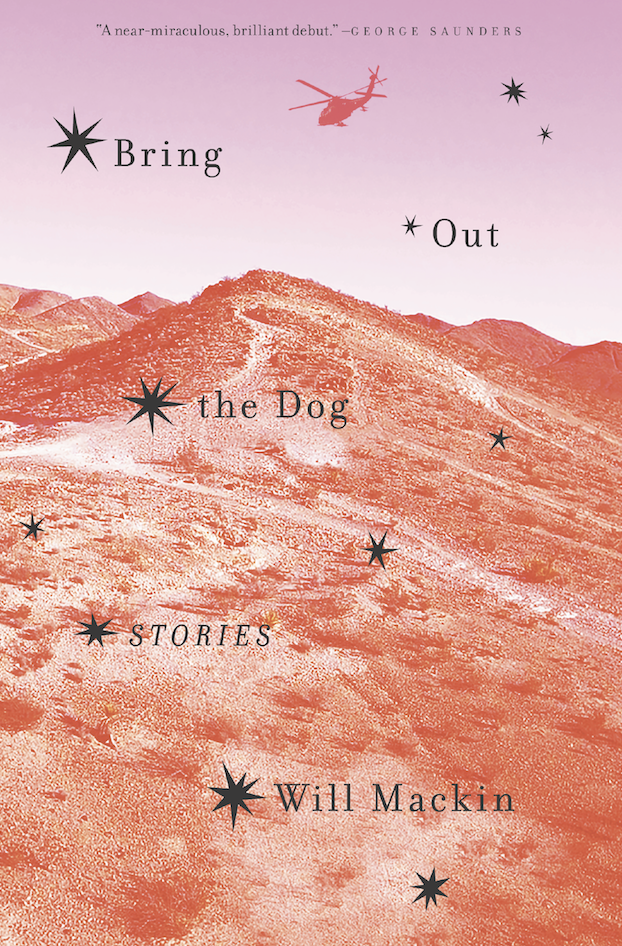

Will Mackin. New York: Random House, 2018. 173 pp. $27.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Jarrod Suess, U.S. Navy

“Soon enough, their noise became a memory; then that memory faded.” This line is the essence of Will Mackin’s lurid work of fiction Bring Out the Dog. Every soldier—no matter the style of war—suffers from the loss of memory. Not some sort of amnesia, either. Instead, our “concept of history” (as the German philosopher Walter Benjamin put it) is mostly illusory. We choose how we want to see it. Mackin brilliantly gives his concept of history and his version of truth in this book.

“Soon enough, their noise became a memory; then that memory faded.” This line is the essence of Will Mackin’s lurid work of fiction Bring Out the Dog. Every soldier—no matter the style of war—suffers from the loss of memory. Not some sort of amnesia, either. Instead, our “concept of history” (as the German philosopher Walter Benjamin put it) is mostly illusory. We choose how we want to see it. Mackin brilliantly gives his concept of history and his version of truth in this book.

The mise-en-scène of Bring Out the Dog is this: anecdotally drop the reader into the mind of a soldier training for war and directly into battle. It is a splash of cold water in the face, and through this prism readers find themselves gazing into the bizarre and the absurd. This might not be everyone’s cup of tea, as it might seem a bit incongruous. But for anyone who has felt war, it is real—whatever that word means. Perhaps the fact that I am teaching Virginia Woolf at the time of this writing also is influencing how I see this work, but this is why I tell my students fiction matters. Literature gives the human reading it a better understanding of themselves, as memories inevitably fade.

Mackin gives readers insight into a fraternity that is often misunderstood, so readers looking for clarity over mythology or gossip will enjoy this book. In the story “Welcome Man Will Never Fly,” the protagonist contemplates committing an unethical act by forging some documentation in his story The character resolutely proclaims, “Reed and I were brothers—by fire, not blood—and I wanted what was best for him.” For people who have not been to war, it may seem like a no-brainer to avoid this type of unethical situation. But Mackin gives us a confounding trauma-forged relationship. The character quite literally will do anything for his so-called brother. The moment is powerful because it only matters how his main character remembers the past and understands his relationship with Reed, not the institutional expectation of what their relationship should be.

