While serving in the U.S. Army, Colonel Jill Morgenthaler used many lessons from her father, Marine Colonel Wendell Morgenthaler, including following in his footsteps as a second lieutenant in Korea, commanding a brigade, and attending one of the military war colleges. Two lessons in particular, the need for sleep to perform at the highest level and the importance of taking a nap when possible, were ingrained when he recounted his service in Vietnam.

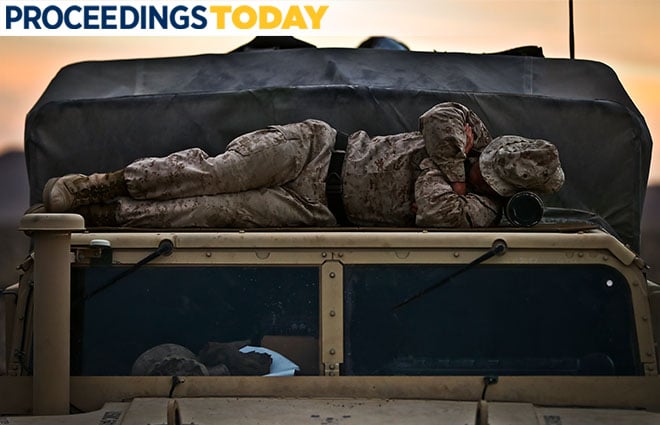

As media contact and troubleshooter for the commanding general in Iraq, the younger Colonel Morgenthaler found sleep was captured when the opportunity presented itself. As the truth unraveled around the 2003 Abu Ghraib prison scandal, Morgenthaler fielded phone calls throughout the night then each morning prepared the general’s 6:00 a.m. briefing. Late afternoon was quiet; the media had published their stories and by 4:00 p.m. she would be exhausted as she headed to work out. Recalling her father’s words, Morgenthaler headed to her hooch for a 20-minute nap to give her energy to work out and rejuvenate before the evening’s media calls.

Living on naps kept her healthy and emotionally in control in what were sometimes volatile situations. When the media frenzy around the Abu Ghraib situation exploded, Morgenthaler remained composed through the continual bombardment of questions and calls.

Chronic Sleep Deprivation on Deployment

The Navy’s “Comprehensive Review of Recent Surface Force Incidents,” which examined the deadly collisions in 2017 of the USS John S. McCain (DDG-56) and the USS Fitzgerald (DDG-62), found that “Fatigue or ineffective fatigue/rest management was embedded in the four key mishaps that occurred in the Western Pacific.”

Because chronic sleep deprivation can put performance, safety, and mission in jeopardy, everyone needs to be self-aware of their fatigue levels and inform leaders if sleep debt is an issue. The Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute survey results from forward deployed ships showed recurrent themes regarding exhaustion, high stress, and lack of sleep. These negative indicators appeared on 21 of the 22 ships based in Japan.1

Sleep is crucial to cognitive thinking, decision making, and reaction time. These are only three of the critical skills one needs to lead optimally, take control of a situation, or safely do one’s job. The Navy collisions of the summer of 2017 makes this clear. Insomnia cases in the military increased 372 percent and obstructive sleep apnea (OSA) cases 517 percent from 2005 to 2014. The greatest increases in insomnia included women and senior enlisted personnel. The greatest rates of OSA included men and senior officers. Individuals more than 40 years of age, African Americans, and Army personnel (compared to those in other military services) are at high risk for both.

In a 2015 interview, former Navy SEAL Stew Smith told ABC News that he “survived for three days on no sleep before the hallucinations started to set in.” After being sleep deprived for 72 hours he recalled “mistaking an airplane for a flying horse, perceiving a bridge as a giant Pez dispenser, and seeing a squat, muscular body builder where there was in fact a fire hydrant.”

Already Returned Home

Military veterans’ sleep problems are particularly common; up to two-thirds of U.S. military troops who served in Afghanistan and Iraq complained of insomnia upon returning home. Throughout recent military history, sleep problems are the number one reason veterans seek medical treatment. Even veterans of earlier conflicts complain about sleep issues; most began during or immediately following their military service. For some, this could translate to 50 years of never having a solid night’s sleep, never fully functioning at top potential.

