Crises in the U.S. Navy tend to be viewed as isolated problems. Sexual assaults, binge drinking,synthetic-drug rings, port-call prostitution, the “Fat Leonard” scandal, Tailhook ̓91, and the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62) and USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) collisions, however, all share a common thread—issues of character. The Navy’s core has been weakened by a culture that cultivates too many leaders who are distracted by goals such as promotion, command status, loss avoidance, or personal gratification, which causes them to make poor ethical decisions, compromising their character in the process. It is time to strengthen the character side of the Navy Leadership Development Framework (NLDF) and for Navy community leaders to drive programs that teach leaders to act with both competence and character.1 These new and effective sets of leadership development tools also will reinforce the development of and help retain the emerging millennial force.

Research into ethical leadership by Kenneth Goodpaster—a former Harvard Business School professor—can inform the understanding of the ethical problems facing the Navy today. Through case studies, ranging from the ethical collapse at Enron to the NASA Challenger and Columbia disasters, Goodpaster diagnoses “goal sickness” as the disease that drives ethical collapses by both organizations and individuals.2 Examining Navy crises through Goodpaster’s lens explains how personal and institutional goal sickness—the unbalanced pursuit of purpose in either individuals or organizations—has affected morality in naval leadership over the past several decades.3

Goodpaster uses Buzz McCoy’s “Parable of the Sadhu” to describe goal sickness. In 1999, Buzz, a senior leader in an investment firm, decides to take a six-month sabbatical to soul-search while climbing a Himalayan mountain. As he nears the summit, Buzz comes across an unconscious sadhu (holy man) dying from exposure. Buzz has to choose between helping the dying sadhu or finishing his ascent. Buzz chooses to leave the sadhu behind, later reflecting that he “missed an opportunity to obtain the perspective, balance, and spiritual growth that had prompted him to take the sabbatical in the first place.”4 In this sense, every Navy leader faces their own choices on the side of the mountain, and lessons from this parable provide a foundation to explore how goal sickness drives unethical decisions.

Goal-Fixated Leaders

Goodpaster’s research concludes that goal sickness is exhibited through the symptoms of “fixation,” leading to “rationalization” and “detachment.” Together, these three symptoms paint a picture of personal and organizational goal sickness that have corroded the naval service.

Fixation is defined as “the difference between determination, courage, perseverance, and tenacity [virtues] . . . and addiction, or dependency.”5 In his parable, Buzz was so fixated on his goal of the summit that, in his mind, reaching the peak became more important than the sadhu’s life.

In the naval service, the most obvious parallel to the “goal of the summit” is the career-long, organizationally demanding journey toward command at sea. The entire line-officer detailing structure is designed to keep leaders on a “golden path” to commander command and beyond. Navy leaders are taught that straying from this path or, worse yet, making untimely mistakes during critical milestone tours, will relegate them to the organizational off-ramp. The results of encouraging such single-minded careerism can have deadly consequences.

Consider the commanding officer of the USS William P. Lawrence (DDG-110), who was so preoccupied with recovering her ship to its strike group–prescribed steaming formation that the force of her corrective maneuvering during flight quarters threw a 20,000-pound, chained-down helicopter overboard with the two pilots still on board.6 With such a large number of officers fixated on doing the things necessary to achieve or succeed in command, the Navy increases the risk of outcomes that are inconsistent with proper risk management and personal character.

As a result of goal-fixation, leaders will often rationalize the poor ethical decisions that result. Later in Buzz’s parable, he describes meeting a Kiwi climber and rationalizing his abandonment of the sadhu, exclaiming, “Damned irresponsible of him for being here, half-dressed like this, at 18,000 feet!”7 In this, Buzz ignores the humane reality that underdressing for an extreme mountain expedition is hardly justification for a death sentence.

Rationalization of poor leadership practices is prevalent in the Navy, but it most obviously manifests in the marked increase in senior-level micromanagement identified in the 2014 Navy Retention Study.8 Fueled by the instant reach-back capability afforded by modern technology and smartphones, micromanaging behaviors enable loss-averse and career-minded leaders to control their own interests, insisting on zero defects. Remarkably, the U.S. military formalized the rationalization of micromanagement in the Department of Defense’s Joint Publication 1, when the famous paragraph on “centralized control, decentralized execution,” was modified to encourage senior-level leaders to exercise direct control at the tactical level based on the “associated comfort level of the commander.”9 This shift formally undercuts the tried-and-true tenet of “decentralized execution” and empowers micromanaging commanders to rationalize their involvement in things formerly autonomous at far lower levels of leadership.

