The mine warfare field (pun intended) has the largest mismatch between requirements and capabilities of all the warfare areas, and the gap is widening. The problem is not a lack of technology and good ideas, but a lack of commitment. The surface community is quick to complain about the mine threat but it is letting its mine countermeasure ships degrade without a clear path to replacing their capabilities. The Air Force is happy to use research-and-development money to explore sowing sea mines from stand-off aircraft (Quickstrike) and removing shallow-water minefields with the joint direct attack munition (JDAM) assault breaching system (JABS), but it is unlikely to acquire or prioritize the resources to accomplish these missions. The Marines are quick to add JABS to their plans, but they are not doing anything to support or resource the system. The Naval Expeditionary Combat Command has some interesting shallow-water systems, but in the Far East, they are stuck in Guam because their Mark VI patrol boats do not have the legs to go anywhere they might be useful.

The services and warfare communities are ignoring the mine threat and mining opportunities because it is easier to blame another service than to perform this difficult and unglamorous but very important task. The answer is to give accountability to those who will benefit from the capability and overcome technical and prioritization issues.

U.S. Navy courtesy of Lockheed Martin

Littoral and Open-Water Mine Countermeasures

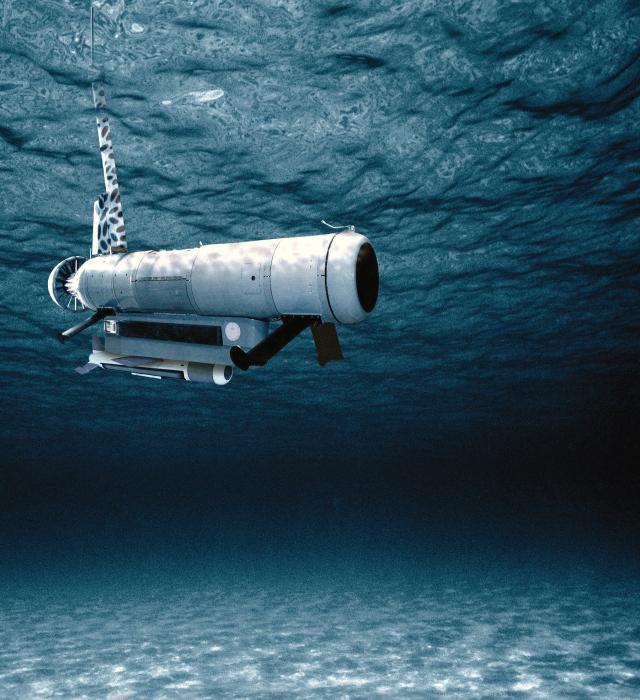

The surface community had a mine countermeasure plan, the Remote Minehunting System (RMS). It put all its eggs in that basket and then did not fix the one limitation to making it operational—the remote minehunting vehicle (RMV). The RMV was to launch from destroyers and littoral combat ships (LCSs). On LCSs, combined with mine-destruction and removal systems and personnel, RMVs were meant not only to replace mine countermeasure ships, but also to provide even more capability. It was envisioned that each destroyer would have two RMVs as the search and mapping portion of the RMS. The commanding officer of the USS Bainbridge (DDG-96) even wrote a positive Proceedings article about their 2007 trial deployment with the RMS.1

The main body of the system looks like a large, fat torpedo and houses the diesel engine and a forward-looking sonar to search for surface mines and moored mines close to the surface. In addition, a variable-depth towed body has additional forward and side-scan sonars to search for bottom and more deeply moored mines. The snorkel not only provides a way for the engine to breathe, but also has antennas that enable precise navigation and accurate mapping and mine-location data. These autonomous, semisubmersible minehunting vehicles could be sent ahead through choke points and into harbors. At one time, the RMV was even an outstanding candidate to investigate locations where diesel submarines might be waiting in ambush.

However, the RMV’s diesel engine air intake was ingesting water, which would shut down the diesel and cause the semisubmersible to bob to the surface, where it would need to be recovered, likely in the middle of a mine-danger area. Unfortunately, the RMV was the only search system for the LCS mine warfare mission module. Its failure left the Navy with no LCS mine countermeasure mission module or destroyer presearch capability, MCMs well past their prime and too few in number, and no clear path for the mine countermeasures community to develop the capabilities to keep the sea lanes, choke points, and harbors open.

The RMV’s propulsion issue should have been overcome. The ability to control its buoyancy in the real-world condition of random waves was discovered early in testing, but the inflexibility of the Navy procurement system was as much of an impediment to providing the required capability as the waves. When the Soviets were having problems keeping the ramjet of their antiship missile, the SSN-22 Sunburn, from flaming out in flight, they added the ability to restart the engine a few times so that it could cover the required distance. This solution could have been applied to the RMV to allow it to purge the water from its diesel engine and restart.

The Navy also could have developed an all-electric or air-independent version in place of the diesel engine. A different engine likely would have cost more and resulted either in less endurance or a larger system not exactly in accordance with the program of record, but it was a solution that could and should have been executed.

Sowing and Destroying Shallow-Water MineFields

U.S. Marine Corps

Quickstrike and JABS are two applications of the same technology. Both use the JDAM guidance system either to precisely place mines from aircraft (Quickstrike) or to drop a large number of precisely spaced 2,000-pound bombs to punch lanes through a shallow-water minefield so amphibious connectors (JABS) can get ashore. Quickstrike mines may also employ the JDAM-ER wing kits to give them a significant stand-off range. The same can and should be done for the JABS munitions to give more flexibility to the employing aircraft and protection packages that support them. Dropping from outside the air-defense threat area eases the suppression of enemy air defense (SEAD) requirements and may free fighter, bomber, electronic attack, and tanking assets for other missions. In addition, it would simplify the command, control, and coordination of aircraft employing the JABS munitions. While Quickstrike and JABS do not have the technical problems of the RMS, they do have scarcity and priority issues.

