For the past 20 years, the nation’s military has operated in largely uncontested environments, establishing maritime sanctuaries and air superiority with relatively few constraints. But in 2018, the National Defense Strategy (NDS) warned that the U.S. “competitive military advantage has been eroding.”1 Signed by then–Secretary of Defense James Mattis, it states that “inter-state strategic competition, not terrorism, is now the primary concern in U.S. national security.”2 In March 2021, President Joseph Biden’s Interim National Security Strategic Guidance (INSSG) reaffirmed that China and Russia have “invested heavily in efforts meant to check U.S. strengths and prevent us from defending our interests and allies around the world.”3

But the Navy’s force is strained—mentally, physically, mechanically—from the toll of continuous war. If the service is to prepare for strategic competition, maintenance and modernization programs need updating, the best enlisted sailors and officers must be retained to lead in future conflicts, and new recruits must be trained for the front lines.

The Navy cannot continue the status quo of a can-do culture that constantly appeals to a sense of patriotism and duty for short-term needs. In the event that global state-on-state conflict erupts, this approach will leave precious little energy to devote to true “operational necessity.” In its current state, the Navy will be unable to provide its historic level of security and power projection should the United States unwittingly slide straight from its longest war to its most formidable.

Short-Term Specific Actions for a Long-Term Reward

High operational tempo is the root cause of declining ship and aircraft conditions, maintenance delays, mishaps, and an overstressed and fatigued workforce. Yet operational decisions at the highest levels do not seem to reflect the situation. The Navy is planning a “larger, more

lethal future fleet” in accordance with the Chief of Naval Operations’ Navigation Plan released in January 2021.4 To effect this, operational tempo must be dialed down temporarily, while steps are taken to facilitate retention, maintenance, training, infrastructure development, and acquisition. Specifically, the Navy should:

• Restrict deployment extensions. The original Fleet Response Plan (now Optimized Fleet Response Plan) was implemented in part to allow combatant commanders the flexibility to surge and extend deployments during times of operational necessity, such as war. Deployment extensions are now almost a guarantee, often for the purpose of maintaining “heel-to-toe” presence in the Fifth and Seventh Fleet areas of responsibility.5 These strategically ambiguous and operationally predictable extensions put unjustifiable strain on ships, sailors, and families.

• Make better use of dynamic force employment (DFE). Introduced in the 2018 NDS, DFE can accomplish specific strategic goals while preserving the Navy’s assets for readiness. The USS Harry S. Truman (CVN-75) strike group successfully demonstrated the first—and last—DFE deployment in 2018, accomplishing in only a three-month deployment its mission of striking the Islamic State in the Middle East and supporting partnership exercises in Sixth Fleet.6 DFE allows the Navy to use operational unpredictability to confound adversaries in support of specific objectives.

• Refocus operational necessity. This concept is invoked to authorize a particular action in support of a mission. In response to the COVID-19 pandemic, commanders certainly tested the limits of the idea by restricting sailors from seeing their families before deployments and sometimes cutting port calls entirely. Now, while attempting to rebuild readiness, Navy leaders should look for opportunities to turn the concept around. Instead of asking what actions are necessary for an operation, the question should be, “Is this operation necessary?”

Presence operations, supposedly designed to deter unwanted action by foreign actors, should be abandoned as a strategic objective. The necessity of such operations is dubious, given the rising costs of providing constant presence around the world and the unverifiable benefits they ostensibly provide. The Navy’s operations should instead focus on prioritizing joint force integration, training for the modern fight, partner-building, and missions in support of specific actions to conclude America’s wars in the Middle East. By refocusing operations to those that provide unambiguous strategic benefits, the Navy will alleviate the burden on people and equipment in the interim, while building the readiness needed for the long term.

• Encourage leave and liberty. COVID-19 magnified the pain of operations in 2020–21, and the virus may circulate for some time to come. As quarantine requirements and travel restrictions lift, the Navy must expedite a return to normalcy. Unit-level commanders and officers should encourage leave and liberty to the maximum extent possible, even in operationally difficult situations, such as work-ups and deployments. The Navy took extraordinary measures to restrict personal travel, prohibit port calls, and quarantine sailors for the sake of operational readiness; now it is time to prioritize mental and emotional health for a loyal and exhausted force.

