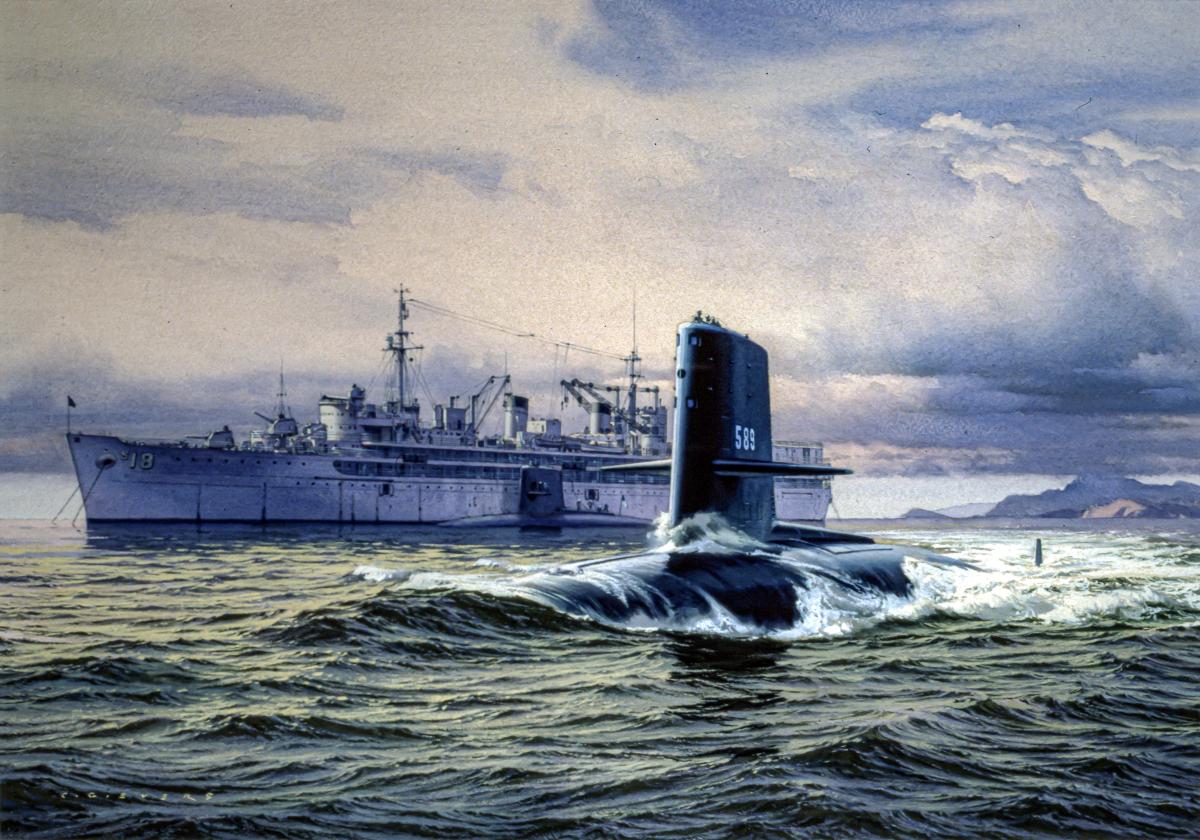

At around midnight on 16 May 1968, the USS Scorpion (SSN-589) slipped quietly through the Strait of Gibraltar and paused just long enough off the choppy breakwaters of Rota, Spain, to rendezvous with a Navy ship and offload two crewmen and several messages. A high-performance nuclear-propelled attack submarine with 99 men on board, the Scorpion was on her way home to Norfolk, Virginia, after three months of operations in the Mediterranean with the Sixth Fleet and NATO.1

Upon entering the Atlantic, the Scorpion came under the direct operational control of Vice Admiral Arnold Schade, Commander of the U.S. Navy’s Atlantic Submarine Fleet. On 20 May, he issued a still-classified operations order that diverted the submarine toward the Canary Islands and a small formation of Soviet warships patrolling southwest of the islands. Under U.S. naval air surveillance since 19 May, this flotilla consisted of one Echo-II-class nuclear-propelled submarine, a submarine rescue vessel, and two hydrographic survey ships. Three days later, a guided-missile destroyer, capable of firing nuclear surface-to-surface missiles, and an oiler joined the group.2