Quickstrike likely would be used offensively to mine the entrances of enemy harbors to deny adversaries the ability to put their forces to sea or return for resupply and maintenance. Trapping an enemy navy in port is a great idea, but mining its harbors is an act of war. If the United States is not going to offensively mine before a war begins (thus starting a war), it probably will not mine soon after, because the adversary’s navy likely will already be at sea and U.S. aircraft will be busy supporting the fight. In addition, there is a significant time penalty involved in the reconfiguration of bomber bays to drop mines instead of bombs. Therefore, if the United States wants to offensively mine, it needs either to procure more aircraft or to reprioritize the ones it has.

Combat power ashore cannot be built fast enough or sustained with vertical lift alone, so a clear path to shore is imperative for the success of amphibious operations and many land component operations. JABS likely will have the same aircraft availability issues as Quickstrike, compounded by a probable munitions issue. Two-thousand-pound precision-guided bombs are in high demand in war, so unless the United States is starting a war with an amphibious assault, it is unlikely there will be several hundred spare 2,000-pound bomb bodies and JDAM guidance kits available, not to mention the large number of bombers and fighters required for such a simultaneous strike.

While the assault lanes technically could be blasted over an extended period with smaller strikes, once (loudly) clearing the minefield, the element of surprise is lost and the window of opportunity begins to close. The use of traditional manned and unmanned minehunting, -sweeping, and -neutralization systems also would be time consuming and give away the game. Quickly carving amphibious lanes is the only path to success, and JABS is the only proven technology with that capability.

However, there may be an alternative to JABS in the not-too-distant future. There is ongoing experimentation with crab-like small unmanned vehicles that can swim and walk in shallow water, the surf zone, and even on the beach.2 These small systems would find and attach themselves to mines before detonating a charge to destroy the mine. They would be launched from aircraft or boats in large numbers and waves to clear a path ashore. The concept looks promising, and if it becomes operational could clear a path with a few cargo planes or several helicopters supported by a SEAD package—instead of dozens of heavy bombers.

Neither should cargo planes and heavy lift helicopters be excluded from the Quickstrike and JABS mix. Why not roll mines and bombs equipped with JDAM guidance kits and JDAM-ER wings out the back and off the ramps like palletized cargo and vehicles? The guidance kits would provide a generous launch window and the wings a significant stand-off range, especially at higher altitudes. Every Marine expeditionary unit (MEU) air combat element is supposed to have 12 MV-22 medium-lift tilt-rotor aircraft and four CH-53E/K heavy-lift helicopters.3 Based on internal carrying weight capacity and munitions only being one-high so they can easily slide out the back of the cargo bay, each MV-22 should be able to carry and employ five Quickstrike munitions and each CH-53 possibly a dozen or so. This would give each MEU the organic capability to execute JABS in 100 munition increments.

Given that an amphibious assault likely would be conducted by three or more MEUs, 300 JABS munitions could be employed per deck cycle. If the two to four mine countermeasure helicopters, MH-53Es, operating from Lewis B. Puller–class afloat forward staging bases could add ten each per sortie and ground-based Marine, Air Force, and allied cargo aircraft such as C-130s and C-17s could add 10 to 20 munitions per sortie, the JABS burden could be removed from the Air Force bomber force.

The Way Ahead

In a future battle the United States will have to keep shipping lanes open, close those of its adversaries, and clear a path for Marines. This will involve joint-level learning and service-level commitment. The first step is to inject realistic enemy mining into war games. Initially, U.S. forces will have only the capabilities they currently possess. When the mine problem gets to the point that follow-on exercise training and certification objectives will be lost, the joint/combined forces commander will call a training time-out, and the required capability will be articulated and documented for follow-up at a “binding” post-exercise lessons-learned conference. Then the exercise will resume, because far more than mining is practiced during these events. The same procedure will be applied to offensive mining and amphibious lane-clearing portions of the exercise.

The importance of a binding lessons-learned system cannot be overstated. Unfortunately, lessons learned from wargames often are not captured, because inputs are due well before the end of the exercise, units feel obligated to submit slides, and units and staffs already are preparing for the next exercise, operation, or inspection before the exercise has concluded. Lessons-learned meetings and conferences are scheduled after exercises, but the cumbersome administrative format usually results either in dozens of inconsequential, mind-numbing slides or a handful of low-hanging fruit being picked instead of a focus on the most important issues. This is why there should be fewer exercises and more emphasis on learning what is required to succeed and how to correct deficiencies.

Lessons-learned conferences should include rehearsal of concept (ROC) drills in which component commanders (Army, Navy, Air Force, Marine Corps) in that theater brief the joint forces commander on how they will accomplish certain tasks and solve specific problems. When leaders have to personally brief an issue to their own superior it makes them accountable, and they are less likely to ignore a problem or provide an unworkable solution. To make corrective action more likely, National Command Authority and congressional Armed Services Committee members should have some representation at these lessons-learned ROC drills so appropriate funding decisions can be made and appropriate personnel promoted. Only by closing the learning loop will solutions to the hard problems such as mine warfare be developed and implemented.

1. Stephen Coughlin, “Modern-Day Minehunting Destroyer Style,” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings (June 2008).

2. UMDRobotics, “RoboCrab: A Horseshoe Crab Inspired Amphibious Robot for Righting in Surf Zones,” 23 March 2014.

3. LTGEN Ronald L. Bailey, USMC, “Policy for Marine Expeditionary Units (MEU),” 29 October 2015.