The recently announced goal to improve Navy education and training for the exercise of sea power is very important.1 Military schools and universities that teach sea power as issues of policy and strategy must be careful not to overlook the tactics and combat aspects of the subject. Too little is being written about winning battles. There are three elements of an effective strategy. First, its aims: What are our naval forces’ goals and why? Second, its ways: What are the operational and campaign plans that can achieve the goals? Third, the means: What forces are available and what tactics can they employ to execute the campaigns successfully?

The Aims: Maritime Superiority

If the aim of sea power is to constrain any prospective enemy from going to war, or to defeat the enemy at the lowest possible level of violence if war ensues, then in many cases this aim defines a maritime strategy of naval supremacy. But supremacy now is too ambitious to execute against every prospective enemy. A lesser goal of maritime superiority sufficient to achieve sea control is still achievable, but superiority is becoming more challenging because it means defeating an enemy who has the power to choose the time and place of attack. The U.S. fleet must be ever-alert to fend off every attack, including one that may come with little or no warning.

The Ways: Tactical Skills

The main difference between the education and training domains is pace. A tactician must gather information needed for an attack and—not without risk—strike before the enemy can strike. Sound tactics entail tactical competency, which requires constant tactical drilling. Tactics mainly are in the realm of physical activity, in contrast to strategic thinking, which occupies the realm of mental activity. Modern tactics entail swift action and must be timely. The pace of strategy is leisurely by comparison. A navy that suffers collisions with large, slow merchant ships is unprepared to avoid “collisions” with supersonic antiship cruise missiles.

Tactical competency in future battles must include fighting with and against unmanned and robotic air, surface, and subsurface vehicles, some of which will operate in swarms. It requires proficiency at information warfare, including offensive and defensive cyber operations. The growing ability to gather and deliver vast quantities of information by many means of search, detection, and tracking demands new tools in the fast-growing field of artificial intelligence to sort and swiftly deliver the right information to tactical decision makers who must attack effectively before the enemy strikes.

Logistics are part and parcel of tactics because small and numerous forces must be based forward in friendly nations to show U.S. support of its allies. Marine Corps forces in advance bases can threaten attacks in enemy littorals and should be an important component of 21st-century sea power, as green waters become more dangerous and short-range surprise attacks with missiles, torpedoes, and mines are a growing concern. Observe the role reversal; instead of the Navy supporting amphibious assaults, as was the case in the 20th century, Marines in advance bases prepositioned in friendly states will support the Navy’s capacity to threaten an enemy’s control of its home waters.

The Means: A Multifaceted Tactical Education

Tactical competency will require a comprehensive plan to prepare our leaders to wage war and win battles. The most important task the newly appointed Department of the Navy Chief Learning Officer will have is to designate the roles of the education and training establishment. The Naval Postgraduate School (NPS), Naval War College, Naval Academy, and Marine Corps University will each have different emphases that require clarification. The Chief Learning Officer must play a complementary role, especially in shipboard training and individual officer and enlisted competency to fight as well as operate and repair shipboard equipment.

Here are five steps to a multifaceted tactical education:

- The Navy must recruit and train the right officers and enlisted personnel. What do we mean by “right”? At a minimum, this means training and promoting more “digital sailors” to man the fleet.

- The Navy must prepare its leaders to fight with the right collective blend of undergraduate and graduate education. The current subspecialty code (P-Code) system that governs selection of officers for graduate education is inadequate. Most important, for line officers, every sea tour is a payback tour, not just when serving in P-Coded billets. This is especially true for those who study science, technology, engineering, and mathematics (STEM). To correct the broken P-Code system, the Chief of Naval Operations should convene a panel of retired Navy leaders such as Admirals Mike Mullen, Patricia Tracey, Henry Mauz, and Bill McRaven to recommend a better mix of graduate education for seagoing line officers. That in turn will govern the graduate education quotas at NPS and civilian universities.

- More line officers must attend graduate school for at least 18 months to achieve individual core competencies. Nonmilitary analogues are law school and medical college. NPS is devoted to the needs of the Navy and the armed forces. The Naval War College is its companion for more senior officers.

