Rethinking the Naval Academy Curriculum

(See, W. Wolff, Proceedings Today, April 2018 Proceedings)

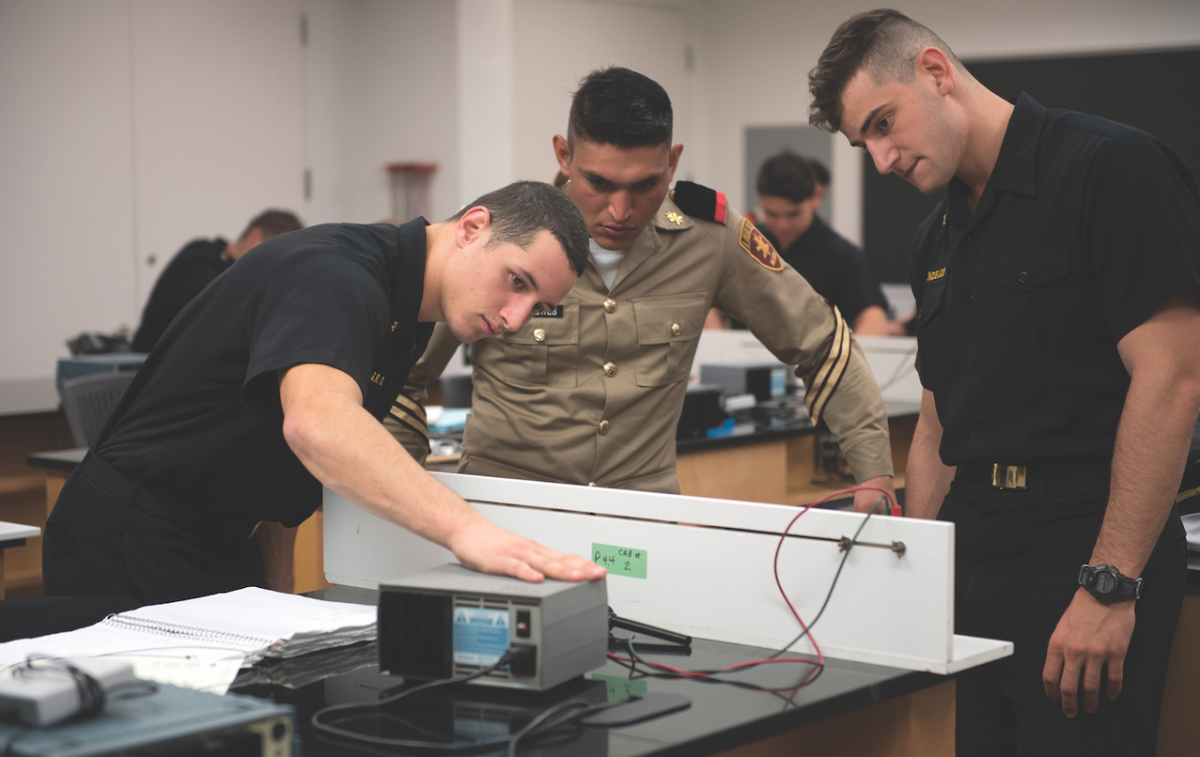

Midshipman First Class Wolff asserts that the two most important tenets of naval officership are “writing and critical thinking” and concludes that these skills are “best developed through an education in the humanities.” He describes some ways in which education in history or world religion may help an officer effectively lead his or her sailors and recommends changing the U.S. Naval Academy’s core curriculum to emphasize the humanities by removing “excess STEM [science, technology, engineering, and math] courses” such as calculus, chemistry, or physics.

I do not write to disparage the value of a humanities education. The humanities are worthy and necessary fields of study, and officers who pursue education in those fields provide crucial perspectives to the Navy. However, I must strongly disagree with the assessment that a STEM education does not teach the critical-thinking, writing, management, and problem-solving skills required to be an effective naval officer.

