Shortly after the August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin episode that drew the United States deeper into the Vietnam War, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara sent two civilian officials to the U.S. Naval Base at Subic Bay, Philippines, to conduct an inquiry into what happened. As the Chief of Staff for the Commander of the U.S. Seventh Fleet, I had been sent to sit in on the inquiry. I heard one eyewitness, an experienced petty officer, asked whether he could have mistaken the trail of a dolphin for the wake of a torpedo. He replied with some heat, "Sir, I have been a destroyerman for 15 years and I know the [expletive deleted] difference between a dolphin and a torpedo wake. That was a [expletive deleted] torpedo."

All operational commanders involved in the Tonkin episode-from the captains of the two ships and their task force commander, Captain John J. Herrick, to the higher-ranking operational commanders including Vice Admiral Roy Johnson, Commander of the Seventh Fleet in the Western Pacific; Admiral Thomas Moorer, Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet; and Admiral Ulysses S. Grant Sharpe, Commander in Chief, Pacific-were convinced attacks had taken place on 4 August but only after they and their staffs had thoroughly assessed all available evidence. In Washington, however, confusion arose suggesting that whoever briefed the national leaders failed to place in clear perspective or even consider the value of the professional testimonies and evaluations sent to the capital.

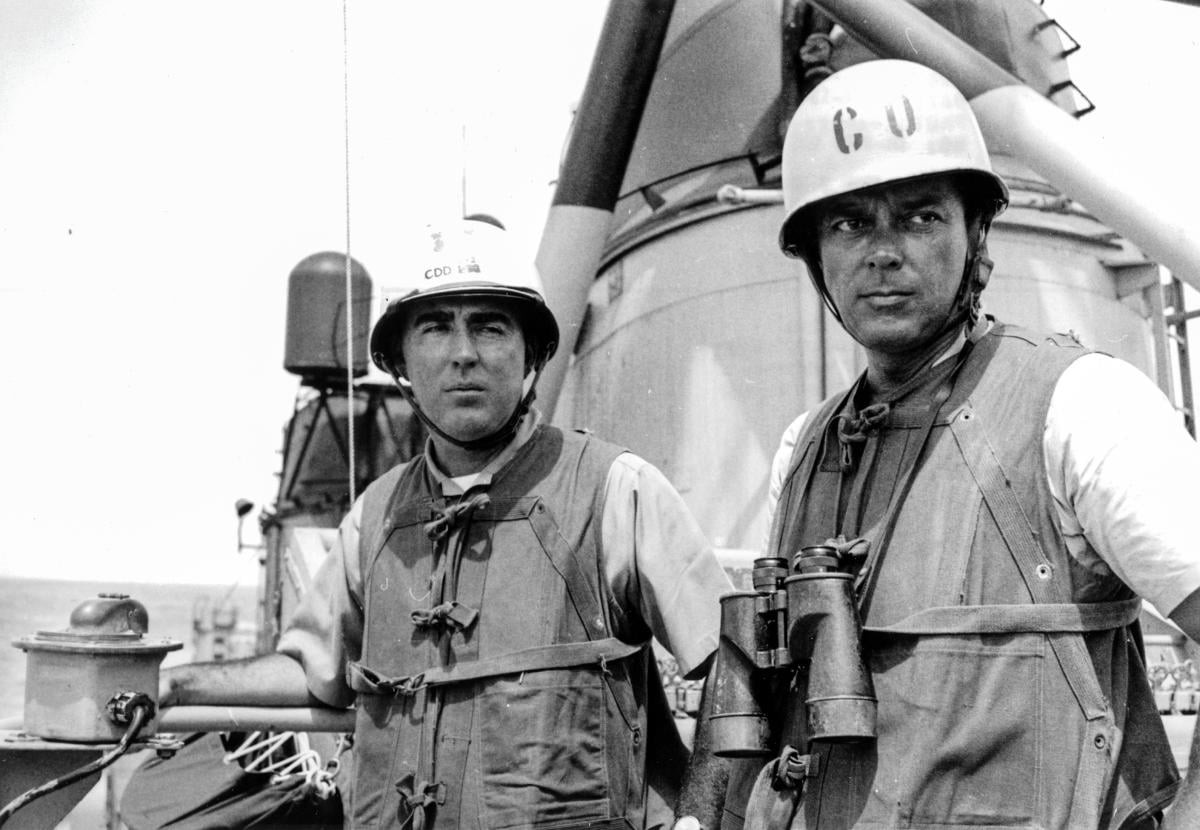

Two American destroyers, the USS Maddox (DD-731) and Turner Joy (DD-951), patrolling in international waters off the coast of North Vietnam the night of 4 August, had reported being attacked by North Vietnamese torpedo boats. The incident followed a bold daylight attack by torpedo boats against the Maddox two days earlier, during which two of the hostile boats were sunk by the destroyer and U.S. carrier aircraft. The subsequent actions of 4 August occurred on a dark, moonless, overcast night; there was some uncertainty as to details. A flurry of messages from higher commands and Washington wanted immediate details. Within hours Captain Herrick, after evaluations with the captains of the two ships, reported on the 4 August action: "Certain that original ambush was bonafide. Details of action following present a confusing picture. Have interviewed witnesses who made positive visual sightings. . . ."1

Compelling Eyewitness Evidence

A torpedo wake was sighted passing abeam of the Turner Joy from aft to forward on the same bearing as one reported by radio from the Maddox just moments before. This sighting was made by at least four of the Turner Joy's topside Sailors: the forward gun director officer, Lieutenant (junior grade) John J. Barry; Seaman Larry O. Litton, also in the gun director; the port lookout Seaman Edwin R. Sentel; and Seaman Roger N. Bergland, operating the aft gun directorr.