In “The Lost Troop,” Mackin uses intertextuality by inserting Pink Floyd’s “Another Brick in the Wall (Part 2),” giving a more profound meaning to the story. Indeed, it is the strangest moments and images—and music—soldiers remember upon returning from war. There is nothing facile about Mackin’s use of Pink Floyd. He amplifies the fact (which all soldiers know) that there is a particular kinship between music and war, because music helps people remember—there is a soundtrack.

If you have ever wanted to step into the mind of a soldier who has faced perpetual war, dare so at your own risk, but then pick up this book. This debut work of short stories offers quick snapshots of time of a long life lived. Each vignette crooks a finger toward the reader, inviting them to peer into a tiny window of truth. While I preferred some stories to others, much could be made of Mackin’s arrangement of the stories. Their juxtaposition was incredibly linked; in a way that the reader yearns to connect them—to make sense of it all—but you cannot because it is messy; and I like it that way.

Lieutenant Suess is a Navy SEAL and is in his second year teaching at the U.S. Naval Academy as an instructor in the English Department. An 18-year Navy veteran who has served overseas numerous times, he earned his master’s degree in English from Georgetown University in 2016, with a focus on American modern literature.

John Lewis Gaddis. London: Penguin Press 2018. 384 pp. Notes. Index. $26.

Reviewed by Lieutenant Brendan Cordial, U.S. Navy

John Lewis Gaddis is a Pulitzer Prize winning biographer, professor of history at Yale, and a former Naval War College instructor. He, along with renowned British historian Paul Kennedy, teach a year-long “Grand Strategy” seminar to Yale undergraduates. His recently published On Grand Strategy is a distillation of that seminar. Through diverse historical case studies, Gaddis crystallizes the seemingly nebulous notion of grand strategy “as the alignment of potentially unlimited aspirations with necessarily limited capabilities.” The book is an excellent introduction to valuable case studies, thinkers, and principles of grand strategy.

Billed as a “master class” in strategic thinking, the book details the major themes and principles of successful grand strategists. Gaddis frames the work within the thinking of the 20th-century academic Sir Isaiah Berlin and his influential essay “The Hedgehog and the Fox.” Taking from a passage written by the ancient Greek poet Archilochus of Paros, “The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing,” Berlin categorized great thinkers and writers throughout history as either hedgehogs or foxes. Gaddis employs this hermeneutic to bin leaders throughout history in case-study analyses for lessons in the balancing necessary for executing a successful grand strategy.

Gaddis proceeds roughly chronologically comparing leaders during influential periods in world history. Departing from the Hellespont, Gaddis covers some 2,500 years of grand strategy, discussing in detail Master Sun Tzu, Pericles, Octavian, Mark Antony, St. Augustine of Hippo, Machiavelli, Philip II of Spain, Elizabeth I of England, Napoleon, Clausewitz, Douglas, Lincoln, Tolstoy, Wilson, and FDR. Although Gaddis necessarily presents only a survey of the historical context, he deftly gleans from each case study the critical lessons applicable to students of grand strategy.

My only criticism of the book is its sometime rambling or seemingly diversionary comments that likely would prompt discussion in a classroom setting but left me befuddled as a reader. Particularly in the St. Augustine/Machiavelli and Philip II/Elizabeth I chapters, Gaddis seems distracted by various contemporary philosophical or theological issues that do not relate directly to the lessons pertinent to modern students of grand strategy. While many appreciate the timeless debate seeking to reconcile the notion of legitimate human free will with a belief in an omnipotent, omniscient God, such a discussion seems beyond the scope of the book and, regardless of one’s conclusion, of little utility in deriving lessons for future grand strategists.

Despite this minor reservation, I encourage history buffs, defense professionals, and current/future grand strategists alike to read (and reread!) Gaddis’s On Grand Strategy. In our increasingly bifurcated politics, specialized academics, and stove-piped professions, On Grand Strategy is a reminder that history has tended to punish absolutists and specialists—pure hedgehogs or foxes fail to proportion ends and means effectively. The complexity of human and state relationships and interrelationships that form the working substance of grand strategy require both the lofty idealism of the hedgehog and the tactical efficiency of the fox to be effective.

