In the large town where the emperor's palace was, life was joyous and happy; and every day new visitors arrived. One day two swindlers came. They told everybody they were weavers and that they could weave the most marvelous cloth. Not only were the colors and the patterns of their material extraordinary, but the cloth had the strange quality of being invisible to anyone who was unfit for his office, or unforgivably stupid.1

In the January 1999 Proceedings, former Secretary of the Navy James Webb made the case that the Navy was allowed to shrink in both fleet size and personnel, because Navy leaders made no viable contrary argument to Congress and the public.2 In essence, they were silent as cuts were made. If the admirals were silent, they weren't alone.

Management has supplanted leadership in the naval services to some degree. The climate of risk avoidance is part of the problem, and it is evidenced by the officer corps' unwillingness to speak out when warranted. Too many officers are silently managing their own careers. In the Coast Guard and other services, personnel and parts shortages are the order of the day. Despite current political rhetoric, the armed forces are thin when it comes to soldiers, airmen, and sailors, and our capital assets are in dire need of replacement. How did we get here?

Culture

Commandant of the U.S. Coast Guard Admiral James M. Loy recently addressed "the curse of Semper Paratus."3 Semper Paratus translates to "always ready." Ever since the Coast Guard adopted the motto, and arguably long before, the service has had a "can-do" mentality. Whatever the mission, regardless of whether the Coast Guard had the needed personnel or equipment, the culture has been to get the job done despite any odds. Admiral Loy stated that "instead of saying, 'We can't do that job,' we take perverse pride in performing our missions with no money, old equipment, too few people, and seat-of-the-pants training." The Coast Guard's history is a proud one, and its people have lived up to the motto time and again when the country has called. Semper Paratus has been a "curse," however, because too often service leaders and members have remained silent when speaking up and admitting decreased readiness might have better served the Coast Guard and the public it serves. As the saying goes, "you can pay now, or you can pay later." The retention and recapitalization efforts necessitated in all the armed forces today reflect this toll. According to the Sea Power 2000 Almanac, "the Coast Guard's physical assets (cutters, aircraft, and shore facilities) have been undercapitalized for years. Only two of the 41 countries throughout the world with similarly sized navies or coast guards have an older physical plant." As a remedy, the service is working with industry in a far-reaching recapitalization effort called the Deepwater Project.

Soon the Emperor sent one of his trusted counselors to see how the work was progressing. He looked, but since there was nothing to be seen, he didn't see anything. "I am not stupid," thought the emperor's counselor. "I must be unfit for my office. That is strange; but I'd better not admit it to anyone." And he started to praise the material, which he could not see, for the loveliness of its patterns and colors.

Career Fear

The Commandant addressed the issue of "career fear" in a speech to the Chief Petty Officer's (CPO) Association on 16 August 1999. Admiral Loy defined it as "the reluctance on the part of career-minded military personnel to take necessary and prudent risks." He made the case that career fear is not pervasive in the Coast Guard because personal leadership at the CPO level prevents its spread, and because the service strongly supports the operational decisions its members make. In most respects the Commandant is correct. The Coast Guard has excellent leadership at the CPO level, and junior officers particularly benefit from it. It doesn't take long to recognize that chiefs have a unique license to raise the "BS" flag. In contrast, it seems the majority of the officer corps has no such license today. As a Coast Guard aviator, I am proud to say I have never experienced a situation where operational decisions in any way had to be balanced against "career fear." And yes, the Coast Guard does strongly support operational decisions. This is a powerful tool enabling operators to be flexible in their approach to prosecuting a mission, and reasonable and prudent operational risks are a way of life. However, career fear of another sort does indeed exist, and it strongly detracts from the exercise of leadership.

