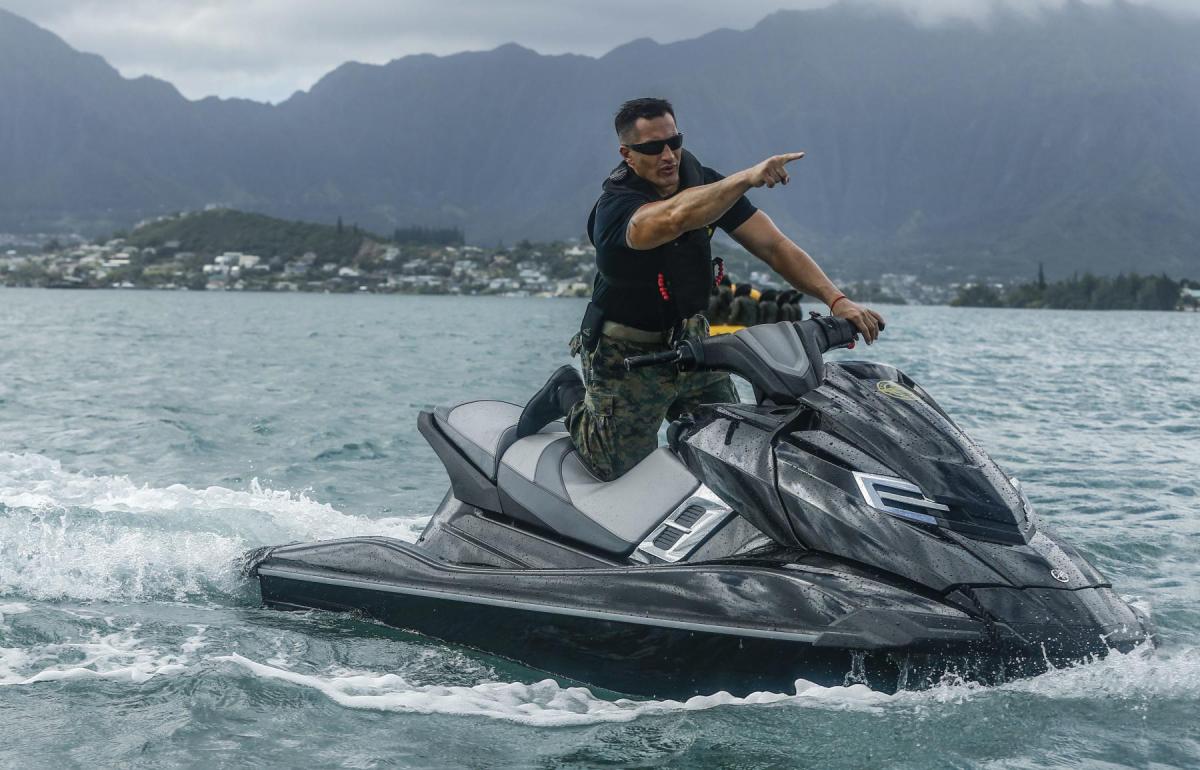

In the 38th Commandant’s Planning Guidance, General David Berger says the Marine Corps “must continue to seek the affordable and plentiful at the expense of the exquisite and few when conceiving of the future amphibious portion of the fleet.” Distributed operations and expeditionary advanced base operations (EABO) both will require dispersed, low signature, low cost amphibious platforms. Personal watercraft, commonly referred to by the brand name Jet Ski, might be an answer.

Benefits

While not entirely amphibious—they cannot operate on land—personal watercraft can move through just about any water environment, whether coastal, riverine, or open water. They are faster and more maneuverable on water than the amphibious assault vehicle (AAV), with many able to reach speeds up to 60 miles per hour. Many also have ranges of up to 100 miles and require relatively little fuel.

Because of their low logistical and maintenance requirements and small size, they would allow Marine companies to disaggregate into smaller units while maintaining maneuverability and sustainability. They are small and light enough to fit in any ship and almost any transport aircraft in the fleet and can be moved into and out of operational areas with ease. While larger vessels present lucrative targets for enemy defense systems, a small unit equipped with personal watercraft would be able to remain widely dispersed, limiting the enemy’s ability to engage them with precision weapons and limiting the value of any single target.

In addition, personal watercraft are relatively inexpensive. Most range from thousands to tens of thousands of dollars, compared with hundreds of thousands or millions of dollars for amphibious systems such as the AAV or Mark VI patrol boat.

Limitations

While highly versatile, personal watercraft do have a number of limitations. They have no armor, and when engaged with the enemy, would have to rely on speed and maneuverability for protection. This likely would make them better suited to reconnaissance, security missions, and patrolling in low threat environments.

They also would be difficult to coordinate when operating as a widely dispersed unit and would require at least a moderate amount of training to use. Personal watercraft also are fairly loud. A military version would have to be modified to allow operators to get closer to shore without being detected.

Perhaps the biggest issue is that these craft cannot operate on land. This begs the question of what Marines would do with them once they go ashore. But these craft likely would be used primarily for reconnaissance; Marine operators would observe and report on enemy activity rather than directly engage. If Marines became engaged with an enemy on the shore, they would have to break contact—a task conducive to the crafts’ high speed—and call for heavier units to conduct offensive operations.

First Steps

Personal watercraft would require new employment concepts. The Marine Corps already possesses the Combat Rubber Reconnaissance Craft (CRRC), an 8–10 passenger craft primarily used by the reconnaissance and special operations communities. Whether personal watercraft will be operationally feasible and provide a capability not offered by the CRRC will have to be determined.

But as General Berger has noted, “Success [in EABO] will be defined in terms of finding the smallest, lowest signature options that yield the maximum operational utility”—and personal watercraft certainly are among the smallest, lowest signature platforms available. Teaming them with small unmanned underwater and aerial vehicles could further reduce risk and extend their reach. The Navy and Marine Corps could benefit by experimenting and war gaming their use in ship-to-shore operations, coastal and riverine patrolling, reconnaissance, beach surveys, and other tasks relevant to EABO and distributed operations.