At approximately 1954 Norfolk time on 21 May, the Scorpion rose to within a few feet of the rolling surface and radioed the U.S. Naval Communication Station in Greece. Her radioman reported that she was 250 miles southwest of the Azores Islands and estimated her time of arrival in Norfolk to be 1300, 27 May.3 On the 27th, as families of the crew gathered on Pier 22, the captain of the USS Orion (AS-18), the acting commander of Submarine Squadron Six, the Scorpion's unit, told Admiral Schade what the admiral secretly already knew: the Scorpion had failed to respond to routine messages.4 After an intensive effort to communicate with the submarine failed, Admiral Schade declared a SUBMISS at 1515 and launched a massive hunt.5

What most in the Navy, including the crew’s families, did not know was that Admiral Schade already had organized a secret search for the submarine on 24 May after she failed to respond to a series of classified messages and, by the 28th, he and others in the service’s command believed the Scorpion had been destroyed. Highly classified hydrophone data indicated that she had suffered a catastrophic explosion on 22 May and had been crushed as she twisted downward to the ocean floor.6

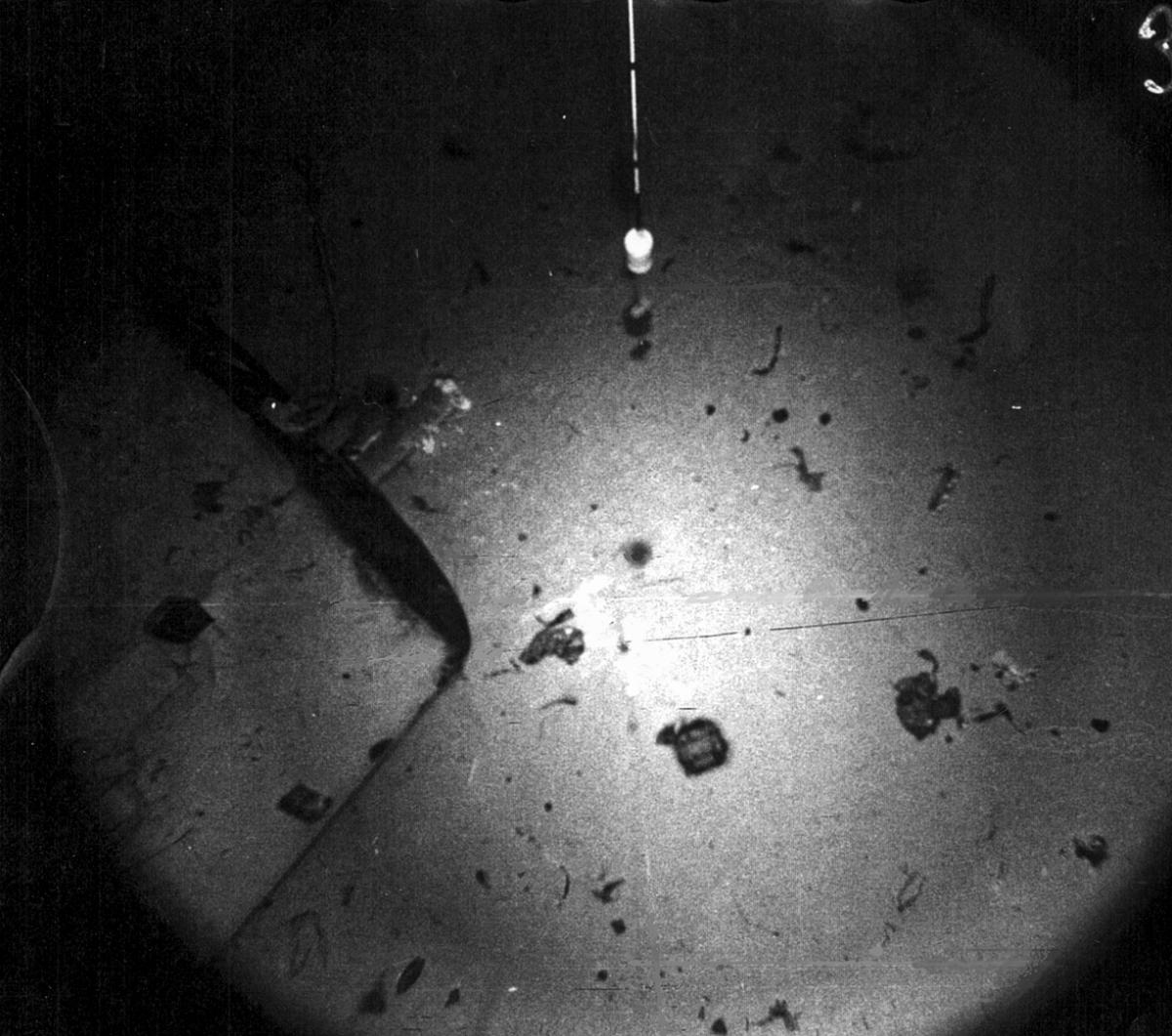

On 5 June, the Navy declared the submarine officially presumed lost and her crew dead and established a formal Court of Inquiry chaired by retired Vice Admiral Bernard Austin, who also had headed the Navy’s investigation into the 1963 loss of the USS Thresher (SSN-593), which cost the lives of 129 men.7 After adjourning on 25 July, the court concluded that it could not determine the cause for the Scorpion’s loss.8 On 28 October, the Navy found the Scorpion's shattered remains in more than 11,000 feet of water approximately 400 miles southwest of the Azores.9 On 6 November Admiral Austin reconvened his court, which studied thousands of photographs taken of the wreckage by the USNS Mizar (T-AGOR-11). After two more months, the court again could not determine precisely how the submarine had been destroyed.

Frustrated by this lack of clear answers, the Navy’s high command turned to the Trieste II, a specially designed deep-water submersible.10 Between 2 June and 2 August 1969, the bathyscaphe made nine dives to the Scorpion, photographing and diagramming her broken hull.11 Although these efforts provided a clearer view of her location and condition, they again failed to tell exactly what had happened. After 30 years, the Scorpion’s fate still remains shrouded in mystery.

