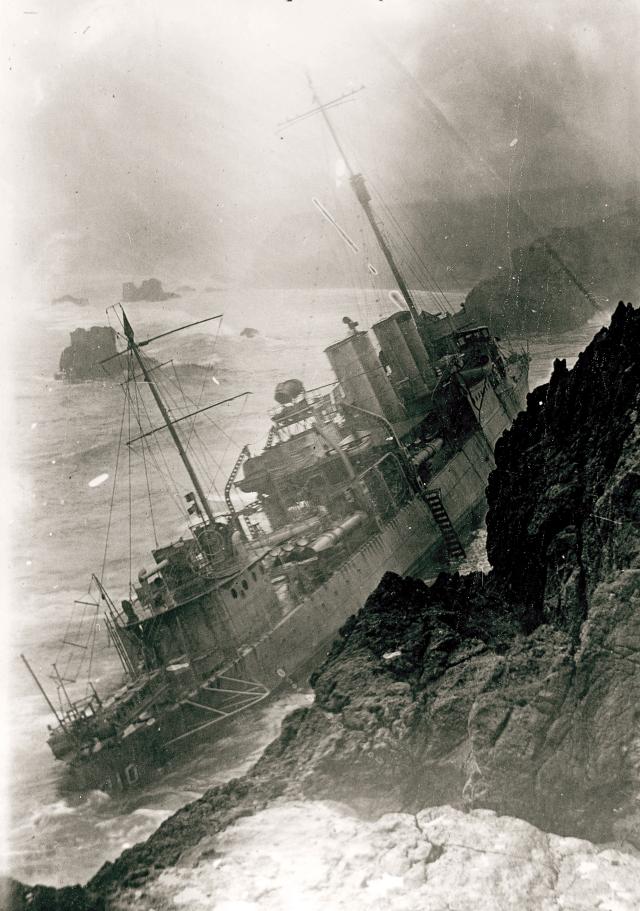

Twenty-three sailors died in the waters off the California coast on 8 September 1923. When Commodore Edward H. Watson errantly led his formation of 14 destroyers to disaster on the rocks of Honda Point, he initiated the largest-ever peacetime loss of U.S. Navy ships. Despite heavy fog, inconsistent navigational data, and a failure to take precautionary soundings, six captains followed his order to steam in close formation at high speed to exercise a wartime scenario. All of those ships were lost. Two captains disobeyed the order and managed to save their ships.1 In the end, the general courts-martial held each captain accountable for his decision to follow orders instead of trusting his own judgment.2

Commanding officers own the decision, and the risk, in naval operations, but absolute authority does not equate to perfect information or even perfect judgment. A commander unintentionally could be charting a course toward disaster, which could have lethal consequences. A bad idea in the technical operation of a ship may only damage equipment, but a strategic error could cost hundreds of thousands of innocent lives. The Navy’s hierarchical structure often makes junior personnel reticent to challenge the decisions of their superiors; however, junior personnel may possess subject matter expertise the commander lacks, or they simply may see another way forward based on their experience. Voicing dissent can be the difference between success and failure, and even life and death.

The Navy sometimes refers to dissent by junior personnel as “speaking truth to power.” This can be helpful because it dispels negative associations with words such as disloyalty, disobedience, defiance, and insubordination. Still, the idea of speaking truth tends to oversimplify dissent. Junior service members must recognize that they may have incomplete information or lack broader context. Their “truth” may be just one of many, and there always will be career peril in voicing dissenting opinions to senior leaders. However, that does not absolve them of the responsibility to speak up when they think things are going south.

This is the heart of the “questioning attitude” principle of operational excellence introduced by Admiral Hyman Rickover, the father of naval nuclear power, who understood that the normal hierarchical military culture would not work for operating a nuclear reactor at sea.3 Aviators refer to not voicing one’s concerns in the cockpit as “sandbagging” and explicitly forbid it. Much like the Convention on the International Regulation for Preventing Collisions At Sea Rule No. 2, if you can prevent a collision, you have the obligation to do so.

It may be perilous, and it may violate normal procedures, but junior personnel have a moral imperative to voice dissent in naval operations. The relentless study of the art and science of naval operations should inform your technique and the degree to which you express dissent. It will never be easy to determine when to trust your own judgment and when to put your faith in your commander’s decision to the contrary, but you accepted that challenge when you took your oath. By putting on the uniform, you embraced the moral imperative to voice your dissent.

