The Coast Guard has been a seagoing service since its founding in 1790 as the Revenue Cutter Service, charged with enforcing the nation’s trade and tariff laws. Today, its cutter fleet is engaged around the globe, addressing some of the world’s toughest maritime challenges and helping to uphold a rules-based order. Unfortunately, going to sea and serving on board cutters has become the least desired job in the Coast Guard. Even command at sea has lost its luster.

Life at sea is not easy. But as the Coast Guard expands its global engagements, its cutters must be led by the highest-quality maritime professionals—and that is possible only with officer retention in the afloat community.

The service must recognize the sacrifice of those who choose this hard career path. It must understand why officers increasingly opt for shore duty and then execute the rudder corrections to ensure sea duty becomes and remains the most desired career path.

The Future Is Bright for Cuttermen, but . . .

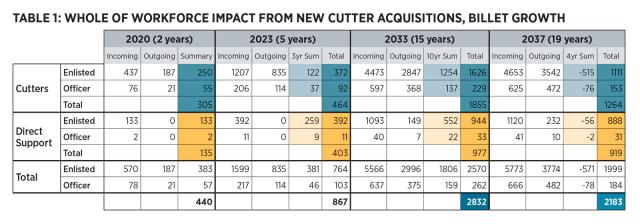

Over the next 13 years, the number of billets afloat and in direct support will increase by 25 percent, to 10,000 members. (See Table 1 on page 64.) The Coast Guard’s recapitalization effort is its largest since World War II. Polar security cutters, offshore patrol cutters, and waterway commerce cutters are forthcoming, while national security cutters and fast response cutters are still rolling off the line. As a recent ALCOAST noted, “The opportunities for seagoing members have never been greater.”1

Many cuttermen, however, do not agree. Major cutters are the least desired platforms for enlisted personnel, and the number of officers choosing the operations afloat specialty continues to shrink. In a seagoing service, members increasingly are averse to serving at sea.

The Coast Guard has reached an inflection point. If the aversion to afloat service continues, it risks deploying new ships with unwilling and inexperienced crews, unable to accomplish its statutory missions.

In a 2015 Proceedings article, Commander Brian Smicklas asked, “Cutter service is the heart and soul of the Coast Guard’s storied legacy—so why are today’s junior officers moving shoreside?”2 This shift is not affecting only the Coast Guard. In 2017, U.S. merchant mariner strength fell some 2,000 short of the Maritime Administration’s needs (11,678 versus 13,607).3 The Navy currently has 11,000 sea-duty gaps.4 The Coast Guard does not gap sea billets, but it might be forced to do so if there are no qualified and rank-appropriate applicants. Or members may be selected and directed to go afloat, even to command at sea.

The service cannot compromise on the quality of commanding officers afloat. “The need for qualified candidates has compounding impacts on mission excellence, the limitation of MISHAPs, and the success of subordinates,” a 2019 Office of Cutter Forces–sponsored report explained.5

Retention Afloat

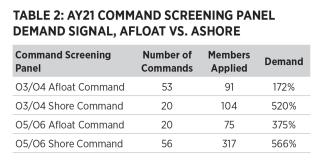

That same Cutter Forces report noted the severity of afloat officer retention: “Without action, there will be monumental challenges by 2024 in filling O3, O4, and O5 afloat billets.”6 In appropriation year (AY) 2020, the afloat detailer had to ask members to consider command, as there initially were not enough candidates at the lieutenant level. (See Table 2. All lieutenants who requested to screen for command screened successfully and were deemed fully capable of command responsibility.) The AY2021 Senior Command Afloat Panel saw a 25 percent drop in commander applicants.7

Quality commanding officers must be a service priority. The Coast Guard needs excellent commanding officers to lead the future fleet, but good leadership also helps drive retention. How, then, can the Coast Guard retain talented young cuttermen and future commanding officers? It might help, first, to examine some reasons people choose careers afloat.

Leadership Opportunities. Seasoned cuttermen carry responsibility for the safety of life at sea and accountability for their actions. Those who have commanded afloat are proven leaders, as underway professional development is second to none. The Coast Guard’s affinity for on-the-job training develops cuttermen’s ability to solve complex problems. Members formulate contingency plans, make hard decisions, execute complex missions, and take warranted risk. The skills honed in this dynamic environment carry over to other challenges, inside and outside the service.