According to the first Court of Inquiry’s sanitized declassified report, the Scorpion had been diverted to shadow a Soviet flotilla engaged in a “hydroacoustic” operation. This meant that the Soviets also were collecting and analyzing information derived from the acoustic waves radiated by unfriendly ships and submarines.12

The Soviets also may have been trying to gather intelligence on the U.S. Sound Underwater Surveillance System (SOSUS), an elaborate global network of fixed sea-bottom hydrophones that listened for submarines. By 1968, the United States had deployed a SOSUS network off the Canary Islands and was laying another off the Azores.13 Any Soviet attempt to disrupt or penetrate SOSUS would have aroused a great deal of interest in Norfolk. Another theory that could explain the decision to send the Scorpion toward the Canary Islands is that the Soviets may have been experimenting in early 1968 with ways to support their warships and submarines at sea, a potentially enormous shift in doctrine for a fleet that was forced to rely primarily on foreign ports to keep itself afloat.14

Whatever her last mission was, the Scorpion appears to have completed her operational phase by the time of her last broadcast.15 At the time of her last communication, she was approximately 200 miles or six hours away from the Soviet formation. Nearly 24 hours later, SOSUS and civilian underwater listening systems picked up an underwater explosion, followed by crushing sounds not unlike those recorded during the Thresher’s destruction. According to these readouts, the entire episode lasted slightly more than three minutes.16

Applying sophisticated mathematics to these recordings and tracing the Scorpion's presumed track and speed, the Navy designated an area of “special interest” for its search some 400 miles southwest of the Azores.17 On 31 May, the USS Compass Island (AG-153) was dispatched to conduct an underwater survey, and on 28 October, the Mizar finally found the wreckage.18

Deeply shaken and still reeling from the loss of the Thresher, the Navy began its postmortem with only the SOSUS readouts, the Scorpion’s operational history, and testimony of her former crew members. The first Court of Inquiry examined 76 witnesses as it considered a broad array of fatal possibilities. First among these was that the Soviets had intercepted the Scorpion and finished her in an undersea dogfight.19 The court discarded this theory after it examined reports the intelligence community provided and found no evidence to support it. The court also noted that no other Soviet or Warsaw Pact ships had been within 1,000 miles of her last reported position.