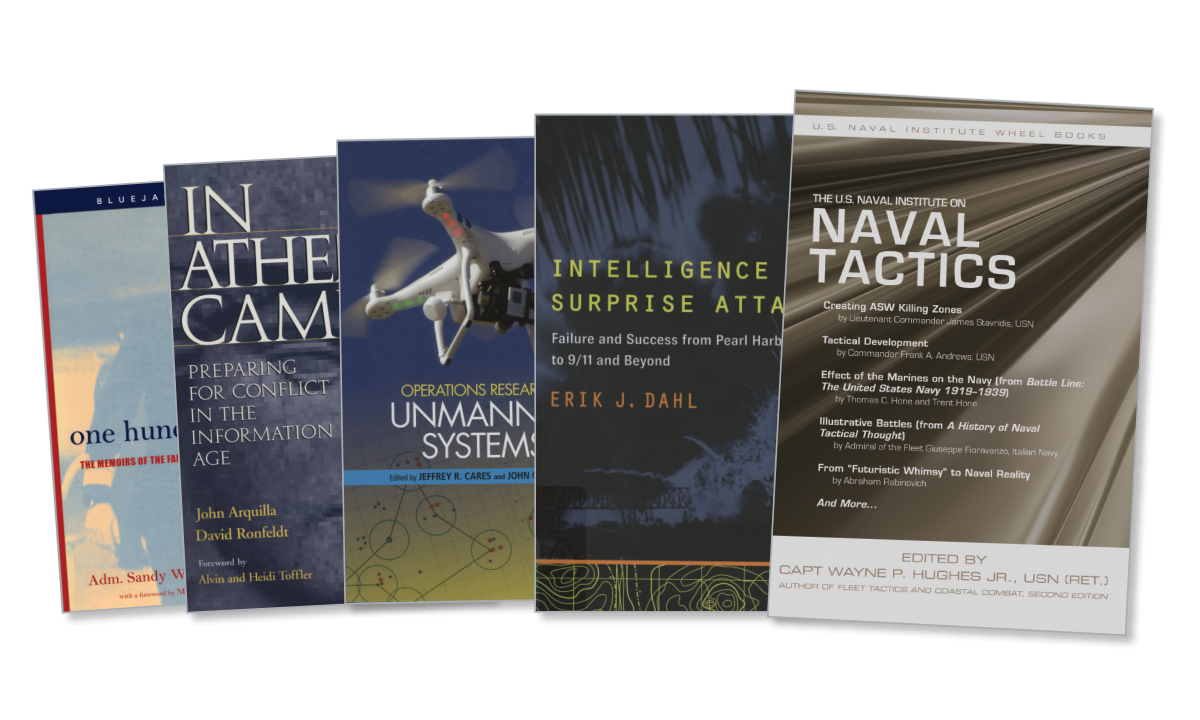

- The service must continue officer education with short courses for combat readiness. Nonmilitary analogues are short courses for doctors, nurses, dentists, and financial advisors to keep them current on the latest practices in their professions. In addition to short courses, the Navy and Marine Corps must inculcate an attitude of continuous professional reading and make sure officers and senior enlisted have time to read the best journals, such as the Marine Corps Gazette, the Naval War College Review, and the U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings. Leaders also should be reading books on combat and tactics, such as Sandy Woodward’s One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander, and encouraged to write articles, not to register complaints but to design new tactics that will win battles.2 Finding time will not be easy in today’s overworked fleet, so a successful sea power strategy should include peacetime operational plans that do not overwork seagoing officers.

- Instead of advancing “perfect” officers, future Navy promotion boards must promote officers who will take risks to win battles at sea. They should seek out daring officers such as Ernest J. King, Chester Nimitz, Bradley Fiske, Arleigh Burke, Holland M. Smith, Mike Mullen, Patricia Tracey, Henry Mauz, and even William Halsey, whose bold leadership was indispensable in the Solomon Islands campaign before he later faltered. Encourage promotion boards to remember heroes such as John Paul Jones, who said, “I have not yet begun to fight,” and David Glasgow Farragut, who said, “Damn the torpedoes; full speed ahead,” at critical junctures. The Marine Corps has its own examples of courageous leaders, including Generals Clifton Cates, David Shoup, and Alfred Gray.

AN Example: NPS SEA Curriculum

Sea power is not achieved by a policy or strategy. Words do not achieve combat readiness, not even the words in well-expressed combat doctrine. Tactical readiness means training present and future leaders to fight in the domains of action and risk.

For several decades, NPS has been aware that the fleet has been losing its understanding of what is required to fight and win future battles at sea. It has tried and failed to make this clear to Pentagon, Navy, and fleet leaders. More than 15 years ago a small coterie of career seagoing line officers at NPS designed a single curriculum with inputs from numbered fleet commanders’ staffs. Responding to the direction of the Vice Chief of Naval Operations, their purpose was to prepare young line officers to develop and execute naval tactics, and who, when called on, could win battles against any enemy. The focus was on a well-rounded education in systems engineering analysis (SEA).

The original curriculum was 18 months long and dense with computer and information warfare technology, tactical and campaign analysis, engineering physics and weaponeering, and strategic principles undergirding policy. The SEA curriculum also has a course in naval tactics. The Navy successfully marketed the curriculum for several years, initially almost filling the quota of 20 students. NPS made clear there was no need to P-Code billets because graduates would apply what they learned in every sea and staff tour. Unfortunately, the number of students sent by Navy Personnel Command has dwindled, year after year.

A simple first step to restore tactical competency for sea power would be to fill every SEA curriculum billet with carefully selected junior officers who demonstrate promise as future commanding officers. The Vice Chief of Naval Operations should approve the curriculum and select the students.

Naval battles are won by tactical commanders who know when to act, move swiftly, and take calculated risks to attack first and effectively. The Navy must integrate tactical education into its graduate school programs if it wants to produce leaders who are prepared to fight and win future battles.

1. Under Secretary of the Navy Thomas B. Modley, Education for Sea Power (E4S) Study, 19 April 2018.

2. ADM Sandy Woodward, RN, One Hundred Days: The Memoirs of the Falklands Battle Group Commander (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1992). Assisted by Patrick Robinson, Admiral Woodward lets you feel the surprises, operational challenges, tactical successes, and frightening technological disappointments of the man in the hot seat. Other essential books on a short list should include Erik Dahl, Intelligence and Surprise Attack: Failure and Success from Pearl Harbor to 9/11 and Beyond (Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2013); John Arquilla and David Ronfeldt, eds., In Athena’s Camp: Preparing for Conflict in the Information Age (Washington, DC: RAND, 1997); Jeffrey Cares and John Dickman, eds., Operational Research for Unmanned Vehicles (Hoboken, NJ: John Wiley, 2016); ADM William McRaven, USN, Spec Ops: Case Studies in Special Operation Warfare, Theory and Practice (New York: Presidio Press, 1996); and Wayne Hughes, ed., The U.S. Naval Institute on Naval Tactics (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2015).