Maneuvering in the Ethical Midfield

When then-Secretary of Defense James N. Mattis wrote of the “ethical midfield” in 2017, he was giving guidance to the Department of Defense on handling matters of ethics, which permeate all decisions in the military:

I expect every member of the Department to play the ethical midfield. I need you to be aggressive and show initiative without running the ethical sidelines, where even one misstep will have you out of bounds. I want your focus to be on the essence of ethical conduct: doing what is right at all times, regardless of the circumstances or whether anyone is watching.4

We also must abide by other rules when operating on the proverbial field. For example, certain legal constraints, such as the Uniform Code of Military Justice and Standing Rules of Engagement, bound behavior. We also need to recognize the limitations of our own expertise. The ethical midfield, together with the boundaries of legal authority and expert credibility, carve out a maneuver space that people in uniform must navigate aggressively and faithfully. Passivity is not an option. Even when decisions do not involve an ethical dilemma, the moral imperative to voice dissent in the Navy still exists. Ours is a business of violence and death. To remain silent in the face of decisions you believe to be wrong equates to an immoral act, and you accept responsibility for the potential lethal consequences, however distant or remote they may be.

In combat, leaders often do not have time to consider the merits of orders from superiors. One way to achieve morality in combat is to faithfully and promptly execute a superior’s orders with supreme discipline. In 2018, Secretary Mattis wrote of the critical importance of discipline: “All service members learn to fight well by doing the little things perfectly, otherwise they cannot possibly get the big things right when all goes wrong.”5 For example, when a commander at higher headquarters orders a ship to strike a target ashore, he or she owns the moral decision to kill. The ship’s role is to execute with precision so the ordnance hits the intended target. But if the commanding officer (CO) misses the target or strikes too late and kills innocents, he must accept responsibility. Of course, if the CO has reason to believe the strike is inadvisable, he or she has a choice to either voice dissent or accept moral complicity in executing orders. All commanders should strive to master the ability to make this decision in a timely manner.

The Navy gives junior personnel responsibility over a relatively narrow scope of operations, but within their scope of responsibility their superiors expect them to achieve subject matter expertise. Senior leaders rely on them to understand their craft to a level of detail that few outside their rating or community will ever achieve. As sailors gain seniority, their scope of responsibility expands, and they rely more on their subordinates for detailed knowledge.

This layering of tactical and technical expertise, combined with active communication up and down the chain of command, is the framework that makes the Navy effective. When the framework of training and communication breaks down, as it did in the USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) and Fitzgerald (DDG-62) collisions, in which sailors did not know how to operate their radar and ship control consoles, the results can be catastrophic.6 The John S. McCain’s chief boatswain’s mate, Jeffery Butler, acknowledged he failed to adequately train his sailors on the newly installed Integrated Bridge Navigation System. “What I should have done, I should have gotten knee-deep in that tech manual . . . dissect it page by page,” Butler said at court-martial.7 “I could have told my junior sailors how to better operate their systems.”8 If you do not know how to operate or maintain your equipment, or you do not understand the tactics for which you are assigned, you cannot offer dissent to prevent a tragedy. By your ignorance, you are complicit in the consequences. Similarly, if you have attained expertise, but elect not to voice dissent, you’ve made a moral decision and should be held accountable. In technical and tactical matters, discipline and readiness to dissent are the foundations of morality.

At the most senior levels, officers make operational and strategic decisions, but the decisions largely are of the same nature. The key differences usually are the scale of impact and the time and resources available to decide. Military decisions made by four-star admirals and political leaders could involve months of staffing and could affect human life on a global scale. Cross-functional staffs support flag officers to help them make strategic and operational decisions, which is where junior officers can exert influence.

As a staff officer, your commander expects you to learn your portfolio quickly and be the subject matter expert he or she can lean on for sound advice. Staff work may seem mundane or insignificant compared to operational billets in a ship or squadron, but the decisions you influence can have much greater impact. Here again, the decision to dissent involves high stakes and a moral imperative. Since your commander assumes you are the owner of uniquely detailed information, he or she expects you to dissent when the staff is going in a direction you find inadvisable. If you do not voice dissent at some point during the decision-making process, you’ve robbed the commander of the opportunity to consider your alternative perspective, and you must live with the moral consequences of your inaction.

Some decisions by naval commanders are not directly tactical, operational, or strategic but still address other complex and critical issues, such as people, money, and infrastructure. Like strategic decisions, decisions on supporting factors usually do not need to be made in real time. Commanders often treat these decisions as strategic because their ramifications can be just as far-reaching and long-lasting. Accordingly, most staffs include a directorate devoted to personnel (i.e., “N1”), logistics (“N4”), communications (“N6”), and resources (“N8”). These staffs must equally be prepared to offer their best professional advice and dissent in the face of commander’s decisions with which they disagree.

The Dos and Don’ts of Naval Dissent

The obvious question is: How does one dissent and still remain a credible voice in the decision-making process? In other words, disagreeing with your commanding officer doesn’t do much good if you get kicked out of the meeting or fired the next day. There is a right way and a wrong way to fulfill your moral obligation to dissent. Here are a few tips to help you stay on the field and continue to guide your organization from below:

• DO find the appropriate venue.