The essential feature of an education in STEM is not the memorization of theorems, equations, or coefficients. Rather, it is the use of the scientific method, which is at its core a process for identifying and examining bias (one might call this process “critical thinking”). It is the reduction of problems to first principles with broad applications.

Consider the observe, orient, design, act (OODA) loop, a staple of professional education courses for decades. Any engineering student immediately will recognize in it the closed feedback loops first described by James C. Maxwell a century before Col. John Boyd wrote.

Education in STEM develops leadership skills, as engineers leverage the diverse skill set of a design team and practice weighing competing priorities. Writing skills are developed with an emphasis on concise and objective communication. Engineering courses are not a relic of the age of coal, because a STEM education is not about turning wrenches or soldering wires—it is an education in problem-solving.

—Ensign Nicholas Skeen, U.S. Navy

Tactical Nuclear Weapons Are Back

(See A. Howard, pp. 48–53, April 2018 Proceedings)

When I was a first lieutenant, I was assigned from 1958 to 1961 to a Western European–based tactical fighter wing whose primary mission was being prepared to attack targets in Eastern Europe with nuclear weapons. This wing, like others in Europe at that time, was equipped with F-100D tactical fighters armed with Mark 12 nuclear weapons that had the yield of the bomb dropped on Hiroshima in 1945. We always had fully armed aircraft on 15-minute alert, 365 days a year. In the spring of 1961, our wing received Mark 28 nuclear weapons with four selectable yields, three of which were substantially greater than the Mark 12. Strategic Air Command B-52s also carried this bomb.

Lieutenant Howard doesn’t address

directly the employment of nuclear weapons by tactical fighters in her analysis, but they were a major component of President Dwight Eisenhower’s build-up of European nuclear forces and remained so for the duration of the Cold War. She argues that “tactical nuclear weapons” (TNWs) would allow for a shift from a strategy of deterrence-by-punishment (read “mutual assured destruction”—MAD) to one of deterrence-by-denial. She asserts that the use of these weapons to blunt a Soviet ground force attack in Europe likely would not have caused a disproportionate Soviet strategic response against NATO targets.

A close examination of the role of tactical fighters in U.S. nuclear forces in Europe would show that they were postured for an initial rapid response that in no way could be classified as tactical.

Contrary to the title of the article, I submit TNWs aren’t “back”—they never existed. I would suggest that, regardless of a weapon’s yield, once the nuclear genie is out of the bottle you would never get it back in. I agree with Secretary of Defense James Mattis’s sentiment (quoted by Lieutenant Howard) that there is no such thing as a tactical nuclear weapon and that the employment of any nuclear weapon is a game changer.

So where would that leave us in today’s world of additional nuclear threats? Not much has changed. As dangerous as MAD was, it seemed to work pretty well as a nuclear deterrent considering what eventually came through the Fulda Gap in 1989: not the Soviet First Guards Tank Army, but East German shoppers in their plastic cars!

—Major General William A. Gorton, U.S. Air Force (Retired)

What Happened to Our Salty White Hats?

(See C. Fuss, p. 55, May 2018 Proceedings)

One needs to look no further than page 32 of the May Proceedings to see how far the white hat, that once-signature part of the enlisted uniform, has fallen.

More than 50 years ago, at the start of the Vietnam War, I enlisted in the Naval Reserve. I spent one year attending monthly meetings ahead of two years on active duty at Naval Station Subic Bay.

At our first monthly meeting as brand-new reservists, we were issued our uniforms. A chief instructed us on the preconditioning (washing in a sugar water solution, then letting it dry), rolling, and shaping of the white hat. We also were instructed on how it was to be worn.

Somehow this information no longer seems to get passed. I believe it is imperative that it be reinstated, so that when dress blues (or whites) are worn along with the white hat it shows what and who we are—the finest Navy in the world manned by the very best sailors.

