The scale and speed of China’s naval construction bear only one conclusion: Beijing is seeking to erode U.S. naval supremacy. This judgment requires no specialized knowledge of China or access to top secret intelligence. One need only look at the platforms the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN) is building and the pace at which it is building them.

But to fully understand the nature of the China maritime challenge, one must dig deeper—into the ideas guiding China’s naval development. This is far more difficult. The Chinese military is extremely cautious about revealing its true intentions. It produces lots of media content, but most of it is fluff. Analysts who spend their days sifting through Chinese sources failed to anticipate Beijing’s decision to build three enormous military facilities in the heart of the South China Sea. One day, China just began dredging sand and coral.

Still, many important things cannot be hidden. The service cannot build and shape a fighting force in secret. Major priorities must be communicated and inculcated. Soldiers, sailors, airmen, and rocketeers need to know what is asked of them and why it matters. By necessity, much of this happens in the open. The PLA can conceal plans to build bases; it cannot obscure broader aspirations.

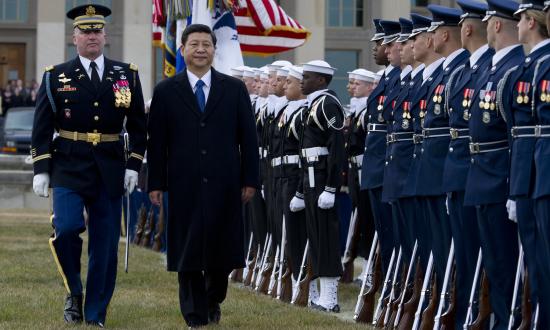

The PLAN’s newest aspiration is to transform itself into a “world-class navy.” The idea of becoming “world class” was not a PLAN invention. Sometime in 2016, China’s head of state Xi Jinping told the PLA to transform itself into a world-class military. This injunction later appeared in Xi’s report at the 19th Party Congress in October 2017, making it the official policy of the Chinese party-state.

The concept means different things for different services. For the PLAN, the clearest articulation appears in a speech delivered by PLAN Commander Vice Admiral Shen Jinlong shortly after the 19th Party Congress.1 The concept has what Admiral Shen calls three “essential features.” Two refer to key attributes of a world-class navy—global reach and command of the sea; the third highlights the process of getting there.

Global Reach

Chinese leaders have carefully avoided discussing the geographic aspirations behind the world-class military concept. In theory, a world-class military does not necessarily imply a global military; it could simply mean a force as capable as the best in the world. For the PLAN, however, leaders have declared an intention to “achieve a metamorphosis from being a regional navy to a world-class navy,” hinting at global aspirations.2 Vice Admiral Shen was even more explicit in his December 2017 speech, stating that the PLAN must “build itself into a navy that possesses extensive influence all around the world.” This, Shen explained, is the first essential feature of a world-class navy.

The global scope of China’s maritime designs should come as no surprise. The PLAN already operates out of area. Every month, its ships transit the Japanese islands, headed for training grounds in the western and central Pacific. Since 2009, Chinese task forces have operated continuously off the Horn of Africa, protecting merchant vessels from Somali pirates. PLAN ships have steamed through the South Atlantic every year since 2014. Meanwhile, the PLAN has telegraphed its intention to defend Chinese interests wherever they extend.3

Chinese “overseas interests” include the security of Chinese people and property, on land and at sea. To date, the PLAN has conducted only two types of operations to protect China’s overseas interests: counterpiracy in the Gulf of Aden and noncombatant evacuation operations (Libya and Yemen). But Chinese leaders clearly intend it to do more. China’s 2015 National Defense White Paper lists “energy and resources” and “institutions” as overseas interests the PLA could be asked to defend.4

Today, the PLAN routinely operates beyond maritime East Asia, but it has largely focused on the Pacific and Indian Oceans. Admiral Shen’s remarks, however, indicate that a robust global presence is only a matter of time. PLAN strategic concepts now openly acknowledge plans for “expansion into the polar regions.”5 Indeed, a prominent Chinese acoustician has suggested that the country’s scientists are actively laying the foundation for future submarine operations in the Arctic Ocean.6

That China intends to build a global navy is awkward for the Chinese to admit, even to themselves. In Chinese textbooks, global navies are the instruments of colonialism and imperialism. Aversion to gunboat diplomacy—a practice used by others to subjugate China during the so-called century of humiliation—is ingrained in the Chinese consciousness. Therefore, Admiral Shen was quick to point out that becoming a global navy did not imply that China would become a “global maritime hegemon.”

Command of the Sea

The second essential feature of world-class navies is that they possess what Admiral Shen calls “world-class command of the sea.” Invented in the West, the term command of the sea is largely outdated in the land of its birth. In China, it retains wide currency. As Chinese strategists see it, navies strive to seize command of the sea from the adversary. Those who prevail can freely use the ocean, while the vanquished can do so only at great risk, if at all.