Admiral Phil Davidson articulated the Navy’s ethos in the 2017 Comprehensive Review of Surface Forces: “A can-do culture, when self-inspired, is a virtue that the Navy relies on to be successful. The can-do culture becomes a barrier to success only when directed from the top down or when feedback is limited or missed.”7 Today, a can-do culture from the top of the chain of command is straining the forces, eroding trust among subordinates while weakening the power of a call to arms.

The Navy’s Physical Assets Are Not Ready

Ships, submarines, planes, and infrastructure are run ragged from decades of overuse. Maintenance backlogs drag down readiness in every warfare community, and the infrastructure in place to fix them has long been neglected. Meanwhile, sailors, Marines, officers, chiefs, aviators, submariners, and civilians have been working hard to protect U.S. security interests around the world. A high operational tempo and manning shortages have plagued the fleet, which has loaded more work on those who remain—leading to more maintenance delays, mishaps, and avoidable deaths. These challenges must be addressed in the short term, because fleet and infrastructure modernization, as well as personnel buildup, will take decades to accomplish.

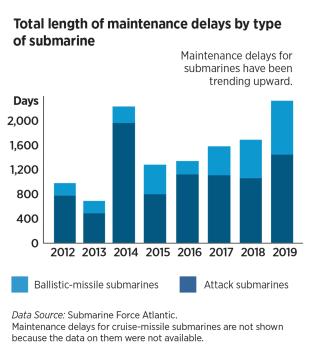

A Government Accountability Office (GAO) report showed that the Navy experienced 28,238 days of maintenance delays from fiscal year (FY) 2014 to FY2020 for all surface ships except aircraft carriers.8 That equates to 77 years of delays in just seven calendar years. The Congressional Budget Office analyzed the submarine community, which has logged nearly 10,000 days of maintenance delays since 2012.9 Increased deployment lengths and maintenance availability backlogs have led to declining ship conditions and swelling maintenance requirements.

From 2011 to 2019, only 2 of the Navy’s and Marine Corps’ 19 aviation platforms—the EP-3 Aries and E-6B Mercury—met their annual fully mission capable (FMC) goals more than 50 percent of the time. Fourteen of the platforms never met their FMC goals during that period. According to GAO, the Navy reports that “the pace of operations has increased wear and tear on its aircraft and decreased the time available for maintenance and modernization.” The well-publicized delays of the F-35B/C program forced the Navy and Marine Corps to rely more heavily on older platforms such as the F/A-18 Hornet and AV-8B Harrier for much longer than planned.10

Maintenance backlogs across the fleet are exacerbated by ports, bases, and repair depots that are out of date vis-à-vis modern standards, overtasked with extra repair requirements, and under-resourced with manning and equipment. Public and private shipyards struggle to complete maintenance on time, and insufficient dry dock capability is projected to result in roughly 30 percent of maintenance availabilities going unsupported through 2040. GAO reports that two of the Navy’s three fleet readiness centers (FRCs), which work on depot-level repair for aircraft, are in poor condition.11 Twenty years of budget prioritization to support operations in the Middle East have enabled the neglect of facilities and infrastructure.

Personnel Are Exhausted

The INSSG states that “first and foremost, we will continue to invest in the people who serve in our all-volunteer force and their families.”12 The Navy needs its best and brightest at the forefront of strategic decision-making, logistical planning, and tactical operations. Yet high operational tempo combined with a cumbersome personnel management bureaucracy has resulted in insufficient personnel for units and the departure of much of the Navy’s top talent.

