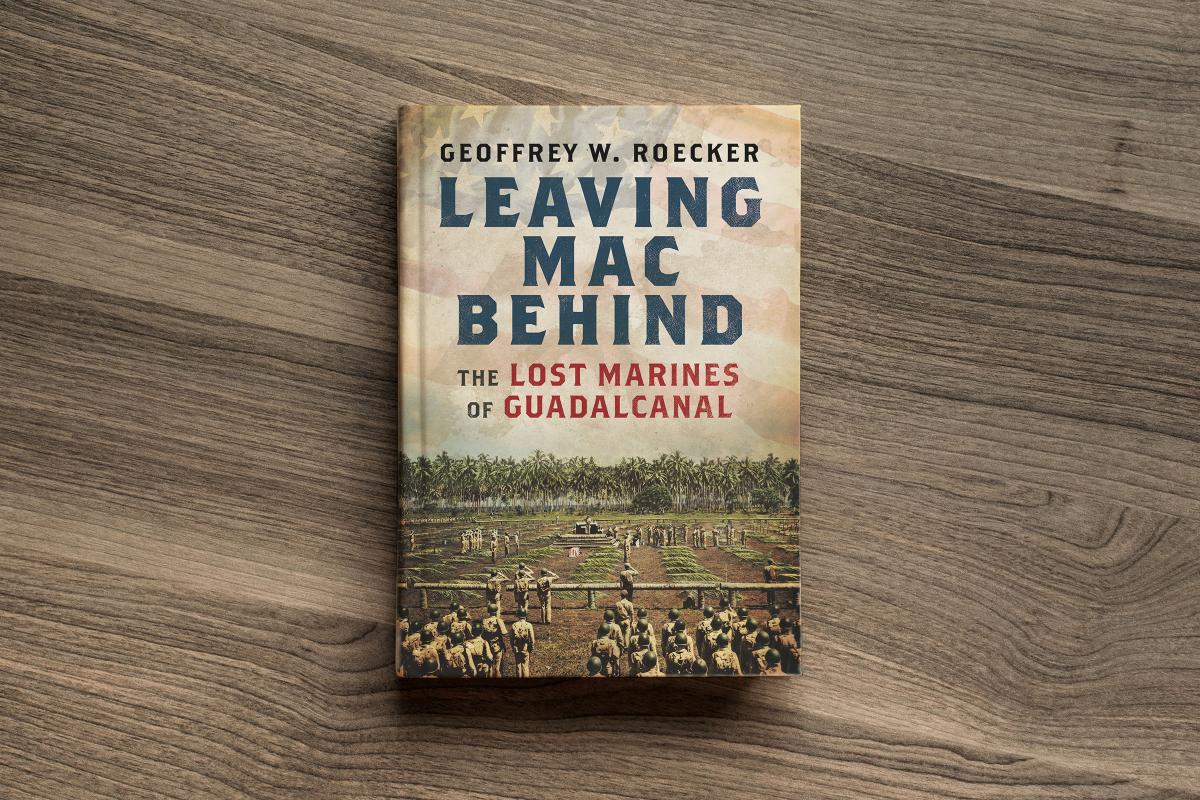

Leaving Mac Behind: The Lost Marines of Guadalcanal

Geoffrey Roecker. Charleston, SC: Casemate Publishers, 2019. 288 pp. Photos. Maps. $31.50.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Commander Andy Cox, U.S. Navy Reserve

As Geoffrey Roecker tells it in Leaving Mac Behind, the 1st Marine Division arrived on Guadalcanal in August 1942 with no practical knowledge on handling mass casualties, stemming in part from lean Depression-years budgets and the untested nature of amphibious warfare. General Alexander A. Vandegrift’s Marines made do with a series of blunt directives and administrative expectations for collecting, identifying, and burying the dead. But combat conditions overwhelmed these efforts, and so new procedures evolved out of necessity and expedience as the fallen piled up inside and outside the perimeter around Henderson Field.

Wartime Navy policy halted the shipping of remains back to the United States, making temporary overseas cemeteries and field burials necessary as soon as the first boots touched Guadalcanal sands. In those early, chaotic months of the Pacific war, Roecker shows how a human being, in death, became data in the knowledge bank of an institution unused to handling it: names removed from the muster rolls; coordinates recorded in the unit’s war diary; remains to be identified (or not); corpses interred in cemeteries, or fields, or lost in enemy territory. While the cost of designing better fighter aircraft or refining battle doctrine was paid in combat deaths, learning how to collect and account for the war dead with accuracy and grace came at the cost of losing some men altogether. More than 3,000 servicemen’s remains eventually were consolidated on Guadalcanal from many different cemeteries, field sites, and isolated graves around the Solomon Islands, but hundreds remained unidentified or left in the field.