Lieutenant Cordial is currently assigned to the staff of the Chief of Naval Operations, Surface Warfare Division. He has served on board the amphibious assault ship USS Iwo Jima (LHD-7) and the guided-missile cruiser USS San Jacinto (CG-56).

The Mirror Test: America at War in Iraq and Afghanistan

John Kael Weston. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2016. 624 pp. Sources. $17.

Reviewed by Colonel Chris Graves, U.S. Marine Corps Reserve

For seven years, Kael Weston served on the frontlines of the Marine Corps’s fight in Fallujah, Iraq, and Helmand, Afghanistan, as the Department of State embedded political advisor (PolAd). With a front-row view of on the intersection of strategic policy and its tactical implications, Weston enjoys a unique perspective on these seminal fights of the modern Marine Corps. The Mirror Test, his exhaustive look at these wars, serves as more than an epic saga from an important witness. Weston lends an important human dimension to the Marines, Iraqis, and Afghans embroiled in the United States’ seemingly failed efforts.

For seven years, Kael Weston served on the frontlines of the Marine Corps’s fight in Fallujah, Iraq, and Helmand, Afghanistan, as the Department of State embedded political advisor (PolAd). With a front-row view of on the intersection of strategic policy and its tactical implications, Weston enjoys a unique perspective on these seminal fights of the modern Marine Corps. The Mirror Test, his exhaustive look at these wars, serves as more than an epic saga from an important witness. Weston lends an important human dimension to the Marines, Iraqis, and Afghans embroiled in the United States’ seemingly failed efforts.

Unique among State Department Pol-Ads, Weston’s experience was not from the isolation of the Green Zone of Bagdad or the sterile disconnection of Kabul and ISAF headquarters, but from the tactical headquarters in the middle of the fight. In such position, Weston enjoys a close connection to the Marines carrying the fight and the community in which the fight unfolds. The reader witnesses through Weston’s struggles the very difficult work of counterinsurgency.

Weston unabashedly shines a positive light on the ethos of the Marine Corps in these difficult fights, celebrating their resiliency and endurance in difficult circumstances. His sympathetic portrayal of Colonel, and later General, Larry Nicholson’s leadership in both fights serves as a poignant witness of this Marine’s great accomplishment. Weston personalizes Nicholson’s reservations in these difficult decisions, highlighting a human dimension of the man at the forefront of these fights. Readers see the hefty toll such gravitas weighs upon even hardened warriors such as Nicholson.

Weston struggles with the tragic consequences of these U.S. fights, not only with the Marines lost, but also with the loss of Iraqis and Afghans who endeavored to rebuild their communities. He carefully recognizes the restraint of the Marines in this counterinsurgency, and shares perspective on the difficulty behind every decision. The author himself is tortured throughout the book over his decision during the Iraqi elections wherein 31 Marines lost their lives in a helicopter accident. This decision imprisons Weston in guilt for years to come, inspiring a lengthy search for resolution that fails fruition, but lends human perspective on two long wars.

Weston likewise invests this introspection on the toll suffered by those who cooperated with U.S. efforts to rebuild in the shadow of war. His heartbreaking story of a Fallujah City Counsel leader gunned down for his efforts stands as a beautiful tribute to a brave Fallujan. Weston devotes many pages to these Iraqis and Afghans who risked everything, and so often lost, to lift their communities. His artful vignettes and touching examples beg the reader’s empathy to their plight and highlight the less-covered tragedy surrounding war. Weston endeavors that their sacrifice not be lost to obscurity, and challenges readers to a conscious mirror test; this is his resolute entreaty.

Weston spares no quarter for the politics behind these two wars, but does not dwell on the subject. We know his opinion, but this does not consume the narrative. Weston is more interested in remembering the Marines and civilians than lecturing on the folly behind the loss. The Mirror Test is about the people and the cost of our wars and is very much a cathartic exploration by the author

Colonel Graves is an infantry officer who has served in both Fallujah and Afghanistan.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY BOOKS

By Captain William Bray, U.S. Navy (Retired)

Great Powers, Grand Strategies: The New Game in the South China Sea

Great Powers, Grand Strategies: The New Game in the South China Sea

Anders Corr, ed. Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018. 306 pp. Index. $34.95.