—Douglas Halliday, former Petty Officer Third Class, U.S. Navy Reserve

A Mistake Should Not Kill a Sailor’s Career

(See E. Heck, pp. 14–15, December 2017; D. Bolgiano, p. 8, January 2018; J. McCandless, p. 86, February 2018; M. Coughlin, p. 89, March 2018 Proceedings)

As a young sailor on the USS Long Beach (CGN-9) in the very early 1970s, I managed to get into serious difficulty while on a Manila port visit. Being a college graduate and a nuclear- trained machinist’s mate second class, I was the same age as many of the junior officers (JOs). On the last night in port, one of the JOs and I went to the jai alai matches. The country had a curfew in effect, so we stayed at a hotel by the bay that night. The hotel wake-up service was less than reliable, and we missed ship’s movement the next morning. A few days later we flew from the USS Hancock (CVA-19) back to our ship. The JO drew 45 days in hack, and I got 60 days of restriction. Fortunately, we went back into the Tonkin Gulf for 75 days.

Later in my career, I went to Officer Candidate School and was converted to a submarine strategic weapons officer. I retired as a lieutenant commander. The officer went on to become a captain and a destroyer squadron commander.

We met a few years ago after not seeing each other for 40-plus years. Comparing notes, we had to laugh because over the years we had told our troops that we were “the only naval officer who they had ever met that missed ship’s movement in a foreign port and were there to tell them about it.” I strongly doubt that could happen today.

—Lieutenant Commander Fenton T.

McGonnell III, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Know Your Enemy. Know Yourself.

(See K. H. Moghaddam and J. Schoch, pp. 58–63, April 2018 Proceedings)

Commander Moghaddam and Mr. Schoch offer a clear example of why the naval intelligence community continues to struggle in its core mission of providing maritime operational intelligence to the fleet. For the past two-plus decades, the lack of peer maritime adversaries has allowed naval intelligence to focus on issues outside its core competency. With the maritime challenges of China, Russia, and other emerging peers, that slack no longer exists.

The authors characterize Maritime Operations Centers (MOCs) as “overwhelmed and preoccupied with a huge amount of maritime-centric information focused primarily on the here and now.” Describing the “here and now” is only the opening argument of operational-level intelligence analysis. Making sense of data about adversary maritime forces is the fundamental mission of a MOC’s Maritime Intelligence Operations Center (MIOC). Developing a nuanced understanding of the maritime environment and turning that understanding into patterns and predictions for the future is the special challenge that MIOCs face supporting fleet actions at the operational level.

To develop an operationally useful view of the future, professionals in the MIOCs conduct all-source analysis and fusion. Such analysis is not, as the authors suggest, only “completed at large intelligence centers . . . geographically separated from the number fleet commanders.” It is the lifeblood of naval intelligence from the largest intelligence centers to a lone intelligence specialist afloat, consistently identified in our community guidance and selection board precept language as a fundamental competency.

The integration of intelligence and operations is neither new nor transformative. While the authors characterize this approach as an outgrowth of the Naval Special Warfare community, it is really a rediscovery of a best practice that was one of the lessons our mentors taught my generation in the closing days of the Cold War. It is the reason that the operational and intelligence planners at Pacific Fleet headquarters share the same spaces and information access, owning the process together from concept to assessment. “Deep penetration of the customer” is as critical as “deep penetration of the adversary.”

Finally, the authors’ discussion of the challenge of predicting geopolitical events such as a potential coup in Turkey omits the obvious point that such issues are addressed by large elements of the intelligence (and diplomatic) communities. European Command, its Joint Analysis Center, the Defense Intelligence Agency (to whom naval attaches report), and a host of other national agencies have a piece of this question.

To serve a fleet commander, the MIOC needs to be tied—intimately—to these partners and deeply versed in the indicators and signals they are monitoring. Trying to recreate them in the fleet, however, is a costly use of resources that should be devoted to the questions that no one else in the intelligence community is positioned or tasked to address: the trends, operations, and potential actions of maritime adversaries.

—Captain Dale C. Rielage, U.S. Navy

Reach the 21st-Century Sailor

(See P. Osbourn, pp. 16–17, April 2018 Proceedings)

The Navy Is Unprepared for Analog War

(See J. Panter, p. 13, April 2018 Proceedings)

Mr. Osbourn’s proposal for expanded use of social media tools is interesting, but complicated and misguided. It essentially relies on two assumptions: on-demand connectivity afloat; and the suitability of commercial solutions for shipboard environments. Both concepts are dangerous if not properly assessed and implemented.

