When former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson issued A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority Version 2.0 in December 2018, he highlighted the growing threat to freedom of navigation for the U.S. Navy: “Our competitors have been studying our methods over the past 20 years. In many cases, they are gaining a competitive advantage and exploiting our vulnerabilities.”1 Sea power requires unconstrained access to the oceans, waterways, and littorals, and potential adversaries understand the importance of sea lanes to preserving U.S. security interests. A single sea mine—confirmed, suspected, or even just threatened—could bring operational plans “to a grinding halt.”2

Russia, China, Iran, and North Korea all maintain robust and sophisticated mine inventories numbering in the tens to hundreds of thousands.3 To prepare for potential large-scale mine warfare in great power competition, the Navy must assess current and developing mine countermeasures (MCM) systems, force structure, and strategy to determine if its capabilities will be adequate to mitigate the threat. It cannot underestimate the potentially devastating cost of the low-end threat in the high-end fight.

The Vicious Mine Warfare Cycle

Department of Defense (DoD) interest in MCM follows what has been called “the vicious mine warfare cycle.”4 It starts with a mine attack, followed by the rise of MCM to the forefront of strategic discussion as conflict continues. Post-conflict, DoD budgets decline and MCM must compete for funding against more sophisticated and expensive technological threats. Interest in MCM fades, with little changes to the nation’s ability to confront an ever-evolving mine problem. The danger, however, endures.

In 2018, China’s People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) conducted “one of the largest mine warfare exercises in history.”5 Sixty minelayers, minesweepers, aircraft, and submarines practiced laying and countering live mines, while China’s top scientists and mine-development specialists evaluated the operations.6 China maintains 17 classes of ships, 10 classes of submarines, and two types of aircraft with the capability to deploy mines.7 A 2009 U.S. Naval War College study suggests China possesses more than 100,000 sea mines “and that their use [is] fundamental to its strategy in constraining U.S. Naval Forces operating in Beijing’s area of interest.”8

A 2006 edition of the Chinese doctrinal textbook Science of Campaign instructs the PLAN to develop warfare systems that “can force their way into enemy ports and shipping lanes to carry out minelaying on a grand scale.”In the August 2015 Chinese naval magazine Modern Ships, a study from China’s National Defense University envisions responding to a Taiwan declaration of independence with a mine blockade. The first phase would involve 5,000–7,000 mines deployed over four to six days. The second phase would involve laying an additional 7,000 mines.9

A Chinese analyst commented on the U.S. Navy’s ability to sortie in response to such mine-laying action: “The U.S. will need to move supplies by sea. But China is not Iraq. China has advanced sea mines . . . it took over half a year to sweep all Iraq’s sea mines. Therefore, it would not be easy for the U.S. military to sweep all the mines that PLAN might lay.”10 The analyst understood the U.S. Navy’s history of independently operating, autonomous MCM units ill-suited to counter grand-scale mine warfare.

A Legacy of Mine Warfare

The Department of the Navy’s legacy MCM systems include Avenger-class ships providing surface MCM, MH-53E Sea Dragon helicopters executing airborne MCM, and explosive ordnance disposal (EOD) mobile units conducting expeditionary MCM. These three communities employ “specialized ships, personnel, and systems . . . [operating] as a force separate and apart from the larger Navy” and, historically, not reliant on one another.11

(LT Robert Swain)

The Navy christened the USS Avenger (MCM-1) in 1987. Outfitted with sonar and video systems, cable cutters, and mine detonation devices, these ships can find, classify, and destroy moored and bottom mines. Between 1987 and the late 1990s, the Navy commissioned 14 Avenger-class ships and 12 Osprey-class coastal minehunters. However, in a recent report to Congress, the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations outlines the Navy’s intent to “accelerate retirement of mine countermeasures ships.”12 In August 2020, it retired the final three stateside-based Avengers. The goal is to harvest no longer manufactured ship and mission system parts to improve forward-deployed MCM operational availability.13

Helicopter mine countermeasures (HM) squadrons have operated in the Navy since the 1970s, providing full spectrum detect-to-engage MCM.14 The sundown of the MH-53E is set for fiscal year 2025.

