Naval warfare has changed the course of history and decided the fate of nations. On occasion, one side has had an overwhelming preponderance of men and materiel and dominated the adversary through sheer force of numbers. In most cases, however, the actions of the naval commanders are what turned the tide of battle. From Salamis to Trafalgar, Jutland, Midway, and many more naval battles, the commander leading the victorious force made decisions that were better, faster, and more precise than those of the enemy.

Today’s naval commanders must make the same kind of important decisions their forbears made, but with a distinct difference. While Nelson at Trafalgar had hours to make the choice to sail his outnumbered ships perpendicular to the French and Spanish fleet, today’s strike group commanders have only minutes or even seconds to make equally significant judgments.

To help its war-fighters make more effective decisions, the Navy is seeking to harness big data, artificial intelligence (AI), and machine learning (ML) to give its commanders the edge in combat—and to embed these technologies in its platforms, systems, sensors, and weapons. To do so, it depends on technology companies developing cutting-edge commercial products to produce algorithms for military use. But as these businesses continue to develop commercial technologies to take the human out of the loop, is the Navy in danger of taking its warfighters out of the loop as well? Is it prepared for the kind of warfare that would engender?

Drowning in a Sea of Data

For centuries, commanders have struggled to collect enough information to give them the edge in combat. As the Duke of Wellington said, “All the business of war is to endeavour to find out what you don’t know by what you do; that’s what I call guessing what’s on the other side of the hill.”1

The Battle of Midway turned on one commander having more of the right information than the enemy: U.S. Navy PBY scout planes located the Japanese carriers first, while the Japanese Imperial Navy found the U.S. Navy carriers too late to launch an effective attack. Had Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto learned the location of his adversary’s carriers just a bit sooner, he might well have been victorious.2

Those World War II commanders likely would be envious of the amount of information today’s naval warfighters have at their disposal, but they should not be. In the past several decades, the quantity of information available to those in the midst of battle has increased dramatically, but it has not, as promised, lifted the “fog of war.” The U.S. military has demonstrated an excellent ability to collect data, but this deluge of digits has not enhanced warfighting effectiveness.3

A former Vice Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff complained that a single Air Force Predator can collect enough video in one day to occupy 19 analysts. He noted, “Today an analyst sits there and stares at Death TV for hours on end, trying to find the single target or see something move. It’s just a waste of manpower.”4 The data overload challenge is so serious that it is widely estimated that the Navy soon will face a “tipping point,” after which it no longer will be able to process all the data it is compiling.5

The Department of Defense (DoD) has recognized that war-fighters drowning in data cannot make effective decisions and has sought to harness technologies such as big data, AI, and machine learning to help curate the data and present only information that is useful in the heat of battle. However, the devil is in the details.

What’s Old Is New

A taxonomy for making better decisions has been ingrained in the military’s DNA for well more than a half-century. At the height of the Korean War, Air Force Colonel John Boyd created the OODA loop—observe, orient, decide, and act—as a theory for achieving success in air-to-air combat. His idea is that the decision cycle, or OODA loop, is the process by which an individual reacts to an event, and the key to victory is to create situations where one can make appropriate decisions more quickly than one’s opponent.Harry Hillaker—chief designer of the F-16—explained, “The pilot who goes through the OODA cycle in the shortest time prevails because his opponent is caught responding to situations that have already changed.”6

For decades, the U.S. military has sought to achieve superiority on the battlefield by developing technologies to address all four aspects of the OODA loop, and it has been successful—to a point. In a June 2017 address at the Naval War College Current Strategy Forum, then–Chief of Naval Operations Admiral John Richardson used the OODA loop to discuss the kinds of new technologies the Navy is fielding. He noted that the Navy has invested heavily in the observe and act parts of Boyd’s taxonomy, but it could not do much about the orient and decide aspects until the advent of emerging technologies such as big data, machine learning, and artificial intelligence.7

Admiral Richardson noted that today’s naval warfighters have an enormous—even overwhelming—amount of data to deal with. They need artificial intelligence and machine learning to curate this data to present only that information that helps decision makers and those pulling the trigger make better decisions faster.