As a plankowner information professional (IP), I have spent much of my career since October 2001 working to ensure that critical command-and-control paths are planned, allocated, provisioned, and secured to enable worldwide fleet operations. The available bandwidth afloat and the associated data transfer rate are minuscule compared with those of fiber-optic connections on shore. Satellite transport paths must be carefully managed to ensure the prioritized exchange of operational traffic. This typically results in the restriction of popular services such as video streaming.

One may counter that this improves continually through emerging technology; my current carrier strike group enjoys throughput roughly ten times that typical for my 2001 battle group, and Global Broadcast Service (GBS) now offers a large receive pipe for a variety of products. Shipboard business processes, from administrative to medical to logistics, largely now are web-based. Yet this is ultimately a procedural and a technical problem. But what happens when larger satellite paths are not available, either through adversary action or self-imposed tactics? Those processes slow to a near- or complete halt.

Another problem arises with the assumption that commercially designed information technology (IT) products and services may be used in a naval environment without further consideration or risk mitigation. A prime example is the prohibited—but common—use of USB ports on government workstations for the charging of personal smart phones. There is nothing inherently wrong with charging a device through a USB port; it’s designed to work that way. There is something fundamentally wrong, however, with ignoring government IT baselines, information assurance measures, and configuration management solely for user convenience.

Consider also the example of wireless (e.g., cellular, WiFi, Bluetooth) devices on board ship. The electromagnetic spectrum must be managed rigorously afloat, for both operational security and the safety of personnel and equipment. Doing so has grown immensely more difficult with the widespread use of personal wireless devices. Any initiative that would involve expanded use of sailor smart phones would have to take this into account.

This is not the broadside of an old salt who wants to revert to simpler times. I’ve deployed before shipboard email existed, and I don’t want to go back. This is a plea for a balanced approach to a complex problem. Properly engineered IT solutions offer tremendous advantages, from simplifying work to creating better quality of life for our sailors. But new approaches must take into account operational priorities, transport, and security—not as an afterthought, but first. Those factors are more important than keeping sailors from having to read technical manuals.

Finally, it was fun to read this article just three pages after “The Navy Is Unprepared for Analog War.” While it did not appear to be presented as a unified pro-con exchange, it was good to read differing views.

—Captain Vince Augelli, U.S. Navy, Information Warfare Commander, USS Ronald Reagan (CVN-76)

Reading Mr. Panter’s article reminded me of many personal experiences during my active-duty days and some more recent days at sea. I find it curious that many and maybe all U.S. Navy ships are equipped with numerous signal lights, since the Navy no longer teaches Morse Code and disestablished the signalman rate many years ago. Although I suppose quartermasters or other bridge watchstanders can operate these lights, at best they must be learning Morse Code on their own and probably have only minimal training in their operation. On board a nuclear aircraft carrier for a Tiger Cruise four years ago, I attempted to activate a bridge wing signal light, but it was inoperable and appeared to be unmaintained. This ship-ship communication capability seems to have been lost.

The move from the high-frequency (HF) communication system toward an all-satellite setup always has seemed shortsighted. The Navy and the country paid a heavy price in the 1980s when a primary encryption system was compromised by the espionage of the Walker brothers. Antisatellite weapons—kinetic and others—as well as Russian and Chinese future offensive cyber operations could have a similar net effect by disrupting long-haul communications indefinitely since there currently is no HF backup. Although ships are equipped with tactical HF systems, these are not designed for ship-shore comms, the radiomen (RM) who were trained to carry out this task have gone the way of the signalman, and the shore HF-radio infrastructure is now history. The last remaining three towers from Radio NSS on Greenbury Point in Annapolis are now navigation aids only.

