Concentration of force is a fundamental principle of war, expressed in joint doctrine as mass: “The purpose of mass is to concentrate the effects of combat power at the most advantageous place and time to produce decisive results.”1 From the late 1940s through the end of the Cold War, the Navy’s force structure was adequate to achieve strategic concentration when and where necessary: The service could keep forces constantly on station at three key areas on the Eurasian periphery while also maintaining the capability to surge additional forces if trouble erupted. After 1992, force drawdowns gradually constricted the Navy’s ability not only to keep station but also to achieve strategic concentration through surge. In a stable world in which the key threat has been terrorism, this has not had discernible strategic consequences, but with China building a powerful navy that threatens not only Far East friends and allies, but also the whole regime of freedom of the seas, the situation is becoming increasingly dire.

The Navy has adopted a two-pronged strategy to deal with the force deficiency it now faces. The first is a strategic deployment scheme it calls “dynamic force employment,” in which carrier strike groups and amphibious ready groups deploy in a manner unpredictable to potential enemies. This is a logical fallback strategy when force levels are insufficient to populate stations continuously, but it does not solve the problem of insufficient forces to achieve strategic concentration.

The second prong is the effort to increase overall fleet size. As Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Michael Gilday’s fragmentary order on Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority Version 2.0 states, numbers matter.2 The admiral calls for reexamining the 30-year shipbuilding plan and developing both manned and unmanned platforms to provide fleet commanders overwhelming fires. This is desirable, but current budgetary and industrial capacity conditions could undercut building plans, and geopolitical events likely will outpace the Navy’s acquisition process.

There is yet another facet of strategic concentration the Navy is struggling with: fleet experimentation and training. At-sea experimentation and training are a necessary foundation for creating combat power using the types of forces currently composing the fleet: aircraft carriers, cruisers, destroyers, etc.3 To that end, Admiral Gilday suggests the Navy in 2020 will learn from fleet battle problems and the Large Scale Exercise (LSE), then “restore annual LSEs as the means by which we operate, train, and experiment with large force elements.” However, it is not clear at this time how forces will be made available for such exercises.

The fleet battle experiments of the late 1990s/early 2000s were mostly smaller scale affairs within individual battle groups and primarily involved network technology. They also suffered from the attempt to superimpose them on normal work-up training.4 Focus is an aspect of concentration, and thus fleet experimentation, to be successful, should be the sole focus of force groupings that are brought together for that purpose.

There are two other potential ways out of the strategic concentration dilemma the Navy faces, assuming it cannot build its way out and is unable to divest itself of its global presence commitments. The first lies in the joint arena.

A few years back, the Navy and Air Force attempted to develop a cooperative concept called “AirSea Battle,” but it was bedeviled by a number of interservice political factors, including the Army and Marine Corps wanting a piece of the action. Eventually it morphed into a broader joint concept called Joint Access Maneuvering in the Global Commons. The new concept “lays out an approach for operations in contested environments that does not rely on overcoming a potential adversary’s A2/AD military capabilities.”5 Nonetheless, it still would seem necessary to effect some kind of strategic concentration to achieve military objectives in the East Asian littoral.

Meanwhile, the Air Force has added an antiship capability to its B-52s and B-1s, and the Marine Corps and Army are developing a coastal-defense antiship missile capability.6 The combined, coordinated effects of joint missile salvos might make distributed operations more effective, but the other services still depend on the Navy to get their forces in place, so it is not clear that any military conflict more than a brief skirmish would be supportable without strategic naval concentration.

Another potential solution surfaced in a Proceedings article entitled “Converting Merchant Ships to Missile Ships for the Win.”7 The authors propose that the Navy purchase existing merchant hulls and mount various types of missiles in them, turning them into commissioned warships. Missiles tend to be platform agnostic, so the issue becomes number of missiles rather than strictly the number and type of ships, which was the determinant of naval power in previous eras.

Converted merchants, being outside the Navy’s normal fleet architecture, could be used strictly for strategic concentration purposes. Moreover, if, as the article suggests, they were manned by reserve or even hybrid crews, they could be forward positioned with only caretaker personnel until circumstances called for their use, much like current Marine Corps and Army prepositioning ships. There would be less need for them to participate in fleet battle experiments, as their missiles would be controlled remotely and training could be accomplished via simulation.

Merchant ship conversion could address another element of strategic concentration: supporting a campaign of indefinite duration. Since the dawn of the nuclear era it has been common wisdom that wars will be fought with the forces in existence at their start, the presumption being that either a quick decision or apocalyptic destruction would moot the idea of an industrial production–based war. There seem to be any number of incentives for current great powers to avoid a drawn-out conflict, but war has a way of imposing its own logic, so the possibility of a long war cannot be disregarded. The notion of “feeding the fight” applies at all three levels of war, and at the strategic level it involves production, including the replacement of losses. In naval terms, this includes ships.

While construction of warships can be accelerated under emergency conditions, the conversion of existing merchant hulls would be the most expeditious way to generate new and replacement forces. As such, the inventory of available merchant hulls would constitute a kind of reserve force. Developing the experience and skills now in the conversion process would greatly facilitate the country’s ability to do so under emergency conditions.

