If Deng Xiaoping was China’s George Washington, Xi Jinping is China’s answer to Theodore Roosevelt. Investigating U.S. history could give a glimpse into Asia’s maritime future.

Washington and Deng were toolmakers. They were founders who inaugurated ages of economic development on the home front. They wanted their nations to amass wealth, not just to bolster prosperity as something worthwhile in its own right, but to fund ambitious foreign policies when the time came. They knew it takes time and safe surroundings to build a foundry for national power and turn out the requisite economic, diplomatic, and military power implements.

In short, the founders counseled patience and self-restraint. To provide their nations a safe space, Washington and Deng shunned alliances that might entangle the United States or China in war, and they counseled posterity to do the same—until the time was right. Their logic: only after a rising power makes itself strong should it go abroad looking for monsters to slay. This is sound strategy.

If Washington and Deng were strategic toolmakers, Roosevelt and Xi were wielders of the implements the founding generations had fashioned. Each considered sea power the long arm of foreign policy, each oversaw a great navy, and each launched his nation into an outward-facing, muscular, saltwater brand of diplomacy. Roosevelt occupied the Oval Office from 1901–09 after a varied public-service career that included a term as Assistant Secretary of the Navy (1897–98). During an 1897 address at the Naval War College, Roosevelt reminded naval officers that President Washington had not espoused perpetual isolationism. Rather, Washington advocated for a spell of disentanglement to construct infrastructure and industrial might.

Afterward, Americans would enjoy the option to “choose peace or war, as our interest, guided by justice, shall counsel,” as Washington’s 1796 “Farewell Address” puts it. Roosevelt proclaimed the country should begin to exercise that option, making the United States a force to be reckoned with—not just in the New World but in the Old.

Roosevelt acted on his own advice as president. He fretted that Europeans might obtain naval bases in the Caribbean Sea, athwart the approaches to the Panama Canal then building. So he asserted an “international police power” intended to keep European empires from encroaching on the sovereignty of fragile Latin American states. The president mediated peace between Russia and Japan to end the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05). And he dispatched the Navy’s battle fleet, the “Great White Fleet,” on a round-the-world voyage meant in large part to deter imperial Japan from making mischief in the Western Pacific.

Roosevelt, in short, claimed to remain true to founding traditions. But his America was no longer Washington’s standoffish one of a century before.