A 2012 joint urgent operational need statement for increased MCM capability in the Central Command (CentCom) area of responsibility led to the establishment of an expeditionary MCM company out of EOD Mobile Unit 1 (EODMU-1).15 By coupling the Mk 18 Mod 1 Swordfish and Mod 2 Kingfish unmanned underwater vehicles (UUVs) with traditional EOD dive platoons, the company delivered complete expeditionary detect-to-engage MCM to the CentCom combatant commander. A separate five-person cell analyzes sonar and video data captured by the Mk 18 and makes recommendations to higher mine warfare headquarters. Today, eight expeditionary MCM platoons support operations in CentCom, and EOD expects to double the number of unmanned systems platoons over the next three years to support Indo-Pacific Command as well.16

Surface, airborne, and expeditionary mine countermeasures form the MCM triad, but while combined efforts have occurred, the three rarely integrated to clear a minefield. After almost 30 years of operating independently and autonomously, in 2013 HM helicopters and MCM ships performed the first forward-deployed integrated exercise in Fifth Fleet.17 Most recently, in September 2020, a Mk 18 platoon operated with the USS Dextrous (MCM-13) to test integration during a surface MCM scheme of maneuver, and in November 2021, a Mk 18 platoon integrated with Helicopter Sea Combat Squadron 21 (HSC-21) to refine tactics for expeditionary MCM systems employment from MH-60S helicopters.

A System of Systems

Today, the Navy is beginning to employ a new model for MCM. The manned–unmanned team includes littoral combat ships (LCSs) operating with expeditionary MCM platoons equipped with UUVs and the HSC community’s manned MH-60S Knighthawk and unmanned MQ-8B Fire Scout. This modular, tailorable MCM force structure has the potential to enable broad-spectrum sea control. Unfortunately, the individual organizations accountable for parts of the composite LCS MCM mission package are preparing “man, train, equip” readiness for their systems and personnel independently. In great power competition, an MCM system of systems depends on synchronizing the efforts of these disparate organizations.

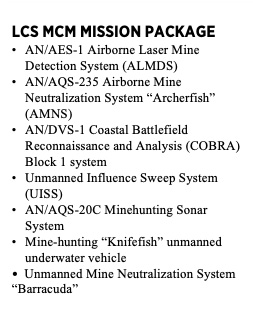

The LCS MCM mission package advertises seven mine detection, neutralization, reconnaissance, minesweeping, and minehunting systems working together to provide tailored MCM based on the threat.18 Almost 20 years after its inception, however, the MCM mission package has yet to deploy as a functional composite force. The first partial mission-capable MCM LCS deployed to Seventh Fleet in February 2021.19 The ship embarked an aviation detachment (AvDet) comprising one MH-60S, one MQ-8B, four pilots, four aviation warfare specialist sensor operators, and a maintenance footprint dual-qualified in MH-60S and MQ-8B airborne MCM systems. The detachment provides three of the seven LCS MCM systems with (disputed) initial operational capability clearances; the remaining four are still in testing.20 Personnel assigned to handle the equipment are few in number and limited in experience.

Without the remaining MCM systems, the AvDet offers only limited MCM capability to geographic combatant commanders.

Expectation Management

The single MH-60S and MQ-8B embarked on LCS provide less than half of the advertised MCM systems capability for full water column mine detect-to-engage; yet, in 2021, they provide the only LCS MCM capability to the Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet. HSC outfits the LCS MCM mission package with the capability to detect near-surface mines, but not the ability to classify them with the AN/AES-1 Airborne Laser Mine Detection System (ALMDS). They provide neutralization of bottom or moored mines with the AN/AQS-235 Airborne Mine Neutralization System “Archerfish,” but only those mines identified by an off-board mine-detection system. Archerfish works in a different section of the water column than ALMDS, and, therefore, the MH-60S cannot prosecute the mine-like contacts it locates. The final system with initial operational capability clearance, the AN/DVS-1 Coastal Battlefield Reconnaissance and Analysis (COBRA), is advertised to detect coastal or beached mines, but the AvDet is not equipped to neutralize these hazards through complete detect-to-engage.

The four pilots assigned to fly the MH-60S also function as air vehicle operators for the MQ-8B. Unlike the expeditionary MCM model, which does not require Mk 18 operators to be highly specialized EOD techs, HSC cannot embark separate unmanned operators to assist the specialized rotary-wing aircrew because of limited LCS berthing.21 This constraint, driving a minimally manned AvDet, will inevitably reduce the MCM operational availability that combatant commanders expect.

The same manning limitations force aircrewmen to function as both mission payload operators for the MQ-8B and sensor operators in the MH-60S. In addition to dual hatting as manned and unmanned operators, these individuals also conduct ALMDS and Archerfish post-mission analysis. Even though the system advertises a one-hour analysis for every hour of search capability, sensor operator feedback indicates they conduct up to two hours of analysis for every hour of flight time.22 The ALMDS’s inability to automatically identify, process, and classify mine-like contacts, and the resulting tedium of post-mission analysis, strains flying crews’ operational tempo and operational availability. Neither expeditionary MCM nor legacy airborne MCM requires the same individuals who execute the MCM mission to conduct follow-on analysis. Tasking the AvDet with such post-mission analysis will preclude an independently operating LCS AvDet from conducting the long-term MCM campaigns necessary to counter near-peer adversary mining operations.

