Moments before the torpedo exploded in a deafening geyser of deadly fury, Captain Charles Prior and his crew of the SS Black Point were thinking only of how soon they would get into Boston and how grateful they were the war in Europe was ending. They could not have imagined that 12 of the 46 men on board were about to die.

The formal signing of Germany's surrender at Reims, France, on 7 May 1945 was only 48 hours away. Grand Admiral Karl Dönitz, presently in command in Germany following Adolf Hitler's suicide, issued a radio communiqué on 5 May, calling on all U-boats to cease offensive operations at 0800 (German time) the next morning and return to home ports. "VE Day" would soon end years of horror and sacrifice—but not quite yet.

Target: Black Point

Around 1700 on 5 May, only four miles off the coast of Rhode Island and in sight of Point Judith, 24-year-old Lieutenant (junior grade) Helmut Frömsdorf, commander of U-853, began working out his underwater attack solution. At periscope depth, he lined up his boat on the 5,000-ton collier Black Point as she slowly made her way into the western end of Rhode Island Sound. The unsuspecting ship was on the last leg of a journey up through the safety of the coastal waterway from Norfolk, Virginia, with thousands of tons of coal in her hold. She left her protective convoy while passing New York Harbor and, unescorted, was not even zigzagging in these presumably friendly waters.

U-853, with a crew of 54, had sortied out of Stavenger, Norway, on 24 February 1945, reaching the U.S. East Coast in late April. She was a type IXC/40 snorkel boat. Whether Frömsdorf never heard Dönitz' cease-fire call or chose to ignore it will never be known. Nor can we know why he took such a chance so close to a defended shore.

At 1740 that afternoon, U-853 opened torpedo fire. Seconds later, a full 40 feet of the Black Point's stern was completely blown off into the sea. At the Point Judith Coast Guard Station, Boatswain's Mate Joe Burbine, on watch at the time, saw the Black Point in his binoculars just as he heard a muffled explosion and watched the ship stagger to a halt.

The torpedo hit the starboard side just aft of the engine room. Several of the victims were killed in the explosion, and the mortally stricken ship quickly began to fill and settle as Captain Prior gave the order to abandon ship. The collier rolled over 25 minutes later and went down by the stern, carrying the bodies of 12 crewmen with her. Captain Prior said later he never saw the torpedo, but the captain and first mate of the nearby Yugoslav freighter SS Kamen said they saw it—too late. The Kamen quickly sent out an SOS, alerting other ships to the presence of a hostile submarine while rescuing 34 men, including 4 wounded, who were taken to the Coast Guard station. The Black Point was the last sinking victim of a German U-boat in U.S. waters. And now, in the final combat of the war against Nazi Germany, the hunt for U-853 began.

On the Attack

At 1742 the Coast Guard-manned frigate Moberly (PF-63), 30 miles to the south, heard the SOS. This ship, along with the Navy destroyer escorts Amick (DE-168) and Atherton (DE-169), were part of Task Force 60.7, which had just delivered a convoy to New York and was now headed for Boston. Lieutenant Commander L. B. Tollaksen, commanding officer of the Moberly, was the senior officer present since the fourth warship, the destroyer Ericsson (DD-440), under Commander F. C. McCune, was by then far ahead in the western end of the Cape Cod Canal approaching Boston. Tollaksen turned north and steamed toward the site of the sinking at full speed.

For some unknown reason, Captain Frömsdorf, instead of departing the scene as quickly as possible, lingered in the area after his attack. For U-853, it was a fateful decision. It would be more than an hour and a half before the U.S. warships could get there, but even then the sub was still hugging the bottom only eight miles from where the Black Point went down. A total of 11 Navy and Coast Guard ships arrived about 1930 and immediately set up a barrier force while initiating a sweep search with echo ranging that started at the northern tip of Block Island. At 2014 the Atherton's pinging sonar suddenly registered an unusual echo. U-853 had been located near the bottom, moving on a course of 090 degrees.

