As the tired submarine skipper squinted through the periscope, he could barely contain his emotions. Lieutenant Commander John A. Scott, commanding officer of the USS Tunny (SS-282), was about to sink his first enemy warship. After a long night of maneuver, the Tunny was in the middle of a Japanese task force. The radar alerted him to three large blips—perhaps two of them aircraft carriers—and Scott sought to get a good attack position. He identified the bigger target as the carrier Hiyō. He had a perfect firing solution at a range of 1,000 yards. He calmly gave commands to prepare to fire.1

This was an opportunity many a sub skipper dreamed of, sitting undetected among slow-moving enemy carriers. It was almost a textbook firing problem, one worked out a hundred times in drills. The Tunny could not miss. Scott focused on the closest carrier and tersely ordered, “Fire one! Fire two!” A slight rushing sound and two torpedoes raced to their target. Scott followed up with two more torpedoes to ensure a hit. The sonar man reported that all four “fish” were running “hot and true.” The skipper then fired four torpedoes at the second carrier.2 The entire crew heard four detonations, then three more. The crew was elated, and Scott dived to avoid the revenge of the escorts.

For students of World War II naval history, this is a famous scene. But the Tunny did not gain a place in history that day. Its weapons were faulty. It merely damaged one of the Japanese ships, losing a wonderful opportunity.

Fiction and science fiction—what author August Cole calls “FICINT”—have gained currency in the military as a way to expand our imaginations about the future.3 For those charged with thinking about the future—which invariably demands an intimate grasp of the past—counterfactual or speculative history can be another route to creativity. What follows is an exercise in “What if?”—combining actual events and data with slight changes to explore an alternate outcome. In this case, the path outlined might have led to an earlier successful campaign of unrestricted submarine warfare and, possibly, a shorter, less bloody war.

The story examines what we know to have happened in light of the possibility that real problems were identified and solved earlier, some even before the war started. Thinking about historical alternatives in this way can help today’s planners choose the right questions to ask, to set the Sea Services on a path to an alternate future.

The Firing Solution

Chief of Naval Operations (CNO) Admiral William Leahy briefed President Franklin Roosevelt on War Plan Orange, the Navy’s concept of war in the Pacific, in late 1936.4

“Admiral,” the President began, “this is a fine plan for fighting the Japanese all by ourselves, but it’s not clear what Japan wants and how we change their actions. What am I missing?”

Leahy responded, “Well, sir, we believe they have to drive south to Indonesia and seize the oil and rubber their economy and military needs.”

The President nodded and noted that the situation called to mind Germany’s U-boat campaign against Great Britain in the Great War. He told the story of his wartime crossing in the USS Dyer (DD-84) in 1918 and how worried the Navy had been about German submarines.5 He added, “It seems important to deny the Japanese their objective as part of our strategy early in any war.6

“If it’s the resources they want and need to sustain their economy and military production, then our plan must seek to deny them that objective,” the President reasoned. He asked about interdicting Japanese commerce before suggesting that submarines do so.

The President instructed the Secretary of the Navy to have the General Board meet soon to discuss submarine designs for use in the Pacific.7 He added, “I hear of a few young Turks with ideas for long-range boats that sound ideal for getting at the Japanese.”

Roosevelt’s questions prompted Navy officers to examine a wider range of scenarios in 1938 and 1939 than planned, to examine how to interdict Japanese merchant marine operations.8 The Navy’s learning system fed these studies and games into the annual fleet problems, where Navy aircraft and ships tested plans and tactics under realistic conditions.9

Exercises

Both President Roosevelt and Secretary of the Navy Claude Swanson attended Fleet Exercise XIX in April 1938.10 Sensing an opportunity to reinforce the service’s ties with the President, Navy leaders planned a live-fire torpedo and dive-bombing demonstration, with three submarines firing simultaneously at a retired battleship. These would be the first live U.S. torpedoes fired in decades.