While the theory of Soviet involvement is tantalizing, it is highly unlikely that the Soviet Navy had the capability to hunt down the Scorpion. The Soviets still were relying heavily at that time on their vintage diesel Whiskey-class submarines. Slow and lacking advanced weapons and sophisticated electronics, the outdated Whiskeys were no match for the Scorpion.20

Similarly, although the Soviet Echo II-class nuclear-propelled submarine was armed with conventional antisubmarine torpedoes, her main weapons were surface-to-surface missiles. [In retrospect, the U.S. Navy did not begin to decommission Skipjack (SSN-585)-class submarines until 1986. Until then, five remained in first-line service, an improbability if the Soviets so easily had hunted down and killed the Scorpion nearly 20 years before.]21

After rejecting this scenario, the court similarly discounted sabotage, a collision with an undersea mountain, a nuclear accident, structural failure, a fire, an irrational act by a crew member, loss of navigational control, and, with far less certainty, a weapons accident. Although it found no direct evidence that one of the submarine’s own torpedoes had exploded, the court noted that on 5 December 1967 the Scorpion had confronted an accidentally activated Mark 37 torpedo in one of her firing tubes and had sidestepped disaster by expelling the torpedo before it could detonate.22 In May 1968, the Scorpion had 14 Mark 37s in an arsenal that included two Mark 45 Astor torpedoes with nuclear warheads and 7 other conventional projectiles.23

She also had a new commander. When he took over on 17 October 1967, Commander Francis Atwood Slattery was 36 years old. A former executive officer of the Nautilus (SSN-571), he was among a small cadre tapped for elite nuclear-propelled submarine duty.24

His inexperience showed in December, when Navy inspectors gave the Scorpion an unsatisfactory rating after she failed casualty drills involving her nuclear torpedoes and again in January when she engaged in an advanced submarine-against-submarine exercise and received the lowest tactical grade of all participants.25 Nevertheless, by the time she deployed to the Mediterranean in February 1968, the Navy rated her fully ready, and by March she was praised by the Sixth Fleet Command Staff for being a well-trained, well-run submarine.26 By April, 7 of her 12 officers and 61 of her 87 enlisted men were fully qualified in submarines, and the court found no grounds to blame any of her men for what happened on 22 May.27

In early November, Admiral Austin asked a special Technical Advisory Group, comprised of scientists and veteran submariners, to pore over the newly discovered physical evidence. Admiral Thomas Moorer, the Chief of Naval Operations, earlier had created this group to provide technical expertise to the court.28 Headed by Dr. John Craven and assisted by the Naval Research Laboratory, the technical experts first examined the acoustical recordings and made a startling discovery: the Scorpion had been heading east, instead of west toward Norfolk, when the first cataclysmic explosion detonated. The advisors estimated that the first sound to register on SOSUS had been caused by at least 30 pounds of TNT, exploding 60 feet or more below the surface, and theorized that the Scorpion had been engaged in a hastily ordered U-turn in a desperate attempt to disarm a hot-run torpedo that exploded and caused uncontrollable flooding.29 In an article published in The Virginian-Pilot & Ledger-Star, Craven indicated that the hot-run scenario was the only one that fit all the evidence.30

Craven also related that the photographs indicated the Scorpion’s torpedo room was still intact and had not been crushed by water pressure. In that interview, Craven said he believed the torpedo room did not implode, pointing out that it was the first part of the Scorpion to flood after the explosion and already had filled with water when the submarine began to sink. Noting the absence of visible damage from outside the hull, he added that a torpedo probably detonated inside the compartment instead of in one of the submarine’s six firing tubes.31

Craven also noted that the photographs showed several access hatches open to the torpedo room. This meant probably that they were pushed out by internal pressure.32 The other SOSUS recordings were sounds of the Scorpion’s various compartments collapsing and buckling as she sank below her crush depth and slammed into the ocean floor at approximately 25 to 35 knots.33

Although the court discovered that Admiral Schade’s 20 May operational order did not specify whether the Scorpion’s torpedoes were to be fully armed, it seems likely that Commander Slattery would have ordered them ready as she approached the Soviet ships. The court speculated that the Scorpion probably had begun disarming her torpedoes by the time she broadcast her final message on the evening of 21 May because of the Navy’s strict policy forbidding submarines from entering Norfolk with fully armed warheads.34 If so, the investigators theorized that something as simple as a short in a piece of testing equipment accidentally could have activated one of the Mark 37’s batteries and triggered a hot run. Left with only seconds to react, Commander Slattery would have ordered the Scorpion into the abrupt U-turn she was making when the torpedo exploded.