One-on-one conversations are best, particularly if your commander gives you the latitude to speak freely. More commonly, you might find yourself in a small group of more senior officers in the commander’s office discussing the issue. If you wonder whether you have permission to speak up, the fact that you are in the room is permission enough. Be very careful in public settings. There is almost always a better time and place to offer your dissent.

• DO offer your honest opinion if the commander asks.

When the commander solicits your advice, give it honestly and fully, even if breaks with other advice already offered by those senior to you.

• DON’T be afraid to go off script and trust your gut.

If you are briefing the commander, he or she has implicitly asked for your advice. This is the one exception to dissenting in public. As the briefer, the commander has entrusted you with a unique role and believes you will offer your best advice, regardless of how controversial it might be.

• DON’T carry on blindly.

If you’ve voiced your dissent, the commander has heard you, and he or she persists on the present course anyway, likely it is time for you to stand down. In most cases, you can rest easy knowing that you offered your best advice based on the scope of your knowledge. In rare cases, it may be appropriate to carry on even after the commander acknowledged your dissent. Proceed carefully. You are near shoal water.

• DO prepare to think on your feet.

You need to strive to be the subject matter expert your commander expects you to be. Often, you will have only one chance to offer your opinion to the commander, and you will need to think on your feet, even for strategic decisions, since you will be involved in just one of many facets of the decision-making process. When the commander turns to you for advice, you should be prepared to give it, not tell him or her you will follow up later.

• DO earn the trust of your commander.

You will make more headway in convincing your commander that your way is the right way if he or she trusts your judgment. Earning trust starts from day one by demonstrating your confidence and competence as a sailor and shipmate. If the commander can trust you to do the right thing and do the thing right, then he or she will be more willing to listen to your dissenting opinion.

• DON’T let politics influence your dissent.

You are voicing dissent in your unique role as a member of the U.S. military, not as an United States citizen. You will, of course, have political views and opinions that might even be related to the military decision at hand, but politics should never be the basis on which you dissent. Civilian control of the military is a virtuous tenet of our republic. There always will be political leaders giving you lawful and ethical orders that go against your political beliefs. You swore an oath to support and defend the Constitution. Unless the order is unconstitutional, politics are no reason to dissent.

• DO remember why you are in uniform in the first place.

Use your oath as your primary aid to navigation. The decision to dissent is never easy, even after you understand your imperative to do so. Keeping your oath, and your reasons for joining the Navy, in your sights can help. Ultimately, the decision is yours alone, and the American people expect you to make it faithfully.

There is, of course, no comprehensive set of rules to get every decision on dissent correct. You will, at times, be convinced that your commander is erring by not heeding your advice, and you will be wrong. There also will be times you feel such strong conviction that, even in the face of unanimous opposition, you will feel compelled to maintain course and speed. Still, the likelihood of failure should not be a factor in your decision to voice your dissent.

The willingness to dissent is woven into the fabric of American culture. Psychologists call it “low power distance.”9 In other words, subordinates are more likely to express disagreement in the United States than in many other cultures. Telling our superiors when we believe they are wrong is a part of our national character. Of course, the “power distance” is greater in the highly stratified military culture, but the moral imperative to dissent in the Navy, rooted in life and death consequences, far outweighs the challenges we are sure to face.