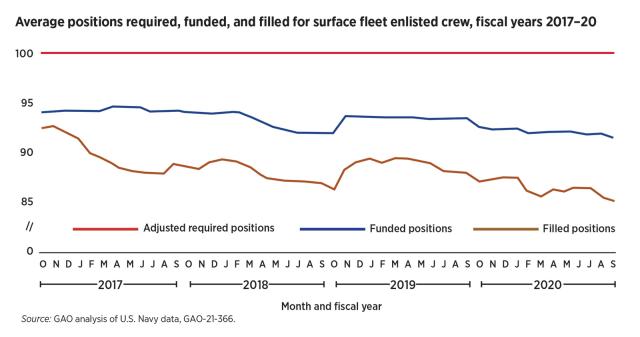

In December 2020, then–Fleet Master Chief Rick O’Rawe said of the number of unfilled enlisted billets: “For our operational fleet units, today, we’re over 10,000 [manning] gaps at sea.”13 The Navy has consistently not funded enough billets on ships compared to what is required, and has failed to fill even the funded billets.14 A 2003–12 cost-savings measure, “optimal manning,” has further aggravated the situation. In 2017, GAO reported that “reduced crew sizes resulted in minor maintenance being deferred, which led to more costly issues that had to be addressed later at the depot level.”15 Chronically undermanned units leave their personnel with increased fatigue and stress, which can lead to decreased productivity, mishaps, alcohol-related incidents, mental health issues, even suicides.

Naval aviation has suffered from undermanned squadrons exacerbated by bottlenecked training periods, retention troubles, and the high operational tempo of aircraft carriers. A shortage of trained maintenance personnel was cited as a cause for sustainment challenges affecting 15 of the Navy’s 19 aviation platforms.16 The strike-fighter (VFA) community in particular has been plagued by readiness challenges that slashed F/A-18 aircrew production to below 50 percent for both FY2018 and FY2019, a full year of aviator production lost.17 Efforts in 2020 to mitigate more than 180 gapped VFA billets mostly came in the form of extending operational tours or cutting shore tours early to fill fleet requirements. This only intensifies the stress of those who stay in.

In the Comprehensive Review, which analyzed the causes of the tragic mishaps of the USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) and USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62), Admiral Davidson included the increased operational tempo of Seventh Fleet ships and subsequent decline in training.18 Then–Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral John Richardson shed light on the harmful consequences of the pressure-cooker approach: “Over a sustained period of time, rising pressure to meet operational demands led those in command to rationalize declining standards, standards in fundamental seamanship and watchstanding skills, teamwork, operational safety, assessment and a professional culture. This resulted in a reduction of operational safety margins.”19

Calls for addressing retention are increasing. In 2020, former Commander, U.S. Submarine Forces, Vice Admiral Daryl Caudle asked all submarine commanders to prioritize the problem.20 Congress has highlighted aviation retention issues, and the Navy’s COVID-19–related retention gains will likely be temporary unless work-life balance is addressed.

Every warfare community is shooting red flares about declining morale and increased stress. The welfare of the Navy’s forces is suffering to a point of crisis. For the service to be prepared for strategic competition against powerful nations, it must prioritize the morale, training, and efficiency of its people, in accordance with the INSSG.

Long-View Solutions

Solutions are in the works. The Navy is implementing programs to rebuild personnel, machinery, and infrastructure. The Shipyard Infrastructure Optimization Program takes on inefficiencies in shipyard layouts that could save up to 328,000 labor hours per year, but will take 20 years to implement.21 The Shipyard Performance to Plan Initiative, started in 2018, relies on a data-driven approach to solve workforce problems that contribute to delays in maintenance periods. The plan is still in incipient phases, with key metrics remaining underdeveloped.22 Other modernization programs aim to reduce the average age of equipment and facilities to within industry standards; these measures will take an estimated 30 years to accomplish.23

On the manning side, there have been numerous efforts to revamp Navy personnel policy, most under the umbrella of the Sailor 2025 program. A renewed focus on talent management, career flexibility, continuing education, and modern training programs is intended to reorient the Navy to compete with the dynamic and innovative private sector. In response to the Comprehensive Review, the service increased manning requirements across all ship classes to mitigate future mishaps. However, increasing requirements does not guarantee that bodies can be placed where they are needed. The Navy has not yet been able to provide the needed manpower, because recruiting efforts, accession processes, and training pipelines require a significant time investment before individual commands can reap the benefits.24