One radar target (presumably a torpedo boat) was taken under fire by the Turner Joy. It was hit many times and disappeared from all radars. The commanding officer of the Turner Joy, Commander Robert C. Barnhart Jr., observed a thick column of black smoke from the target, as did other Sailors.

Later during the attack, a searchlight (possibly from a larger North Vietnamese Swatow-class boat vectoring the torpedo boats from a distance) was observed by all signal-bridge and maneuvering-bridge personnel, including Commander Barnhart. The beam of the searchlight was seen to swing in an arc toward the Turner Joy but was immediately extinguished when aircraft from the combat air patrol flying overhead approached the vicinity of the searchlight. Chief Quartermaster Walter L. Shishim, Signalman Richard B. Johnson, Quartermaster Richard D. Nooks, Signalman Richard M Basino, and Signalman Gary D. Carroll, stationed on the Turner Joy's signal bridge, all made written statements that they had sighted the searchlight.

The silhouette of an attacking boat was seen by at least four Turner Joy Sailors when the boat came between the flares dropped by an aircraft and the ship. When these four men-Boatswain's Mate Donald V. Sharkey, Seaman Kenneth E. Garrison, Gunner's Mate Delmer Jones, and Fire Control Technician Arthur B. Anderson-were asked to sketch what they had seen, they accurately sketched North Vietnamese P-4-type boats. None of the four had ever seen a picture of a P-4 boat before. In addition, Gunner's Mate Jose San Augustin, stationed aft of the signal bridge on the Maddox, saw the outline of a boat silhouetted by the light of a burst from a 3-inch projectile fired at it.

Two Marines-Sergeant Mathew B. Allasre and Lance Corporal David A. Prouty-manning machine guns on the Maddox saw lights go up the port side of the ship, go out ahead, and pass down the starboard side. Their written statement attests to their belief that the lights came from one or more small boats moving at high speed.

Commander G. H. Edmondson, commanding officer of Attack Squadron 52 from the carrier USS Ticonderoga (CVA-14), and his wingman, Lieutenant J. A. Burton, were flying at altitudes of between 700 and 1,500 feet in the vicinity of the two destroyers at the time of the torpedo attack, when both men sighted gun flashes on the surface of the water as well as light anti-aircraft bursts at their approximate altitude. On one pass over the destroyers, both pilots positively sighted a "snakey" high-speed wake (a torpedo-boat signature) 1.5 miles ahead of the lead destroyer Maddox.

Sadly, in subsequent critiques on Tonkin, scant if any credibility has been given to these Sailors and officers who provided such compelling evidence of the attacks of 4 August. As with eyewitnesses anywhere, one or two or even three could have been in error in parts of what they saw-but not all of them on everything. These were highly trained, experienced, and competent Sailors, reporting directly in their areas of expertise and duty.