Goodpaster describes how goal-fixated leaders rationalize poor ethical behavior and detach themselves from responsibility when “competitiveness and goal seeking drive out compassion and generosity, making more serious compromises easier as time goes on.”10 This explains the behavior of the 33 leaders (so far) charged with corruption, bribery, prostitution, or the betrayal of classified port schedules as part of the Glenn Defense Marine Asia (GDMA), or “Fat Leonard,”scandal.11 One such officer, Captain Daniel Dusek, U.S. Navy, blamed the “endemic culture within the Navy in Asia” and charged that Leonard Francis “was able to leverage his way to the top in plain view of generations of senior Naval Officers and Admirals.”12 David Schaus, who was a junior officer when he stood up to the suspected fraud involving Francis, described that, “everyone knew what was going on, and it was accepted as the way it was.”13 In this case, corruption thrived for years at great cost to the Navy because leaders detached themselves from responsibility through the actions of those around them.

Goal Sickness & Collisions

The tragic Fitzgerald and John S. McCain collisions further illuminate the interplay between fixation, rationalization, and detachment. A Government Accountability Office report found that “as of June 2017, 37 percent of the warfare certifications for cruiser and destroyer crews based in Japan—including certifications for seamanship—had expired.”14 Nonetheless, commanders were able to keep their ships on patrol through a program called the Risk Assessment Management Plan (RAMP).15 Formalized by RAMP, Navy leaders, fixated on meeting deployment orders, were able to rationalize their acceptance of incredible risk in lapsed certifications.

The Navy’s “Comprehensive Review of Surface Force Incidents,” commissioned in the wake of the Fitzgerald and John S. McCain tragedies, noted that “under pressure to perform, and feeling ill-equipped to succeed, some leaders can stop listening to their team when feedback appears to detract from their immediate goals . . . crews perceived their Commanding Officer was unable to say ‘no’ regardless of unit-level consequence.”16 The report highlighted this toxic leadership dynamic as a “can-do culture” in the surface warfare community. “Can do,” of course, is a positive term that serves to excuse leaders from a skewed leadership compass—one that cost Navy sailors their lives.

Endemic goal sickness across the Navy points to a gap between leaders knowing what it means to lead and actually being a leader. That is, most leaders in the military know the appropriate actions to take when a challenging situation arises (an issue of competence), yet many continue to make choices that are inconsistent with being moral leaders (an issue of character). This is because character must be deliberately developed and practiced, not simply studied. Just as the service would never expect naval aviators to perform in combat without practice, it cannot expect leaders to make moral decisions without developing and practicing character.

Close the Knowing-Being Gap

The Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) should alter the current NLDF framework to implement “self-reflective” training models to develop character and close the knowing-being gap. Elite education already understands the developmental techniques central to closing this gap, with legendary leadership experts such as Ron Heifetz and Marshall Ganz focusing entire courses at the Harvard Kennedy School on developing the world’s top public servants through iterative, introspective leadership techniques.17 Several companies, including the Granger Network, The Vanto Group, MOSAIC Human Development, and Landmark Worldwide, address the knowing-being gap using a self-reflective approach. Implementing these breakthrough techniques will encourage Navy leaders to confront their past, examine their values, virtues, strengths, weaknesses, and fears, and understand why they are inclined to make malign choices when a character challenge arises. Harvard Business School’s research shows that leaders who experience regular self-reflective training become more committed and authentic leaders.18

The Navy has a solid foundation in developing competence, shown in NLDF 2.0, and competence is reinforced with technical schools and combat readiness standards. Regular, experiential training in character, however, remains aspirational, if not absent from milestone schools. Community leaders must supplement the existing leadership development framework with practice-based, self-reflective training to produce men and women steeped in character-driven leadership skills.

Self-reflective leadership training could be added at all NLDF timeline milestone-school breaks using existing tools at minimal cost. Beyond this, recurrent training will enhance program effectiveness and should be facilitated by contracted providers at times convenient for organizational commanders. It is likely that self-reflective training conducted during division officer and department head time frames also would boost millennial retention.

