Alexander Hamilton founded the Revenue Cutter Service, which later became the U.S. Coast Guard, on the concept that well-planned and strategically deployed force packages would provide an outstanding return on investment. Hamilton envisioned that several strategically placed assets monitoring vessel traffic and enforcing tariff collection would provide funds for the growth of the fledgling nation. While the Coast Guard no longer collects tariffs, its cutters still serve a critical economic role by facilitating commerce, protecting mariners, and enforcing laws within the nation’s waters. However, as technology continues to advance, fully staffed vessels no longer are the most effective “sentinels of the laws.” Instead, fixed, passive acoustic monitoring using strategic underwater microphones and autonomous vessels must be used to make intelligence-driven decisions and effectively complete Coast Guard missions.

There are two types of underwater acoustic monitoring—passive and active. Active acoustic monitoring generates sound and analyzes its echoes. Conversely, passive acoustic monitoring relies on sensitive underwater microphones, called hydrophones, to listen for and analyze noise without producing any. The U.S. Navy pioneered passive acoustic monitoring during World War II and deployed it during the Cold War using its sound surveillance system (SoSuS). By strategically positioning a series of offshore hydrophone arrays, the Navy was able to (secretly) track Soviet submarines during the Cold War. When an unknown vessel was heard, each hydrophone array would provide a bearing to the sound’s source, allowing the Navy to triangulate the position. Analysts would then correlate the contact’s position with reports from various intelligence sources, and dispatch patrol assets or aircraft for further investigation if needed. This system extended beyond submarines: In 1961, the Navy successfully tracked the USS George Washington (SSBN-598) during her transoceanic voyage from the United States to the United Kingdom, demonstrating the ability to acoustically track vessels over global distances.

While the Navy mastered passive acoustic monitoring, the Coast Guard honed proficiency in active acoustic monitoring during World War II. On 9 May 1942, a sonar technician on board the USCGC Icarus (WPC-110) detected a German U-boat off the Carolina coast. Using her acoustic equipment, the cutter vectored in on the adversary, deploying depth charges and forcing the submarine to surface. The cutter rammed the U-boat, sinking the vessel and capturing 35 Germans. Three years later, in May 1945, the Coast Guard-manned frigate USS Moberly (PF-63) worked alongside the USS Atherton (DE-169) to track and sink a German U-Boat off the Connecticut coast. Once again, active sonar equipment installed on board the vessel made the successful engagement possible. The Coast Guard’s commitment to active maritime acoustic monitoring continued during the 1960s when 12 Hamilton-class 378’ cutters were built, each with the equipment to locate and track Soviet submarines. The Coast Guard’s successful use of active acoustic monitoring during World War II, combined with the Navy’s highly-successful SoSuS program during the Cold War, highlights the potential of today’s Coast Guard implementing passive acoustic monitoring.

The Coast Guard already is using passive acoustic monitoring to autonomously detect critically endangered North Atlantic right whales and notify nearby mariners. Despite the program’s success, it has not expanded beyond the single Coast Guard facility in Woods Hole, Massachusetts. Leveraging this remote-sensing ability would allow the Coast Guard to reduce its reliance on expensive aircraft patrol hours while providing the same level of service:

- Vessels fishing illegally in protected areas could be detected and identified without an on-scene patrol asset.

- Semisubmersibles, notorious for stealthily smuggling contraband from South America, could be detected far offshore.

- Rescue 21, the system used to generate search patterns by estimating distressed mariners’ positions based on radio calls, could be augmented to improve position accuracy.

- The International Ice Patrol, founded in 1914 following the sinking of the RMS Titanic two years earlier, monitors iceberg movement in the North Atlantic. Recent studies have shown that passive acoustic monitoring can detect icebergs calving into the sea.

Despite practical and economic applications, the Coast Guard has moved away from acoustic technology in recent decades. In 1992, the service disestablished the sonar technician rate and removed all submarine-detection equipment from its Hamilton-class cutters.A series of experiments supported by the Navy, Coast Guard, and National Marine Fisheries Service were conducted from 1992 to 1995 that explored the possibility of using SoSuS to track vessels fishing illegally. The experiment was a resounding success—results showed that SoSuS could be used to detect, identify, and monitor individual driftnet and trawling fishing vessels in the Bering Sea and northern Pacific Ocean. Despite promising results, the service failed to move to an acoustic-based enforcement approach.