Lead-in to Tonkin

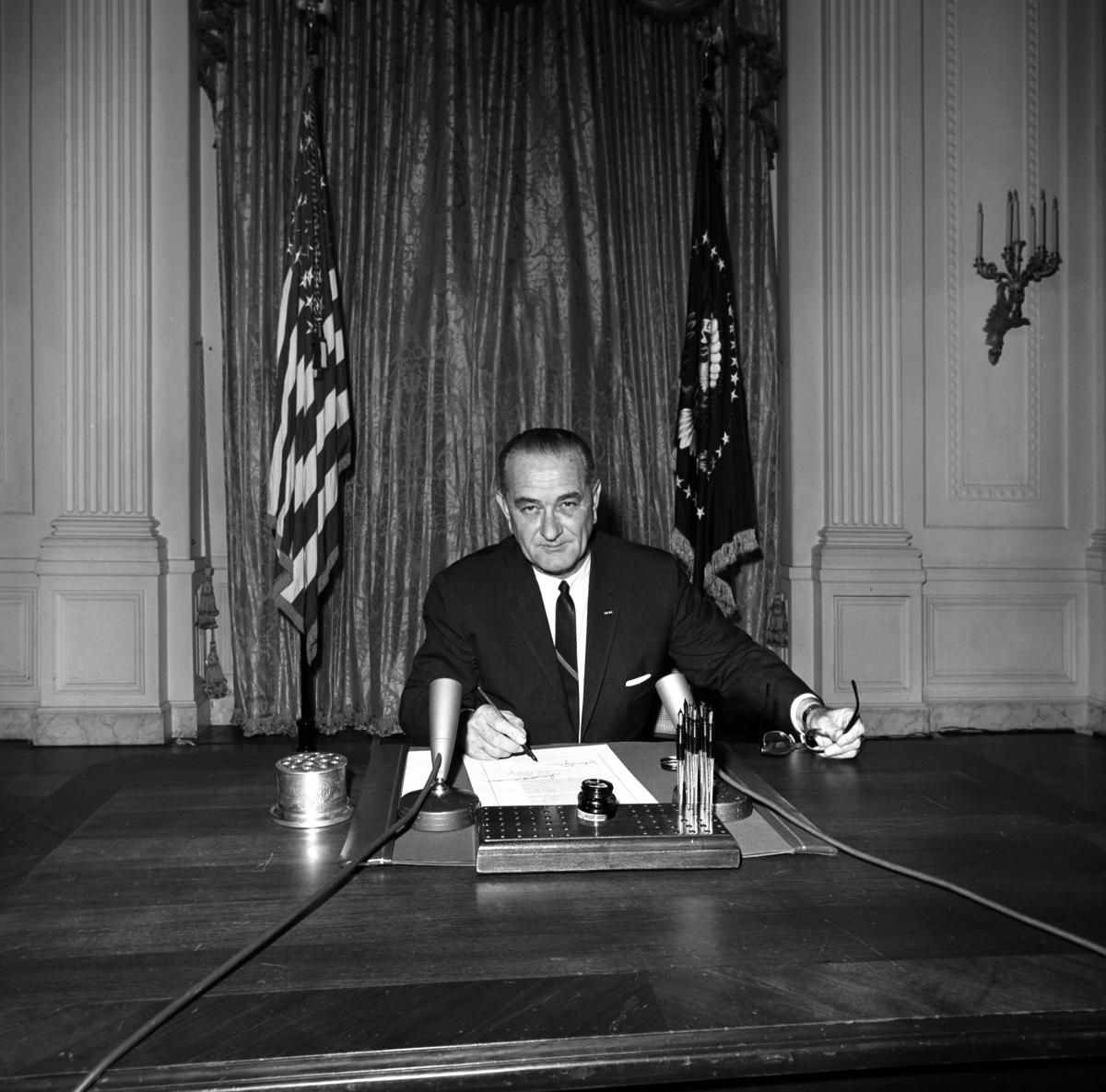

A brief review of developments prior to the attacks of 4 August is relevant to understanding the role of U.S warships in the Gulf of Tonkin. The United States was strongly committed to preventing a communist takeover of South Vietnam; the policy had evolved under Presidents Truman, Eisenhower, Kennedy, and Johnson, with strong congressional support. In May l959 the Communist Politburo of North Vietnam made a decision to "liberate" South Vietnam through the infiltration of guerrilla fighters and supplies, and through political subversion via agents of influence.2 By 1961, security in South Vietnam had deteriorated to such an extent that President Kennedy approved a substantial increase in the U.S. military-advisory program to 17,500 American servicemen, and later authorized U.S. helicopters to fire at the enemy. When President Johnson took office in November 1963, many U.S. military advisers in Vietnam were actively engaged in combat alongside the South Vietnamese.

