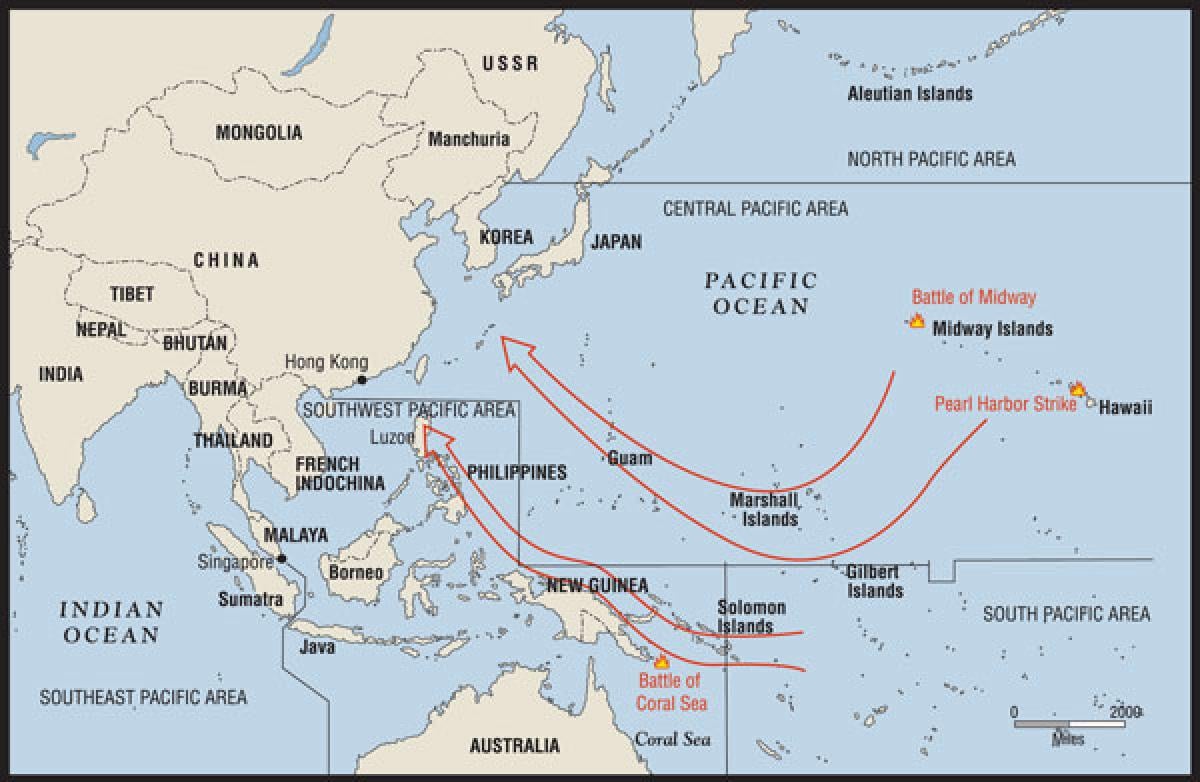

The gross ignorance or neglect of operational art has invariably had highly negative consequences, including the British misfortunes in Norway in 1940 and mainland Greece and Crete in 1941, the 1941–42 Allied losses in Southeast Asia, and the Japanese defeat in the Pacific war of 1941–45. The June 1942 Battle of Midway is perhaps the best example of the catastrophic consequences that a lack of operational thinking can have. The Japanese commander-in-chief of the Combined Fleet, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, headed a fleet twice the size of U.S. forces, yet due to a deeply flawed plan he suffered a decisive defeat that represented a turning point in the Pacific war.1 The main U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War (1965–73), aside from serious disconnects at the strategy and policy levels, was essentially conducted at the theater-strategic and tactical levels only; again, operational art was not applied.2 This also explains the Argentinian defeat in the Falklands/Malvinas conflict of 1982, and today, it is one reason that combating piracy off Somalia’s coast and in the Gulf of Aden has not been more successful.

Recent Service Efforts and Problems

Based on CNO guidance for 2009, the Navy organized Maritime Headquarters/Maritime Operations Centers with numbered fleets and naval component commanders. At the Naval War College, the Naval Operational Planning Course was established in 1998 and renamed in 2009 to the Maritime Advanced Warfighting School. The college established the Maritime Staff Operators Course in November 2007, and since 1994 its Joint Maritime Operations Department has had a solid program of teaching theory of joint operational warfare, as well as (since 2009) operational warfare at sea. Even so, the persistent problem is that too few future flag officers are sent to the college to take advantage of these courses.