Leadership

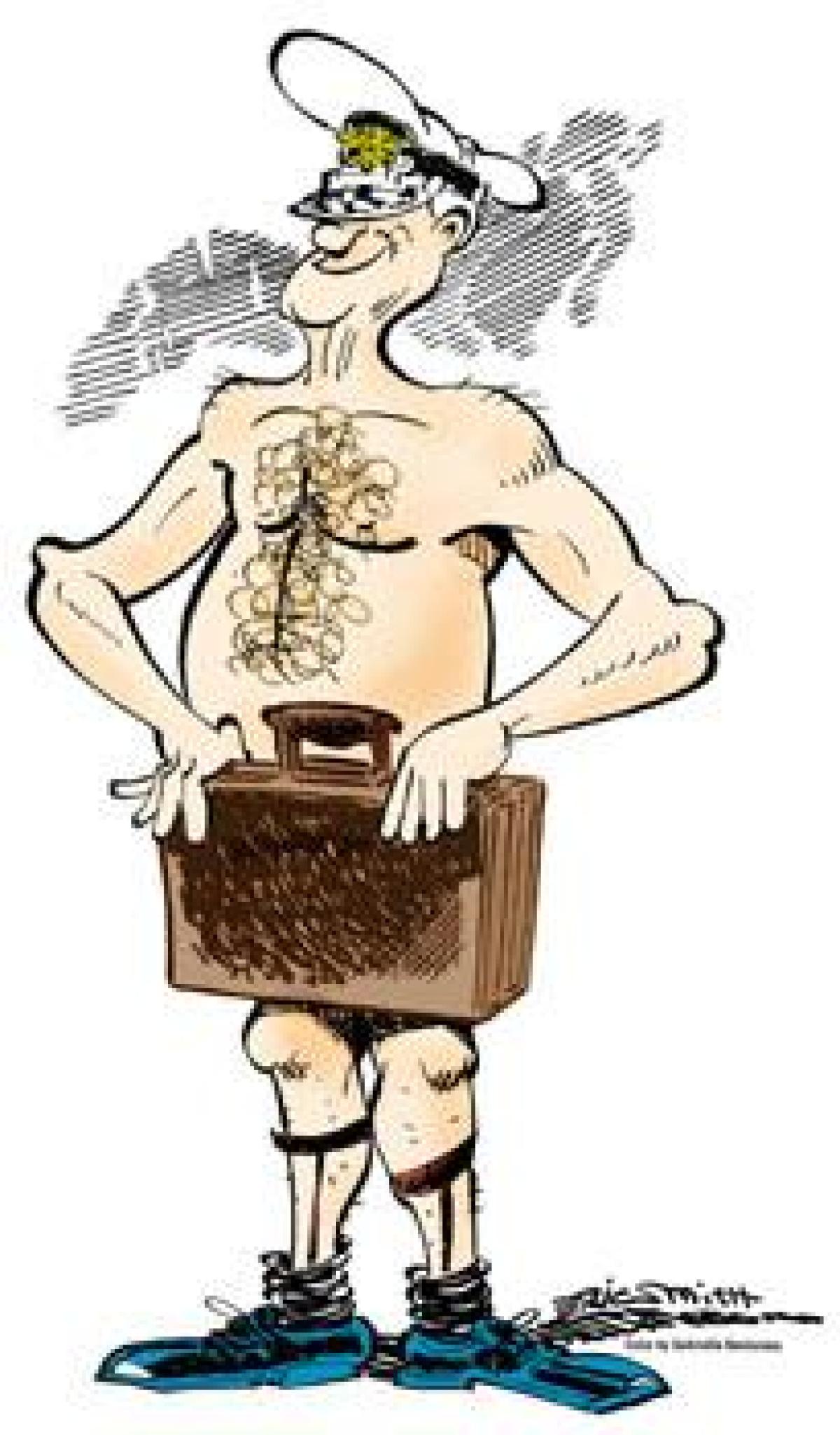

In his book The Art of the Leader, Major General William A. Cohen, U.S. Air Force Reserve (Retired), defines leadership as "the art of influencing others to their maximum performance to accomplish any task, objective, or project."4 Influence is a key word in this definition. Leadership cannot be exercised in concert with this definition unless people and their input are valued. This might sound obvious, but when an atmosphere exists such that fear of career repercussions prevents officers from speaking up, they cannot lead. In the typical wardroom, officers often grumble among themselves long after senior leaders depart. A recurring theme is that the emperor is naked.

God forbid anyone voices such sacrilege in the necessary forum. There is a general perception that one is likely to get crushed for anything other than parroting the party line—and as the cliché goes, perception is reality. This is not only paralyzing but also unfortunate, because subordinate officers and our enlisted airmen and sailors are looking for the very leadership defined above.

I'm not suggesting anyone make a habit of falling on his sword arbitrarily. Nor am I suggesting our senior leaders are naked. My point is that often we are asked for our input or opinions, and the resulting silence is deafening! How many times have you been to a staff meeting or presentation when no one asks a single question at its conclusion? I'd bet this irony is echoed in all the armed forces. As a general, Dwight D. Eisenhower's number one rule of leadership was "no non-concurrence through silence."5 It seems this rule has fallen from grace. If naval officers are to meet future leadership challenges, it's our duty to see it rise from the ashes. It would serve the public we represent as well as those with whom we serve.

In his book Rules and Tools for Leaders, Major General Perry M. Smith, U.S. Air Force (Retired), explains that effective leaders must avoid "group-think." He describes the "direct relationship between the thoroughness and openness of the decision-making process and the effectiveness of the implementation process."6 If our senior leaders are to guide us in the accomplishment of service missions, they must be receptive to our input, and we must in turn give our opinions. Our ability to influence those junior to us depends on it.

Our senior leaders may be privy to more information than we are, and no doubt make decisions based on the bigger picture, but they might not have looked at the situation from the perspective of the enlisted troops or understand the impact at the unit level. A junior officer might just have some information or perspective the boss does not have. Remaining silent thoroughly negates the right to complain. It detracts from both credibility and integrity, which in turn impact influence.

The Combat Model of Leadership

General Cohen bases his leadership theories on a "combat model." In his introduction to Patton on Leadership: Strategic Lessons on Corporate Warfare, by Alan Axelrod, General Cohen explains: "Battle is a worst case condition in which the risks are high, the uncertainty great, and the hardships and 'workplace conditions' unknown in any other field of human endeavor."7 Axelrod's book borrows heavily from General Patton's theories, writing, and accomplishments to provide guidelines applicable to the corporate world. Lessons of leadership forged in the heat of battle have stood the test of time, precisely because of the environment from which they came. Many other management books have borrowed from military leadership history to provide models for excellence.