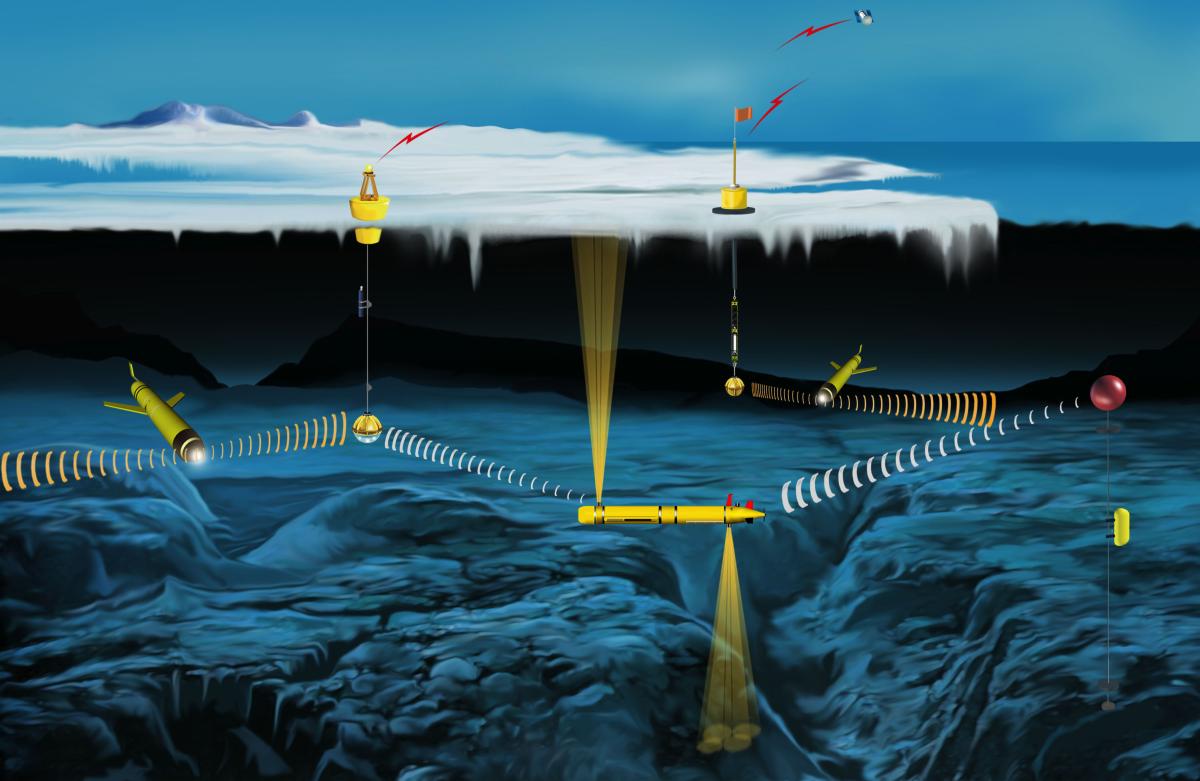

While a complete overhaul of Coast Guard operations to incorporate acoustic monitoring is impractical, several options exist to put Coast Guard–led passive acoustic monitoring to the test. Attaching hydrophone arrays to navigational and weather buoys is a low-risk first step. NOAA weather buoys, maintained by the Coast Guard, continuously collect and transmit atmospheric and oceanic data; installing an additional sensor during routine maintenance to transmit acoustic data is possibly a low-cost, high-impact solution. Furthermore, the Navy continues to maintain several legacy SoSuS arrays in operational or standby status, with three shoreside facilities to process the acoustic data. A joint endeavor between the Navy and Coast Guard to revive acoustic monitoring could enhance maritime domain awareness. The Coast Guard also could employ towed acoustic arrays; Coast Guard cutters towing an array of hydrophones as they patrol or transit, similar to the Navy’s current Surveillance Towed Array Sensor System, would provide the ability to track surface and subsurface vessels in a manner similar to SoSuS. Finally, the capability of low-cost autonomous vessels, such as undersea wave gliders, could enable passive acoustic collections on a global scale at a fraction of the cost of fully staffed multimission cutters, making this a worthy investment for the service.

Alexander Hamilton founded the Revenue Cutter Service on the idea that a few strategically placed assets could provide real benefits to a fledgling nation. In today’s intelligence-driven Coast Guard, employing strategically placed underwater acoustic sensors could provide real benefits, inform the service’s decisions, and act as a force-multiplier to complete Coast Guard missions. Just as the Navy’s implementation of SoSuS during World War II aided the war effort and supported the nation, the Coast Guard’s implementation of acoustic monitoring would aid in executing its 11 statutory missions.