In 1962 periodic intelligence patrols, later called Desoto patrols, were commenced by ships of the U.S. Seventh Fleet in international waters off the coast of North Vietnam to collect radio and radar signals emanating primarily from shore-based stations. Similar patrols on the periphery of the Soviet Union, China, and North Korea were already in progress.

In January 1964 the U.S. National Security Council approved Central Intelligence Agency support for South Vietnamese covert operations against North Vietnam. OpPlan 34A, as it was code-named, was composed of two types of operations. In one, boats and aircraft dropped South Vietnamese agents equipped with radios into North Vietnam to conduct sabotage and to gather intelligence; in the other, high-speed patrol boats manned by South Vietnamese or foreign mercenary crews launched hit-and-run attacks against North Vietnamese shore and island installations.3 The Seventh Fleet was not involved with either operation.

On 31 July 1964, the Maddox commenced a Desoto patrol while under orders to avoid provocative actions and remain in international waters. The purpose was to obtain information by visual and electronic means, and specifically to observe any North Vietnamese naval activities in these waters in view of evidence of infiltration by sea of North Vietnamese armed personnel and equipment into South Vietnam.

On 2 August, while the Maddox was 28 miles from the coast of North Vietnam and heading away, she was attacked in daylight by three North Vietnamese torpedo boats. The commanding officer, Commander Herbert L. Ogier, had sent a flash message reporting that three torpedo boats were closing rapidly at high speed, apparently to attack the Maddox, and he intended to open fire in his own defense. A second message from the destroyer reported at least three torpedoes and machine-gun fire being directed at the ship. The Maddox avoided the torpedoes and, together with aircraft from the Ticonderoga, sank or damaged the attacking torpedo boats.

Within days of the attack, critics claimed that the patrol was "provocative to North Vietnam" because it was conducted in support of an ongoing South Vietnamese OpPlan 34A raid. This accusation was inaccurate. When the South Vietnamese conducted the first of their two OpPlan 34A naval operations against North Vietnamese targets during this period, the Maddox patrol had not even begun, and the ship was at least 130 miles to the southeast. The 2 August attack on the Maddox took place 63 hours after completion of South Vietnam's naval operation. On 4 August, when South Vietnamese boats conducted their second foray against the North, the Maddox and Turner Joy were at least 70 nautical miles to the northeast.4

Moreover, the suggestion that a lone destroyer conducting a passive mission in international waters well away from the North Vietnamese coast was "provocative" lacked credibility. Had the United States intended to be provocative, an aircraft carrier would have provided a more demonstrative show of force. As it was, the Ticonderoga had been directed to operate well to seaward of the Maddox to avoid such inference. As recommended by the Pacific Fleet commander, the President authorized the Desoto patrol to continue, with the Maddox accompanied by the Turner Joy.5 The aircraft carrier USS Constellation (CVA-64), then in Hong Kong, was directed to sail toward the Gulf of Tonkin.

On the evening of 4 August (Tonkin Gulf time), "an intelligence report of a highly classified and unimpeachable nature [was] received shortly before the engagement, that North Vietnamese naval forces intended to attack the Maddox and Turner Joy," according to later Senate hearings.6 While the Maddox and Turner Joy were on patrol approximately 60 miles from the North Vietnamese coast, Captain Herrick, the task force commander, saw on radar at least five contacts he evaluated as probable torpedo boats about 36 miles to the northeast. He ordered both ships to increase speed and change course to the southeast to avoid what he thought was a trap.

About an hour later the two destroyers held radar contacts approximately 14 miles to the east on courses and speeds indicating rapid closure on both of them. Soon, the Maddox reported that the ship patrol was being approached by high-speed contacts and that an attack appeared imminent.

Escalating Situation, Confusing Details

Amplifying messages quickly followed. A message from Captain Herrick reported the two destroyers, then situated 60-65 miles from the coast of North Vietnam, were under attack. At the same time special intelligence sources reported that the North Vietnamese vessels stated they had our ships under attack.7

A flurry of messages followed with supporting details. Some were ambiguous, some conflicting, and many responded to urgent questions from up the chain of command and from Washington. It was a confusing picture at first, but not unexpected to those battle-tested in World War II. One of Captain Herrick's early messages reported that the two ships were under "continuous torpedo attack." After further evaluation, he reported: "Review of action makes many reported contacts and torpedoes fired appear doubtful" and suggested "complete evaluation before any further action taken."