The problem is that the Navy does not have an enviable record of adapting new technologies to enable officers and sailors to make better decisions. Earlier this century, the Navy laboratory community developed a number of cutting-edge technologies, such as the Multi-Modal Watch Station, Composable FORCEnet, and Knowledge Wall, focused on helping decision makers make decisions faster with fewer people and fewer mistakes. None of these technologies made it into Navy systems.

While the reasons for this failure are complex, what is beyond argument is that the challenge of harnessing AI technologies is even greater. AI cannot be “binned” into any of the Navy’s traditional acquisition stovepipes. In a recent address at the Naval War College, Joint Artificial Intelligence Center director Lieutenant General Jack Shanahan explained:

AI is like electricity or computers. Like electricity, AI is a transformative, general-purpose enabling technology capable of being used for good or for evil—but not a thing unto itself. It is not a weapons system, a gadget or a widget.8

The general’s remarks highlight the difficulty of developing advocacy for big data, artificial intelligence, and machine learning in the military and in the industries that traditionally have provided the military with platforms, systems, sensors, and weapons. But there is another factor that may well influence the ability—and willingness—of the U.S. military to harness the AI technologies developed by the five big tech companies and those like them.9

Have Humans Been ‘Dumbed Down’?

The technology companies the military wishes to engage to provide AI have worked assiduously to have their technologies not just assist human operators, but dominate and even control them. A few examples illustrate how widespread the practice of taking the human out of the loop has become:

- In Amazon fulfillment centers, if a worker who stows items attempts to place an item in the wrong bin, the bin will light up to signal this is not allowed. In addition, Amazon is now beta testing a system where the bin holding the needed screwdriver or watch or toy simply lights up, turning the exercise into a gentle game of Whack-A-Mole.

- At insurance giant MetLife’s call centers, customer service representatives are not monitored by human supervisors, but by AI. When an agent is speaking with a customer, he keeps one eye on the bottom-right corner of his screen. There, in a small box, AI tells him how he is doing. Talking too fast? The program flashes an icon of a speedometer, indicating he should slow down. Sound sleepy? The software displays an “energy cue,” with a picture of a coffee cup. Not empathetic enough? A heart icon pops up.

- At Uber and other ride-hailing apps, the algorithmic manager watches everything the driver does. The “boss” displays selected statistics to individual drivers as motivating tools, such as “You’re in the top 10 percent of partners!” Uber uses the accelerometer in drivers’ phones along with GPS to track their performance in granular detail. One driver posted to a forum that a grade of 210 out of 247 “smooth accelerations” earned a “Great work!” from the boss, an algorithm.

- Fast-food giant McDonald’s is rolling out a system at its drive-throughs that merges an image of the vehicle’s license plate with what the occupants ordered. The next time that vehicle enters the drive-through queue, the board displaying what food is available places the item that was ordered last time in a prominent place. This achieves two goals: It allows McDonald’s to upsell the customer (displaying the “meal deal,” not just the burger) and also keeps the queue moving.

- Drivers of the hybrid gas-electric Ford Fusion need to do little thinking to optimize the vehicle’s energy savings. If they are using gas when they could be functioning in the electric mode, the car’s “intelligent assistant” displays a sea of green leaves to show the driver he or she is not being sufficiently “green.”