Almost immediately, the Navy’s Bureau of Weapons challenged the hot-run theory and commissioned its own study to undermine it. Admiral P. Ephriam Holmes, Commander-in-Chief, Atlantic Fleet, and Vice Admiral Schade supported the bureau’s position.35 Both pointed out that no torpedo damage to the Scorpion’s hull was visible in photographs, that her weapons room showed no signs of a cataclysmic explosion that would have followed as the warship’s torpedoes erupted in a massive chain reaction, and that her torpedo-firing tubes were not deformed. Moreover, former crew members were unable to identify any objects from her torpedo room in the debris field.36

Admiral Schade told the court that he believed the Scorpion simply was lost after she flooded and sank below her designed operating capacity. Although unsure of how the flooding started, he speculated that it happened while the submarine was at 60 feet, periscope depth, and that she already was full of water by the time she began to sink. In a letter to Admiral Austin, he wrote that he believed the most likely cause of the disaster to be an accident involving the submarine’s trash-disposal unit.37

Located in the galley, this unit consisted of an inner hatch separated from highly pressurized sea water by a basketball-sized valve connected to a 10½-inch tunnel. Although the inner hatch was supposed to be prevented from opening mechanically while trash was being flushed, and the crew was trained to use a bleed valve to make sure no pressurized sea water was outside before ejecting waste, a broken system or valve, coupled with a personnel mistake, could have unleashed high-pressure sea

water through the galley. Swamping her operations center, the rushing cascade would have overwhelmed her pumps, washed over and shorted out her electric control panels, and flooded her huge 69-ton battery several decks below, which then exploded into a deadly mist of fiery hydrogen and poisonous chlorine gas.

Retired Vice Admiral Robert Fountain, the executive officer of the Scorpion from 1965 until 1967, supports this theory. In a recent interview, he explained that the Scorpion normally came up to periscope depth to expel trash and that she especially would have needed to do so after an underwater intelligence operation. He also pointed out that the submarine had experienced previous flooding because of her trash disposal unit.38 Some of the photographs show that all the submarine’s identifiable debris came from her operations center, where her galley was located, and that a large section of her hull is missing where her main battery was stored.39

In fact, the Navy’s Structural Analysis Group (SAG)—a team of experts specially assembled in 1969 to review the evidence gathered by the Trieste II—published a lengthy classified study. It pointed to a battery casualty as the most likely cause for the submarine’s loss.40 Although it admitted that “it is not considered likely that conclusive evidence of the cause of the loss of Scorpion is possible with the evidence presently available,” the SAG based its findings on strong circumstantial evidence.41

The group concluded that the Scorpion showed no external torpedo damage, that her bow had not suffered an internal explosion, and that her hull had imploded only after she had passed below crush depth.42 Photographs also showed that she was near the surface sometime during the disaster, because her Number Two periscope, her loop antennae, and her helical whip all were raised, and her after escape hatch trunk access door was open.43 The experts also had statements prepared by three officers who had participated in the Trieste II's eighth dive. In these, the officers reported seeing what they believed to be a body dressed in dungarees or cloth trousers and wearing an orange kapok life jacket, lying in the silt near the bow.44

Thus, the SAG speculated that at least one crew member had tried to escape.45 The analysts also discovered acoustical evidence from Columbia University’s hydrophone station in the Canary Islands, indicating a possible sound event from the direction of the Scorpion approximately 22 minutes earlier than first thought. Its faint magnitude meant either that it was very small or that the Scorpion was at the surface when it occurred, or both.46

In addition, wreckage analysts from the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard in Maine examined the submarine’s debris field and found it littered with battery fragments.47 The debris revealed that the Scorpion's main battery was missing both the threads on its terminal posts and its cover seal nuts.48 This pointed to an explosion in the cells, which had blown off the battery’s covers completely. An analysis showed that they had been torn off violently from the inside. Similarly, the experts believed that the lodging of alumina particles in the platisol covers and scorching from a piece of mattress ticking indicated that the battery’s explosion had generated great heat and created enough force to damage the operations compartment, causing Unstoppable flooding and ultimately, the submarine’s loss.49