Build Leaders of Character

Millennials are hungry for leadership development, and these changes in the NLDF present an opportunity not only to improve character, but also retain moral leaders over the long haul. Contrary to negative reports on millennials written by some military leaders, the Navy’s cultural challenges are not the result of the inferior quality of a younger generation.19 Even top-quality organizations must always look for ways to adapt to changing paradigms, and senior leaders must create an environment that attracts, retains, and grows the best young talent possible.

Deloitte’s 2016 “Millennial Survey” analyzed responses from some 7,700 millennials from 29 countries. The report indicated that:

During the next year, if given the choice, one in four millennials would quit his or her current employer to join a new organization or to do something different. That figure increases to 44 percent when the time frame is expanded to two years. By the end of 2020, two of every three respondents hope to have moved on, while only 16 percent of millennials see themselves with their current employers a decade from now.20

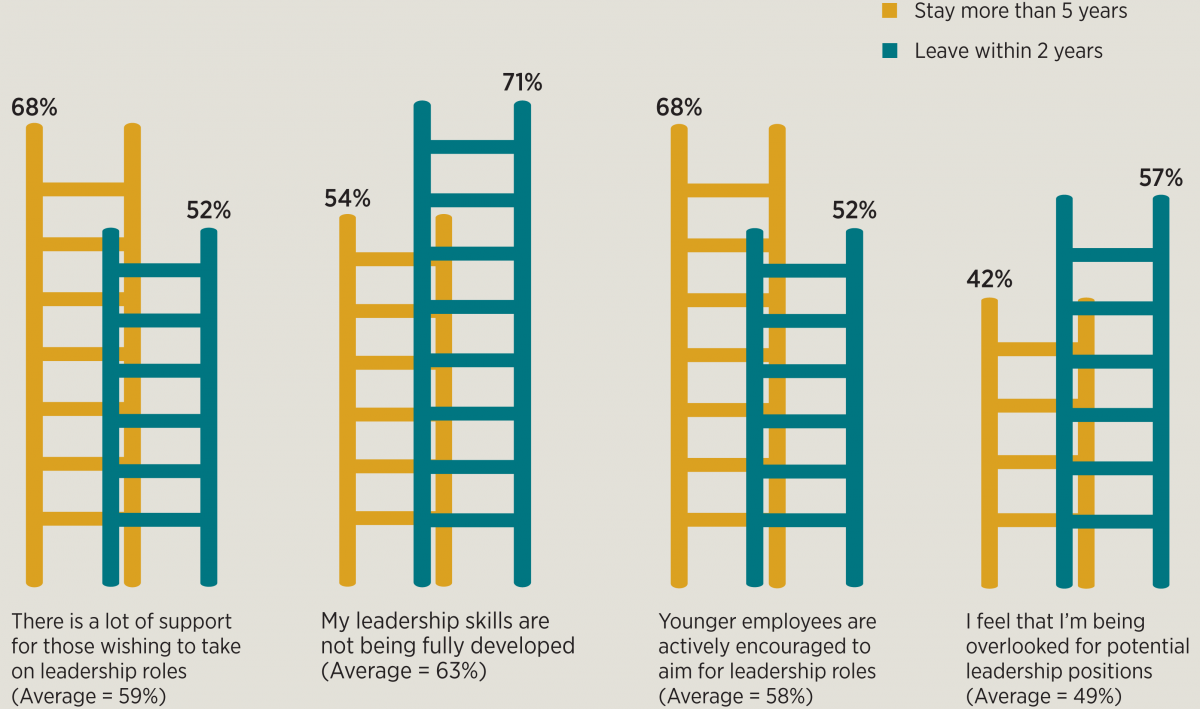

Taken at face value, the survey results appear problematic for an organization like the Navy that aspires to keep young leaders on board for 20 years or more. Deloitte goes on to correlate this millennial-stereotypical lack of loyalty, however, to widespread organizational neglect for personal leader development. Millennials identified leadership as the most valuable skill or trait they can have, but “more than six in ten millennials said their leadership skills are not being fully developed.”21

So, there is a direct correlation between the quality and extent of organizational leadership development and the resultant level of millennial loyalty. The answer to the Navy’s questions of retention and character of leaders might thus be solved with a fundamental shift in how it trains its people.