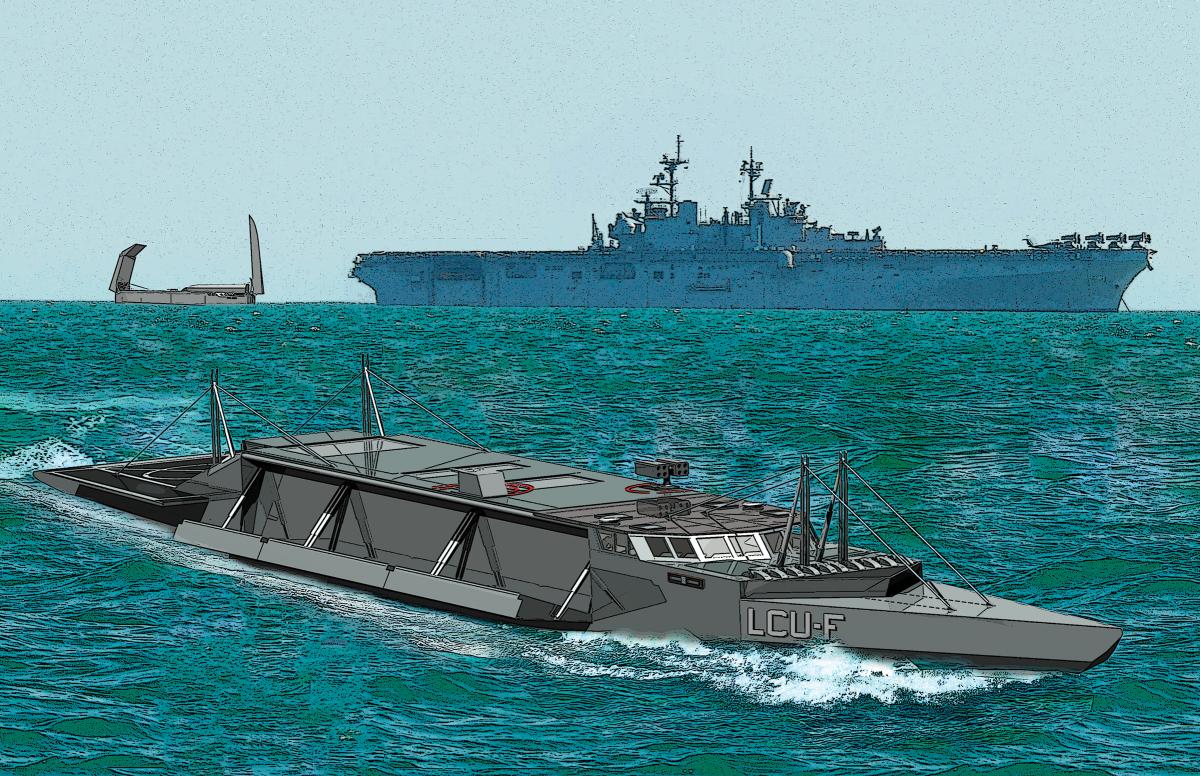

A first cousin to the merchant conversion idea is to retain the soon-to-be retired LSD-41 class as mother ships for an antiship flotilla. The basis for this concept is a new type of folding landing craft, utility (LCU[F]), that has the range, speed, and capacity to function as an antiship missile craft when loaded with one of the mobile launchers the Army and Marine Corps are procuring.8 The LSD-41 could carry six of these craft. It could lurk in archipelagic waters, sending its LCU(F)s out to launch missiles and then run back to the safety of the narrow channels. Since the LCU(F)s also would be capable ship-to-shore connectors, the combination could easily support Army and Marine Corps antiship-missile shore detachments.

These two solutions would offer the additional strategic concentration advantage of being timely, both in when they could be brought online and in their ability to react quickly to emergent operational need. Building more warships is certainly a national need—especially if the United States intends to maintain its support of the current international order and retain or expand its circle of allies and partners—but the necessarily slow and uncertain tempo of shipbuilding and the ponderousness of strategic concentration, moving naval forces thousands of miles, suggests that in the missile age, a different approach is needed. U.S. grand strategy demands strategic dispersal of naval forces. The rising threat from China demands strategic concentration. Missile-centric distributed maritime operations, if supported by joint forces and solutions such as converted merchants, offer the chance for the Navy to achieve both within the likely parameters of future budgets and industrial capacity.

1. Joint Publication 3.0, Joint Operations, 17 January 2017, incorporating Change 1, 22 October 2018, A-2.

2. ADM Michael Gilday, USN, “FRAGO 01/2019: A Design for Maintaining Maritime Superiority,”

3. ADM Scott Swift, USN, “Fleet Problems Offer Opportunities,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 144, no. 3 (March 2018).

4. See Shelly Gallup, Gordon Schacter, and Jack Jensen, Fleet Battle Experiment Juliet Final Reconstruction and Analysis Report (Monterey, CA: Naval Postgraduate School, April 2003), 61–67.

5. Michael Hutchens, et al., “Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons, A New Operational Concept,” Joint Force Quarterly 84, no. 1 (1st Quarter 2017): 134–39.

6. Stephen Carlson, “Lockheed Delivers First LRASM Antiship Missiles for Air Force B-1B Lancer,” United Press International, 18 December 2018; Michael Peck, “Here Is Why the U.S. Marines Want Their Own Anti-Ship Missiles,” The National Interest, 5 November 2017; and Nikki Ficken, “First Land-based Missile Launch Performed at RIMPAC Exercise,” Army.mil, 27 July 2018.

7. CAPT R. Robinson Harris, USN (Ret.); Andrew Kerr; Kenneth Adams; Christopher Abt; Michael Venn; and COL T. X. Hammes, USMC (Ret.), “Converting Merchant Ships to Missile Ships for the Win,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 145, no. 1 (January 2019).

8. Susanne Altenburger, CDR Michael Bosworth, USN (Ret.), and CAPT Michael Junge, USN, “A Landing Craft for the 21st Century,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 139, no. 7 (July 2013).