Although the analysts believed that it was impossible for all 126 cells to explode internally and that other items in the debris field indicated an explosion outside the battery well, they determined that a battery explosion best matched all the evidence examined.50 The SAG also considered whether massive flooding and even minor flooding could have triggered the chain of events leading to the Scorpion's loss and determined that either could have. The group determined, however, that no photographic evidence indicated massive flooding to be the culprit and neither the submarine’s engine nor her operations compartments was flooded completely when she passed her crush depth.51

The SAG reaffirmed this finding in 1987, when part of the original team reconvened to study photographs provided by Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute to the Navy in 1985. After reviewing the pictures shot by Jason, Jr., the swimmer camera, the SAG concluded that: “We observed nothing that could add more credence to or detract from our 1970 review findings. . . .”52

Admiral Austin’s court had considered both Admiral Schade’s theory and a battery explosion and determined that they were possible but “not probable,” without further comment.53 The court’s investigators found that the Scorpion's battery still had more than a year of guaranteed service life remaining and that it had produced 106% capacity when tested in January 1968.54 Moreover, several witnesses testified that they believed the warship’s safety systems would have deployed to save her if she were flooding that close to the surface.55 This assessment might have been right, if the Scorpion's safety systems were working fully and certified, but they were neither.

Her safety systems were direct products of the tragic loss of the Thresher. To combat criticism and regain prestige, the Navy instituted a Submarine Safety (SUBSAFE) Program designed to ensure that the Thresher disaster was never repeated. After months of exhaustive hearings, which produced 12 volumes and 1,718 pages of evidence. Navy experts traced the Thresher's sinking to a series of failed silver-braze joints and pipes that set into motion a deadly chain of events that ended with the warship’s main systems flooded and her ballast system unable to muster enough air to surface her.

In the wake of this, the Bureau of Ships and the Ship Systems Command placed depth restrictions on all post-World War II submarines—the Scorpion was limited to a depth of 500 feet instead of 700—and ordered their inspectors and workmen to begin the time-consuming and expensive task of examining and replacing faulty sea-water and hydraulic piping systems and rewelding possible faulty joints in more than 80 submarines. They also ordered the improvement of flood-control systems by increasing ballast-tank blow rates and the installation of decentralized sea-water shutoff valves.56

When the program was instituted, the Scorpion was in drydock at the Charleston Naval Shipyard for her first—and last—full overhaul. Arriving on 10 June 1963 and remaining until 28 April 1964, she nearly had completed her repairs by the time the yard’s command received orders to implement the new safety requirements. Although workmen inspected the Scorpion's hull and replaced many of her welds, they were not authorized to install emergency sea-water shutoff valves. Moreover, the Naval Ship Systems Command deemed the interim emergency blow system constructed by the yard unsuitable for service and ordered it disconnected. The Navy decided to defer installing these two systems until the Scorpion's next scheduled overhaul in 1967.57

By then, the Navy had spent more than $500 million on the program and estimated that it needed at least another $200 million more to certify all its submarines.58 Severe outside pressures also were forcing the Navy to rethink how best to allocate its already stretched resources.

Confronted with the need to launch more warships and to keep the ones it already had at sea, the Navy decided to delay installing full safety systems in many of its older submarines. This shift started with a series of confidential memoranda and messages drafted in 1966. A Naval Sea Systems Command study of that era revealed not only the rising costs of this program but that approximately 40% of the average submarine’s time was spent undergoing reconditioning instead of serving at sea.59

Clearly, Navy leadership was worried about the political fallout these statistics would generate. On 24 March 1966, the Commander of Submarine Squadron Six drafted a memorandum to Admiral Schade, admitting candidly that “The inordinate amount of time currently involved in routine overhauls of nuclear submarines is a recognized source of major concern to the Navy as a whole and the submarine force in particular and stands as a source of acute political embarrassment.” The memorandum blamed the Navy’s Bureau of Ships and shipyard managers and complained about the shortage of skilled workers needed to complete the overhauls, their poor planning in ordering critical materials on time, and the overall magnitude of what SUBSAFE required. It also warned that the Scorpion's next scheduled reconditioning in November 1966 “will establish a new record for overhaul duration.”60