That said, kudos to the Navy for reinstituting celestial navigation training. Hopefully, the surface warfare officer (SWO) program revamp includes the requirement for a “day’s work in navigation” for all current and aspiring SWOs.

I agree with Mr. Panter’s assessment about the potential vulnerability of sole dependency on digital technology systems when alternatives are known and available. The Navy needs a plan B to use them to avoid digital technology single-point failures.

—Captain Alan Swinger, U.S. Navy

(Retired)

Amphibs in Sea Control and Power Projection

(See J. D. Caverley and S. J. Tangredi, pp. 18–22, April 2018; S. Tangredi, p. 11, and T. Murphy, p. 160, May 2018 Proceedings)

With regret—because of my admiration for the authors—I must take strong exception to several of Dr. Caverley’s and Captain Tangredi’s points.

First, the authors say that “the Navy prevented the Soviets from brining more missiles into Cuba during the 1962 Cuban Missile Crisis,” a misleading statement. The U.S. Navy had failed to detect or stop the delivery of scores of strategic and tactical missiles to Cuba, as well as several Il-28 “Beagle” light bombers, not to mention 128 nuclear missile warheads and 6 bombs that were carried to the island by sea. (A Soviet merchant ship with another 24 nuclear missile warheads was in port, but was not unloaded.)

Second, there is no “reemerging Russian ocean-going fleet.” Almost all surface combatants completed in Russian shipyards during the past decade have been frigates, albeit very capable ships. While highly innovative Russian submarines have been designed, construction is far behind schedule. The country’s only aircraft carrier is in the Severodvinsk shipyard for rehabilitation and modernization, a three-year or longer process. There is talk of building carriers in the future, but that is not yet a viable program.

The estimated cost of the America- class LHAs is approximately $3.4 billion per ship. Thus, for the cost of one Gerald R. Ford–class nuclear aircraft carrier (CVN)—almost $15 billion per ship—the Navy could procure four or more LHA/LHDs. Indeed, analysis shows that by skipping the construction of one CVN and committing to multiple-ship procurement, the Navy could buy at least five LHAs/LHDs for the same cost. Each could operate 20 or more F-35B fighter-attack aircraft plus helicopters, with some 1,800 Marines embarked.

The question should be asked of combatant commanders: Would each prefer another CVN (with 60 or 70 high-performance aircraft) or five (or possibly six) LHA/LHDs (carrying as many as 100 to 120 F-35Bs)? This proposal goes beyond the current buy for the amphibious role; these additional ships will provide significant capabilities regardless of their label—CVL, LHA, LHD, or even SCS (sea control ship).

The issues facing the U.S. Navy today are serious and their resolution will impact the fleet for several decades. More accurate and more serious discussions are required.

—Norman Polmar

Editor’s Note: The article erroneously stated that the cost of the USS Tripoli (LHA-7) was approximately $10 billion. That figure covers the cost of all three America-class amphibious ships (LHA-6 through LHA-8). The online version of the story has been corrected.

Overuse Devalues Personal Awards

(See P. Kingsbury, p. 14, March 2018; B. Tillman, p. 10, April 2018; R. Allison, p. 162, May 2018 Proceedings)

While it will not solve Fleet Master Chief Kingsbury’s problem of overuse or Barrett Tillman’s of gaudy display of personal awards, there is a way that individuals can bring subtlety and a touch of class to their uniforms—wear only one row.

I was pleased a few years ago to see a photo of three Navy admirals at the Pentagon wearing single rows. Unfortunately, the idea has not caught on. Put next to Army or Air Force uniforms with all their gewgaws, naval uniforms are more distinguished in their simplicity.

Let’s make this more so. A specialty badge and a single row of color are more than enough. Seeing only three at a time may also get people learning what the ribbons signify.

— Commander Robert R. Powell, U.S. Navy (Retired)

ERRATUM

In the May Proceedings we identified the Chilean Chief of Naval Operations as Fleet Admiral Enrique Larrañaga Martin. The current Chief of Naval Operations of the Armada de Chile is Admiral Julio Leiva Molina.