Career Progression. Career progression is a strength in the afloat community, and with more billets coming online, it will only get better. As the Coast Guard fleet expands and integrates globally, the Commandant has called on the service to continue its “investment in ships, talent and infrastructure to operate a modernized cutter fleet.”8 In 2019, the afloat community published the inaugural Operations Afloat Officer Career Guide. It contains typical career progression tables; however, many cuttermen’s careers follow unusual paths. The “standard” career is often the exception, not the rule.

Good Pay and Bonuses. Special and incentive pays offset some of the broadly defined “costs” of sea duty.9 In 2020, sea pay was increased by $55 per month for all members afloat.10 “Increasing sea pay was a big win for the afloat community. We’re a seagoing service, and as we are growing our cutter fleet we need to ensure we recognize the value of sea service to the Coast Guard and the nation,” noted Commander Laura Moose, who cochaired the fiscal year (FY) 2021 Workforce Planning Team.11 In addition, cuttermen with dependents are eligible for a monthly $250 family separation allowance.12 There are rumblings at Coast Guard headquarters of additional sea pay increases, and even the possibility of some sort of persistent sea pay (similar to flight pay, earned even when not in an air station flight billet), but for now, these are just in the good idea stage.

In September 2020, a promising Afloat Officer Bonus program was introduced, with a $40,000 incentive to help ameliorate the lieutenant afloat crisis.13

Promotions. In promotion year 2020, cuttermen (lieutenant commander through captain with the operations afloat specialty) promoted at significantly higher percentages (22–27 percent) than non-cuttermen.14 In addition, 43 percent of all current flag officers earned their permanent cutterman’s pin, with an average of nine years’ sea time.15 That is more than any other operational specialty.

Mission. Multiple documents—including the triservice Advantage at Sea, National Security Strategy, and Coast Guard strategies related to the Western Hemisphere, Arctic, and illegal, unreported, and unregulated fishing—provide a road map for the future missions of the afloat community, clearly showing how cutters accomplish the Coast Guard’s and nation’s goals.16 These are missions of national importance, and cuttermen are vital to their achievement.

Recommendations

When the benefits of going to sea outweigh the costs for members and their families, there will be a positive correlation between sea duty and retention.17 There are several steps the Coast Guard could take toward that end:

Fund Workforce Management. The service should establish and fund a dedicated team to manage the health and growth of the afloat workforce, to make cutter assignment the most desired and rewarding career path. The Sea Duty Readiness Council (SDRC) charter was established in January 2021 but is not funded until FY2023 (~$27 million). No additional billets were created; it is a collateral duty. Finally, in April (following the normal assignment cycle, with orders already cut for lieutenants and lieutenant commanders), a solicitation for lieutenants and lieutenant commanders for SDRC positions was sent.18 These positions, one O4 and three O3s, will not bring the rank, number, or experience needed to tackle this complex problem set. In addition, as of June 2021, only one of these billets had been filled, in the Office of Cutter Forces, and it was filled by a short-term reservist.

The SDRC needs a champion—a strong captain who sees this as his or her sole responsibility for a few years, who understands the levers of power in Washington and at Coast Guard Headquarters—to make and implement the required changes. The service also must think outside the box and seek fresh viewpoints from the junior enlisted and officers who are choosing shoreside opportunities.

Collaborate. Mission-driven leaders afloat execute their tasking. However, they do it individually. As opposed to the Navy, the Coast Guard does not steam in company. There is no teamwork required outside the lifelines of the ship. The afloat community must unite to solve these problems together. It needs to rid itself of the “lone wolf” mentality and become a pack.

Every year the major cutter commanding officers come together, confer, and provide their major challenges, opportunities, and recommendations to the operational commanders. Year over year the after-action report advocates for change in how they “schedule, assign and compensate personnel, train, equip, maintain, operate, and support our cutters and crew.”19 Then the conference ends, and the commanding officers return to their cutters, hoping the problems will be solved. Cutter commanders must hold themselves accountable for the failure to solve their problems. They must follow up, and be the doers they are, as a united front, as a cutterman collective.

