Conversations about race are unnatural to many in special operations, but the flood of protests following George Floyd’s 25 May death in Minneapolis has sparked an uncomfortable discourse for many in our nation. Racist and sexist comments made in June by a U.S. Naval Academy graduate—a retired Navy captain—exposed how important these conversations are for the Navy. His long-hidden sentiments struck a nerve with me, along with many in our proud Naval Academy alumni community. These views held by a community leader call into question whether there is an undercurrent of sexism—or particularly racism—within the Navy and within the special operations community, of which I am a member.

Uncomfortable Conversations Are Needed

On reflection, my personal experiences suggest that racist sentiments are more prevalent than some would like to admit. As a trainee at Basic Underwater Demolition/SEAL training (BUD/S), a senior SEAL captain observing training called out the only other black SEAL candidate and me. “How are my two little cookies doing?” he asked.

Midway through my career, a senior enlisted leader—a combat mentor and idol to many in my unit—announced, “I am a racist bastard—but I will always support you.” Some would dismiss the first example as a term of endearment by a well-intentioned old sailor. The second example could also be explained away as a flawed man loyally carrying out his military duties, despite his prejudice. Rationalizing either example is wrong. Bigoted insults and overt racism go against our Special Operations Forces (SOF) ethos and the Navy’s core values of honor, courage, and commitment.

Despite these experiences, I have found that most in uniform with whom I have served do not subscribe to or accept these sentiments. A white alumnus from the Academy class of 1958 inspired me to apply to the Naval Academy. He was from a generation in which prejudice was even more prevalent and accepted—a full two generations preceding the disgraced alumni mentioned here. Yet, this honorable officer emerged as a youth mentor and remains one of my strongest advocates. It was a white female Naval Academy classmate who helped teach me to swim and provided a foundation to succeed at BUD/S.

It clearly is possible to succeed in our Navy regardless of race. I was the first black officer to command a SEAL team and helped shape the community in which I serve. If an undercurrent of racism exists, then I must have been affected. Perhaps I did not see the signs and even unknowingly contributed to the problem.

Discussing race does not come easily to special operators, and certainly not to me. In Naval Special Warfare, we are forged and find unity through shared pain at BUD/S. Our rigorous selection process and call to serve the nation is what binds us. For me, there are only two colors in the military: camouflage dark green and light green. My approach to service has been to always keep this principle in mind, but it may have served as a barrier to an enriched understanding and productive conversations on race.

Diversity Uproots Racism

Diversity is a strategic imperative for the special operations community. Over the past couple of months, a groundswell of both minority and nonminority advocates, including those previously reluctant to enter the discussion, have joined the effort to address bias and bigotry. These include influential midcareer professionals spanning academia, the private sector, and the uniformed services. All are eager to share their experiences and offer solutions to improve diversity.

A diverse team—consisting of members from vastly different ethnic and educational backgrounds, life experiences, and geographical locations—has a better chance of finding creative and unorthodox solutions to the complex problems that we must address to win. Diversity is the fuel that helps root out racism; it creates a virtuous cycle that both increases our lethality and brings us closer to fully realizing our SOF ethos and Navy core values.

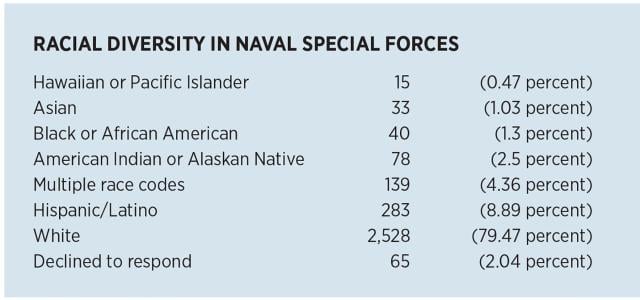

Naval Special Warfare diversity, in particular, remains low. The demography of active-duty SEALs (at left, data from February 2019) illustrates the need for improvement.

A Case for Optimism

There is a growing force of cultural change agents emerging within the military. More young groundbreakers such as Lieutenant (junior grade) Madeline Swegle, the Navy’s first black female tactical jet aviator, are setting new standards. Future leaders, such as the first woman to complete the Army’s Special Forces Qualification Course (Green Beret) in July 2020 are paving the way. These pioneers will need leadership—particularly from the senior mentors now coming forward—to capitalize on this unprecedented opportunity to eliminate racial and gender-based obstacles. We must encourage and support their ability to speak out now against racism and sexism—long before their middle or senior career points.

There have been five months of unrest following George Floyd’s death, and now it is time for emotional sobriety. We must continue to reflect seriously and to look ahead. Less than a week after reporting to the U.S. Special Operations Command headquarters, for the first time in 21 years of service, I was asked to help strategize methods to broaden opportunities and improve diversity within special operations. The commanding general has established a Diversity and Inclusion Board, focused on developing a strategic plan to enhance organizational culture and climate, recruitment, education, and Special Operations Forces diversity. The right people are listening and taking action.

While I was in command, I saw first hand why traditionally the military has set the pace for racial progress in the United States. Our Special Operations Task Force mentored several East African partners in a combined effort to counter violent extremists. On a daily basis our task force—which predominantly lacked diversity—risked life and limb for people of color in a contested volatile environment. It was their enculturated inclination to assume additional, elevated personal risk to protect our partners. We maintained a rigorous mission approval process to address this fundamental drive to protect our partners, safeguard civilian lives, and foster a better quality of life in emerging nations. These patriotic Americans, many heroes, are worthy examples to the most frustrated and underprivileged in our society.

Most U.S. service members continue to display the compassion and decency expected of leaders in uniform, and the bravery to confront racism and sexism both within and outside the military. The selfless example set by these men and women are the reason I continue to serve and recommend a career in special operations to people of all backgrounds. We should all remain optimistic that, as these men and women impact others—in and out of uniform—they will serve as an important catalyst for continued progress in America.