to a more capable small combatant. The transition from the Flight I through Flight III Arleigh Burke-class destroyers, Block I through Block V Virginia-class submarines, and Flight I to Flight II San Antonio-class amphibious ships are examples of other deliberate Navy shipbuilding production transitions. The emerging acquisition strategy for the more capable DDG(X) destroyer program as the transition from the Flight III Arleigh Burke-class destroyer program also appears promising.