Roecker says he wrote this book, “to provide some detail in the last days of a few Marines who have not yet been accounted for, and the ongoing efforts to bring them home.” Ongoing is the active word here; the latest entry for repatriated remains dates to 2017. He starts most chapters with a combat vignette of Marines struggling through the jungle, fighting a determined enemy, but his narrative is not about the battle. Rather, it is about a process that started with the aftermath of servicemens’ deaths and developed under strain and time. The book’s narrative can be jarring when it switches from combat to administrators and grave diggers grappling with a massive logistical problem, but Roecker vividly shows how much the chaplains, quartermasters, and recordkeepers who remained had to do after the war moved on. Roecker covers the tough, necessary work done, during and after the war, by those who checked records, searched for the missing, collected and identified remains, and interred them at the Army-Navy-Marine Corps Cemetery on Guadalcanal. Time, uncertainty, and danger worked against wartime recovery, and in the meantime bodies and landmarks were disfigured, destroyed, moved, or reclaimed by floodwaters and jungle growth. Gaps appeared in the historical record when units lost original documentation or relied on inaccurate sources. But the biggest obstacle to locating the fallen was the dearth of accurate maps. The Marines had terribly inaccurate maps of Guadalcanal for most of the campaign, owing in part to the early loss of almost all the 1D’s cartographers and intelligence officers.

Contemporary overlays and modern satellite imagery can do only so much against bad coordinates. Postwar attempts to recover bodies often failed for the same reasons, but the passage of time injected more confusion into records, memory, and the landscape.

The book closes by recounting multiple attempts by the military, government, and individuals to find the last missing Marines on Guadalcanal. Finding isolated graves and identifying remains after so long is nearly impossible, but every now and then someone finds another lost Marine, rekindling hopes in families still awaiting closure. These Marines are called “missing” or “not recovered” and thus are remembered only by survivors’ memories and names on memorials around the United States and Pacific island sites. Roecker’s book is a poignant, compelling reminder that every one of them still waits be returned home.

Lieutenant Commander Cox teaches history at the U.S. Naval Academy. He graduated from the Academy in 2005 and flew helicopters while deployed to the western Pacific.

Burn-In

P. W. Singer and August Cole. New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2020. 432 pp. Notes. $28.

Reviewed by A. Denis Clift

With their new novel, Burn-In, P. W. Singer and August Cole are building an increasingly noteworthy collection of futurist fiction pointing to possible realities—works viewed as “must read” by growing numbers inside the armed forces and beyond.

In parallel, following publication of their first techno-thriller, Ghost Fleet, Cole has joined with the Naval Institute both as an author and speaker. His article, “Arts & Artists Impact National Security,” appeared in the May 2016 Proceedings. He also was a keynote speaker on “Thinking the Unthinkable: How Fiction and Other Narratives Can Teach Us about Future Conflict” at the 2018 Institute–Naval Academy conference, “The New China Challenge.”

If you believe in “bots”—a revolutionary future based on advances in artificial intelligence guiding ever-increasing numbers of robots with evolving skill sets, responsibilities, and physiques—Burn-In is your book. The heroes are FBI Special Agent Lara Keegan, a former combat Marine E-5, and the five-foot-tall, human-form robot TAMS (Tactical Autonomous Mobility System), which she has been tasked with burning-in—determining whether it will be capable of the most challenging, deadly police work.

This is an age of increased terrorism in Washington. Keegan has just foiled a Union Station bombing attempt. As the agent/bot teamwork begins, she learns that TAMS’ vocal and physical responses to her spoken directions and teaching are right-on, with AI adjustments second nature. The robot negotiates the FBI agents’ obstacle course with speed and agility and moves through the hostage rescue team kill house taking down pop-up moving targets with dead-eye gunfire accuracy. Together, they move into action, ease their way out of nasty fixes, arrest armed robbers, and even leap from building-to-building early on, all monitored by the farseeing, multidimensional visglass/Watchlet AI technology of their FBI superiors.