Today, the military seems to have reversed the trend and borrows from corporate leadership models. Unquestionably, the armed services have benefited from corporate models. However, these theories can conflict with military service. For example, an effective corporate executive can more readily afford to be self-serving. Climbing the corporate ladder can be about maximizing personal utility, as evidenced by the executive pay scale. Make a simple comparison between any Fortune 500 company chief executive officer's salary and that of a flag officer. Corporate executives make business decisions that affect the bottom line. Their effectiveness is measured in profitability, which does affect the livelihood of employees. However, most business leadership theory gurus haven't faced the business end of an AK-47, dealt with shipboard life or deployments, or been involved in a life-and-death search-and-rescue case in extreme weather. Unquestionably, officers must make business decisions, but leadership decisions are what we are about.

Naval officers collectively should return to their roots. Focusing on personal career utility might be beneficial in the corporate world, but the potentially negative impact in the armed services is more obvious. Serving the needs of your unit, your service, and the U.S. public is more readily modeled by studying effective military leaders. The combat model is a good one. General Cohen outlines six ways to get the combat model to work for you 8:

- Be willing to take risks

- Be innovative

- Take charge

- Have high expectations

- Maintain a positive attitude

- Get out in front

The two gentlemen of the imperial bedchamber fumbled on the floor, trying to find the train, which they were supposed to carry. They didn't dare admit that they didn't see anything, so they pretended to pick up the train and held their hands as if they were carrying it.

Duty

General Douglas MacArthur's speech delivered at West Point on 12 May 1962 made famous the mantra of "Duty, Honor, Country." Of these hallowed words, the first is duty. If officers are to have the influence necessary to exercise leadership and to effect positive change in the naval services, they must do their duty and speak up when conscience dictates. If bad policy decisions go unchecked, wardroom members are guilty of condoning them. If officers complain about policy or decisions without having offered their concerns, they violate integrity.

If "the emperor is naked," then he or she would probably like to know it before standing before the world. If not, individual officers will readily know it through the perspective shared after questions or comments are offered. In the end, officers have the duty to carry out the orders and support the policies of senior leaders. It will be much easier to do without complaint if one follows the steps in the combat model. Take risks, be innovative by offering ideas and experience, take charge with a clear conscience, expect the best after taking ownership, be positive, and by all means lead from the front. General MacArthur would have expected nothing less. An excerpt from his speech expounds on the three words, "duty, honor, country":

They teach you to be proud and unbending in honest failure, but humble and gentle in success; not to substitute words for actions, not to seek the path of comfort, but to face the stress and spur of difficulty and challenge; to learn to stand up in the storm, but to have compassion on those who fail; to master yourself before you seek to master others; to have a heart that is clean, a goal that is high; to learn to laugh yet never forget how to weep; to reach into the future, yet never neglect the past. They teach you to be an officer and a gentleman.9

Looking toward the future leadership challenges stemming from recapitalization, reorganization, recruiting, and other efforts, naval officers should readopt General Eisenhower's rule as a way to avoid being part of the problem, and as a way to have the influence necessary to command effective leadership. It's time to end the silence of the wardroom and the career fear that causes it. The future depends on leadership, not management.

Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale reaches a climax when an innocent little boy announces "the emperor is naked." Until that moment of courage, the crowd of onlookers stood mute or vocally admired the beautiful clothes that weren't there at all. The group-think stemming from fear not only left the emperor exposed, but also diminished the credibility of all.

Lieutenant Wilson is an HH-65A Dolphin commander, serving as assistant engineering officer at Air Station Traverse City, Michigan. He is a 1993 graduate of the U.S. Coast Guard Officer Candidate School.

1. Hans Christian Andersen, A Treasury of Hans Christian Andersen, trans. Erik Christian Haugaard (Garden City, NJ: Doubleday Direct, 1972), pp. 81-82. (back to article)

2. James H. Webb Jr., "The Silence of the Admirals," Proceedings, January 1999, pp. 29-34. (back to article)

3. "The Curse of Semper Paratus," speech given by Admiral James Loy at Military Order of the Carabao Luncheon, 19 January 1999. (back to article)

4. Major General William A. Cohen, USAFR (Ret.), The Art of the Leader, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1990), p. 9. (back to article)

5. Major General Perry M. Smith, USAF (Ret.), Rules and Tools for Leaders (New York: Avery-Penguin Putman, 1998), p. 23. (back to article)

6. Smith, Rules and Tools for Leaders, p. 24. (back to article)

7. Alan Axelrod, Patton on Leadership: Strategic Lessons on Corporate Warfare, (Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall, 1999), p. xi. (back to article)

8. Cohen, The Art of the Leader, p. 17. (back to article)

9. The Moral Compass, Edited with commentaries by William J. Bennett (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1995), p. 693. (back to article)