These are just a few of the growing number of examples where humans not only are being taken out of the loop, but are yielding control to their algorithmic masters. Concerns about this human-machine imbalance are appearing in the informed literature. For example, two psychologists addressed the pernicious way in which people allow technology to be too dominant:

To navigate by GPS is to ensure a series of meaningless pauses at the end of which you do precisely what you are told. There is something deeply dehumanizing about this. Indeed, in an important sense, this experience turns you into an automated device GPS can use to arrive at its destination.10

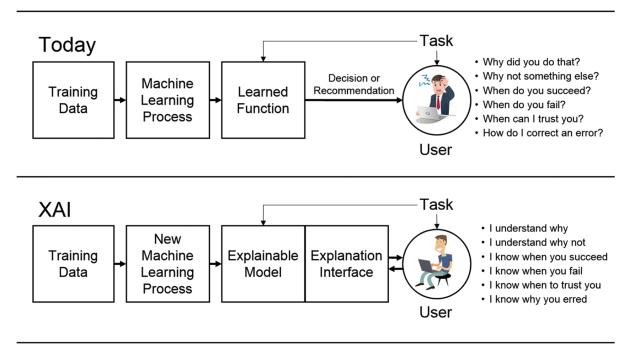

With such powerful forces acting on humans who operate AI-enabled military weapons, it is imperative that those acquiring these systems ensure that the human remains the master of the machine and that what the black box is doing is completely transparent to the operator. Said another way, these systems must have explainability as a first-order criterion. DARPA’s Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) program is a step—but only one step—in this direction.11

Accelerating Adoption—But Carefully

U.S. peer adversaries understand the critical importance of harnessing AI in their military systems. Leaders at the highest levels of the U.S. military understand this importance as well and are keen to keep one step ahead of those who challenge our national security.12 As the National Defense Strategy notes, “America’s military has no preordained right to victory on the battlefield.”

There are two ways for the United States to lose today’s AI arms race. The first is to fail to embrace AI as a technology that can give warfighters a decisive edge in combat, especially in the area of decision-making. But the other way is to not procure AI-enabled military systems that not only keep the human in the loop, but also ensure that the U.S. warfighter is the dominant partner in the human-machine team.

1. Duke of Wellington, cited in Louis Jennings, ed., The Correspondence and Diaries of the Late Right Honourable John Wilson Croker, Secretary to the Admiralty from 1809 to 1830 (Albemarle Street, London: John Murray, 1885).

2. Craig Symonds, The Battle of Midway (Oxford, U.K.: Oxford University Press, 2011).

3. JASON Report, Perspectives on Research in Artificial Intelligence and Artificial General Intelligence Relevant to DoD (McLean, VA: The MITRE Corporation, January 2017), https://fas.org/irp/agency/dod/jason/ai-dod.pdf.

4. Ellen Nakashima and Craig Whitlock, “Air Force’s New Tool: ‘We Can See Everything,’” The Washington Post, 2 January 2011.

5. See a TCPED study by the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations and PMW 120 (Battlespace Awareness and Information Operations), an independent Navy Cyber Forces study, and the 2010 NRAC Summer Study.

6. Harry Hillaker, “John Boyd, Father of the F-16,” Code One, July 1997.

7. A video of the CNO’s remarks can be found at www.youtube.com/playlist?list=PLam-yp5uUR1ZUIyggfS_xqbQ0wAUrGoSo.

8. LGEN Jack Shanahan, USAF, U.S. Naval War College Address, “The Challenges and Opportunities of Fielding Artificial Intelligence Technology in the U.S. Military,” 12 December 2019.

9. Most prominently, the so-called FAANG Five (Facebook, Apple, Amazon, Netflix and Alphabet’s Google).

10. Hubert Dryfus and Sean Dorrance Kelly, All Things Shining: Reading the Western Classics to Find Meaning in a Secular Age (Tampa, FL: Free Press, 2011).

11. See DARPA’s Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) website for more information: www.darpa.mil/program/explainable-artificial-intelligence.

12. See, for example, Ben Werner, “Pentagon Falling Behind in Using Artificial Intelligence on the Battlefield,” USNI News, 22 October 2019, and Ben Werner, “Panel: U.S. Military Artificial Intelligence Effort Underfunded, Understaffed,” USNI News, 23 October 2019.