On a summer’s afternoon, when Potomac floodgates are disrupted and a wall of water swamps downtown, D.C. Agent Keegan and TAMS are on it, leading a citizens’ effort to fill sandbags and save a treasury of documents in the National Archives. They are becoming a hero team. The FBI, wanting a big win, unleashes them on grim disruptions springing out of nowhere. Millions of Americans damn the new age of technology, damn the bots, the machines that have stolen their jobs, their money, and their futures. Conspiracy theories are tearing at the nation.

Keegan surveys each setting with her multidata, vibrant-projection, full-color night-vision visglasses and draws on TAMS’ bottomless access to precise information. Under heavy gunfire at an armed extremist compound, she sees a young boy, around 12, and a young girl, around 9, armed with AR-15 rifles exit the doorway: The boy raised his weapon halfway then let it drop, unable to shoot. But the girl brought the rifle all the way to her shoulder and aimed at Keegan’s head. Keegan froze. She couldn’t do it. Shouldn’t do it . . . Then came two blasts, and the children fell back into the dark of the pump house. Keegan pivoted to see TAMS behind her, its shotgun still in a firing position.

Singer and Cole challenge with their vivid writing. Is this fiction or future reality? Is this the incredible new AI canvas we are stepping into and must master if we are to survive and be meaningful, if we are to live and lead on this planet? As the plot thickens, I recommend Burn-In to you, the reader, live or bot.

Mr. Clift is the U.S. Naval Institute’s vice president for planning and operations and president emeritus of the National Intelligence University.

Neptune’s Laboratory: Fantasy, Fear and Science at Sea

Antony Adler. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2019. 256 pp. Images. Notes. Index. $39.95.

Reviewed by Don Walsh

Antony Adler is a historian by training, earning his doctorate at the University of Washington where one of the major U.S. oceanographic institutions is located. Now at Carleton College, Minnesota, his research work is in the history of marine science, technology, and ocean exploration. He is well qualified to bring fresh eyes and insights to this somewhat different history of the evolution of oceanography.

Some scholars date the origin of modern oceanography to the 1874–76 British Challenger Expedition. Adler disagrees and makes a good argument that the timeline should begin at the start of the 19th century. He asserts that much of the form and function of modern oceanography had its origins in British and European concerns about overfishing in the North Atlantic and its bordering seas. Fishing was made much easier by more efficient catch methods using steam-powered fishing vessels that replaced sail-powered boats. Fisheries regulation, exploitation, and conservation depended on knowledge of the stocks and their variabilities.

In addition to marine biology, technological progress in the 19th century benefited from increasing governmental interests in developing knowledge of the seas. Also, there was evolving public interest in the popularized “mysterious realms” of the oceans. Increased abilities to capture live and dead creatures fueled public imagination and spurred development of private and public aquaria. All this was aided by an increasing volume of ocean-themed literature.

Adler begins with the evolution and expansion of marine-related sciences during the first half of the 1800s. Early scientific work eventually progressed from experimentations by individual researchers to larger cooperative efforts.

By the second half of the 19th century, national voyages of exploration, conquest and commercial development stimulated the quest scientific knowledge about the sea. In particular, the advent of coastal marine biological stations in Europe, England, and the United States was where modern oceanography had its nascence. In time, the stations also were where international cooperation in marine sciences began.

Much of the scientific progress at sea and on shore was made thanks to the participation of enlightened government leaders and wealthy sponsors. A good example of the latter is Prince Albert I of Monaco. In the last years of the 19th century and into the early 20th he devoted much of his life to oceanography, using his wealth, royal yachts, and active participation to greatly increase contemporary knowledge of the sea. His high visibility also helped bring to public attention the importance of the World Ocean.

The author suggests that the beginning of international marine sciences cooperation began in the mid-1800s. It was not until the early part of the 20th century that it began to be widely adopted and when its inherent economies and efficiencies were recognized. Also, increasing private philanthropy continued to play a major role in the creation of larger entities. For example, in 1903, the Scripps Oceanographic Institution was largely made possible by support newspaper publisher E. W. Scripps and his sister Ellen. And it was Rockefeller Foundation money that was instrumental in the creation of the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in 1930.

Adler suggests that during World War II there was limited international cooperation. This may be technically correct, but the greatest progress in the United States and other major maritime powers took place during that time. Superior knowledge of the marine environment was vital for prosecution of war at sea and was especially urgent for antisubmarine warfare. Record funding was invested in wartime oceanographic research. Government support has remained the single largest investor in ocean-related research.