Command of the sea has been a doctrinal goal since the birth of Chinese naval strategy in the mid-1980s. Under Admiral Liu Huaqing, the PLAN determined it must develop the ability to seize and maintain command of the sea in waters within the first island chain.7 Three decades later, it conceivably has achieved this ability, except in conflicts involving regional states allied with the United States. Chinese strategists believe time is on their side: If current trends continue, it may not be long before the PLAN, working in concert with other services, can operate unmolested in any likely scenario.8

But mastery of the “near seas” has never been the end game for the PLA. The prospect of U.S. military intervention in a regional conflict—made real by the Taiwan Strait crises of 1995–96—forced the Chinese military to expand its horizons. U.S. Navy carrier strike groups could attack Chinese targets from locations well east of the first island chain, in the Philippine Sea. Wars in Iraq and Kosovo demonstrated the awesome power of precision airstrikes and standoff weapons such as Tomahawk cruise missiles.9

For the PLA, these capabilities highlighted the importance of engaging the adversary before his strike aircraft and cruise missiles are in range. This premium on strategic depth drove colossal efforts to build “assassin’s mace” weapons such as antiship ballistic missiles. It also convinced the PLAN of the need to be able to fight beyond the cover of shore-based aircraft and missiles. As early as the 1990s, PLAN strategists argued that the service’s long-term goal should be command of the sea in the northwest Pacific.10

In Admiral Shen’s words, command of the sea is an “eternal topic” within the PLAN. “Those who do not command the sea,” he said, “are commanded by the sea.” He urged his audience to regard it as the “main line of effort” for future development of core military capabilities.

Development Speed

The first two essential features describe goals for PLAN capabilities. For the third, Admiral Shen stressed the process for developing these capabilities. He declared that the PLAN must become a world-class navy as quickly as possible. Speed was paramount.

Here, the PLAN is taking cues from its civilian overlords. In a speech delivered at an April 2018 fleet review, Xi Jinping proclaimed that the “task of building a powerful People’s Navy has never been so urgent as it is today.”11 Earlier in his tenure, Xi offered a “strategic judgment” that has become known as the “three at seas”: The primary threats to China’s national security, the focus of war preparation, and the center of China’s expanding interests are all found “at sea.”12 This assessment has required the entire Chinese military to reorient itself to fighting wars in the maritime domain.

The PLAN has responded to these demand signals with great alacrity. Orders for new classes of advanced destroyers, frigates, corvettes, and auxiliaries have kept Chinese shipyards on a near wartime footing. In his speech, however, Admiral Shen did not highlight the need for new ships. Instead, he called for the service to develop technologies required to conduct “intelligent warfare.”

As the name implies, intelligent warfare relies on machines to take over many of the tasks formerly performed by humans. Artificial intelligence (AI) sits at its heart. AI enables machines to analyze data and draw conclusions with a degree of sophistication that rivals human intelligence. AI is valuable not only because it offers the potential for better and faster decisions, but also because it relegates lower-order decisions to machines, thereby releasing humans to focus on more important tasks. Autonomous vehicles—surface, air, and subsurface—operate at the vanguard of AI’s entry into the modern battlefield.

In his speech, Admiral Shen declared that intelligent warfare had moved from theory to reality. This presents a huge challenge for China, whose most dangerous potential foe is the United States—the country that invented intelligent warfare. Chinese analysts have fixated on the United States’ Third Offset Strategy, which they interpret as an effort to maintain overwhelming advantage against other great powers in this new form of warfare.13 The PLAN has closely watched the entry of unmanned systems into the maritime domain. Of special concern are platforms such as the U.S. Navy’s Sea Hunter unmanned surface vessel, which will be used in undersea warfare—a traditional PLAN weakness.14 When operational, the Sea Hunter (and vehicles like it) will be able to track China’s quietest submarines over long periods, unencumbered by the needs, wants, and frailties of a human crew.

China aspires not merely to catch up with the United States in intelligent warfare. Admiral Shen urged the PLAN to take advantage of the “historic opportunities” presented by AI. Indeed, Chinese military leaders see the AI revolution as a historic moment to surpass the U.S. military. They compare the advent of AI to a corner on a racetrack, where bold and skillful drivers—like China—can take the lead from the front-runner.15

Known Unknowns

In sum, to PLAN strategists a “world-class” navy is a sea control navy with global reach. These attributes are important enough that Chinese leaders intend to develop them with the utmost urgency. Given Washington’s many disagreements with Beijing, the Chinese program should spark alarm among U.S. policymakers. It also should provoke further questions.