The Bottom Line

The Navy must face reality and stop trying to do more with less. With wars in the Middle East ending and budgetary constraints continuing to tighten, the service needs an interim period to adjust course. Operations cannot halt completely, but a lower operational tempo more in line with the current strategic landscape will allow the Navy to reestablish a wartime readiness posture in the future, should it be needed. Demanding less of physical assets now will reduce unscheduled maintenance actions, thereby improving longevity and reliability. And if sailors and their families feel that their morale and welfare have been prioritized today, in the future they will be more willing to sacrifice. These actions should be considered an investment in the future force, one that will yield returns as beneficial as a major personnel initiative or shipyard infrastructure program.

The future of maritime security, gray-zone conflict, and the potential for war against modern, near-peer adversaries demand that the Navy seek realistic solutions within constraints, not despite them. This will require buy-in from upper-echelon decision-makers in the Office of the Secretary of Defense, National Security Council, and combatant commands. Leaders at all levels should advocate for the welfare of their forces and assets, speaking up when the cost of operations outweighs the benefits.

1. James Mattis, 2018 National Defense Strategy, Department of Defense, 19 January 2018, 1.

2. Mattis, 2018 National Defense Strategy.

3. The White House, Interim National Security Strategic Guidance, briefing, 3 March 2021.

4. U.S. Navy, “CNO Releases Navigation Plan 2021,” press release, 11 January 2021.

5. Megan Eckstein, “No Margin Left: Overworked Carrier Force Struggles to Maintain Deployments,” USNI News, 12 November 2020.

6. David B. Larter, “Jim Mattis’ ‘Dynamic Force Employment’ Concept Just Got Real for the U.S. Navy,” Defense News, 16 July 2018.

7. ADM Philip Davidson, USN, Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents, U.S. Fleet Forces Command (26 October 2017), 19.

8. Diana Maurer, Navy and Marine Corps Services Continue Efforts to Rebuild Readiness, but Recovery Will Take Years and Sustained Management Attention, GAO-21-225T (2 December 2020), 5.

9. Congressional Budget Office, The Capacity of the Navy’s Shipyards to Maintain Its Submarines, report (25 March 2021).

10. Maurer, Efforts to Rebuild Readiness, 21–23.

11. GAO, Military Depots: Actions Needed to Improve Poor Conditions of Facilities and Equipment That Affect Maintenance Timeliness and Efficiency, GAO-19-242 (29 April 2019).

12. The White House, INSSG briefing.

13. Rick O’Rawe and John Cordle, “Manning Still Matters: A Fleet Perspective,” Proceedings Podcast Episode 197 (U.S. Naval Institute, 2 December 2020).

14. GAO, Navy Readiness: Additional Efforts Are Needed to Manage Fatigue, Reduce Crewing Shortfalls, and Implement Training, GAO-21-366 (27 May 2021).

15. GAO, Navy Force Structure: Actions Needed to Ensure Proper Size and Composition of Ship Crews, GAO-17-413 (18 May 2017). Maurer, Efforts to Rebuild Readiness, 16.

16. Maurer, Efforts to Rebuild Readiness, 24.

17. CAPT Forrest Young, USN, PERS-43, update at Virtual Tailhook ’20 Conference, 12 September 2020.

18. Davidson, Comprehensive Review.

19. U.S. Department of Defense, “Department of Defense Press Briefing by Adm. Richardson on Results of the Fleet Comprehensive Review and Investigations into the Collisions Involving USS Fitzgerald and USS John S. McCain,” transcript, 2 November 2017.

20. VADM Daryl Caudle, USN, “Sustaining the Submarine Force’s Competitive Edge,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 146 no. 10 (1 October 2020).

21. Maurer, Efforts to Rebuild Readiness, 13.

22. GAO, Navy Shipyards: Actions Needed to Address the Main Factors Causing Maintenance Delays for Aircraft Carriers and Submarines, GAO-20-588 (20 August 2020).

23. Maurer, Efforts to Rebuild Readiness, 13.

24. Maurer, 17.