In January 2019, a video made the rounds on news and social media outlets showing a Coast Guard boarding team from the USCGC Munro (WMSL-755) interdicting a suspected drug-smuggling vessel. The highlight of this thrilling video is when the boarding officer leaps from the Munro’s small boat on to the hull of the self-propelled semisubmersible and slams the hatch in a flurry of blows, exhorting the smugglers in Spanish to “Stop your boat!” The vessel heaves to, the hatch opens, and a pair of penitent smugglers appears. All told, the boarding team recovered approximately 17,000 pounds of cocaine with an estimated value of $232 million.1

But what if, when the boarding officer knocked, no one had answered?

As autonomous vessel technology advances and transnational criminal organizations (TCOs) seek to retain their edge, the Coast Guard needs to consider the impact to one of its highest visibility missions: counternarcotics.

Drones, USVs, and UUVs

Autonomous maritime vehicles and their associated technologies are rapidly approaching initial operating capability in both commercial and military sectors. The U.S. Navy has made significant strides in this realm; its signature development is the 132-foot trimaran Sea Hunter. Building on the success of this platform and the growing technological maturity of the sphere, the Navy has initiated three programs of record to procure operational platforms of myriad sizes and capabilities:

- Large Unmanned Surface Vehicles (LUSVs); 200–300 feet overall, 21–84 inches in diameter; antisurface warfare and strike

- Medium Unmanned Surface Vehicles (MUSVs); 45–190 feet overall, 10–21 inches in diameter; intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR) and electronic warfare

- Extra-Large Unmanned Undersea Vehicles (XLUUVs); nearly 51 feet overall, diameter greater than 84 inches2

In addition, in December 2019, U.S. Fleet Forces Command directed the Surface Development Squadron—the experimental squadron tasked with exploring and integrating the capabilities of these platforms—with developing a concept of operations for the LUSV and MUSV platforms.3 In no uncertain terms, the future of the Navy is autonomous.

Not surprisingly, industry already has reached commercial viability with these technologies, and numerous companies have brought products to market. Rolls-Royce has developed and fielded a completely autonomous ferry concept.4 Hong Kong–based Ocean Alpha currently is taking orders for the M75, “a high-speed surveillance vessel.” The company boasts that the M75 can “autonomously team up to conduct massive scale search and rescue missions.” The “teaming” refers to a shared neural network that allows the vessels to perform their independent movements in concert. Oceana also features a 50-meter cargo ship, along with numerous smaller hydrographic surveying craft for sale.5

The list of commercial enterprises is long and geographically disparate, from Denmark to China and points in between. Without question, this powerful technology is within reach of TCOs, with their deep pockets and extensive criminal networks. This augurs ill for counterdrug enterprises, including and especially the U.S. Coast Guard.

TCOs and Autonomous Tech

The use of autonomous technology is not new to TCOs working to smuggle narcotics into the United States. Quadcopter-style drones regularly are used to transport limited quantities of cocaine, heroin, and methamphetamine across the southern border. Typically, the smuggler attaches contraband to the quadcopter and flies it across the border, where it is received by a co-conspirator for further distribution. This method of operations, while effective, has its limits. Most drones that have been intercepted fall into the ultralight category and thus have limited ranges and carrying capacities, typically around 40 miles and 5 kilograms.

More recent reporting, however, suggests TCOs have begun developing larger platforms capable of transporting 60–100 kilograms of contraband in a single trip.6 While this hardly provides the economies of scale that make a trip across the eastern Pacific so lucrative, it highlights criminal organizations’ willingness to harness new technologies to improve their bottom line. It is unlikely that TCOs have the research and development infrastructure to construct a flotilla of Sea Hunters on their own, but state actors possessing the technology could be willing to provide the technology to extragovernmental entities for the right reason and price.

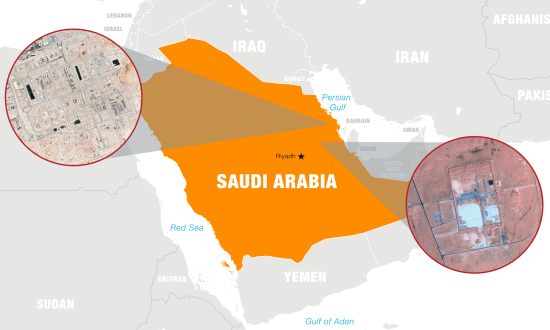

In September 2019, for example, Houthi rebels claimed responsibility for an attack on a Saudi Arabian Aramco oil refining facility that temporarily halted production of nearly 5 million barrels per day of crude oil, some 5 percent of global production.7 In a coordinated effort, 25 long-range drones and missiles targeted critical elements of the refinery facility. While numerous factors pertaining to this attack remain undetermined, evidence presented by Saudi officials indicates the drones and missiles used were of Iranian origin.8 If this is the case, this is an example of a major state power providing less-sophisticated allies with highly advanced drone technology.

It is no longer out of the question to imagine a state actor or privately held company that possesses advanced autonomous maritime vehicle technology providing that technology to TCOs.