What will be the nature of the PLAN’s global influence? Naval diplomacy has coercive and cooperative elements. Depending on the circumstances, warships can communicate the goodwill of a nation or its resolve to shed blood to get its way. China employs both forms along its maritime periphery. However, when Admiral Shen says China does not send its navy overseas to coerce foreign states, there is little evidence to dispute him. But this could change. Xi Jinping is on record complaining that when Chinese people and property face threats in foreign lands, China’s only option is to evacuate its citizens.16 At present, it lacks the ability to do more. Building the PLAN into a world-class navy will give Chinese leaders many new options. How will they use them?

To what extent is command of the sea a PLAN priority outside maritime East Asia? The answer to this question has a huge bearing on China’s long-term naval ambitions. Chinese military leaders frequently lament the vulnerability of major sea lanes across the Indian Ocean, the “lifelines” connecting China with resources and markets in the Middle East, Europe, and Africa. Sending naval task forces to counter Somali pirates in the Gulf of Aden is, at least in part, driven by a desire to safeguard Chinese use of this great saltwater highway. However, China also is very conscious that other great powers could menace its use of these sea lanes during a war or crisis. If Chinese leaders are truly committed to confronting these threats, it would require significant sea control capabilities west of Malacca. That, in turn, would demand a far larger and more capable naval force in the Indian Ocean than China currently possesses.

How do we square Admiral Shen’s emphasis on speed with the formal timeline for achieving world-class status? Officially, the PLAN has been charged with becoming a world-class navy by midcentury. That hardly reflects the urgency demanded by China’s civilian leaders. Assuming both goals are sincere, the only way to reconcile them is to conclude that Beijing intends two or three more decades of rapid naval modernization to achieve the global influence and sea control capabilities it thinks it needs. This insight prompts the most important question of all: Is the U.S. Navy’s own modernization program ambitious enough to counter a “world-class” PLAN?

1. Shen Jinlong, “Thoroughly Implement the Spirit of the 19th Party Congress, Plan and Promote Transformational Construction for the Navy in the New Era,” People’s Navy, 13 December 2017, 1−2. Shen’s December 2017 speech was given to an internal audience of PLAN admirals and published in People’s Navy, a print newspaper not readily available outside the Chinese navy. Therefore, it is a far more candid expression of PLAN intentions than speeches and articles disseminated for wider readership.

2. PLAN Party Committee, “Strive to Comprehensively Build the PLAN into a World-class Navy,” Qiushi, 31 April 2018, www.qstheory.cn/dukan/qs/2018-05/31/c_1122897922.htm.

3. Zhu Ning and Li Yibao, “The Sea Is Vast and the Heavens Are High for Galloping—The Gulf of Aden’s Unique Meteorology and Sea Conditions Are Good Conditions for Training,” People’s Navy, 13 March 2010, 2.

4. China’s Military Strategy, The State Council Information Office of the PRC, May 2015.

5. Yu Wenbing, “Taking Advantage of the Situation to Build a First-Rate Command Academy,” People’s Navy, 13 July 2018, 3.

6. Li Qihu, “Do Not Forget Your Original Spirit, Re-Create Glory: Sonar Technology Boosts the Dream of Becoming a Maritime Power,” Bulletin of Chinese Academy of Sciences no. 3 (2019): 258.

7. Liu Huaqing, Liu Huaqing Memoirs (Beijing: PLA, 2004), 438.

8. Li Jixiang, “Finding a Position from Which to Exert Effects in the Context of the Navy’s Transformative Construction,” People’s Navy, 19 December 2017, 3.

9. Andrew Scobell, David Lai, and Roy Kamphausen, eds., Chinese Lessons from Other Peoples’ Wars (November 2011), https://ssi.armywarcollege.edu/pdffiles/PUB1090.pdf.

10. Liu Yijian, “China’s Future Naval Construction and Naval Strategy,” Strategy and Management no. 5 (1999): 97.

11. Li Xuanliang and Wu Dengfeng, “Xi Jinping Attends a Fleet Review in the South China Sea and Delivers Important Speech,” Xinhua, 12 April 2018, www.xinhuanet.com/mil/2018-04/12/c_129849403.htm.

12. Zhao Xin, “Strengthen Work on the ‘Four Antis,’ Build a Defensive Line in the Secret Struggle,” People’s Navy, 3 July 2017, 3.

13. Zuo Dengyuan and Gong Jia, “Modern Naval Combat Is Becoming Intelligent,” People’s Navy, 17 August 2018, 4.

14. Qian Dong, Zhao Jiang, Yang Yun, “Development Trend of Military UUVs (Part 2): A Review of U.S. Military Unmanned System Development Plan,”Journal of Unmanned Systems no. 2 (2017).

15. Zhao Ming, “Taking the Express Train of Military Intelligent Development,” PLA Daily, 14 November 2017, 7, www.81.cn/jfjbmap/content/2017-11/14/content_191788.htm.

16. Excerpts from Xi Jinping’s Discourse on Holistic National Security Concept (Beijing: Central Document Press, 2018), 218–19.