In January 1999, then-Marine Corps Commandant General Charles C. Krulak envisioned a new kind of small-unit leader, capable of simultaneously handling humanitarian operations, mid-intensity wars, and military operations other than armed conflict. He defined such a leader and environment in his essay “The Strategic Corporal: Leadership in the Three Block War,” in which he introduced “Corporal Hernandez,” a fictional squad leader who finds himself simultaneously preventing opposing factions from coming to blows, managing violent protests, and deciding whether to send out a rescue team after an international aid helicopter is shot down.

Krulak foresaw such a situation as the “likely battlefield of the 21st century” and predicted that the “rapid diffusion of technology, the growth of a multitude of transnational factors, and the consequences of increasing globalization and economic interdependence” would converge “to create national security challenges remarkable for their complexity.” To prepare for this kind of future, Krulak said junior leaders needed strong character, training, and leadership skills.

More than 20 years later, today’s operating environment is even more complicated than Krulak imagined. Great power competition, cyber, space, electronic, and information warfare, artificial intelligence, long-range precision fires, gray-zone strategies, unmanned systems, and much more contribute to an environment that will require Marines at all ranks to be not only strong leaders, but intellectual warfighters as well.

Recognizing this need, the Joint Chiefs of Staff publication, “Developing Today’s Joint Officers for Tomorrow’s Ways of War” includes a vision for overhauling professional military education to create “strategically minded joint warfighters, who think critically and can creatively apply military power to inform national strategy, conduct globally integrated operations, and fight under conditions of disruptive change.”

Most of this focus, however, has been on officer and not enlisted professional military education (PME). While it is important to address officer PME, what is just as important is the education of our most junior members and leaders—the strategic corporals and lance corporals who spearhead the fight.

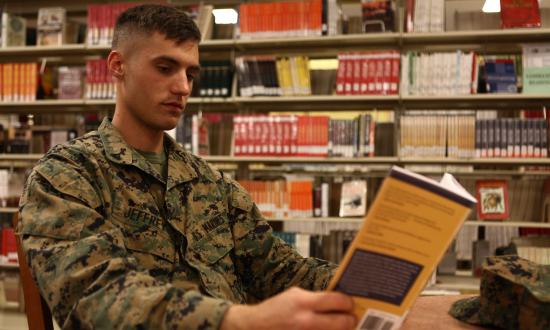

To prepare for the emerging operating environment, PME for junior Marines and leaders must be expanded. If the Marine Corps intends to create warrior-scholars who can effectively operate in complex and contested environments as part of distributed operations, it must implement a continuous education curriculum that instills the intellectual edge Marines will need.

A New Kind of War

The need for more educated junior leaders has been well documented since the publication of Krulak’s “Strategic Corporal” essay. In 2002, then-Chief of the Australian Army Lieutenant General Peter Leahy stated that the time for Krulak’s junior leader concept had arrived.

“The era of the strategic corporal is here,” Leahy said. “The soldier of today must possess professional mastery of warfare, but match this with political and media sensitivity.”

A number of studies supporting or criticizing the concept of the Strategic Corporal followed. In 2006, Major T.M. Scott argued in “Future War Paper: Enhancing the Future Strategic Corporal” that future conflicts would require junior leaders with a minimum of the following skills:

individual initiative, cultural sensitivity, media awareness, mediation skills, linguistic competence, mastery of sophisticated weapons and sensors, and a capacity for small group operations. . . Although a deliberate and focused training regime is necessary to enhance professional mastery, the future Strategic Corporal will require more than just skill and technical proficiency to perform his tasks. To complement training, the junior leader must also have a broader understanding of concepts and processes, and the knowledge and understanding to justify his tactical actions within the overarching operational or campaign goals.

Recognizing the uncertainty inherent in future conflicts, Scott emphasized the importance of education. “Indeed, if training prepares the individual to respond to a predictable situation or circumstance, while education prepares them for unpredictable situations, then the requirement for relevant and effective education becomes critical.”

Scott’s writing was mostly focused on the low-intensity wars unfolding in Iraq and Afghanistan. As the United States transitions from this kind of conflict to great power competition with Russia and China and a future of greater uncertainty, the imperative for educated junior Marines becomes even more crucial.

To get an idea of the complex and contested environments Marines will face, look at Syria. What began as a civil war in 2011 has spiraled into a global quagmire. Within the borders of one country, government and rebel forces have engaged in a civil war with the backing of several outside powers; the United States has led a global coalition against the Islamic State; Turkey has created a buffer zone inside northern Syria that led to clashes with U.S.-partnered Kurdish troops and Russian-backed regime forces; and U.S. and Russian convoys regularly come into provocative contact with one another, with one incident leading to the injury of four American troops. All of this is, admittedly, a gross understatement of the complexity of the situation in Syria, but it provides a snapshot of the future operating environment that Marines will likely find themselves in. That is, politically complex arenas involving multiple actors—including possibly competing great powers—operating in close proximity with varying interests and military capabilities.

Earlier this year, Marine Corps Commandant General David H. Berger noted the proliferation of precision strike weapons and gray-zone strategies in the maritime domain as the primary challenges shaping force modernization and that the Indo-Pacific and China would be the Corps’ primary focus. The New York Times reported in February that Russian and Syrian actions “are devised to present a constant set of challenges, probes and encroachments to slowly create new facts on the ground and make the U.S. military presence there more tenuous.” U.S. forces operating in Syria have had to show considerable restraint, professionalism, bearing, and tact in how they have handled Kurdish-Turkish relations, contact with Syrian forces, and Russian aggression. Marines operating in the Indo-Pacific might find themselves walking similarly delicate lines.

they have in the counterterrorism and counterinsurgency operations of the past 20 years.