The U.S. Army’s 1986 FM 100-5 Operations described operational art as the “employment of military forces to attain strategic goals in a theater of war or theater of operations through the design, organization, and conduct of campaigns and major operations.”3 Subsequently, that definition underwent several changes in service and joint doctrinal publications, resulting in a wordy, obfuscated explanation. The 2011 versions of JP 3-0 Joint Operations and JP 5-0 Joint Operations Planning define operational art as “the cognitive approach by commanders and staffs—supported by their skill, knowledge, experience, creativity, and judgment—to develop strategies, campaigns, and operations to organize and employ military forces by integrating ends, ways, and means.”4

A major error here is including “strategies” in operational art. Also, “ends, means, and ways” usually refer to strategy. Finally, there is no mention of strategic/operational objectives or the fact that operational art is concerned with planning, preparing, and conducting major operations and campaigns. In short, the U.S. military does not agree on what constitutes operational art.

Depending on the scale of the military objective, characteristics of the physical environment, and type of combat forces, the theory and practice of operational art may be similar or very different. Distinctions can be made according to whether it is practiced by multiservice/multinational or joint/combined forces, or whether it is conducted predominantly by a single service. Operational art may be executed on the ground or in the air, or it may be naval, or it may include components of all of those. Joint operational art is primarily concerned with the study and practice of campaigns, while each service is responsible for developing its own theory and practice.

A Bridge and an Interface

In naval terms, operational art links maritime strategy and naval tactics. The results of naval tactical actions are useful only when connected to a larger framework determined by policy and strategy and orchestrated by operational art. Better technology and/or numerical superiority in themselves are often insufficient for success in war. Operational art enables a smaller, better trained, and skillfully led force guided by sound strategy to defeat quickly and decisively a much larger but poorly trained and led enemy force. For the U.S. Navy, this art will be even more critical in the years ahead because of pending budgetary cuts that may lead to even more reduction in battle-force levels.

By thinking operationally, the Navy will considerably enhance its ability to conduct decisive warfare at sea in the event of a regional high-intensity conventional war. It will also greatly improve effectiveness in preparing for and conducting operations short of war, such as combating maritime terrorism and piracy, providing humanitarian assistance and disaster relief, and providing support to insurgency/counterinsurgency and peace operations.

Operational art ensures that the focus of combat forces is on the objectives, not on the effects or targets to be destroyed. The objective determines, among other things, the methods of combat forces’ employment, levels of war and command, scale of deployment and maneuver, center of gravity, deception, and so on.

The framework within which tactical actions are conducted is determined by operational art. Without that context, war at sea consists of a series of randomly fought major and minor naval tactical actions, with relative attrition as the only measure of success or failure. A series of victories may ultimately result in an operational or even strategic success, but over a longer time and with more losses to friendly forces than if these actions had been an integral part of a major naval or joint operation or campaign.

This art also provides the main input for writing service and joint/combined doctrine. It considerably reinforces the need for the closest cooperation between naval combat arms and joint forces. It is especially critical for the successful conduct of littoral warfare, such as may someday occur in the Persian Gulf, Taiwan Strait, or Korean Peninsula. True asymmetric warfare at sea makes full use of Air Force and Army capabilities to complement those of naval forces in their struggle for sea control or denial. The Air Force can secure, maintain, or deny sea control by destroying the enemy fleet at sea and its bases. It can strike coastal facilities and installations, conduct offensive mining, carry out maritime reconnaissance and surveillance, and attack or defend maritime trade, especially in littoral waters. Likewise, the Army might in some cases assist the Navy in securing or denying sea control by seizing and/or defending a strait, narrows, or important part or the coast.

Create an Operational Picture

The theory of operational art is developed using scientific methods, while its practical application is an art. The conduct of war is, thus, an art that depends on the skills, creativity, judgment, and wisdom of commanders and their staffs. The human element is the single-most important aspect of successfully conducting war at sea.

