The world is changing fast, and so are U.S. adversaries, particularly Russia and China. According to Christian Brose, a former staff director of the Senate Armed Services Committee, this has led to an emerging need for new thinking and a “reimagination of ends, ways, and means.”1 Every U.S. partner needs to reassess its role, and the United States must ensure its partners are capable of operating in the growing antiaccess/area-denial threat environment—including in support of a littoral campaign in the High North.

The United States does not have a large and capable stand-in force in Europe, although there are plans and prepositioned forces to support one. The problem is they could be late in arriving, delayed by the Russian submarine and long-range missile threat.

The answer to this problem could be a closer relationship with already trustworthy nations. Norway has an optimal geographic position and provides NATO with access and knowledge about the operational environment, which is imperative in developing the expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) concept in the High North. The United States should consider Norway, with its expertise in winter warfare and access to the area, as a stand-in force, prepared and postured to support a littoral campaign in the High North. This will require interoperability in concept, technology, and warfighting culture.2

Concept. There can be no effective course of action until allies are integrated into concept development. New ideas such as EABO are emerging, but there is little understanding of how the U.S. joint force is going to prepare and posture itself to deter and fight a near-peer adversary in the High North.3 As of now, allies such as Norway do not have a major role in the development of a concept that will require access to their territory.4

Technology. Another concern is building interoperability within the technology domain—specifically, how the Norwegian Armed Forces (NAF) could tie into the U.S. kill chain to ensure efficiency in prosecuting targets of interest. Key partners should be included early in the discussion on implementing and exploiting new technology.

With the emergence of longer-range weapons, the character of war may be changing—and with it, a change in the requirement for allied reinforcements. Indeed, where this previously encompassed massive boots on the ground and staging equipment and units, it could in the future mean effects such as air and long-range fire support. For the Alliance, interoperable, low-signature, and secure communications will be critical.5 Interoperable technology will ensure U.S. and NAF systems complement and speak to each other, which will strengthen the allied kill chain. This will build credibility, an imperative for deterrence of a near-peer adversary.6

Warfighting Culture. To ensure success, U.S. forces and the NAF require a shared warfighting culture. The U.S. Marine Corps has a long tradition of training in Norway. Even so, during exercise Reindeer II in November 2020, the Norwegian commander, Major General Lars Lervik, expressed the need for a better “mutual understanding of what the different military terms mean, so that when an order is given, we can both act in the same way”7

Culture plays a role in an organization’s ability to understand the operational environment and the immediate situation. It has a direct effect on the organization’s or soldier’s ability to orient, to understand what is going on. Orientation—part of the observe, orient, decide, act (OODA) loop—controls how people make sense of what they observe, and it shapes their decisions and actions.8 Without a shared culture, the United States and its allies could view the same situation completely differently—which an adversary will see as a vulnerability to exploit.

A Norwegian Stand-in Force

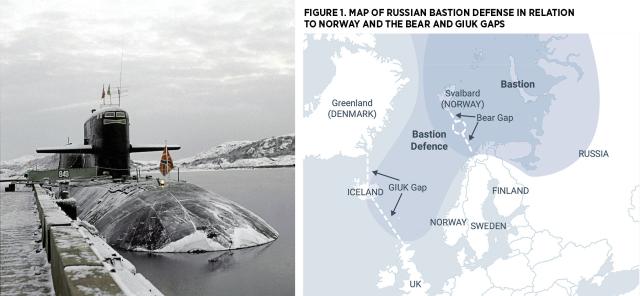

A potential solution to the Russian threat in the North Atlantic is to use the NAF as a stand-in force. For example, from their main base in Severomorsk, Russian submarines sail along the Norwegian coastline, passing between the Svalbard islands and Bear Island (the Bear Gap) before reaching the Greenland-Iceland-United Kingdom (GIUK) Gap and the deeper waters of the North Atlantic. Operating inside the Russian weapons engagement zone, the NAF would be able to detect, track, and deliver targeting data to the Alliance to deny the submarines freedom of action.

Moreover, because Russian submarines today are equipped with longer-range and better-performing cruise and ballistic missiles, they need not go south of the GIUK Gap to present a threat to NATO reinforcements arriving by ship or air. The Alliance will have to search for submarines farther north, likely in concert with the NAF, as the contested environment might deny allied forces access.9 The area connecting the Barents and Norwegian Seas is the perfect area to search for Russian submarines, and building a concept that involves NAF antisubmarine warfare forces already in the area will build credibility.