Lieutenant Commander Lewis Iselin, skipper of the Atherton, barked out the orders. At 2029, the ship dropped 13 magnetic depth charges, one of which exploded. But no one could determine if it had hit the sub or one of the many wrecks on the ocean bottom in that area. A second attack run employed hedgehogs. The Atherton lost contact on that run because of the disturbed water condition in the 100-foot waters. As the crashing charges exploded around her, rocking the sub, Frömsdorf continued to move. The Atherton suspended her attack and tried to pinpoint the sub's new location. By this time, the Ericsson had arrived on the scene and Lieutenant Commander Tollaksen turned over command of the search to her skipper, Commander McCune.

Joining the Final Fight

Thousands of miles away at Reims, Colonel-General Alfred Jodl, representing the German military, was reluctantly preparing to sign his name the next day to the surrender document. But off southern New England, the last fight was just under way.

For the farmers, fishermen, and townsfolk of little Block Island, this latest eruption of naval action was not new. Sitting out in the ocean 12 miles off Rhode Island's southern coast the islanders had seen or heard numerous nearby engagements over the years against the deadly U-boat menace. In fact, the Navy had authorized a reconnaissance patrol made up of fishing boats from the island to report on the sightings of periscopes and surfacing U-boats. Such sightings were especially common in the first years of the war as enemy submarines prowled America's East Coast in killer Wolf Packs, sinking hundreds of thousands of tons of Allied shipping. Eight tall concrete lookout towers had been erected on Block Island to watch for enemy ships and planes.

On 25 May 1944 British warplanes had attacked U-853, then under Lieutenant Helmut Sommer, on the surface, but she got away. On 15 June that year, U.S. Navy aircraft and several destroyers caught her on the surface but she dived and escaped again. Two days later, two Wildcat aircraft from the American escort carrier Croatan (CVE-25) heard her radioing weather information back to Germany. They spotted her and attacked, killing two of her crew and wounding 12 others, including Captain Sommer, before he took the sub deep. By that time Navy seamen had given the elusive U-853 the nickname "Moby Dick," while the submarine's crew gave Captain Sommer his own moniker, "Der Seiltaenzer" ("The Tightrope Walker"). Damaged, the U-boat returned to Lorient, France, for refitting, repair, and crew replacement. Now, a year later, she was on her final patrol. But this time, Frömsdorf, Sommer's young, handsome, former second in command, was the new Kapitan.

Contact!