One of the principal requirements for command at the operational and strategic levels is to have a broad vision.5 The Germans aptly call this “operational thinking,” and it is not normally an inherent personality trait. Rather, it is acquired through education and training in peacetime. It ensures that combat forces contribute directly or indirectly to the accomplishment of the ultimate objective. Perhaps the most critical element of operational thinking is the commander’s operational perspective—the ability to see clearly and objectively all military and nonmilitary aspects of the situation in a given maritime theater.

Maritime operational commanders should have an uncanny ability to reduce complexities of the situation to their essentials. While avoiding seeing events and actions in isolation from one other, they should be able to connect disparate events and actions to create an operational picture of the situation. As in a chess game, a maritime operational commander must have the ability to envision the end state after the objective of a major operation or campaign is accomplished. He must correctly anticipate the enemy’s reaction to his actions, and then properly counteract until the end state is achieved.

Do Not Micromanage

By maintaining an operational perspective, the commander delegates authority to his tactical commanders, thereby ensuring them sufficient freedom to act. The main tool for providing them a framework within which to do this is to issue the commander’s intent. From there, subordinate tactical commanders can take the initiative while the maritime operational commander does everything possible to reduce the enemy’s freedom to act.6

In the years preceding U.S. involvement in World War II, there was an incresing tendency to interfere with the responsbilities of subordinate commanders. Admiral Ernest J. King, in one of his first actions after being appointed commander-in-chief of the Atlantic Fleet in February 1941, sent a circular criticizing the propensity of many flag officers to issue orders to subordinates telling them not only what to do, but how to do it. King considered that style to be the antithesis of the essence of command, directing that “it was essential to extend the knowledge and the practice of ‘initiative of the subordinates’ principle and in application until they are universal in the exercise of command throughout all the echelons of command.” Hence, orders and instructions should be framed in a way that allows for personal resourcefulness.7

Admirals King, Chester W. Nimitz, and Raymond A. Spruance were well known for giving brief, clear orders and letting subordinates exercise the intiative. King, as commander-in-chief, U.S. Navy, and Chief of Naval Operations, was tough and often harsh in dealing with subordinates, yet he reportedly did not interfere in the responsibilities of flag officers under him. King also disciplined himself not to press his combat commanders for information while an operation was in progress.8

Likewise, Nimitz, commander-in-chief, Pacific Ocean Area, commander-in-chief, Pacific Fleet, and commander, Central Pacific Ocean Area, usually stated what he wanted accomplished and why, giving certain timelines and a broad idea of what the operation would consist of. However, he generally allowed the fleet commanders or operational commanders at sea full freedom of action as to how to accomplish their assigned objective.9

Commanders who think operationally have a rare ability to properly balance space, time, and force versus operational or strategic objectives. They can properly evaluate the impact of information on each of these operational factors. They need to fully understand the influence of the physical environment on the employment of several combat arms or branches of a service, or of more than one service, as opposed to using single platforms, weapons, or combat arms. In other words, geographically they must grasp the operational versus tactical features. They should know and understand the interactions between strategy, operational art, tactics, and the levels of war. And they should appreciate the operational, as opposed to tactical, impact of technological advances.

A major problem in many navies, including that of the United States, is the firmly held belief that all a commander really needs is practical experience and intuition. Despite abundant evidence to the contrary, a deeply ingrained anti-intellectualism is responsible for erroneous views that a successful commander cannot be both a thinker and practitioner of naval warfare. Yet the most effective flag officers in U.S. naval history have been both intellectuals and sailors, as demonstrated by the careers of King, Nimitz, and Spruance.

Learn to Think Operationally

Operational thinking is only in rare cases the result of a commander’s inherent predisposition to think broadly and far ahead of current events. Most future maritime operational commanders and staff members have to develop this type of thought process by exerting sustained and systematic efforts over much of their professional careers. It is simply wrong to believe that operational thinking can evolve after a flag officer is assigned to that level of command.

Instead, mental work such as this results from the dynamic interplay of nonmilitary and military influences. Broader political, societal, and cultural conditions shape the country’s armed forces, and hence also military professional education and training. The military as an institution forms the environment within which an operational commander exercises his authority and responsibilities. Thus, the commander’s approach is a product of the national way of warfare as a whole, and the common operational outlook of the armed forces or a particular service.

This type of thinking is acquired through both direct and indirect influences. Obviously, war is the best opportunity for broadening the perspective and application of operational art. But opportunities to acquire such direct experience are relatively few, because major conflicts are rare. Hence, it is necessary to acquire such experience in peacetime, through participation in large-scale naval exercises and maneuvers, and planning and war games.