The NAF also specializes in operating in the subarctic climate and has an expert understanding of that environment, which will make it a key enabler in a littoral campaign in the High North. Integrating the NAF in concept development will enable it to connect with the U.S. OODA loop at an earlier stage and push information to its decision-makers on procuring the right technology at the right time. If the NAF does not have access to the concepts being developed, or if they are unclear, it will lack the technology needed to act as the stand-in force in a potential littoral campaign in the North Atlantic.19

More closely connecting the NAF with the U.S. kill chain would reduce the need for U.S. boots on the ground. The NAF could focus on developing its organization and ensuring every part could deliver targeting data up the chain faster and more reliably than today. Greater interoperability and early integration of allies and partners in concept development would set the stage for a more unified effort toward deterring Russia.11

An alliance also provides cognitive diversity. Different perspectives and understandings of the operational environment strengthen a team’s ability to outthink an adversary.12 However, it is essential that cultural differences do not negatively affect cooperation and efficiency. According to Leonard Wong and Stephen J. Gerras, “a culture provides the underlying foundation for decisions in strategy, planning, organization, training, and operations” and is a contributing factor for allied effectiveness.13 Consequently, if U.S. forces and the NAF wish to become more credible and lethal, they will gain an enormous advantage by establishing a shared warfighting culture. They can accomplish this by operating in a more integrated fashion and by identifying where perspectives differ—and the best way to do that is by planning, training, educating, and operating together on a regular basis. For example, there should be more student exchanges on all levels, as these provide vital knowledge about how the different organizations think and operate.The commanding officers of Marine Rotational Force–Europe and Norway’s Brigade North confer during exercise Reindeer II. Planning, training, and operating together can iron out cultural differences and increase allied cooperation and efficiency.

Mutual understanding is even more important today, as adversaries are widening the definition of conflict and war and finding new ways to reach their goals. The hybrid element in all domains makes situations harder to read, and without a unified strategic culture, there is a greater risk of confusion and missteps.

Some might argue it would be a risk for Norway to become more interwoven with U.S. forces, as it could increase tensions with Russia.14 Norway’s close relationship with one of its oldest partners is not new; however, there is an enormous difference between that and the NAF acting as a stand-in force in the North Atlantic. A closer connection with the U.S. kill chain combined with antisubmarine warfare in the Bear Gap would reduce Russian submarines’ freedom of movement. This also might force Russian leaders to find a different way of prosecuting liminal warfare.15

The Norwegian Armed Forces can be included as a stand-in force, as part of U.S. joint concepts, to support a littoral campaign in the High North. But to present a credible solution, Norway should participate in concept development, as this will support interoperability in technology and warfighting culture. In this way, Norway will present Russia with a stronger deterrent and combat capability, which supports the preservation of peace and defense of the nation.16

1. Christian Brose, The Kill Chain (New York: Hachette Book Group, Inc, 2020), 187.

2. James C. Boozer, “Allies, Partners More Important Than Ever,” National Defense, 26 May 2020.

3. Nathan Freier, John Schaus, Al Lord, Alison Goldsmith, and Elizabeth Martin, “The U.S. Is Out of Position in the Indo-Pacific Region,” Defense One, 19 July 2020.

4. Terje Bruøygard and Jørn Qviller, “Marine Corps Force Design 2030 and Implications for Allies and Partners Case Norway,” Journal of Advanced Military Studies 11, no. 2 (2020): 199.

5. Gen David H. Berger, USMC, Commandant’s Planning Guidance: 38th Commandant of the Marine Corps (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, July 2019), 20.

6. Boozer, “Allies, Partners More Important Than Ever.”

7. Christopher Woody, “Marines Training for Winter Warfare in Norway Also Have to Deal With ‘Different Military Terms,’” Business Insider, 6 December 2020.

8. Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 1-4, Competing (Washington, DC: Headquarters, U.S. Marine Corps, 14 December 2020), 4-3.

9. Thomas Nilsen, “American Flags in the Barents Sea Is ‘the New Normal,’ Says Defence Analyst,” The Barents Observer, 8 May 2020.

10. Bruøygard and Qviller, “Marine Corps Force Design 2030 and Implications for Allies and Partners Case Norway,” 198–200.

11. Boozer, “Allies, Partners More Important Than Ever.”

12. Boozer.

13. Leonard Wong and Stephen J. Gerras, “Culture and Military Organizations,” in The Culture of Military Organizations, Peter R. Mansoor and Williamson Murray, eds. (New York: Cambridge University Press, 2019), 17.

14. Norsk Telegrambyrå, “SV og Rødt vil stanse amerikanske militærbaser i Norge,” Forsvarets Forum, 6 November 2020.

15. David Kilcullen, The Dragons and the Snakes. How the Rest Learned to Fight the West (New York: Oxford Press, 2020), 115–64.

16. Kilcullen, The Dragons and the Snakes, 251–55.