The President, surrounded by his immediate staff and some press, sat on the fantail of the presidential yacht USS Potomac as the boats fired from a range of 1,000 yards, all three torpedoes running hot, straight, and true.

On the Potomac, Roosevelt leaned forward in his chair. There was one clear splash at the battleship’s armor blister, but no explosion. The President and his party were hugely disappointed. He quipped, “This reminds me of Beatty at Jutland—‘There is something wrong with our bloody ships today.’” He gave a stern look to the CNO.

“Admiral,” the President said, “I think you need to figure a few things out. Please come back and see me when you determine what the problem is.”

After numerous tests at Newport, Rhode Island, over the next six months, technicians identified flaws in the depth-setting and contact-exploder mechanisms that had embarrassed the Navy. By mid-1941, the President had his explanation and the modifications were entering the fleet.11 By December, the U.S. Navy’s weapons were ready for war.

The Navy learning system adapted to policy guidance from the President and incorporated insights from the fleet problems. The results convinced Congress to increase submarine production. Only 38 fleet submarines were operational as of Pearl Harbor in late 1941, but another 74 were on order. Moreover, the skippers of these boats had spent two years refining attack tactics against naval and commercial targets.

Campaigns of 1942–43

Admiral Thomas Hart unleashed the small but lethal submarine force immediately after Pearl Harbor, and the boats began to distinguish themselves right away. The submarine commanders were aggressive and focused on maximizing damage to Japan’s economic lifelines. The tactics developed before the war worked well, and commanders knew how to press attacks relentlessly. As a result, in 1942 the Navy sub force sank 1.3 million tons of merchant and naval shipping— and twice that amount in 1943. The Navy doggedly targeted Japanese oil tankers and the production sites for potential oil carriers to drive up shortages for Japan.

Not everything worked perfectly, however. Despite Navy Captain Charles Lockwood bringing back intelligence from London revealing German and British difficulties with magnetic-influence exploders, problems with the U.S. Mk 14 torpedo’s Mk 6 exploder were not identified until summer 1942. “One shot, one kill” was an enticing goal, but experience—war patrol reports in the first six months of 1942—showed how far from achieving it the subs were. The Navy recalled the exploders in mid-1942.

The submarines were more than commerce raiders; they supported combat operations, including the Battle of Midway. The USS Tambor (SS-198), under Lieutenant Commander John Murphy, sank the Japanese cruisers Mikuma and Mogami on 5 June, prior to the full battle, along with a destroyer that came to their rescue. The Tautog (SS-199) was rewarded two days later when she found a Japanese escort carrier limping along and finished her off with two torpedoes.

Wahoo Triumphant

The USS Wahoo (SS-238), under Commander Dudley “Mush” Morton, slipped her moorings and began her fifth war patrol on 25 April 1943, departing Midway for patrol areas around the Kuril Islands.12 The Wahoo made three successful attacks on 4 May, expending just seven torpedoes. Morton sighted a three-ship convoy and attacked, sinking a large freighter. On the night of 9 May 1943, the Wahoo picked up two fat and unescorted targets on radar, sinking both. In less than two weeks, she conducted ten attacks on eight different targets, disposing of seven vessels comprising 41,000 tons. She ended the war as the Navy’s most successful boat, with more than 155,000 tons sunk.

By the end of 1943, the Japanese had lost 4.2 million tons of merchant shipping. The Silent Service claimed the majority of this success.

Campaigns of 1944–45

By early 1944, losses had reduced Japan’s total merchant tonnage to under 2 million, the estimated threshold below which it could not survive—it could feed its people or sustain an extensive war production effort, but not both. The country was suffering severe shortages. In response, the Imperial government diverted all petroleum supplies to the war effort, but supplies were insufficient to support the many island garrisons or train new pilots.