Measures of Effectiveness

The current LCS construct complicates MCM execution. Without asset redundancy, routine maintenance port calls, underway supply chains, and parts availability become crucial to sustained manned and unmanned operations. Combatant commanders will need to understand the paradigm shift from Avenger-class ships and MH-53E detachments, capable of extended autonomous operations, to the limited flight windows and maintenance periods of the LCS MCM mission package.

Legacy MCM assets operate independently of carrier strike group and amphibious ready group operations. This is no longer possible. While these specialized units safeguard expertise and experience unique to their MCM community, adversary mine capability threatens all surface vessel plans for distributed maritime operations. The Navy expects to decommission the Avenger-class ships and sundown the MH-53E by 2027.

In HSC, only 2 of 16 operational squadrons train to airborne MCM, and LCS maintains no executable plan for the four remaining surface-employed MCM systems that will integrate onto the ship—or a date for achieving IOC. Without those plans, surface and aviation leaders are compelled to establish infrastructure for an integrated transition plan that captures the experience and trade knowledge of legacy MCM units and transfers it to the novel organizations developing MCM tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs). TTP development will continue unsynchronized, inefficient, and potentially operationally unrealistic until all systems contributing to the LCS MCM mission package function to the requisite operational capacity.

Charting the Course Forward

Seasoned MCM capability is developing a void. Minemen are being detailed to LCS MCM mission package ships without equipment to train with or operate. This takes billets from the Avenger-class ships and HM squadrons and can leave the Navy with atrophying skills and an irreversible loss of corporate MCM knowledge.23 Navy leaders should heed the warnings in the 2003 U.S. Naval Mine Warfare Strategy: Analysis of the Way Ahead. The report cautions:

LCS is central to the Navy’s vision of transforming the MCM force, should the LCS vision fall short in the long run due to technological or force integration problems, then the risk increases. Should this occur, and developmental costs spiral upward, the Navy should guard against allowing current MCM capabilities and readiness to atrophy at the expense of the LCS and organic systems development.24

The following are options for the Navy to consider while preparing a force with the capacity, technology, and synchronized TTPs to counter large-scale adversary mining:

Establish additional airborne MCM-qualified squadrons in Norfolk, San Diego, and within the forward-deployed naval force to distribute the burden of handling future airborne MCM operations, supporting LCS MCM mission packages—currently carried solely by HSC-21 of HSC Wing Pacific and HSC-28 of HSC Wing Atlantic. Adversary mining will demand a rapid response from multiple MCM-qualified AvDets after legacy systems decommission.

Integrate command and control for LCS with an amphibious ready group, carrier strike group, or expeditionary sea base through the Optimized Fleet Response Plan and while deployed. These larger force packages can provide logistics, force protection, and maintenance support while mitigating LCS MCM mission package logistical limitations—only one helicopter configured for airborne MCM operations that is unable to easily support other air logistics requirements and ship missions.

Fund additional testing for vessels of opportunity (VOO) to support the MCM mission package and expeditionary MCM assets. In 2020, the USS Hershel “Woody” Williams (ESB-4) demonstrated successful MCM mission package integration by embarking HSC-28, USV systems, and Knifefish. Follow on testing during exercises such as Rim of the Pacific or Baltic Operations will validate the manpower, training, and performance requirements for codified VOO concepts of operation and readiness matrices. The infrastructure could extend to L-class ships, foreign vessels, and Military Sealift Command ships with continued proof of concept testing.

Combine the training pipeline at the Mine Warfare Training Center in Point Loma, California, for LCS billeted minemen and HSC aircrew to conduct MH-60S ALMDS and Archerfish post-mission analysis. This will strengthen the relationship between LCS and HSC personnel, standardize training, and extend the operational availability of MH-60S aircrew to fly longer MCM missions.

Advise combatant commanders that an LCS MCM mission package (and the associated qualifications of the embarked detachment) is not a one-for-one swap for legacy MCM systems or the LCS surface warfare mission package. Arming LCS with the Naval Strike Missile and the associated mission creep to surface warfare tasking will threaten the proficiency of MCM forces. The AvDet will deploy without the armament for surface warfare, qualifications, readiness requirements, and noncombat expenditure allowance. This demands prioritization by operational commanders for MCM training and readiness throughout the Optimized Fleet Response Plan and during deployment.

Make MCM war-gaming results and analyses easily accessible by personnel at the Naval Surface Mine and Warfare Development Center and Naval Aviation Warfighting Development Center to facilitate development of TTPs and inform training and readiness requirements. Operational plans should reflect limitations of the LCS MCM mission package without legacy MCM systems online. This requires input from HSC, LCS, and expeditionary MCM representatives as war-gaming agencies tabletop these concepts of operation.