Communicate. The Coast Guard is a seagoing service, and it must emphasize this internally, at all accession sources and all units. It must highlight the adventure, professional advantages, missions of national importance, and service history through a robust communication plan, spearheaded by the Offices of Public Affairs and Cutter Forces. It should further promulgate “Eight Bells,” an initiative highlighting the importance of sea service to the Coast Guard.20 It also could temporarily assign more public affairs specialists on board cutters to highlight the camaraderie and experiences gained only when afloat and create motivating videos.21 The cutter community must ensure sea service traditions are continued and that the time-honored reputation and professionalism of the Coast Guard as a seagoing organization steeped in ceremony, customs, and courtesies are maintained.22

Lessen In-Port Workload. A RAND study on balancing quality of life with mission requirements on major cutters concluded working conditions matter.23 Work-life balance matters. Unpredictable (and extended) deployment schedules, long in-port work hours, away-from-homeport dry docks, attendance at C-schools during in-port periods, and extra duties all play an adverse role in members’ quality of life. Optimally manning the newest cutter classes creates more work for service members while in port. This issue rose to the top of the list of concerns at the Major Cutter Commanding Officer Conference: “In-port periods are now more arduous due to increased maintenance requirements, administrative burdens, and qualification and currency requirements.”24

The Coast Guard needs to define and separate O- versus D-level maintenance: what needs to be done by ships’ force and what needs to be done at the depot level. What if it employed the aviation model of separating operators from maintainers? Operational commanders and mission support teams must overhaul in-port schedules, consolidate training and inspections, and give time back to the crew.

For FY2022, the Coast Guard allocated $60.3 million to surface fleet readiness to “provide additional shore-side support personnel and funding to improve vessel readiness and reduce lost patrol days . . . due to deferred maintenance, reduced dry dock and dockside availabilities, and rising costs for parts and services.”25 While the presidential budget is not yet enacted, this is a win that has been driven by the Commandant and other senior leaders.

Increase Incentives. Responsibility pay (currently $50–$100 for commanding officers, yet significantly more for officers in charge) must be increased to account for the burden of command. The Coast Guard must continue to increase incentives, specifically sea pay. Sea pay should be persistent, similar to flight pay in the aviation community. While members are on shore assignment, sea pay could be held and accrue and then paid out to officers on acceptance of their next afloat tour orders (with a seven-year maximum hold). The recent $55 sea pay raise was a step in the right direction, but it did not even cover inflation since the last increase.

Financial incentives are critical, but just throwing money at the problem will not solve it. Additional incentives are needed. For example, higher assignment priority should be given on leaving major cutter assignments. Increasing geographic stability would help as well, as tours on board cutters are the shortest of any specialty, and constantly moving is an additional stressor.

Promote Afloat Officers. Command at sea—and sea duty in general—is not equivalent to a shoreside department head tour. It is more demanding and has significantly greater risk, to both life and career. Currently, the Commandant’s Guide to Boards and Panels reads:

Selection boards and panels shall remain mindful that our organization also vests broad authority and responsibility in positions that are not titled as “Commander or Commanding Officer,” positions that carry a high level of risk and accountability. Other positions also require a high degree of professional skill.26

Given that a Coast Guardsman ashore can be promoted at the same pace as a service member of the same rank who has gone to sea, it is no wonder sea duty is becoming less appealing. The final sentences of that guidance to boards and panels should read:

Other positions also require a high degree of professional skill, but none as much as the Commanding Officer afloat. None have the same level of responsibility and very few assume the same level of risk as a Commanding Officer.

The Coast Guard must recognize and promote afloat officers who take the risk and responsibility of assuming command.

Guarantee Advanced Education. The Coast Guard should guarantee graduate school to service members following a successful lieutenant afloat assignment. Some cuttermen have had back-to-back-to-back afloat assignments to fill “needs of the service.” They have a solid afloat operational specialty but no time to earn a secondary specialty before the lieutenant commander selection board. Graduate school is essential to earn their secondary career specialty and remain competitive for continued promotion. The Coast Guard should reward them with vital advanced education opportunities.

Improve Connectivity. The fleet is burdened with administrative issues that cannot be completed underway because of poor connectivity and consequently take up valuable in-port time.27 With improved internet service, members could be more connected, use earned educational benefits, and conduct necessary administrative work using web-based apps. Not being able to interact on social media with reliable bandwidth can be a deterrent to sea assignment.

On the upside, next-generation cutter underway connectivity was allotted $15 million in the FY2021 Coast Guard appropriation.28 An in-port away-from-homeport wi-fi package also was piloted to the fleet. The SDRC is working on numerous solutions to this problem.

A Rewarding Experience

A career at sea is incredibly satisfying. Going to sea has been the most rewarding experience of my career. I have seen the world, intercepted drug smugglers, ensured the health of fish stocks in the Bering Sea, and facilitated the resupply of McMurdo Station in Antarctica on the nation’s only heavy icebreaker. The relationships forged on the high seas while standing double four-to-eights, sitting on a cockroach-infested “fishing boat” waiting for authority to disembark in the eastern Pacific, navigating through williwaws and Tehuantepecers, witnessing the vastness of the oceans, and hearing your children tell their friends about Mama’s “big red ship” is what being a cutterman is all about. I hope the next generation recognizes this amazing opportunity.