This prompted the CNO, Admiral D. L. McDonald, to follow Admiral Schade’s request and approve the experimental “Planned or Reduced Availability” overhaul concept in the submarine fleet. In a 17 June 1966 message to the commanders-in-chief of both the Atlantic and Pacific fleets, Admiral McDonald wrote that, in response to “concerns about [the] percent [of] SSN off-line time due to length of shipyard overhauls, [I have] requested NAVSHIPS develop program to test ‘Planned Availability’ concept with USS Scorpion (SSN-589) and USS Tinosa (SSN-606).”61 On 20 July, the CNO officially approved the Scorpion's participation in this program.62 Expanding upon what the Navy command hoped this new plan would accomplish, Admiral McDonald’s successor as CNO, Admiral Thomas Moorer, wrote in a 6 September 1967 letter to Congressman William Bates: “It is the policy of the Navy to provide submarines that have been delivered without certification with safety certification modifications during regular overhauls. However, urgent operational commitments sometimes dictate that some items of the full safety certification package be deferred until a subsequent overhaul in order to reduce the time spent in overhaul. .. .”63 According to a 5 April 1968 confidential memorandum, the Navy did not expect the Scorpion to be certified fully under SUBSAFE until 1974.64

On 1 February 1967, the Scorpion began her “Reduced Availability” overhaul. By the time she sailed out on 6 October, she had received the cheapest submarine overhaul in U.S. Navy history.65 The retrofit of the USS Skate (SSN-578), Norfolk’s first nuclear-powered submarine, had gobbled up workmen and resources at an unprecedented rate, which meant that a submarine tender and the Scorpion's own crew had to perform most of the work done normally by yard workers. Out of the $3.2 million spent on her during these eight months, $2.3 million went into refueling and altering her reactor. A standard submarine overhaul of this era lasted almost two years and cost more than $20 million.66

When the Scorpion left for her Mediterranean deployment she was a last-minute replacement for the USS Sea Wolf (SSN-575), which had collided with another vessel in Boston Harbor. During her last deployment, the Scorpion had 109 work orders still unfilled—one being for a new trash-disposal unit latch—and she still lacked a working emergency blow system and decentralized emergency sea-water shutoff valves.67 She also suffered from chronic problems in hydraulics, which operated both her stern and sail planes. This problem came to the forefront in early-and mid-November 1967, when she began to corkscrew violently in the water during her test voyage to Puerto Rico and the U.S. Virgin Islands.68 Although she was put back in drydock, this problem remained unsolved. On 16 February 1968, she lost more than 1,500 gallons of oil from her conning tower as she sailed out of Hampton Roads toward the Mediterranean. By that time, many in the crew were calling her the “USS Scrapiron.”69

The Houston Chronicle published an article that highlighted these mechanical problems, quoting letters home from doomed crew members who complained about the deficiencies.70 Machinist’s Mate Second Class David Burton Stone wrote that the crew had repaired, replaced, or jury-rigged every piece of the Scorpion's equipment. On 23 March 1968, Commander Slattery drafted an emergency request for repairs that warned, among other things, that the “the hull was in a very poor state of preservation”—the Scorpion had been forced to undergo an emergency drydocking in New London, Connecticut, immediately after her reduced overhaul because of this—and bluntly stated that “Delay of the work an additional year could seriously jeopardize the Scorpion's material readiness.” He was particularly concerned about a series of leaking valves that caused the Scorpion to be restricted to an operating depth of just 300 feet, 200 feet more shallow than SUBSAFE restrictions and 400 shallower than her pre-Thresher standards.71

Although the SAG determined that the Scorpion's hull was in very good condition, it noted that an ultrasonic inspection conducted in late 1965 had uncovered 317 defects inside the warship’s internal welds. These caused the service to restrict her from receiving any target impacts on her hull during exercises. She was supposed to undergo more ultrasonic testing during her last overhaul, but this was cancelled.72

This portrait is sharply at odds with the one the Navy painted after the Scorpion was lost. At his first press conference on 27 May 1968, Admiral Moorer said that the Scorpion had not reported any mechanical problems and that she was not headed home for any repairs. Other subsequent Navy statements claimed that the Scorpion suffered only from a minor hydraulic leak and scarred linoleum on her deck before her Mediterranean deployment.73 On 29 May, then-Secretary of Defense Clark Clifford asked for information about the Scorpion.74

The Court of Inquiry subsequently asked several of its witnesses what they knew about the Scorpion’s mechanical condition and her maintenance history. Vice Admiral Schade told the court that her overall condition was above average and that her problems were normal, recurring maintenance items.75 Captain C. N. Mitchell, Deputy Chief of Staff for Logistics and Management and a member of Admiral Schade’s staff, supported his boss’s testimony.76