Fund MCM exercises to provide opportunities for LCS MCM mission packages to hone TTPs and evaluate current systems. DoD Inspector General Report 2018-140, “Acquisition of the Navy’s Mine Countermeasures Mission Package,” noted that the MH-60S airborne MCM systems received IOC in part because “officials stated that the MCM training squadrons currently working with ALMDS and Archerfish systems have not reported any problems.”25 Exercises designed to mirror the operational tempos of a realistic MCM campaign can provide the systems and manning feedback necessary to drive the technological and organizational modifications required to reduce the burden on minimally manned LCS AvDets. Some of the technological upgrades (such as the compatibility and installation of aircraft survivability equipment and the multispectral targeting system) demand immediate attention for nonpermissive operations.

Post-mission Analysis

New technology and innovative force structuring for MCM provide an opportunity for efficient and tailored mission packages designed for specific theater needs. As Department of the Navy operations turn attention back to sea control in the oceans and littorals, leaders must prevent constrained budgets and supply-based readiness from disabling new MCM forces in their operational infancy. A system of systems provides flexibility and adaptability to combat the full range of adversary mine warfare. The LCS MCM mission package and the supporting units, however, require funding for system upgrades, operational testing, and strategic war gaming to determine if the projected model mitigates the current threat. The enemy recognizes our vulnerability. It is time to close the gap.

1. ADM Richardson, A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority Version 2.0 (December 2018).

2. Greg Mapson, “Sea Mines and the Chinese Threat: An Australian Perspective. Second Line of Defense,” SLCinfo.com, 1 May 2020.

3, CAPT Gregory Cornish, USN, U.S. Naval Mine Warfare Strategy: Analysis of the Way Ahead (Carlisle Barracks, PA: U.S. Army War College, July 2003).

4. Cornish, U.S. Naval Mine Warfare Strategy, 14.

5. Mapson, “Sea Mines and the Chinese Threat.”

6. Mapson.

7. Andrew Erickson, Lyle Goldstein, and William Murray, Chinese Mine Warfare: a PLA Navy ‘Assassin’s Mace’ Capability (Newport, RI: CMSI Redbooks, 2009).

8. Mapson, “Sea Mines and the Chinese Threat.

9. Mapson.

10. Mapson.

11. Bradley Martin, Michael McMahon, Jessie Riposo, James Kallimani, Angelena Bohman, Alyssa Ramos, and Abby Schendt, A Strategic Assessment of the Future of U.S. Navy Ship Maintenance: Challenges and Opportunities, (Santa Monica, CA: Rand Corporation, 2017).

12. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Report to Congress on the Annual Long-Range Plan for Construction of Naval Vessels for Fiscal Year 2020 (9 December 2020), 7.

13. Office of the Chief of Naval Operations, Report to Congress.

14. LT Joshua Price, interviewed with LT Rob Swain, 7 August 2020.

15. Megan Eckstein, “Expeditionary Minehunting Units Growing in Size, Capabilities,” USNI News, 4 March 2019.

16. Eckstein, “Expeditionary Minehunting Units Growing in Size, Capabilities.”

17. LT Riley Mcguire, USNR, interviewed with LT Rob Swain, 4 August 2020.

18. Department of the Defense Office of Inspector General, DODIG-2018-140: Acquisition of the Navy’s Mine Countermeasures Mission Package (25 July 2018), 3-4.

19. LCDR Gatlin Hardin, USN, interviewed with LT Rob Swain, 14 August 2020.

20. Department of the Defense Office of Inspector General, Acquisition of the Navy’s Mine Countermeasures Mission Package, 3-4. In 2018, a DoD Inspector General report investigated whether the Navy is effectively managing the development of a mine countermeasures mission package that will allow the LCS to detect and neutralize or avoid mines in support of fleet operations. The IG found that the Navy declared IOC for the three MCM mission package systems reviewed (AMNS, ALMDS, COBRA) prior to demonstrating that the systems were effective and suitable for their intended operational uses and delivered units that have known performance problems to the fleet for use on board the LCS.

21. LCDR David Burkett, USN, interviewed with LT Rob Swain, 11 August 2020.

22. AWS1 Alec Jones, USN, interviewed with LT Rob Swain, 5 August 2020.

23. MNCM Gregory Hartman, interviewed with LCDR Ryan Easton, 11 OCT 2020.

24. Cornish, U.S. Naval Mine Warfare Strategy, 19.

25. Department of the Defense Office of Inspector General, Acquisition of the Navy’s Mine Countermeasures Mission Package.