Implementation in the Eastern Pacific

The likely end-state of autonomous technology in a smuggling capacity would be an unmanned, high-endurance platform with ample storage and characteristics that reduce the probability of detection, both above and below the water. Without the need to carry life-support systems for human operators, the platform could be designed for greater endurance, perhaps months with the correct power-generation systems. Consequently, operating range and potential smuggling routes could increase significantly, possibly beyond the current endurance limits of Coast Guard capital assets such as the national security cutter or even aerial tracking capabilities of partner Department of Homeland Security elements.

If paired with modern ISR and navigation capabilities, the platform could be able to execute comprehensive avoidance tactics, from halting passage for extended periods to allow interdiction assets to pass by, to tailing said assets just beyond detection radii. Such a platform also could facilitate a more phased, discreet narcotics logistics chain. Systems could be developed to leverage commercial trade routes, coastal fishing practices, emergent weather patterns, and even equatorial and coastal currents to create complex transportation webs.

In the near term, the uses for autonomous technology to deter interdiction on the high seas are numerous. For example, if an aerial drone launched from a mothership were of sufficient size and piloted low to the water, its radar or infrared signature could easily be interpreted as that of a small fiberglass-hulled vessel transiting at high speeds, which could trigger a watchful crew to engage in pursuit. If the drone possessed sufficient sensing capability to recognize when the interdiction asset engaged in pursuit, it could lead the vessel away from the mothership or even disable itself, leaving the pursuit crew with no indication of the target’s source.

Another crucial element of the maritime smuggling logistics chain is the refueling depot. Fishing vessels are frequently repurposed as such and staged at critical points in trafficking corridors. Operating well outside established fishing grounds, these vessels are highly suspect and obvious targets for interdiction assets, and thus they frequently are subject to boardings and search. A limited capability autonomous vehicle could easily replace these fishing boats. A large fuel tank could be equipped with sufficient propulsion and power to keep station in high seas, slightly below the waterline, and employed as an autonomous refueling depot. Developing such a system would require minimal technical capability and would add significant complexity and diffusion to existing supply chains.

Drawbacks and The Way Forward

While there is a tantalizing array of potential capabilities for TCOs to adopt, they still might find existing trafficking methods to be superior. For starters, there are cost considerations. It is hard to get any cheaper than a trio of fisherman under duress, a 22-foot fiberglass hull, a few spare outboards, and extra fuel drums. Coupled with the absurd profit margins from employing such a simple system to smuggle up to hundreds of millions of dollars in contraband, it probably is no wonder that unmanned technology has yet led to a shift in the status quo.

The higher cost of unmanned vessels also means TCOs will want them back after they make a smuggling run. If one is detected on a return trip, the interdicting crew could track where it goes and alert the host nation.

Another important consideration is the burden on interdiction assets of detaining and transporting suspected smugglers. At any given point, a substantial portion of a Coast Guard cutter’s crew could be participating in the rotating “detainee watch.” Ethical and secure care of detainees is a drain on crews, affecting crew stamina, morale, and freedom of movement throughout the ship. In addition, detainees frequently require transfer between operational assets to turn them over to Department of Justice authorities, which interrupts operational presence in known trafficking corridors. In short, in some cases, it is in a TCO’s best interest to employ human smugglers, as their presence can negatively affects a cutter’s operational performance.

The future is fraught: The rapidly approaching universality of autonomous technology could be a nightmare for the U.S. Coast Guard if it is leveraged by TCOs. In time, TCOs will encounter the juncture of lower barriers to acquisition and rising profit margins and will look to employ autonomous technology. As the United States’ premier maritime counter-smuggling organization, the Coast Guard must apply creative solutions to this problem before it reaches the TCOs.

1. “U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Munro Crew Interdicts Suspected Drug Smuggling Vessel,” DVIDS, 11 July 2019, and Morgan Gstalter, “Coast Guard Releases Video of $232 Million Cocaine Bust on Moving Submarine,” The Hill, 12 July 2019.

2. Ronald O’Rourke, Navy Large Unmanned Surface and Undersea Vehicles: Background Issues for Congress, Congressional Research Service, 23 December 2020.

3. David B. Larter, “Fleet Commander Directs U.S. Navy’s Surface Force to Develop Concepts for Unmanned Ships," Defense News, 3 January 2020.

4. Jessica Barron, “Rolls Royce’s Autonomous Ship Gives Us a Peek Into the Future of Sea Transport,” Forbes, 7 January 2019.

6. Frank Wolfe, “U.S. DEA: Border Wall or No, Drone Drug Smuggling Likely to Increase,” 10 January 2019, and Brenda Fiegel, “Narco-Drones: A New Way to Transport Drugs,” Small Wars Journal, 5 July 2017.

7. Associated Press, “Major Saudi Arabia Oil Facilities Hit by Houthi Drone Strikes,” The Guardian, 14 September 2019.

8. Natasha Turak, “Drone and Missile Debris Proves Iranian Role in Aramco Attack, Saudi Defense Ministry Claims,” CNBC, 18 September 2019.