The fifth and final chapter offers Adler’s perspectives on the current state of oceanography’s evolution. Some of the issues he discusses are the impact of the Cold War, international cooperative developments, governments as major sponsors, and how increasing military investments have both changed and enriched this interdisciplinary field.

New technologies and operational techniques are rapidly making science at sea vastly more productive. While the marine stations remain important, almost all progress is being made through the use of platforms in space and high-tech devices at the surface as well as under the sea. Remote sensing oceanography provides large-scale data that cannot be done any other way while manned and unmanned submersibles have taken humans inside the oceans to permit in situ observations. Even the relatively cheap and simple use of scuba diving can take scientists into the shallow upper reaches of the World Ocean.

This book may be related to Adler’s doctoral dissertation, but it is not a dry academic treatise. The writing style is lucid and easy to follow. Its dissertation origins are further suggested by its 69 pages of notes, acknowledgments, and the index. Notes alone fill 57 pages, all of it good reading by itself.

Scholars and lay readers will find Neptune’s Laboratory a good addition to the body of literature about the sea.

Dr. Walsh, a marine consultant, is a retired naval officer and oceanographer. During his naval career, he served at sea in submarines and ashore in ocean-related research-and-development assignments, including copiloting the bathyscaph Trieste to 35,813 feet down into the Challenger Deep in 1960.

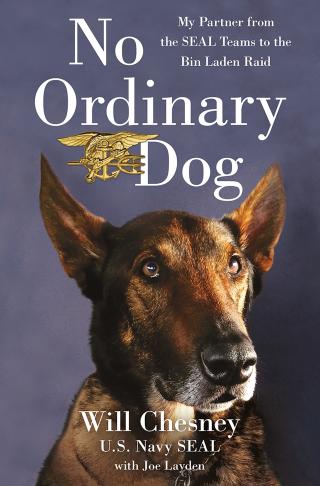

No Ordinary Dog

Will Chesney, with Joe Layden. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2019. 352 pp. $28.99.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Commander Travis Howard, U.S. Navy

This is no ordinary war memoir. At its core, this is a story about a bond between man and dog and a heartfelt tribute to some special unsung heroes: K-9 warriors that serve alongside our nation’s fighting forces as highly trained military working dogs. This is the case of Will Chesney, who became a SEAL dog handler at the height of the war on terrorism and took his combat assault dog, Cairo, through some of the toughest ordeals both on and off the battlefield.

Chesney’s story starts as many veterans’ do: recalling his earlier life, SEAL training, and overseas deployments as a special operator. After showing interest in the rapidly growing partnership between special forces and military working dogs, Chesney is partnered with a special Belgian Malinois named Cairo, and they form a bond that quickly surpasses “man’s best friend.” After excelling in several operations, including one in which Cairo was critically injured but made a near-full recovery, Chesney and Cairo faced the ultimate antiterrorism mission: Operation Neptune Spear, which resulted in the elimination of Osama bin Laden.

Ultimately, though, this book is about the aftermath of that operation and the hundreds that came before it. Chesney’s battle with debilitating medical problems and brain trauma as a result of his work brought an end to his SEAL career, but in a success story that would restore the faith of any cynical sailor, the Navy ultimately did the right thing in allowing Cairo to retire with his handler, where they could take care of each other.

The author’s descriptions of his battles with traumatic brain injury, military bureaucracy, and diagnosing post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) are truthful and sometimes raw, and will leave readers with a sense that the military still has a long way to go in understanding how to treat these life-changing injuries that often do not have visible manifestations.

The author’s conversational prose, use of dialogue to set the scene, and witty insight into the life of special operators makes this book hard to put down until you have consumed every page; if you are a dog lover, be prepared to get a bit emotional at times. This is a great read for anyone, not just military professionals, as it presents a truly different story in the lexicon of post-9/11 war memoirs: through the eyes of a SEAL dog handler and his loving tribute to his canine partner.

Lieutenant Commander Howard is a career naval officer and U.S. Naval Institute Life Member. He is a frequent contributor to Proceedings and several other professional venues.

New & Noteworthy

By Lieutenant Commander Nicholas Hoffmann, U.S. Navy

Deglobalization and International Security

T. X. Hammes. Amherst, NY: Cambria Press, 2019. 263 pp. Notes. Biblio. Index. $39.95.

In this latest part of the Cambria Press Rapid Communications in Conflict and Security series, T. X. Hammes gives a brief overview of the 21st century’s wide-ranging economic changes and explains possible impacts in the realm of international security. Seeing the rise of new technologies such as 3D printing and artificial intelligence as constituting a fourth industrial revolution, he notes that these technological leaps may make it easier to manufacture locally versus globally. Militaries also will benefit from this new industrial revolution, with the increasing prevalence of unmanned systems, nanotechnologies, and hypersonic projectiles.