Many of these sleep impairments also can reduce a veteran's capacity to cope with health-related stressors. Chronic insomnia impairs function and performance across cognitive, emotional, social, and physical domains.2 Short sleep duration and single/combined symptoms of insomnia are associated with an increased risk of hypertension and Type 2 diabetes.3

Memory is aided during sleep where deep sleep appears to be more a dynamic space of consciousness than a completely unconscious state. Recently, research is bringing to light that less time spent in the rapid eye movement (REM) stage of sleep appears to significantly increase dementia risk.4

According to the National Veteran Sleep Survey, a substantial number of veterans report clinically significant insomnia symptoms and are not currently obtaining treatment. “Having trouble falling or staying asleep” was the most frequent reason cited by veterans as a cause of not getting enough sleep (70 percent); 76 percent report they do not typically get enough sleep; and 91 percent are often fatigued during the day.

Physical pain and sleep problems strengthen the relationship between veterans’ PTSD symptoms and aggression toward others. That aggression can have either physical or psychological outlets.

Where to Start?

Like Colonels Morganthaler, naps can be part of your solution. Winston Churchill, Ronald Reagan, Napoleon, Albert Einstein, NASA crew members, air traffic controllers, and Olympic athletes all are known to have used afternoon naps to improve their performance

For many in the military, eight hours of uninterrupted sleep is not a reality. The National Institutes of Health recommends seven to nine hours of sleep for optimal functioning; a nap halfway through the day can refresh cognitive functioning, memory, and energy.

When is the ideal time for a nap? That depends on when the opportunity presents itself. Seven hours after waking is when cognitive decision making, analytic thinking, and energy run dry. Self-awareness and individual schedule, however, are the best indicators. The simplest way is keep track of energy and emotional levels for a week. When do you run out of juice?

Ten to 20 minutes is the ideal length of a power nap. Sleep occurs in five stages; a power nap includes the first two—just enough for a light, restful, restorative sleep. Progressively through awake hours, human performance deteriorates. That deterioration can be prevented by a midday nap part way through the day.

Naps have been shown to decrease impulsivity and supply a greater tolerance for frustration. They can lift productivity and mood, lower stress, and improve memory and learning. In fact, brain activity stays high throughout the day with a nap; without one, it declines as the day wears on. A nap can have the same magnitude of benefits as a full night of sleep.

An afternoon nap is comparable to a dose of caffeine for improving perceptual learning. While caffeine enhances alertness and attention, naps boost those abilities along with enhancing memory consolidation. For many types of memory, the benefits of a nap are substantial, people perform as well after a 60- to 90-minute nap as they do after a full night of sleep. A nap benefits "associative memory" involved in remembering things that are linked, such as putting a name with a face. This suggests that sleep can boost a person’s capacity for learning.

The German military has developed a sleep coaching program for implementation prior to deployment. Objective and subjective sleep quality improved significantly with this program.5 Coaching is done prior to deployment before sleep debt is a problem. In the U.S. military, sleep education or coaching could be done with other critical training. The optimal time to learn and create habits is when in a full learning mode before the challenges have presented themselves.

1. Department of the Navy, “Comprehensive Review Of Recent Surface Force Incidents,” 26 Oct 2017.

2. June J. Pilcher, Allen I. Huffcutt, “Effects of Sleep Deprivation on Performance: A Meta-Analysis,”Sleep 19, Issue 4, 1 June 1996, pp. 318–26.

3. Yanping Li, Xiang Gao, John W. Winkelman, “Association between sleeping difficulty and type 2 diabetes in women” Diabetologia 59, Issue 4 (April 2016), pp 719–27. Lin Meng, Yang Zheng, Rutai Hui, “The Relationship of Sleep Duration and Insomnia to Risk of Hypertension Incidence: A Meta-Analysis of Prospective Cohort Studies,” Hypertens Research (Nov.2013).

4. Matthew P. Pase, Jayandra J. Himali, Natalie A. Grima, Alexa S. Beiser, Claudia L. Satizabal, Hugo J. Aparicio, Robert J. Thomas, Daniel J. Gottlieb, Sandford H. Auerbach, Sudha Seshadri, “Sleep architecture and the risk of incident dementia in the community,” Neurology 89, no. 12 (Septemper 2-17), 1244–50.

5. Heidi Danker-Hopfe, Jens Kowalski, Michael Stein, Stefan Röttger, Cornelia Saute, “Development, Implementation, and Evaluation of a Seep Coaching Program for the German Armed Forces,” Somnologie (2018).

President of Optimal Edge Performance, Ms. Vyskocil is board certified in neurofeedback. She merges neuroscience with leadership training to cultivate resilience and optimal functioning. Designing training protocols based on the brain and body’s response to challenges, she is an expert on the impact of sleep and stressors on performance and health.