Captain Herrick and Commander Ogier of the Maddox suspected that most of the Maddox's 26 sonar reports were in error and conducted an evaluation confirming their suspicions. Both destroyers had been weaving at high speeds, and as Herrick explained later, "It was the echo of our outgoing sonar beam hitting the rudders which were then full over and reflected back into the receiver." Constant high-speed weaving of the two ships could also result in multiple sightings of the same torpedo wake.

After further evaluation with both destroyer skippers, Herrick sent a clarifying message to higher commands and Washington:

Certain that original ambush was bonafide. Details of action following present a confusing picture. Have interviewed witnesses who made positive visual sightings of cockpit lights or similar passing near Maddox. Several reported torpedoes were probably boats themselves which were observed to make several close passes on Maddox. Own ship's screw noises or rudders may have accounted for some. At present cannot even estimate the number of boats involved. Turner Joy reports two torpedoes passed near her.8

Many critics have made much of Captain Herrick's earlier message that expressed doubt. They ignore or downplay the importance of his final message in which he asserts that his doubt was only of the validity of some contacts, not about the fact of an attack. At hearings by the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in 1968, Captain Herrick testified he had no doubt that an attack had occurred.9 In media interviews reported in The New York Times, Captain Herrick confirmed his comment that there could be "no doubt" that his ships were attacked and denied that the attacks were provoked.10

As the Seventh Fleet flagship USS Oklahoma City (CLG-5) was approaching Tonkin Gulf, Vice Admiral Roy Johnson ordered Commander Andy Kerr, our staff legal officer who was also a qualified submarine officer, "to go aboard those two ships and compare all of their logs and plots," and bring the track charts back to the flagship. Commander Kerr later recalled:

I was lowered by the Oklahoma City's helicopter to the deck of the Maddox. On our way we had picked up the Operations Officer of the Turner Joy. He had with him all of that ship's data. We carefully constructed a composite chart. It reflected all of the information available on both ships, during the incident. The tracks of both ships were plotted. All radar, sonar, and visual data, with times, ranges and bearings were entered. The chart showed remarkable correlation. False contacts are usually random and do not persist for long periods. The same false contacts would seldom be sensed by two ships that were in different positions. There was great consistency between all of the contacts made by both ships. Furthermore, the tracks of the attacking vessels, as plotted independently by both the Maddox and Turner Joy, coincided and were precisely what one would expect from attacking torpedo boats. Lastly, the plotted speed of the contacts was comparable to the speed of the North Vietnamese torpedo boats that had attacked the Maddox in daylight two days before.

After returning to the Oklahoma City, Commander Kerr shared his findings:

On Admiral Johnson's staff, the chart was analyzed by the Chief of Staff, Captain Lloyd ("Joe") Vasey [the author of this article] and the staff operations section. They then reviewed it with the admiral. All reached the same conclusion: The composite track chart left no doubt whatsoever. An attack had taken place. Admiral Johnson dispatched that information to the Commander of the U.S. Pacific Fleet, Admiral Thomas Moorer, with headquarters at Pearl Harbor. The chart was then flown back to Moorer's headquarters.11

It was during this period that Secretary of Defense McNamara sent the two aformentioned senior officials to Subic Bay to interview key witnesses from the destroyers. In a message to Admiral Johnson, Admiral Moorer requested that I be sent to sit in on the inquiry as an observer.

One senior Department of Defense official was the legal counsel for the Secretary of Defense. He conducted his inquiry in an informal, straightforward, polite question-and-answer session that lasted several hours. The Sailors and young officers were impressive and convincing. They provided verbal confirmation to support the official reports of the 4 August action made by Captain Herrick and the destroyers' commanding officers. When the session was over, the senior DOD official asked me to read his report. It concluded that attacks against our destroyers the night of August 4 had occurred, although the details would require further data refinement.