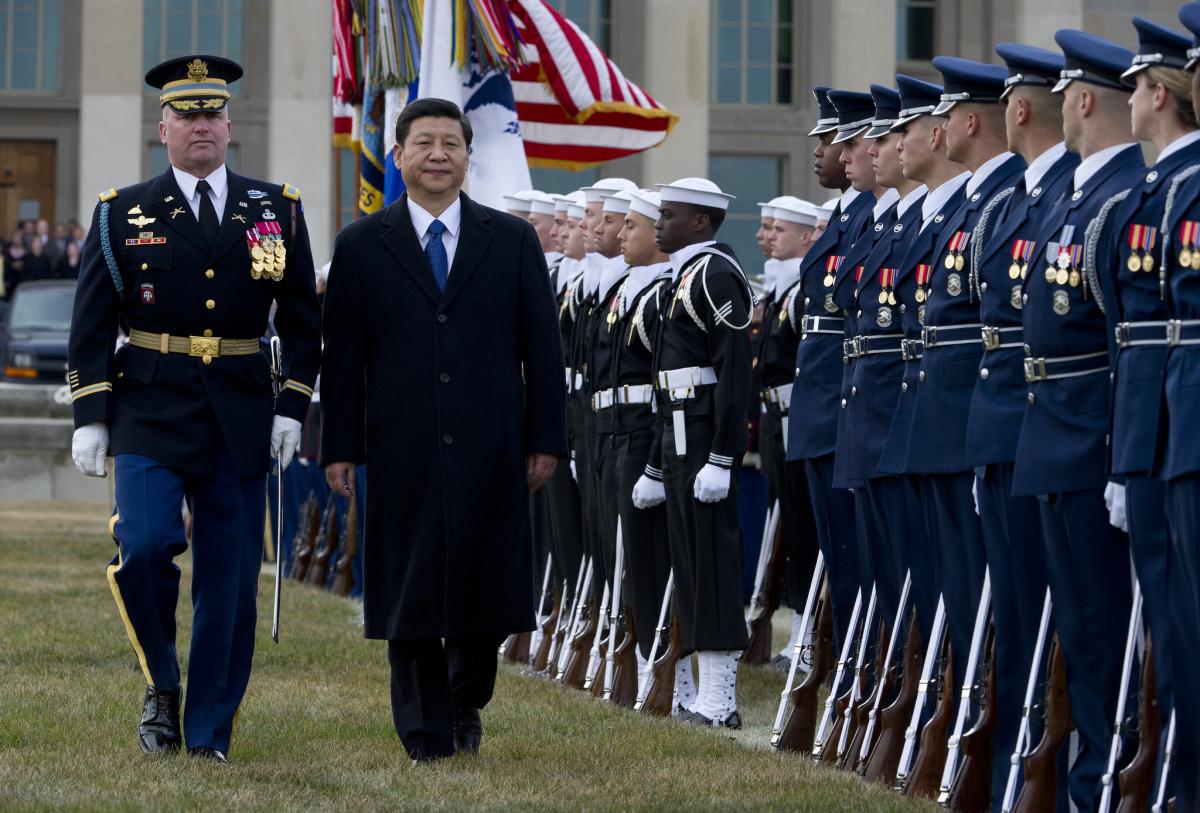

Similarly, Xi Jinping has launched Communist China into an assertive foreign policy aimed at fulfilling what he calls “China’s Dream” of national regeneration and grandeur. Back in 1990, Deng Xiaoping counseled party chieftains to “bide [their] time” until China was powerful enough to assert itself without undue peril. Xi came to power in 2012, convinced that Beijing had bided its time long enough. The new supremo set about concentrating absolute control of the diplomatic and military apparatus in his hands. He put that apparatus to work in the China seas and Taiwan Strait while augmenting the defensive and offensive power of the People’s Liberation Army Navy (PLAN), along with shore-based arms of seapower such as the PLA Rocket Force and Air Force.

Like Theodore Roosevelt, Xi Jinping ushered his country out of self-imposed seclusion. Like TR, Xi is pursuing a project that is nautical in outlook. Seaborne trade and commerce are integral to China’s Dream, just as fin de siècle Americans took to the oceans in search of foreign markets. Like Roosevelt, Xi views the navy as the mercantile fleet’s protector as well as the chief executor of foreign policy. And, like TR, Xi regards the battle fleet as interdependent with land-based defenses. Roosevelt maintained that coastal gunnery should guard American shorelines from attack, operating in conjunction with light, torpedo-armed craft such as submarines and destroyers. The U.S. Navy battle fleet would be “footloose” if the scheme worked, roaming the high seas wherever U.S. political leaders wished.

Xi’s PLA likewise envisions defending Chinese seacoasts primarily with land-based missiles and warplanes, fighting in concert with missile-toting diesel subs and surface patrol craft. Defenders can mount an “active defense” in keeping with strategic traditions dating to the founding of the People’s Republic of China in 1949 and before. Once shore-based defenses mature sufficiently, boosting senior commanders’ comfort level, the PLAN’s battle fleet, too, can make itself footloose. Chinese warships are now a common sight in the Indian Ocean—sometimes even farther afield.

TR had his Great White Fleet; Xi has his Great Red Fleet.

The parallels between America then and China today constitute more than a historical curiosity. The United States took a patient, methodical approach to diplomacy and domestic affairs, transforming itself from the agrarian republic of Washington’s day into the regional and global power of Roosevelt’s.

Studying its rise informs. Two immediate points stand out. First, if the 19th-century United States took a leisurely approach to national development, haste is Communist China’s watchword. Over a century elapsed between the time of Washington’s Farewell Address, when the founding president beseeched his countrymen to keep a low profile, and the time Roosevelt sent forth the battle fleet on its world cruise. It has been a mere three decades since Deng Xiaoping instructed his comrades to bide their time until ready.

China is in a hurry where America was not. The helter-skelter velocity of China’s rise may make a difference in how Beijing comports itself in Asian and world affairs. It is worth asking whether Xi will send the PLAN fleet on a grand tour reminiscent of the Great White Fleet’s—and for similar reasons.

And second, the United States fought a “splendid little war”—the Spanish-American War (1898)—to expel a decaying European empire from America’s near seas and certify its status as the regional strongman. It wrested Cuba, Puerto Rico, and other islands from Spain—extending its forward defenses into the Caribbean Sea and Gulf of Mexico, consolidating control over sea lanes that would one day lead to the Panama Canal, and entrenching itself in the Philippine Islands, adjoining the Asian mainland. One wonders whether China’s communist leaders might someday see fit to fight a splendid little war of its own, in an effort to oust what Beijing regards as a U.S. empire from the Western Pacific and announce its arrival as Asia’s regional strongman.

Communist China has never been a republic, agrarian or otherwise. In that sense it is unlike the early United States. And yet: to glimpse China’s future, study America’s past.