The central focus of these ten essays on the South China Sea rests on one assertion: it is time to stop thinking about the South China Sea dispute in an international law context and focus on what it actually is—a competition of grand strategy between great powers. Plenty has been and will be written about the legal dispute over competing sovereignty claims. But this seems an academic discussion now, especially after the major claimant, China, in 2016 refused to recognize a Permanent Court of Arbitration decision rejecting Beijing’s expansive claims. The first three essays deal with China’s basis for its claims and both its grand and maritime strategies. An essay on the Association of Southeast Asian Nations follows, and then two essays on U.S. strategy; one on its evolution and the other on rebalancing for a Pacific century. The last four essays cover the strategies of Japan, India, Russia, and the European Union, rounding out a welcome and refreshing look at this seemingly intractable problem.

When Proliferation Causes Peace: The Psychology of Nuclear Crises

Michael D. Cohen. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press, 2018. 235 pp. Biblio. Index. $34.95.

The more often new nuclear weapons states approach and then retreat from the brink of annihilation, the more stable and peaceful the world will be. At first blush this is a counterintuitive, if not slightly crazy, proposition. But that is exactly what Michael Cohen concludes. Cohen is a political scientist, not a psychologist, but he relies on years of psychological research to identify patterns of foreign policy choices of new nuclear powers. In keeping with the “availability heuristic,” their leaders initially are overly influenced by their country’s newfound nuclear destructive power, and not by what they do not know well enough—the adversary. The Soviet Union’s Nikita Khrushchev initially undertook an aggressive foreign policy of nuclear assertion. But in the buildup to potential nuclear war, he learned more and became more influenced by the human emotion of fear. Cohen applies this availability, learning, fear (ALF) model in analyzing Khrushchev and Pakistan’s Pervez Musharraf. The book probably will be music to the ears of nuclear weapons proponents, but nonproliferation advocates still have one powerful line of argument, namely, the historical data set is too small to reach definitive conclusions.

Six Days of Impossible: Navy SEAL Hell Week, a Doctor Looks Back

Robert Adams. Victoria, British Columbia, Canada: Freisen Press, 2017. 197 pp. Illus. $14.99.

When Robert Adams graduated Navy SEAL training in 1975, the words “Hell Week” meant nothing to almost anyone outside the military special warfare community. Today, after countless books, articles, and movies, this crucible of Navy SEAL training is practically a staple of American pop culture, routinely appropriated by everything from sports franchises to businesses to describe some professional winnowing process (and doing the real Hell Week a gross injustice). Adams, who transferred to the Army to attend medical school after serving 14 years as a SEAL, presents a day-by-day account of Hell Week through the recollections of the ten classmates with whom he graduated. While it is nearly impossible to add anything original to the SEAL training literary industry (memoirs, fitness routines, novels, management theory as learned at BUDS, etc), Adams at least takes us back to a time when what transpired on that small Coronado base was largely unknown.

Naval Advising and Assistance: History, Challenges, and Analysis

Donald Stoker and Michael T. McMaster, eds. Solihull, West Midlands, UK: Helion and Company Press, 2017. 278 pp. Index, Biblio. $59.95.

Naval advising and assistance seems an under researched and poorly studied topic. Indeed, thorough studies with well-documented lessons and outcomes are scant. Given the exorbitant cost of a modern fleet, the United States relies more than ever on the naval capabilities of less-capable allies and partners, making this volume of historical research most welcome. The editors have assembled a body of arguably the best 12 essays on the subject. Five examine U.S. Navy advise and assist missions going back to the early 20th century. The scope is wide, covering everything from “adoption capacity theory” on the esoteric, academic end of the scale, to challenges, practical lessons, and useful vignettes from training the Republic of Vietnam Navy. The book is rich in detail and a valuable resource to both policy makers and operational practitioners currently embarked in one of the dozens of naval advise and assist missions around the world.

ν Captain Bray served as a naval intelligence officer for 28 years before retiring in 2016. Currently, he is a managing director in the Geopolitical Risk practice at Ankura.

On Grand Strategy

On Grand Strategy