In testimony to the Senate Committee on Foreign Relations in 1968, Secretary of Defense-McNamara said:

In July of 1967 we captured an individual of some rank in the North Vietnamese Navy who gave us the name of the squadron commander in charge of PT boats participating in the August 2 attack, and it is that name that we had reported to us (via special intelligence sources) as having participated in the August 4 attack at the time of the attack, and it is his boat by number that we had reported to us as having participated in the August 4 attack at the time of the attack.12

The Incident's Afterlife

Over the past several years, the Gulf of Tonkin has again commanded the attention of scholars and the media with the declassification by the National Security Agency of more than 140 top-secret documents-histories, chronologies, signals intelligence (SIGINT) reports, and oral history interviews. Included is a controversial article by NSA historian Robert Hanyok, "Skunks, Bogies, Silent Hounds, and the Flying Fish: The Gulf of Tonkin Mystery, 2-4 August 1964," which seeks to confirm what other historians have long argued, "the received wisdom" that there was no second attack on U.S. ships in Tonkin by North Vietnamese torpedo boats.13

I have reviewed most of the released material in writing this article and wish to commend Hanyok for his analysis of a complicated maze of SIGINT information. Hanyok's treatise is now viewed by many historians as the accepted assessment of the events of August 1964.

But there are serious flaws in Hanyok's analysis that undermine its credibility.

First, while he presents convincing arguments from a SIGINT perspective that there was no evidence of North Vietnamese torpedo boat attacks on 4 August, he also comments, "It seems that the NSA position (presented to President Johnson) was a fairly straightforward one: that the second attack occurred [emphasis added]." Then, he implies a political motive behind the NSA position: "This allowed President Johnson to shift the blame for the final decision (to order an air attack against North Vietnam) from himself to the 'experts' who had assured him of the strength of the evidence from the SIGINT."14 But Hanyok presents no proof to support this allegation.

Sadly, most critiques over the years have relied on such studies leading to claims or implications that our nation's civilian and military leaders knew or suspected there had been no attack, and nevertheless ordered and conducted the reprisal air strikes against North Vietnam.

Where the assertions of Hanyok and other critics self-destruct is (1) their dismissal of the human testimony of competent witnesses cited earlier, and (2) the "unimpeachable" special intelligence Secretary McNamara cited. Instead, the arguments rest on Hanyok's analysis of SIGINT evidence. In his words, "Without the signals intelligence information, the administration had only the confused and conflicting testimony and evidence of the men and equipment involved in the incident."15

In early 1965, with the commitment of major U.S. ground forces to the Vietnam struggle and the start of a sustained bombing campaign against selected targets in North Vietnam, American casualties mounted as did public and congressional opposition to the war. From then on, the perceived wisdom about the Tonkin Gulf actions and the Vietnam War was cast in iron, deceiving Americans for generations to come.

1. Personal statements of 4 August action, Selected Naval Documents, Vietnam, Naval Historical Center (NHC). CincPacFlt msg. 071101Z August 1964 and enclosures, “Proof of Attack,” cited from NHC, message from Admiral Thomas Moorer, then Commander, U.S. Pacific Fleet.

2. Professor Robert Tuner, communication to the author, based on Tuner’s personal experience while serving in JUSPAO, a branch of the American Embassy at Saigon; and on his book Vietnamese Communism: Its Origin and Development (Palo Alto: Hoover Institution, 1975).

3. Robert S. McNamara, In Retrospect: The Tragedy and Lessons of Vietnam (New York: Random House, 1995), pp.103, 129.

4. Hearings before the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, 20 February 1968 (Washington, D.C.: U.S.Government Printing Office), p. 9.

5. Ibid., p. 10.

6. Ibid., p. 18.

7. Ibid., pp. 10–11.

8. Congressional Research Service, The U.S. Government and the Vietnam War: Part II, 1961–64, (prepared for the Committee on Foreign Relations, U.S. Senate, December 1984), p. 292.

9. Andy Kerr, A Journey Amongst the Good and the Great (Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1987), p. 205.

10. “Captain Confirms Attack in Tonkin,” The New York Times, 24 February 1968.

11. Kerr, p. 178.

12. Statement of Secretary of Defense McNamara, 20 February 1968, Hearings, p. 75.

13. Robert J. Hanyok, “Skunks, Bogies, Silent Hounds, and the Flying Fish: The Gulf of Tonkin Mystery, 2–4 August 1964” (National Security Archive, declassified 2005), available at www.nsa.gov/public_info/_files/gulf_of_tonkin/articles/rel1_skunks_bogies.pdf.

14. Ibid.

15. Ibid.