For example, in 1927 the Naval War College began for the first time the study of “operational” problems, in addition to the “strategical” and “tactical” ones it already addressed. In the 1930s, the Navy also repeatedly tested plans for operational employment of Fleet forces in a hypothetical war with Japan, via war games held at the Naval War College. In the interwar years, the college’s instructors and students examined strategy to be used in the event of a war with Japan. They endlessly debated which routes to be taken across the Pacific. The future Admiral King attended the senior course in 1932 and apparently learned his lessons well.10

Indirect influences include the study of military and naval history, foreign policy, diplomacy, geopolitics, international economics and finance, ethnicity, religions, and other issues that shape the situation in a given theater. Future maritime operational commanders and planners need to have thorough knowledge of the theater in which their forces are or will be employed. They should understand and appreciate other countries’ history, society, and culture. In fact, these indirect influences are more valuable and enduring because they are products of human experience. Life is too short and practical experience in combat too limited to acquire the necessary operational perspective; therefore, the greatest value of indirect experience lies in its greater variety and extent.11 Through a future commander’s professional education at service and joint colleges, these types of influences affect his or her ability to think in operational terms and to continue with self-education over the course of an entire career.

Base Improvisation on Solid Theory

Theoretical knowledge and understanding of a given aspect of naval warfare makes improvisation much easier in combat. Neglecting or ignoring naval theory invariably results in time lost and, more important, unnecessary losses in personnel and materiel. But theory cannot be properly developed without learning military and naval history, the greatest and most important source of indirect experience.

The U.S. Navy needs to rethink whether its neglect—even ignorance—of operational art might eventually lead to fateful consequences, as happened to the Imperial Japanese Navy in the Pacific war. The United States has not fought a serious competitor at sea since then. The Navy has participated in several regional wars, but in none of them did it face a momentous naval challenger.

Hence, the service’s overemphasis on tactics and technology has not—so far—resulted in any major losses. The Navy has enjoyed numerical superiority over any would-be opponent at sea. This is going to change in the future. The People’s Liberation Army Navy will emerge as a peer competitor to the U.S. Navy in the western Pacific and probably beyond. And the Chinese pay great attention to operational art.

The Navy’s challenge is not only to strengthen the U.S. deterrent posture but also to obtain and maintain sea control in any potential war with a major competitor. This task will not be easy, because numerically the U.S. battle force is much smaller than in the early 1990s. It is debatable whether the reduction in numbers led to the desired increase in the battle force’s combat potential. But the smaller the force, the greater the need to fight decisively, to embrace and master operational art. Otherwise, the Navy will not perform well when facing a skillful and determined opponent who thinks and acts operationally.

1. Carl L. Boyd, review of Pat Frank and Joseph D. Harrington, Rendez-vous at Midway: USS Yorktown and the Japanese Carrier Fleet, in Military Affairs 31, no. 3 (autumn 1967), p. 156.

2. Edward N. Lutwak, “The Operational Level of War,” International Security (winter 1980–81), p. 62.

3. Headquarters, Department of the Army, FM 100-5: Operations (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, May 1986), p. 10.

4. JP 3-0 Joint Operations (11 August 2011), p. GL-14; JP 5-0 Joint Operational Planning (11 August 2011), p. GL-13.

5. David Jablonsky, “Strategy and the Operational Level of War,” part 1 Parameters (spring 1987), p. 71.

6. Fuehrungsakademie der Bundeswehr, Arbeitspapier (working paper), Operative Fuehrung (Hamburg, Fuehrungsakademie der Bundeswehr 1992), p. 18.

7. David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy 1897–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), p. 512.

8. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), p. 193.

9. Richard P. Harrison, Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz: The Right Man for the Times (Toronto: Canadian Forces College, Advanced Military Studies Course 2, December 1999), p. 7; Thomas B. Buell, The Quiet Warrior: A Biography of Admiral Raymond A. Spruance (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1988), p. 173.

10. Thomas B. Buell, Master of Sea Power: A Biography of Fleet Admiral Ernest J. King (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1980), p. xxv.

11. B. H. Liddell Hart, Strategy (New York: F. A. Praeger, 1954), pp. 23–24.