Captain Jared E. Clarke, III, Commander of Submarine Squadron Six, also told the court that the Scorpion was sound and “combat ready.” He said, “I know of nothing about her material condition upon her departure for the Mediterranean that in any way represented an unsafe condition.” When asked about the Scorpion’s lack of an operable emergency blow system. Captain Clarke replied that this was not a concern, because her other blow systems were more than adequate to meet the depth restrictions under which she was operating.77

Admiral Austin also summoned the two surviving crew members who had been offloaded for medical and family reasons on the night of 16 May 1968. When asked about any material problems, Joseph W. Underwood told the court that he knew of no deficiencies other than “a couple of hydraulic problems.” Similarly, Bill G. Elrod testified that the submarine was operating smoothly, with high morale. When asked to speculate on what did happen, Elrod could not. After hearing all this testimony, the court determined that the Scorpion's loss had nothing to do with her lack of a full SUBSAFE package and that both her ability to overcome flooding and her material condition were “excellent.”78 Although at least one of the dead crewmens’ families sent their sons’ letters spelling out the Scorpion’s poor state of repair to the Navy, no evidence indicates that the court ever received or considered them.79

Whatever the truth, the Scorpion’s loss triggered neither the klieg lights of the media nor the congressional investigations that followed the Thresher’s demise. The Navy added to the country’s amnesia by conducting its inquiries under a cloak of extraordinary secrecy. Even now, much about the Scorpion's fate remains highly classified and beyond public reach, and the crew’s 64 widows and more than 100 children know little more today about what happened to their husbands and fathers than they did 30 years ago. This gap between what is known and what is not has spawned many conspiracy theories.

A recent series of articles published in The Seattle Post-Intelligencer claims that the Scorpion was the victim of a possible Cold-War clash linked to the Walker spy case and an alleged agreement between the United States and the former Soviet Union to cover up a full accounting of what actually happened.80 According to the series, John Walker, a U.S. Navy warrant officer and leader of a Soviet-sponsored spy ring for almost 20 years, turned over the key lists and operating manuals to the KW-7, the Navy’s most secretive encryption device. Left with only half the answer of cracking the Navy’s codes, the series states that the Soviets persuaded the North Koreans to seize the USS Pueblo (AGER-2), a secret intelligence-gathering ship that was targeting the North Korean coast and Soviet naval units operating in the Tsushima Straits. When the North Koreans boarded her on 23 January 1968, they recovered at least 19 KW-7 machines. These were then passed to the Soviets, who used Walker’s stolen key lists and operating manuals to read the Navy’s most sensitive intelligence traffic, including classified messages that Admiral Schade sent to the Scorpion.81

The Seattle series speculates that Walker’s treachery gave the flotilla the means to know that the Scorpion was coming and claims that the Soviets not only tracked but possibly attacked her. In addition, it claims that Commander Slattery’s last message on 21 May 1968 to naval communicators in Greece did not say, as the Navy has long asserted, that the Scorpion had finished her intelligence operation but that she was just beginning it.82

The articles also theorize that the Scorpion’s loss is linked somehow to the Soviets’ loss of a Golf-II ballistic-missile submarine in April 1968 in the Pacific and quotes a retired U.S. naval attaché as stating that he was told by a Soviet vice admiral that a secret agreement had been reached between the United States and the Soviet Union in which both sides agreed not to press the other for details on the loss of either submarine and that those few in the know on both sides had been sworn to secrecy with the threat of maximum punishment.83

That Walker did enormous damage to U.S. security is indisputable.84 In May 1968 he was working as a watch officer in the Navy’s closely guarded submarine message center in Norfolk and, although much evidence indicates that Walker gave the Soviets potentially devastating intelligence about the Atlantic Submarine Force, nothing suggests that he played any direct role in the Scorpion’s demise or that his treachery led the Soviets to ambush her.

None of the photographs indicates that the Scorpion was hit by a torpedo or involved in a collision with another submarine. And no evidence supports the theory that the Soviet flotilla launched any weapons. In addition, U.S. intelligence agencies did not record any unusual traffic from these ships, nor did SOSUS pick up any torpedo explosions in the vicinity. