The United States has flourished because of the natural geographic barriers bestowed on it by the Atlantic and Pacific Oceans. By 1945, the U.S. military reigned supreme worldwide. By 1991, the demise of the Soviet Union and of communism had solidified U.S. political and economic dominance. Lulled thereafter into a false sense of protracted national security, the American people and their government focused inward, oblivious to international realities. An arrogant and disconnected unipolar United States emerged. Our myopic leaders routinely ignored omnipresent geopolitical forces.

Horrifically, on 11 September 2001, our natural geographic advantages were no more.1 The United States became strategically weak almost overnight. The convoluted realm of Islamic geopolitics annihilated our geographic security. Old political alliances and international law cannot diminish such ominous geographic and demographic realities. Resolute and innovative military force is a must.

Irrefutably, the U.S. Navy is the preeminent sea power of all time. Global U.S. military dominance is uncontested today in large part because of our omnipresent naval might. The U.S. Navy is a first-class blue-water arsenal with supremacy over the air, surface, subsurface, and electromagnetic spectrum. The power of U.S. naval aviation, its surface and subsurface prowess, and expeditionary strike group domination cannot be duplicated by any nation or even alliance of nations. Most important, U.S. naval doctrine, strategy, and tactics have been validated in battle for more than 200 years. Given all this, the U.S. Navy’s domination is absolute for the foreseeable future.

The United States is a maritime nation. Unfortunately, our future adversaries are all continental. So now what?

“Sea Power 21” is the U.S. Navy’s vision of the future, a supposed transformation expanding maritime strength in the joint arena. It is built on three central tenets: Sea Strike, Sea Shield, and Sea Basing. Such strategic thinking is consistent with Alfred Thayer Mahan’s dictum—“certain principles of naval strategy remain constant; nations ignore them at their own peril”—but it is hardly transformational, innovative, or overtly joint. It appears to be more of the same, with an end state of 375 ships whose main focus is the continuation of blue-water domination built around traditional carrier battle groups.

As currently articulated, “Sea Power 21” is an untimely and frivolous drain on limited U.S. defense resources because it is centered on the obsolete containment stratagem of the Cold War. Perpetual containment of Eurasia or the Middle East, or anywhere else for that matter, no longer is in U.S. national interest. Continued blue-water domination, at the detriment of littoral warfare capabilities, does not enhance future joint war fighting or significantly contribute to U.S. victory over terrorism. Such a risk-averse naval strategy will not aid in the defeat of Islamist fanatics today, tomorrow, or ten years hence. Foremost, the “Sea Power 21” ideologues demonstrate strategic contempt for our Islamic adversaries’ method of warfare.

Historically, navies have fought as concentrated forces against similarly centralized foes in set battles at sea. The global war on terrorism is decentralized by nature—and ashore. There will be no blue-water engagements. Instead, brown-water engagements will include limited littoral security and patrolling, and logistical and riverine operations. Geographically constraining and confining waterways and urban battlefields are no place for large capital ships, much less carrier battle groups. Even the Navy’s revered intelligence-collection apparatus are nearly impotent given the low-tech clandestine nature and inland urban locale of our current enemies and their preferred area of operations. Further complicating the “Sea Power 21” vision, the Department of Defense is adopting a “lily-pad” expeditionary basing concept, which will require thousands of sailors and smaller vessels for security, logistical, and littoral support worldwide.

Conventional naval warfare, with its reliance on carrier battle groups, other large surface ships, and submarines, offers little combat power for joint commanders in the global war on terror. Ironically, the U.S. Coast Guard is better suited for many low-intensity littoral missions today than is the Navy. So what is the U.S. Navy’s role in a global, continental terrorist war waged primarily among ancient cities in the Middle East and Central Asian hinterlands?

Geopolitical Realities, Trends, and Issues

The realpolitik of the U.S. position two and a half years after 11 September is not merely national survival or economic enrichment. The Bush administration’s quest is much grander in scale than that. The U.S. grand strategy is to rid the world of catastrophic terrorism and to prevent it from mutating out of control. Diminishing the clash of cultures is the endgame.

This is an unprecedented strategy. It implies terminating egregious political oppression, in contrast to World War II and the Cold War’s egregious military oppression. Key to accomplishing this lofty objective is an international commitment to promote political self-determination at the expense of abusive dictators. Otherwise, the two billion people trapped in a downward spiraling economic genocide cannot and will not contribute to sustainable global peace and prosperity.

The fundamental tenets of the Heartland and the Rimland geopolitical theories (see Figure 1) are in dire need of modification now that the old bipolar Cold War calculations are obsolete. Yet, “Sea Power 21” strategists continue to embrace Nicholas Spykman’s Rimland theory: “Who controls the Rimland rules Eurasia; who rules Eurasia controls the destinies of the world.” While militarily valid, this is now a moot point politically. According to Sir Halford Mackinder, “Who rules Eastern Europe commands the Heartland; who rules the Heartland commands the World-Island; who rules the World Island commands the world.” The current unipolar geopolitical situation may be more advantageous than Mackinder or Spykman ever could have imagined, but these theories do not adequately address the end of the Cold War, the emergence of militant theocracy, expanding global economic interdependency, technological and telecommunications advances, or devastating ballistic missile and weapons of mass destruction threats against noncombatant populations.

The two-year-old counterinsurgency operation in Afghanistan is likely representative of future U.S. military operations over the next 10-20 years. Carrier-based air strikes and Tomahawk missile attacks (surface and subsurface) comprise the majority of the U.S. Navy’s combat contribution. Ashore, most of the SEALs are under the operational control of Special Operations Command and no longer are dedicated fleet assets, further limiting U.S. Navy combat contributions. Seabees routinely are attached to ground commanders. With this in mind, continued acquisition of and reliance on prohibitively expensive carriers, nuclear submarines, and the like, while amphibious warfighting capabilities dwindle and littoral penetration capabilities languish, cannot be considered combat essential or in the national interests by any measure. Sustained peacekeeping and civil affairs operations in far-flung countries will become more commonplace. Traditional naval warfighting prowess is ancillary at best.

DoD Realities

Maneuver warfare is DoD’s stated joint military doctrine. Its essential tenet is to force the enemy to fight on your terms—at your preferred time and place. Ironically, this is the same strategy employed by terrorists, insurgents, and guerrillas. Modern U.S. maneuver warfare also espouses attacking your enemy’s center of gravity. Economically and politically, our adversaries’ center of gravity is dispersed among 1.3 billion Muslims in 56 nations. Primarily, our focus is on the Middle East; secondarily, on Indonesia, with its massive gas reserves and vital sea-lanes. Our tertiary targets are Jihadist insurgencies within Thailand, the Philippines, Malaysia, and elsewhere. Militarily, the centers of gravity are less well defined and fluctuate as international police and combat operations impede our adversaries’ offensive combat capabilities. Corrupt governments are logical starting places. Otherwise, the best approach is to follow the money, and to infiltrate and destroy as appropriate—classic counterinsurgency warfare (not a Navy forte). U.S. political, economic, and military muscle must be used in concert with our allies if we hope to defeat the radical Islamists’ crusade.

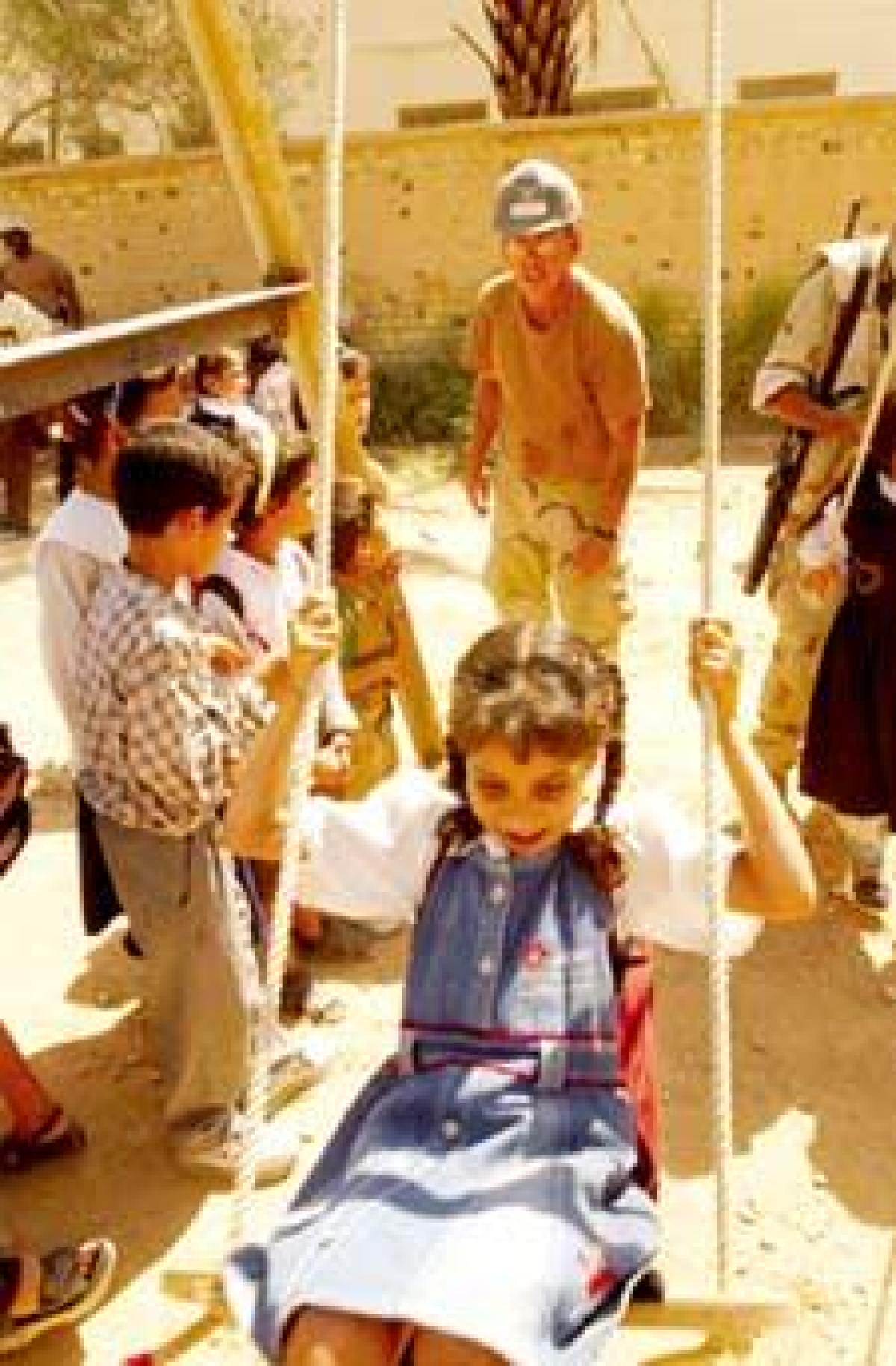

In this new environment, against this new enemy, counterinsurgency imperatives outweigh high-tech asymmetrical warfare fantasies. Therefore, tactical implementation of an improved combined action platoon (ICAP) operational strategy is the ideal means to achieve sustainable victory in a prolonged war in every clime and place. Modern ICAP innovations must include: strong command, control, communications, computers, intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (C4ISR) with “actionable” intelligence feeds; foreign area officers; regional air-land reaction forces for emergencies; no-fly zones; state-of-the-art communications; counterintelligence teams; interrogator/translator teams; regional civil affairs units; explosive ordnance disposal and engineer expertise; intensive and ongoing cultural skills/indigenous indoctrination; language training; and other such specialties. Additional support must include rotating regional units of Seabees, medical and dental providers, including female corpsmen to appease Islamic religious sensitivities, and even nongovernmental organizations that can rebuild, train, and create sustainable livelihoods among the villagers. Reasonable and staggered tour rotations (for units and individuals) will be paramount to the sustainability of this combat-tested pacification strategy. Police and intelligence collaboration are vital ingredients in support of ICAP, as are enthusiastic and properly trained, organized, and equipped indigenous forces. Renewed U.S. counterinsurgency expertise is the raison d’être of DoD now. Resurrect lessons learned from the Philippine Insurrection (1899-1902), the Banana Wars, and Vietnam. The Small Wars Manual is a fine starting point.

Future Combat Needs

The global war on terrorism is neither a strategic aviation nor a blue-water war. “Sea Power 21” advocates must accept this tactical reality and transform accordingly.

The Navy’s stated goal of 375 ships has negligible bearing on the destruction of terrorists. Our Islamist adversaries have adopted a continental strategy. They will not fight us at sea or in the air or on traditional naval terms. Terrorists and guerrillas by nature do not mass their forces, relying instead on deception, stealth, and economy of force ashore intermingled with innocent civilians. Symbolic soft targets, such as embassies and marketplaces, remain the Jihadists’ first choice. “Sea Power 21” does not alleviate these threats.

Global merchant fleets, massive containerships, and oil and gas transport behemoths remain vulnerable to terrorists, as do all major port and fueling facilities. Yet, these predictable maritime vulnerabilities generally fall under the realm of domestic security and are the domain of coast guards. A “Sea Power 21”-oriented Navy will offer little deterrence.

Secretary of Defense Donald Rumsfeld already has drawn a bead on the Army. Capital ships of a bygone era are reasonable next targets, as are prohibitively expensive piloted attack aircraft. The Littoral Combat Ship and the DD(X) concepts are steps in the right direction, if they can be delivered in a timely manner and quantity and doctrinally divorced from the carrier group fanatics. Likewise, the Sea Warrior personnel initiatives must access and train exponentially more naval intelligence professionals, UCAV operators, linguists, Seabees, female corpsmen, civil affairs personnel, logisticians, and maritime security specialists at the expense of submariners, surface warfare officers, aviators, and nuclear technicians.

The definitive failing of U.S. Navy shipbuilding is the chronic dearth of littoral, amphibious, and riverine vessels. Put bluntly, the preponderance of Navy assets, actual and proposed, cannot successfully detect, deter, or attack al Qaeda et al. “Sea Power 21” provides very little new combat power and remains constrained regarding the mounting Jihadist insurgencies in the Middle East. In Southeast Asia, thousands of islands provide sanctuary to terrorists and pirates. If the Indonesian conflagration escalates, it will require tremendous naval resources to win against the Jihadists (control and security of sea lines of communication, riverine operations and patrol craft raids, massive sealift for refugees). Maritime security for the Strait of Malacca and antipiracy operations will dominate allied Southeast Asian naval powers for decades to come. Carrier battle groups are impotent in this environment. The littoral dominion is the future.

Former Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Arleigh Burke was passionate about providing appropriate training and organizational innovation to sustain future combat needs. “Sea Power 21” advocates should heed that sage advice. Blue-water dominated containment is passé. Once again, small wars (e.g., Bosnia, Colombia, and Afghanistan) dominate U.S. strategic, operational, and tactical thought. Multiple, independent, and sustainable expeditionary ground offensives are the main focus of U.S. war fighting. The chief roles of the U.S. Navy for the next 10-20 years must be amphibious power projection, littoral force protection and expansion, and logistical sustainability. Qualified personnel—not merely 375 ships and more systems—must be the focal point of U.S. naval strategy and shipbuilding. People win wars, especially counterinsurgencies; machines cannot.6 At the end of the day, small units of infantrymen must hunt down strange people in foreign lands and kill them. Does the U.S. Navy’s “Sea Power 21” strategy help or hinder this endeavor? A global intifada is upon us—the barbarians are at the gates.

Paul Marx enlisted in the Marine Corps at 17. He earned a bachelor’s in Russian-Soviet studies, received a regular commission, and spent 11 years as an 0202 intelligence officer. He was course director and primary instructor for the Marine Corps’ Air-Ground Task Force Intelligence Officer Course from 1989 to 1992. He is a 1993 graduate of the Joint Military Intelligence College, receiving a master’s in strategic intelligence. He is a realtor in Littleton, Colorado.

1. Since the conclusion of the Civil War, friendly and chronically weak states, throughout the Western Hemisphere, aided in the collective U.S. national security. Unbelievably, now much of U.S. homeland security hinges on Canadian and Mexican border and port authorities, hence the creation of the Department of Homeland Security and Northern Command. Geographical realities remain inescapable. back to article

2. The 2002 National Security Strategy requires that DoD “ensure current military dominance is not challenged.” Furthermore, DoD’s “Joint Vision 2020”’s goal is “full spectrum dominance.” back to article

3. Osama bin Laden, the Taliban, and most radical Mujahedeen are Sunnis—radical Wahhabi Sunnis, avowed adversaries of Iranian and Iraqi Shiites. Shiites comprise only 10% of Islam, Sunnis the remainder. back to article

4. General Giulio Douhet’s vision has yet to be fully achieved. The harsh realities of tactical geography remain constraints of air power. back to article

5. The much-touted Air Expeditionary Force (AEF) concept is absolutely constrained by tactical geography (the timely procurement of secure land-based airfields, replete with all necessary support and security features and within a suitable distance from the joint operations area). The AEF concept seems like an overly convoluted substitute for an aircraft carrier or Marine expeditionary airfield. Logistically, the AEF is unsustainable without exponentially increasing the U.S. footprint, defeating its stated purpose. back to article

6. Network-centric warfare is completely dependent on skilled personnel. back to article