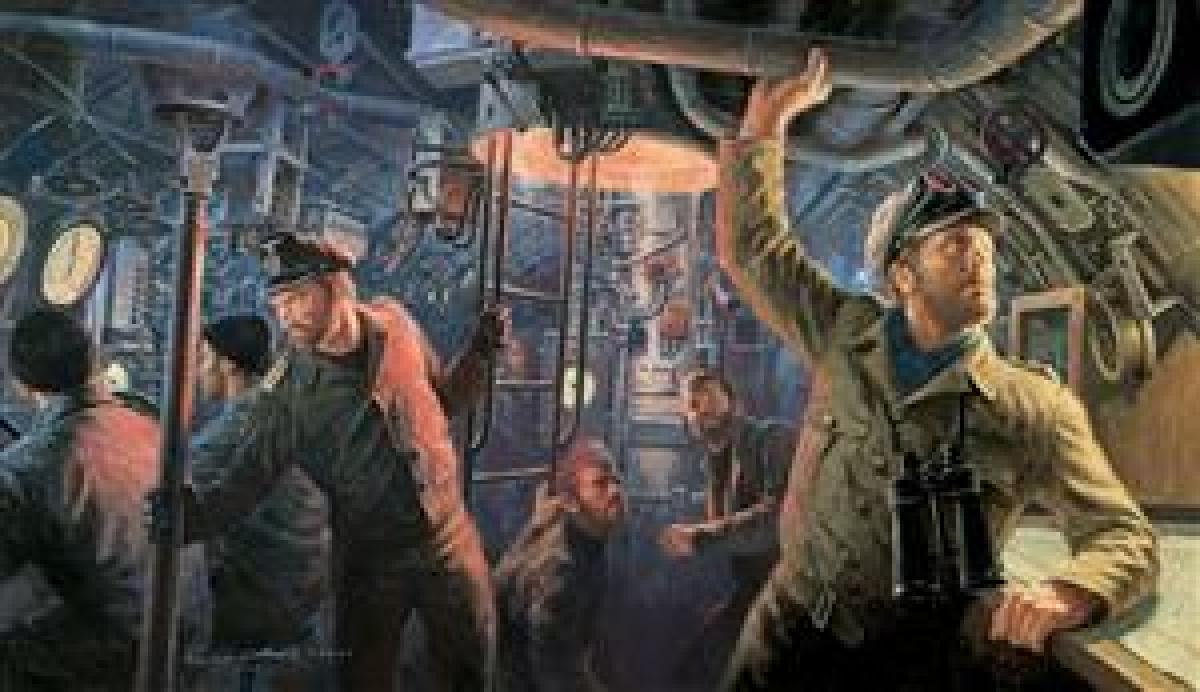

After assuming command of the U-boat hunt, Commander McCune ordered several smaller ships to maintain the barrier patrol while sending the Atherton searching to the north and the Moberly to the south. Finally, after several false alarms, at 2343 the Atherton's sonar relocated the target, believed to be 100 feet down, 4,000 yards east of her previous position, lying dead in the water with propellers silent. One can only imagine the scene inside the sub by this time. The temperature of the hot, fetid air would be going up. Light bulbs were broken, glass gauge faces were cracked, and leaks may have appeared. Movement and noise were kept to a minimum as Frömsdorf and the sweating crew waited in fear for the next jarring explosion. Moments later, it came, in another devastating hedgehog attack. And this time the attackers could see results. Bubbles of air and oil and pieces of broken wood rose to the surface. The Atherton circled for 20 minutes. U-853 was hit but holding, and Commander McCune ordered another attack to try and split the submarine's pressure hull. Again, air bubbles and oil rose to the surface, but now a pillow, a life jacket, and a small wooden flagstaff were also spotted.

Exploding depth charges in such shallow water knocked out the Atherton's dead-reckoning tracer, so the determined McCune ordered the Moberly to move in. Incredibly, the Moberly's sonar revealed the submarine was moving again. Captain Frömsdorf was cutting south across her course at a speed of four to five knots. McCune ordered another attack. Both the Atherton and Moberly were having sonar difficulties, but they soon determined the sub's speed had dropped to two or three knots. By this time, Frömsdorf and his cornered crew must have known the end was near.

At about 0200, the Moberly raced in over the target, dropping a concentrated hedgehog barrage. After that attack, U-853 stopped moving and appeared to have bottomed. Soon, in the faint light of dawn, American seamen could see heavy pools of oil rising to the surface. Escape lungs, life jackets, and other debris bobbed up as well. Moby Dick was apparently dead. Even so, McCune ordered more explosives dropped to break the sub apart.

Now came an unusual moment in this already unlikely battle. At about 0600, two Navy blimps (K-16 and K-58) from Lakehurst, New Jersey, arrived on the scene to photograph the area, fix the sub's position with smoke and dye markers, and drop a sonobuoy to pick up any underwater sounds. Sonar operators on both blimps reported what they described as "a rhythmic hammering on a metal surface which was interrupted periodically." They said the hammering sound was then lost in the engine noise of the last attacking ships. The Navy has never officially commented on the possible source of that sound.

At 1230, McCune sent most of his ships on to Boston, while a diver from the USS Penguin (ASR-12) went down to attach a line to the sub. He landed on the conning tower and reported the sub's side split open with bodies strewn about inside. It was all over.

Despite wishful stories and rumors on Block Island, no secret treasure or any other valuable cargo was on board. In Old Harbor, fishermen gathered to talk about the end of the war and this last battle so close to their shore. In the shack of fish buyer Henry Heinz, one grizzled gentleman sitting by the coal stove remarked, "If you ask me, the damned Heinie sold out cheap . . . for a coal hod!"