To eradicate goal sickness and address the long-term retention of talented young leaders, the CNO should supplement the next version of the NLDF with character-centered self-reflective training. Community leaders also should take action now to incorporate experiential, self-reflective training within their respective communities. Just as we would not send sailors into battle firing iron cannons on board wooden ships, the Navy must update its approach to building character in leaders. These retooled leaders will slow the insidious creep of goal sickness, prevent cultural crises, mitigate risk, and inspire institutional loyalty that will usher in a stronger Navy the nation deserves.

1. ADM John M. Richardson, USN, “Navy Leader Development Framework 2.0,” Chief of Naval Operations, www.navy.mil/cno/docs/NLDF_2.pdf. The Navy’s community leads are identified in “NAVADMIN 060/17,” www.public.navy.mil/bupers npc/reference/messages/Documents/NAVADMINS/NAV2017/NAV17060.txt.

2. Kenneth Goodpaster, “Ethics or Excellence? Conscience as a Check on the Unbalanced Pursuit of Organizational Goals,” Ivey Business Journal (March/April 2004), iveybusinessjournal.com/publication/ethics-or-excellence-conscience-as-a-check-on-the-unbalanced-pursuit-of-organizational-goals/.

3. Goodpaster, “Ethics or Excellence?”

4. Kenneth Goodpaster, “Work, Spirituality and the Moral Point of View,” International Journal of Value-Based Management 7, no. 1, 49–62.

5. Goodpaster, “Work, Spirituality and the Moral Point of View.”

6. ADM Harry Harris Jr., USN, “Final Endorsement on Command Investigation into the Circumstances Surrounding a Class Alpha Mishap Involving HSC-6 MH-60S Aircraft, BUNO 167985, Which Occurred At N 22° 34’ 18” E 037° 25’ 29” Resulting in the Deaths of LCDR Landon L. Jones, USN, and CWO3 Jonathan S. Gibson, USN, on 22 Sep 2013,” U.S. Pacific Fleet Official Endorsement, 2014.

7. Goodpaster, “Work, Spirituality and the Moral Point of View.”

8. Guy Snodgrass, “Keep a Weather Eye on the Horizon,” Naval War College Review 67, no 4. (Autumn 2014), 64–92.

9. Compare GEN Peter Pace, USMC, “Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States,” U.S. Department of Defense: Joint Publication 1, 2007, to GEN Martin Dempsey, USA, “Doctrine for the Armed Forces of the United States,” U.S. Department of Defense: Joint Publication 1 2014.

10. Goodpaster, “Work, Spirituality and the Moral Point of View.”

11. Craig Whitlock and Kevin Uhrmacher, “Prostitutes, Vacations, and Cash: The Navy Officials ‘Fat Leonard’ Took Down,” The Washington Post, 20 September 2018.

12. Craig Whitlock, “Leaks, Feasts and Sex Parties: How ‘Fat Leonard’ Infiltrated the Navy’s Floating Headquarters in Asia,” The Washington Post, 23 January 2018.

13. Craig Whitlock, “The Man Who Seduced the Seventh Fleet,” The Washington Post, 27 May 2016.

14. Government Accountability Office, “Navy Readiness: Actions Needed to Address Persistent Maintenance, Training, and Other Challenges Facing the Fleet,” 7 September 2017.

15. David B. Larter, “U.S. Navy Worked Around Its Own Standards to Keep Ships Underway: Sources,” Defense News, 7 September 2017.

16. ADM Phillip S. Davidson, USN, “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents,” United States Fleet Forces Command Official Report 2017.

17. For more on this topic see Harvard Kennedy School course offerings at www.hks.harvard.edu/faculty/ronald-heifetz and www.hks.harvard.edu/faculty/marshall-ganz.

18. Werner Erhard, Michael C. Jensen, and Kari L. Granger, “Creating Leaders: An Ontological/Phenomenological Approach,” Harvard Business School Negotiation, Organizations and Markets Research Papers, 30 May 2013.

19. CDR Darcie Cunningham, USCG, “Millennials Bring a New Mentality: Does it Fit?” U.S. Naval Institute Proceedings 140, no. 8 (August 2014).

20. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, “The 2016 Deloitte Millennial Survey,” www2.deloitte.com/content/dam/Deloitte/global/Documents/About-Deloitte/gx-millenial-survey-2016-exec-summary.pdf.

21. Deloitte Touche Tohmatsu Limited, “The 2016 Deloitte Millennial Survey.”