The end point for the naval campaigns occurred at the Battle of Leyte Gulf in October 1944, history’s largest naval battle. Admiral Takeo Kurita’s powerful Center Force consisted of 5 battleships, 10 heavy cruisers, 2 light cruisers, and 15 destroyers. Kurita flew his flag from the heavy cruiser Atago. The USS Darter (SS-227) and Dace (SS-247) were operating together off Palawan Island, racing together to get ahead of Kurita’s force for an attack. Just before 0650, the Darter fired six torpedoes at the Atago, and got two hits on the cruiser Takao moments later. Not to be outdone, the Dace put four holes into the Maya, the Atago’s sister ship. All three cruisers slipped beneath the waves.13

Later, a “wolf pack” comprising the USS Angler (SS-240; Commander F. G. Hess), Bluegill (SS-242; Commander E. L. Barr), and Bream (SS-243; Commander W. G. Chapple) ambushed Admiral Shōji Nishimura’s Southern Force out of Melgar Bay off Dinagat. The subs sank all Nishimura’s ships, including the battleship Yamashiro. By the end of 1944, the U.S. Navy had effectively eliminated Japan’s naval aviation, merchant shipping, and surface fleet.

The U.S. invasion of Okinawa planned for Easter morning (1 April 1945) was expected to be horrendous. The Japanese commander had hoped to hurl an overwhelming force at the U.S. invasion fleet, including hundreds of kamikazes. Instead, the island was seized by May 20, after several weeks of patient clearing operations.14 The kamikazes were deadly but fewer in number than expected. Fewer than 250 “divine wind” pilots sacrificed themselves, claiming 6 ships sunk and 30 damaged. The Navy lost 490 killed and 1,023 wounded in the battle.15

Japan’s leaders, already in shock from domestic food shortages and the Saipan campaign, and facing the destruction of their homeland, requested mediation in July from Russia and Switzerland to ensure the emperor’s life and reign.

Outcomes

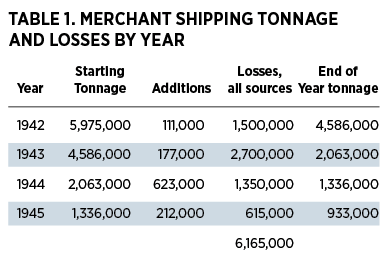

Postwar tabulations revealed that the U.S. submarine force sank nearly 740,000 tons of Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) ships, and nearly 5.8 million tons of merchant vessels over the course of the Pacific war. Of that, U.S. submarines claimed 250 IJN warships and more than 1,300 merchant vessels, about 65 percent of all Japanese ship numbers and 89 percent of the commercial and oiler tonnage (see Table 1). The submarine force started early and decimated the lines of communication connecting Japan with critical energy supplies. 16

No doubt this is why, when Fleet Admiral Chester Nimitz scheduled his change of command, it was conducted on the new teak decks of the USS Menhaden (SS-377). It reflected Nimitz’s appreciation of the Silent Service’s success in the Pacific.17

Lessons

Data in Table 1 is based on reality but accelerates the timeline. Actual losses from 1944 and 1945 have shifted to 1942 and 1943, respectively, with estimates supplied for the counterfactual 1944 and 1945.18

The naval strategists of the interwar period succeeded in discerning the complexities and contours of the next war, despite living in a time of disruptive change. Today’s strategists should study not only their forebears’ insights but also the elements they overlooked.19 In Why Don’t We Learn from History?, strategist B. H. Liddel Hart warned, “Awareness of our limitations should make us chary of condemning those who make mistakes, but we condemn ourselves if we fail to recognize mistakes.”

Speculative history offers lessons that can be framed as questions for today’s force planners:

• What is our theory of victory against great powers? What critical vulnerabilities (e.g., oil tankers) can our forces attack with greatest advantage?

• What critical capabilities do our forces count on? Have they been rigorously tested, including against a “red team”? In other words: What is today’s equivalent of a defective Mk 6 magnetic exploder design?

Does our personnel system ensure that the right leaders are in place? Are we developing innovative leaders like “Mush” Morton, Dick O’Kane, and Gene “Lucky” Fluckey?