A Continuous Education Curriculum for Junior Marines and Leaders

Marine Corps Doctrinal Publication 7 notes that “training prepares Marines to deal with the known factors of war . . . while education prepares Marines to deal with the unknown factors.” Given that the future operating environment promises plenty of unknowns, the Marine Corps must prioritize education to the same degree it does physical fitness and training by regularly setting aside time within training schedules for intellectual development.

A continuous education curriculum that educates Marines on the factors and challenges that are shaping the emerging operating environment would be ideal. To meet the different needs and operational tempos of units, a curriculum could be provided to units by the College of Distance Education and Training via MarineNet. Materials such as case studies, videos, articles, journals, and tactical decision games pertaining to various topics and designed for group discussion and learning would be available in digital libraries. A small number of Marines at the company or platoon level, identified for promising teacher/instructor skills, would then use these materials to conduct regular classes in a manner suited to their company/platoon.

Recognizing that education and training are not distinct but in fact interdependent, consistent education would complement unit training. Classes could be conducted prior to, during, or after training. The curriculum should be both flexible and adaptable while still providing frequent, in-depth education.

Topics included in such a curriculum would be ones already covered in existing PME as well as those studied more exclusively by officers and senior enlisted, such as cultural, political, regional, economic, and linguistic studies; weapons, systems, tactics, strategies, and doctrines; military history, joint concepts, and information, electronic, cyber, space, traditional, and irregular warfare; and interpersonal, intrapersonal, and communication skills. In addition, such education must complement rigorous, realistic training by teaching Marines not just how to act, but how to think. Like officer PME, junior enlisted PME should develop strong critical, analytical, creative thinking and problem-solving skills, intellect, emotional intelligence, and communication skills.

Cultural, linguistic, political, economic, and regional studies cannot solely be part of pre-deployment training; they must be part of continuous education throughout Marines’ careers to better prepare them for regions in which they likely will operate. The Regional, Culture, and Language Familiarization (RCLF) Program already provides a framework, but it is restricted to career Marines. The program, or material akin to it, should be taught to all Marines beginning at the earliest point in their careers.

Vicarious learning—that is, learning from others’ experiences—would also be incorporated. “Vicarious experience is critical because even the most realistic training experiences and military education fall short of the reality of combat,” MCDP 7 states. “Therefore, the more vicarious experience that a Marine obtains, the less likely that a new experience, in combat or otherwise, will be completely unique.” Vicarious learning materials could cover both contemporary and historical experiences pertaining to emerging technologies, weapon systems, and operating environments. For example, Marines could study recent Turkish drone strikes on Syrian government forces to better understand the risks posed to armored vehicles by unmanned aircraft in state-on-state conflict.

Educating Marines on these topics would enable them to better understand their commander’s intent and tactfully provide well-informed opinions and advice to senior leaders, thereby fulfilling another tenet of MCDP 7: “The Marine with authority must make the decisions, but ‘until a commander has reached and stated a decision, subordinates should consider it their duty to provide honest, professional opinions even though these may be in disagreement with the senior’s opinions.’”

One may argue that the current PME curriculum already meets these standards. The reality is that what currently exists for sergeants and below are mostly resident courses Marines attend when they advance to the next grade and check-in-the-box, “click-through” MarineNet classes that fail to provide meaningful education. To develop junior warrior-scholars who can meet new and emerging challenges requires continual, in-depth education that covers the same topics studied by officers and senior enlisted.

Assessing the outcomes of continual education would take some figuring out. One possible method could be an educational version of the Marine Corps Combat Readiness Evaluation System that would assess Marines’ knowledge, thereby ensuring that units emphasize intellectual development to the same degree as training and physical fitness.

Successfully operating in today’s highly contested and complex operating environments—against an array of emerging weapon systems and threats—will require Marines to be warrior-scholars. A continual education curriculum will help create those warrior-scholars—at all ranks—who can operate in such environments. The strategic corporal concept was first imagined in light of an operating environment defined by failing and failed states, mid-intensity wars, and operations other than armed conflict in which the U.S. was the preeminent world power. The return to great power competition will likely see a complicated continuation of the proxy and small wars that have defined the first 20 years of this century and an even greater chance for high-end warfare. Thus, the need for strategic corporals will be ever more paramount. Even in the event of high-intensity, state-on-state conflict, corporals could find themselves in strategic roles during distributed operations with limited communications with higher echelons.

At the end of General Krulak’s 1999 essay, Corporal Hernandez assessed the information at hand and ultimately made “the right decisions” that led to de-escalation of the impending crisis. He did so through a combination of strong character, thorough training, and outstanding leadership. The challenges Hernandez faced were not frivolous, but they were only a fraction of those that Marines in the emerging operating environment will encounter. Preparing junior Marines for these future challenges will require expanding PME into continual, in-depth education that complements rigorous training.

Amidst a drastic modernization effort to improve weapons, doctrine, and systems, we must also devote resources to improving the most important weapon of all—the minds of our Marines. War, after all, is a thinking person’s game, and the success of the United States—and indeed the prosperity of liberal democracy and freedom everywhere—will depend on the decisions and actions of America’s young leaders and warfighters.