Naval Dissent in Action

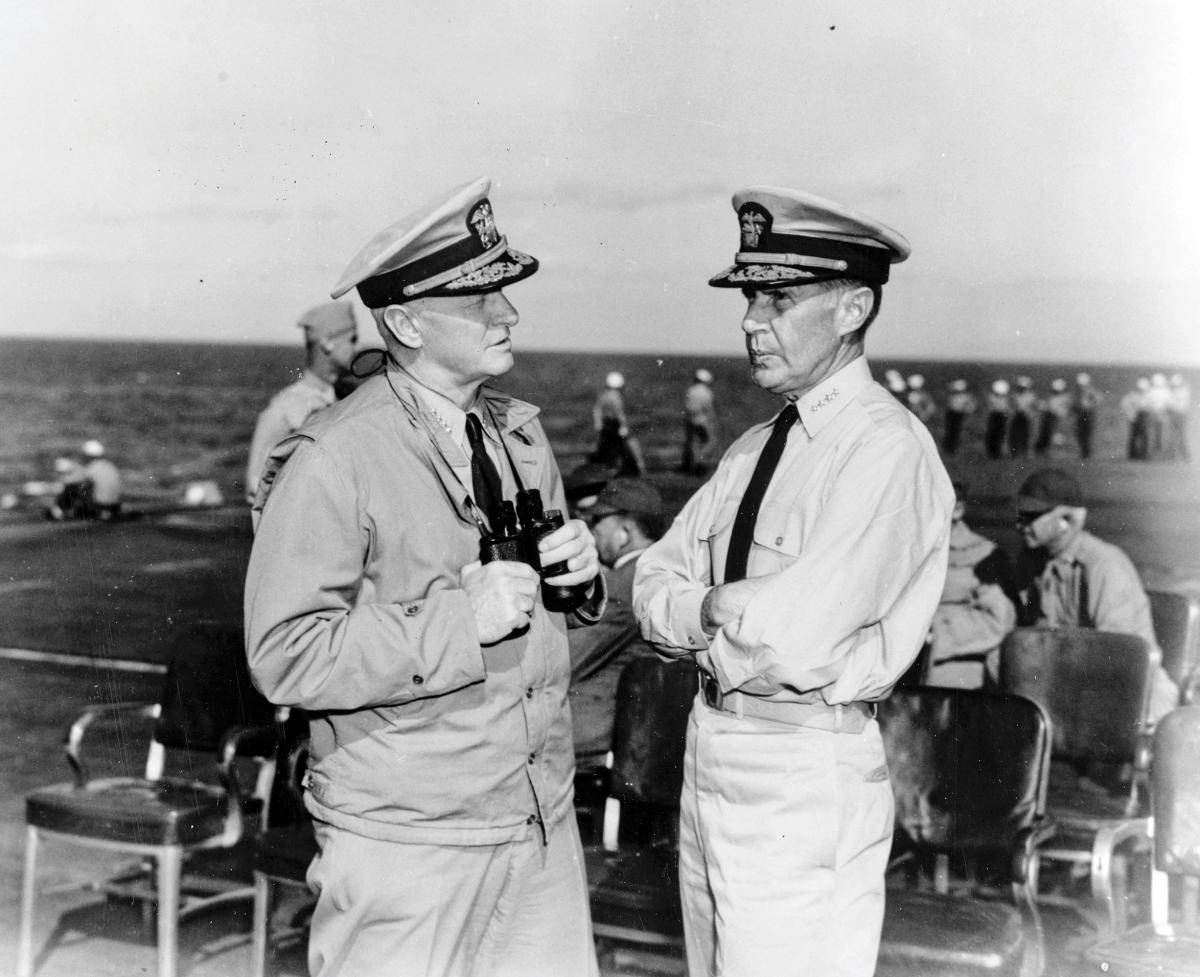

Sometimes tactical decisions have strategic impact. Consider two of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance’s key decisions at the Battle of Midway. Spruance intended to launch his aircraft within 100 miles of Midway. On hearing the Japanese attack on the atoll was under way, Admiral William Halsey’s chief of staff, Captain Miles Browning, who notoriously clashed with Spruance, advocated launching immediately in hopes of catching the Japanese while they were refueling aircraft on deck. Spruance went with Browning’s advice, which would prove to be astute.

Later in the battle, after three Japanese carriers had been sunk and the fourth was on fire, Spruance decided not to conduct a nighttime pursuit of the remaining formidable Japanese battle force and instead retreated eastward. This decision ran counter to Admiral Chester W. Nimitz’s implied intent to seek destruction of the enemy whenever one held the advantage. Against his staff’s recommendations, Spruance trusted his instincts that he had inflicted as much damage as possible and that his primary mission was to defend Midway. He would return in the morning to complete the mission and turn the tide of the war.

Both of Spruance’s decisions, one to trust his staff and one to trust his instincts, highlight the importance of dissent in naval operations. Had he stuck to his planned launch schedule, or pursued the enemy at night, his tactical decisions may have altered the course of world history.1

1. Alan Rems, “Out of the Jaws of Victory,” Naval History 30, no. 2 (April 2016).

1. Gayle Baker, Santa Barbara, Another HarborTown History (Santa Barbara, CA: HarborTown Histories, 2003), 76.

2. “Honda Point Disaster, 8 September 1923,” Naval History and Heritage Command (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 2002).

3. “The Pillars of the Program: Operational Discipline in the U.S. Navy Nuclear Propulsion Program,” Wilson Perumal and Company (2013).

4. GEN James N. Mattis, USMC (Ret.), “Ethical Standards for All Hands” (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2017).

5. GEN James Mattis, USMC (Ret.), “Discipline and Lethality” (Washington, DC: Department of Defense, 2018).

6. ADM John Richardson, USN, “Memorandum for Distribution” (Washington, DC: Department of the Navy, 2017).

7. J. D. Simkins, “Navy Chief Gets Busted Down in Rank at McCain Collision Court-Martial,” Navy Times, 24 May 2018.

8. T. Christian Miller and Robert Faturechi, “How the Navy’s Top Commander Botched the Highest-Profile Investigation in Years,” ProPublica, 11 April 2019.

9. Brent Hayward, “Culture, CRM and Aviation Safety,” The Australian Aviation Psychology Association (1997).