Good history should capture more than “who” and “when.” To realize its benefit requires going beyond happenings. As one historian argued long ago, “How can we explain what happened and why if we only look at what happened and never consider the alternatives?”20 By studying key decisions and alternatives to the problems faced by commanders, we can derive meaningful lessons.

The commerce-raiding war the submarines fought was not the one they trained for; adaptation was required.21 A shorter and less costly “silent victory” had been possible, if only the torpedoes had worked right earlier. It is not hard to imagine the implications of a more lethal campaign initiated from the start of hostilities.22

Exercises such as this can help “future proof” strategists’ and planners’ thinking, to build the best naval fighting force possible. Facing the future requires all the insight we can gather to ensure the Navy retains its preeminence on, over, and under the sea.

1. The title of this essay is from Clay Blair, Silent Victory: The U.S. Submarine War against Japan vol. 1, (New York: Lippincott, 1975), 385; USS Tunny War Patrol #1 Report, dated 23 February 1943.

2. Theodore Roscoe, United States Submarine Operations in World War II (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1949), 257; Charles A. Lockwood, Sink ’Em All: Submarine Warfare in the Pacific (New York: Dutton, 1951), 95–96.

3. P. W. Singer and August Cole, Ghost Fleet: A Novel of the Next World War (New York: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt, 2015).

4. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange: The U.S. Strategy to Defeat Japan, 1897–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991).

5. Michael D. Hull, “FDR & His Mighty Navy,” Naval History, February 2019, 34–39.

6. J. E. Talbott, “Weapons Development, War Planning and Policy: The U.S. Navy and the Submarine, 1917–1941,” Naval War College Review 37, no. 3 (May–June 1984), 53–71.

7. John T. Kuehn, Agents of Innovation: The General Board and the Design of the Fleet That Defeated the Japanese Navy (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2008).

8. Joel Ira Holwitt, “Execute against Japan” (Thesis) (College Station, TX: Texas A&M University Press, 2009), 98–147.

9. Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018).

10. In reality, Roosevelt attended Fleet Exercise XX in 1939. Albert A. Nofi, To Train the Fleet for War: The U.S. Navy Fleet Problems, 1923–1940, Newport Papers 18, Newport, RI: Naval War College Press, 2010, 229–36.

11. For the true story of torpedo development, see Anthony Newpower, Iron Men and Tin Fish: The Race to Build a Better Torpedo During World War II (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2006).

12. The attacks described did occur, but very few of the torpedoes actually exploded. Richard O’Kane, Wahoo: The Patrols of America’s Most Famous World War II Submarine (New York: Bantam Books, 1989), 251–71.

13. John G. Mansfield, Cruisers for Breakfast, War Patrols of the USS Darter and USS Dace (Ashford, WA: Media Center, 1997),133–68; Blair, Silent Victory, 726–33.

14. The actual campaign was longer and bloodier, 1 April to 22 June 1945.

15. The kamikazes in fact destroyed 26 ships and damaged 164, with 4,907 sailors killed. George Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power, The U.S. Navy, 1890–1990 (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994), 267.

16. The actual totals were 201 warships and 1,113 commercial ships and 55 percent. Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power, 233.

17. Mansfield, Cruisers for Breakfast, 263–65.

18. The table data imagines only a modest 10 percent total increase in tonnage sunk, but that success comes 18 months earlier. Table derived from Naval History and Heritage Command, “Japanese Naval and Merchant Shipping Losses During World War II by All Causes.”

19. See Mick Ryan, “Submarine Operations in the Pacific,” Australian Defence Journal no. 190 (March/April 2013): 62–75.

20. Hugh Trevor-Roper, quoted in Niall Ferguson, Virtual History, 85.

21. Ian W. Toll, Pacific Crucible: War at Sea in the Pacific, 1941–1942 (New York: Norton, 2012), 252.

22. Clay Blair claimed the torpedo scandal lengthened the war “by many, many months.” Blair, Silent Victory, 361–62.