Sea stories cannot be created behind a desk.

1. ALCOAST 016/21 – JAN 2021, “Sea-Duty Readiness,” 13 January 2021.

2. LCDR Brian Smicklas, USCG, “The Demise of the Cutterman,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 141, no. 8 (August 2015). See also LCDR Nicholas Monacelli, USCG, “Demise of the Cutterman Part II,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 5 (May 2021), and CDR Craig H. Allen Jr., USCG, “Still Wanna Do It?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 147, no. 8 (August 2021).

3. U.S. Maritime Administration, Maritime Workforce Working Group Report (29 September 2017).

4. Steven W. Belcher et al., Improving Enlisted Fleet Manning (Arlington, VA: CNA, July 2014). Vice Admiral Roy Kitchener, commander of Naval Surface Forces, said Navy gaps at sea would decrease to approximately 7,500 because of deliberate intervention strategies and improved use of the fit-fill method. See Megan Eckstein, “SWO Boss: Pilot Programs for Training, Manning Will Lead to More Experienced Fleet,” USNI News, 14 January 2021.

5. P. Ledbetter et al., U.S. Coast Guard Office of Cutter Forces, “Afloat Officer Corps SITREP: Analysis & Survey,” 20 February 2020.

6. Ledbetter et al., “Afloat Officer Corps SITREP: Analysis & Survey.”

7. ALCGPSC 099/20 – AY21, “Senior Command Screening Panel (SCSP) Results,” 28 August 2020.

8. Department of the Navy, Advantage at Sea (Washington, DC: December 2020).

9. Jennie Wenger et al., Balancing Quality of Life with Mission Requirements: An Analysis of Personnel Tempo on U.S. Coast Guard Major Cutters (Homeland Security Operational Analysis Center operated by the RAND Corporation, 2019).

10. Coast Guard Career 2021 Sea Pay tables, www.dcms.uscg.mil/ppc/mas/csp/.

11. Christie St. Clair, “Coast Guard Approves New Initiatives to Recruit and Retain Members,” MyCG, 12 September 2020.

12. Coast Guard Pay and Personnel Center, “Incentives, Entitlements, and Benefits.”

13. ACN 105/20 – SEP 2020, “FY21 Workforce Planning Team Results – Afloat Officer Interventions,” 10 September 2020. The incentive was “critical” to the AY2021 slate, preventing Officer Personnel Management from having to force-assign members to fill department head and executive officer afloat positions. A subsequent update lowered the bonus eligibility requirements, resulting in approximately 30 lieutenant and 20 lieutenant commander applicants for the bonus. However, many of these were people who already were requesting to go afloat. See ACN 146/20 – DEC 2020 FY21, “Workforce Planning Team Results – Afloat Officer Interventions, Update One,” 14 December 2020.

14. Ledbetter et al., “Afloat Officer Corps SITREP: Analysis & Survey.”

15. 2021 Coast Guard Flag List, www.uscg.mil/Leaders/Senior-Leadership/flag/.

16. Coast Guard senior leadership key strategies and documents can be viewed at www.uscg.mil/Leadership/Senior-Leadership/Resource-Library/.

17. Wenger et al., Balancing Quality of Life with Mission Requirements.

18. ALCGOFF 036/21, “Off-Season LCDR & LT Solicitation for SDRC Positions,” 1 April 2021.

19. “After Action Report – Major Cutter Commanding Officer Conference, 2020.

20. ALCOAST 364/20 – SEP 2020, “Eight Bells—A Sea Service Celebration on 18 October 2020,” 25 September 2020.

21. For example, see Pacific Area’s “Master Cutterman: Honoring BOSN Colton,” 3 July 2020.

22. U.S. Coast Guard, Cutter Recognition and Heritage Programs (Washington, DC: October 2019).

23. Wenger et al., Balancing Quality of Life with Mission Requirements.

24. 2020 Major Commanding Officers Conference After Action Report.

25. Coast Guard Posture Statement and FY22 Budget Overview.

26. Commandant’s Guidance to PY20 Officer Selection Boards and Panels, 23 August 2019.

27. CDR Craig Allen Jr., USCG, “Connectivity Maketh the Cutter,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 8 (August 2019).

28. Department of Homeland Security Appropriations Act, 2021 Coast Guard Operations and Support.