Deglobalization and International Security provides an often sobering look at the changes the world is experiencing and the challenges it presents to both military and civil leaders. Tying in rapid economic change to larger picture strategic considerations, this work is a good read for academics as well as those in leadership roles in the armed services or industry.

Blind Bombing: How Microwave Radar Brought the Allies to D-Day and Victory in World War II

Norman Fine. Lincoln, NE: Potomac Books, 2019. 225 pp. Notes. Biblio. Index. $29.95.

Blind Bombing tells the story of the development and implementation of a now-basic military technology—the resonant cavity magnetron. This “heart” of a radar set allowed the Allies to develop radars at the next level, one so far above Axis radar technology that author Norman Fine likens it to the difference between a musket and a rifle. Armed with these new microwave radar sets, Allied aircraft were better able to conduct antisubmarine campaigns at sea and strategic bombing campaigns over land, regardless of weather.

The book begins by describing the state of radar technology at the beginning of the war, and the Anglo-American effort that led to the magnetron and the use of more precise radar to counter the German U-Boat threat. The last third of the book discusses “blind bombing” proper—the use of radar-equipped Pathfinder B-17s to initially find the target and drop bombs, allowing non-radar-equipped planes to guide off of the initial bursts. Blind Bombing sheds light on vital, tide-turning innovation.

The National Tour of the USS Constitution, 1931—34

Lieutenant Commander Phillip K. Parker, U.S. Navy Reserve (Retired). Self-Published, 2019. 104 pp. Sources. Notes. $15.

As nation’s oldest warship, the USS Constitution’s only scheduled under way each year is an annual “turnaround” cruise in Boston Harbor. However, for three years in the early 1930s, the Constitution, then recently restored, embarked on a goodwill tour to both coasts. She made 90 stops and hosted tours for more than 4.5 million visitors.

Phillip Parker, whose great-uncle was stationed in the Constitution for the cruise, meticulously documents the ship’s three-year voyage. Using original documents, logs, and records, he reconstructs the ship’s path, which included a transit of the Panama Canal. He also profiles the captain and others on the crew and explains that the goodwill tour was intended to raise the profile of the Navy during the Depression and a period of constrained naval budgets. Parker’s short work spotlights this remarkable voyage and is recommended to anyone with interest in the Constitution or the Navy’s interwar years.

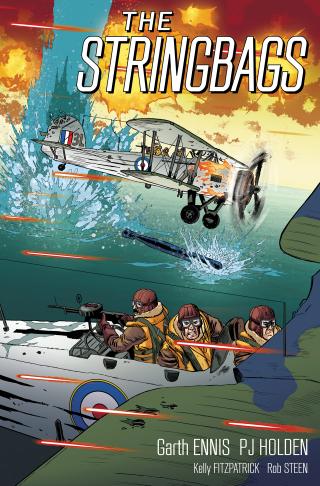

Garth Ennis. Illustrated and colored by P. J. Holden, Kelly Fitzpatrick, and Rob Steen. Annapolis, MD: Dead Reckoning, 2020. 186 pp. $29.95.

Set in the first half of World War II, The Stringbags is the latest historical graphic novel from Dead Reckoning, an imprint of the Naval Institute Press. Functionally obsolete when introduced, the slow-open-cockpit biplane bomber of the title was a mainstay of naval aviation for the British in the first portion of the war. Likened to a string shopping back for its versatility, the aircraft were essential to the British victory at Taranto and the sinking of the Bismarck. Their crews also boldly, but less successfully, attempted to interdict the German fleet in the “Channel Dash.”

Veteran comics writer Garth Ennis brings this period of the war to life through his three-man Swordfish crew and their colleagues—based on real-life Swordfish aviators. Through interesting turns of events, his crew is able to participate in all three crucial Swordfish battles, allowing the reader to see the impact these planes had on the war effort. Action packed and at times poignant, this graphic novel will be enjoyed by World War II buffs and graphic novel fans alike.

Lieutenant Commander Hoffmann is a career surface warfare officer. He has served in several ships and afloat staffs and currently serves as the damage control assistant in the USS Theodore Roosevelt (CVN-71).