Moby Dick is Dead

By this time, of course, the war was ending. The surrender document was signed, and Lieutenant (junior grade) Helmut Frömsdorf had wasted a total of 66 men's lives in a senseless, final, violent act in a war that had already recorded a new level of horror and violence. In the years that followed, divers made numerous trips down to U-853.

In 1960, one body was removed and buried with full military honors in Newport, Rhode Island, in ceremonies attended by officials from West Germany, the German consul general from Boston, and U.S. Navy representatives. The twin screws from U-853 went on display a few miles from the Island Cemetery Annex in Newport. Moby Dick still lies where she died, 127 feet down, covered with barnacles, slowly rusting away. And each year, swimmers and sunbathers gather on the nearby Block Island beaches, while pleasure boats filled with unsuspecting, laughing vacationers cruise right over her silent tomb.

U-853's Second BattleFifteen years after the U.S. Navy blasted apart U-853 on the bottom of the sea, a new fight broke out over one man's determined plan to raise the submarine. Throughout 1960, newspapers in Providence and Newport, Rhode Island, were filled with stories about more and more divers visiting the sub. Gruesome details included sightings of skeletons lying about the interior. In October, an idea to raise U-853 was advanced, and immediately a heated public discussion ensued.Burton Mason, head of Submarine Research Associates in Trumbell, Connecticut, told anyone who would listen that despite criticism, he was going ahead with his controversial plan to raise the U-boat and prepare her for public display. In January 1961, the city council of Newport, with the backing of a group of clergymen from that city, proposed taking action to prevent what it called "desecration" of the sub and the remains of her 54 crewmen. Incredibly, the summer before, Mason had removed the body of one crewman whose remains were buried with full military honors in the Island Cemetery Annex at Newport on 24 October 1960. In attendance at that unusual ceremony were Dr. Guenther Motz, German consul general in Boston; Commander Bertholdt Jung of the German Navy and his wife; Captain Charles Cook, chief of staff of the Newport Naval Base; and assorted other government and naval officials. The state of Rhode Island warned Mason that although U-853 did appear to be in international waters, Rhode Island would fight any effort to violate what it called its "tidal Waters." However, Mason cited earlier rulings from the U.S. State Department and the Coast Guard that the sub "lies in the high seas and not in U.S. territorial waters" and declared salvage operations, with Swiss and German divers, would begin in April, with the raising to be completed in June or July. At this point, the West German government in Bonn released a diplomatic preemptive strike. On 18 January 1961 it announced that U-853 "is still owned by Germany and any action to surface the vessel or bring anything up from it is illegal." The Bonn statement also declared that "raising the sub would be akin to piracy." Mason's reply was one of defiance. He blustered: "We're going right ahead! Whatever thunder they want to throw, let them throw it!" However, spring and summer came and went, and no sub-raising flotilla materialized. Either a lack of financing or concern over triggering a real international battle, or both, may have been more than Burton Mason could handle. For whatever reason, no attempt has ever been made to remove U-853 from her watery grave. —Adam Lynch |

Sources:

ENS D. M. Tollaksen, USN, "Last Chance for U-853," U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings, December 1960.

Michael Maynard, "The Secret of Point Judith," Sea Classics, Spring 1983.

Walter Schroder, Defenses of Narragansett Bay in World War II (East Greenwich, RI: Minuteman Press, 1980).

Thomas Reach and Elliot Subervi, "The Twisted Fate of U-853," Skin Diver, March 1974.

Robert Frederiksen, "The Killing of U-853," Providence Journal, December 1961.

"Point Judith Sub Reported Sunk," Newport Daily News, 6 May 1945.

"Nazis Sink Collier Near Pt. Judith," Newport Daily News, 6 May 1945.

"Now It Can Be Told," Providence Evening Bulletin, 17 May 1945.

"U-boat Sinking Off R.I.," Newport Daily News, 17 May 1945.

Robet Downie, Block Island—The Land (Block Island, RI: Book Nook Press, 1999).

Paul Kemp, U-boats Destroyed: German Submarine Losses in the World Wars (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997).