When high school senior Horacio Rivero Jr. took the Navy medical exam in San Juan, Puerto Rico, for admission to the U.S. Naval Academy in 1927, he received a waiver for his weight of 112 pounds.

I almost didn’t make it because at just under five feet, two inches, I was too short. Fortunately, the head of the Board, a captain, was also short. He put his thumb at the bottom of the tape, stretched it, and got that quarter inch to put me over the top.

During plebe year at the Academy, an officer had trouble looking down and reading the name stenciled on Rivero’s blouse. “What’s your name?” the officer asked. “Rivets?” Thus, Horacio “Rivets” Rivero was born. He would carry the nickname proudly from midshipman, to four-star Vice Chief of Naval Operations, and beyond.

Following commissioning in 1931, Rivero honed his skills in ordnance engineering and would serve on board battleships and cruisers into the Battle of the Pacific. In this edited excerpt from his Naval Institute oral history, Rivero recalls two experiences in combat as executive officer of the cruiser USS Pittsburgh (CA-72) in 1944–45.

In March 1945, the carrier USS Franklin (CV-13) was bombed. We were in the task force, and we were told to take her in tow. It was a difficult thing. We put our cable over because the Franklin’s had been damaged. We towed the carrier for 24 hours.

Our skipper stayed on the bridge. I was on the fantail with my foot on the cable, and the chief engineer was in the engine room. We had a three-way telephone conversation. I would say “Take off two turns,” because I felt the tension in the wire. It was a small wire to tow that big ship. We started very slowly, probably three or four knots. The Franklin would sail up into the wind, almost turn us around. Mind you we were in the range of Japanese aircraft. In the meantime, they were able to get the Franklin’s engineering plant back into commission and we finally let her go.

The other big issue I faced as executive officer was damage control, and the precautions we were taking as we headed into a typhoon on 4 June 1945. Our first lieutenant and damage control officer was Commander Joe Kircher, and he had his crew well organized. We could see the typhoon on the radar and couldn’t understand why the whole task force was going full speed into that damn storm.

We were making, I forget how many knots, but we weren’t making any headway. Early in the morning, before dawn, I got worried about big pieces of equipment breaking loose, because the ship was working so heavily in the seas and rolling so. I suggested to the captain, and he agreed, that we set “material condition Zebra,” which is what you set when you go to general quarters. You tighten everything up, close all the watertight doors, and everybody gets out of certain areas.

When you set Zebra, the forward part of the ship is not occupied. Everybody leaves, and it is closed up, which was fortunate. When that part of the ship broke off, we had no casualties.

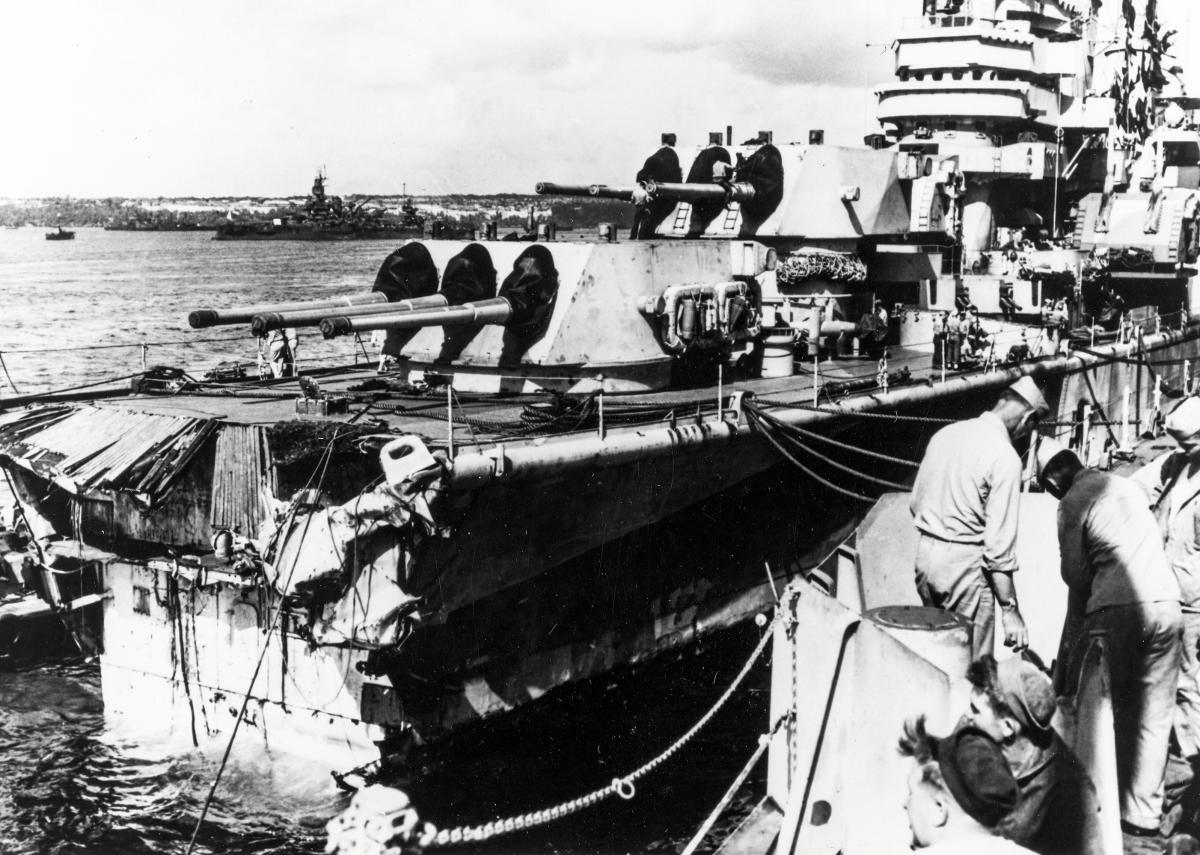

When the bow broke off, I saw it. I was up on the bridge with the captain. The bow was moving up and down, and it finally just wrenched off—more than 100 feet of the ship gone. A subsequent investigation determined it was a structural weakness in the keel.

We had the problem of keeping the ship from sinking. The typhoon was still going. The anemometer just flew off after 125 knots. The captain decided to turn the Pittsburgh around, rather than have the seas batter against that regular, light compartment bulkhead. Turning around without capsizing was a feat in itself. Then the typhoon spent itself, and we were able to steam 900 miles to Guam at a very slow speed.

Watch newsreel footage of the typhoon and the damage to the Pittsburgh below: