Decentralized command is a hallmark of the Navy and Marine Corps team. Its tenets go hand in hand with maneuver warfare, and empowering subordinates to act on commander’s intent is the most effective way to weaponize tempo at both the operational and tactical levels. Through numerous conflicts, the sea services have evolved to appreciate the necessity for mission orders and decentralized command.

With advances in technology, however, national command authorities now can have an active say in military operations down to the tactical level. There clearly is value in instantaneous communications, but the potential downside is alarming. If a senior civilian or military leader were to lose confidence in a particular plan, operation, or commander, he or she no longer would have to use the chain of command but could reach down directly into the fight in real time and direct forces. This would negate almost 250 years of command evolution.

Evolution of Command at Sea

In the early days of the Navy, decentralized command was a requirement for operations. When the only long-range communications available were letters traveling by sail, a naval vessel’s orders had to be general enough to ensure they would be enduring yet leave no doubt as to the commander’s intent.

During the War for Independence, the Continental Navy had broad orders to protect American shipping and disrupt British commerce. There is little doubt that Captain Lambert Wickes commanding the frigate Reprisal understood the commander’s intent. After depositing Benjamin Franklin in France, his orders were to “proceed directly on the coast of England.”1 Operating from French ports and with no lines of communication with Continental leaders, early American sea captains such as John Paul Jones engaged, raided, and took prisoners up and down the British coast.

Sailing from Hampton Roads on board the USS Constellation in 1799 during the Quasi-War with France, Captain Thomas Truxtun’s only orders were to keep his squadron “constantly cruising. You cannot be too adventurous. We have nothing to fear but from want of enterprise.”2 Which sea lanes he would patrol, how to split his forces, and even when to return home were up to Truxtun.

By the War of 1812, decentralized command was well established among America’s sea captains. They had a liberal understanding of the limits of their orders and discretion for the best way to carry them out.

During World War II’s Pacific campaign, approaching the Battle of Midway, Admiral Chester Nimitz had a clear battle concept, which he communicated to Admirals Raymond Spruance and Frank Fletcher, as well as to “all who needed it so that they could turn it into a reality.”3 He left much discretion to subordinates. Aircraft carrier captains were ordered to “protect Midway by finding and attacking Japanese carriers . . . governed by the principle of calculated risk.”4 Nimitz was providing opportunity for unit commanders to update the plan if unforeseen opportunities for great rewards appeared.

Speed of action, empowering subordinates, and clear commander’s intent would continue to play a role in later military successes, such as the Inchon landing in Korea, the invasion of Grenada, and the invasion of Panama. These concepts would be codified as maneuver warfare in the 1980s and showcased again in the first Gulf War.

Barriers to Decentralized Command and Mission Orders

Commander’s intent, mission orders, and empowering subordinates are not naturally occurring. Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority Version 2.0 states “the current security environment demands that the Navy be prepared at all levels for decentralized operations, guided by commander’s intent.” Today, three major barriers to decentralized command are prevalent.

• Unwillingness to accept the risk of subordinates’ potential failure. Commanders can always delegate authority, but they can never delegate accountability. Using commander’s intent and empowering subordinates incurs risk. In the event of a failure, the commanding officer will bear accountability.

In General George Marshall’s Army in World War II, acceptance of risk was forced on commanders. Failure to achieve a record of success resulted in removal from command. Today, Navy commanders more often are relieved for sexual or fiscal indiscretions than for failures in performance, and given that the nation is not currently involved in a high-intensity conflict, that should not be a surprise. Nevertheless, as British Army Major Jim Storr notes, if something goes wrong, someone will be blamed. “There is a ‘fall guy,’” he writes, “not least because the media, with their need for immediate but often simplistic messages, want someone to be seen to be blamed.”5 An important element in implementing decentralized command and the use of commander’s intent, he argues, is mutual trust and acceptance by a superior of a well-intentioned mistake.

• A desire at the highest levels of command and government for in-depth unit-level information and reporting. To satisfy this desire, some senior commanders attempt to control decision-making at the lowest levels of command. Enjoying military superiority over the past 25 years has allowed the United States to become very efficient in manning, training, and equipping its military, but with no real ability to absorb large-scale turbulence in any particular domain.

The Navy strike-fighter community experienced this recently. From low year-group accessions and poor retention to the T-45 grounding and F/A-18 maintenance backlog, the result was a force stretched thin and a failure to meet readiness goals. In this situation, the most senior leaders must meticulously manage manning, training, and equipping for all units. There is no room for error, or even commander’s discretion, when a decision by one unit commander can have an impact on the entire community. The only way to muddle through such turbulent times is a community-wide game plan.

• An operating environment where decisions by junior personnel can have far-reaching strategic effects. The Navy and Marine Corps are high reliability organizations, where a mistake at the lowest level can have a disproportionately large effect on the organization as a whole. If a young sailor fails to properly inspect a maintenance action on an aircraft, for example, there is the possibility of catastrophe and loss of life.

In World War II, the forces under General Omar Bradley scored many successes, but they also recorded a disturbing number of botched battles and missed chances.6 Some of these failures probably resulted from tactical mistakes, but it is unlikely any one tactical error changed the strategic landscape in 1944. However, today the mistakes, inaction, or improper actions of junior operators could have dire strategic and national policy implications. The accidental strikes on fuel trucks that killed a number of Afghan women and children, on a Doctors without Borders hospital that killed 22 people, and the killing of 24 Iraqi civilians in Haditha are just a few examples of operators affecting the entire strategic landscape.7

In a high reliability strategic landscape, reach down by high-level leaders into daily operations at the unit level should not be surprising. The management and execution of national strategy no longer stops at the implementation of diplomatic, information, military, and economic decisions.

The Communications Conundrum

We are in the midst of another technological revolution; one that offers many possibilities for command and control and—as with most “game changers”—many conundrums as well.

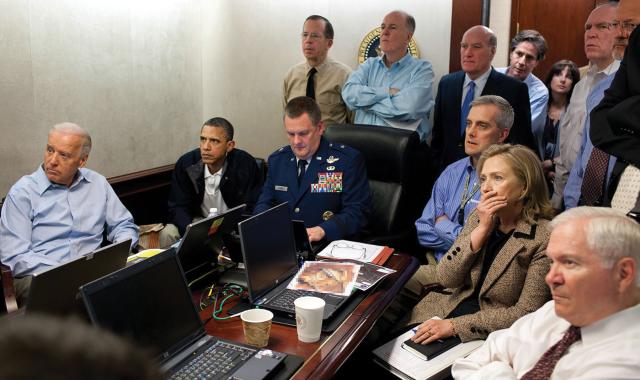

On 1 May 2011, the White House photographer took what would become an iconic photograph of the Obama presidency: national leaders watching the raid on the bin Laden compound in real time. The video feed was being relayed from a drone overhead. The alarming possibilities of such a capability were summed up by then-Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff Admiral Mike Mullen. After one of the two helicopters crashed, his biggest concern “was that someone at the White House would reach in and start micromanaging the mission. It is potentially the great disadvantage about technology that we have these days. And I was going to put my body in the way of trying to stop that. Obviously, there was one person I couldn’t stop doing that, and that was the president.”8

But what if the President had wanted to step in? What if a less trusting leader had decided to take over operational command of the raid?

It is not unimaginable that in a few years it will be possible to put the President of the United States in voice communication with a pilot in the cockpit of a fighter jet or the leader of a SEAL team. This should give pause to any senior leader who believes in decentralized command. If the Navy and Marine Corps are to continue to adhere to the concepts of mission orders and maneuver warfare, they must value individual initiative and responsibility. This will require senior leaders to refrain from doing some things that are technologically possible.

Senior leaders must inoculate themselves now against the oversupervision of subordinates. The commencement of high-intensity conflict is not the time to have to resurrect decentralized command. We must practice and strengthen implicit communication, commander’s intent, and time-competitive decision-making. We must learn to thrive in “an environment of chaos, uncertainty, constant change, and friction.”9 Navy and Marine Corps leaders must not allow technology to lead them toward a centralized command mind-set, as it will certainly result in slow decision-making, delay of action, missed opportunities, and likely mission failure. By making the decision now, in relative peace, to implement and maintain decentralized command, we can outpace our adversaries and be decisive in combat.

How different 2 May 2011 would have been if after the helicopter crashed into the bin Laden compound all radios had echoed with “POTUS Directs Mission Abort!”

1. Stephen Howarth, To Shining Sea: A History of the United States Navy, 1775–1998 (Norman, OK: University of Oklahoma Press, 1999), 13–16, 30.

2. Ian W. Toll, Six Frigates: The Epic History of the Founding of the U.S. Navy (New York: W. W. Norton & Company, 2006), 131.

3. Carl H. Builder, Steven C. Bankes, and Richard Nordin, Command Concepts: A Theory Derived from the Practice of Command and Control (Santa Monica, CA: RAND, 1999), 42.

4. Builder, et al., Command Concepts, 32.

5. Jim Storr, “A Command Philosophy for the Information Age: The Continuing Relevance of Mission Command,” Defence Studies (Autumn 2003): 119–29.

6. Thomas E. Ricks, The Generals: American Military Command from World War II to Today (New York: The Penguin Press, 2012), 117.

7. “NATO Airstrike on Afghanistan Fuel Truck Kills 40,” The Telegraph, 4 September 2009; Eric Schmitt and Matthew Rosenberg, “General Is Said to Think Afghan Hospital Airstrike Broke U.S. Rules,” The New York Times, 6 October 2015; and James Joyner, “Why We Should Be Glad the Haditha Massacre Marine Got No Jail Time,” The Atlantic, 25 January 2012.

8. Jamie Crawford, “The bin Laden Situation Room Revisited—One Year Later,” CNN, 1 May 2012.

9. U.S. Marine Corps, Warfighting (San Bernardino, CA: Renaissance Classics, 2012), 23, 52.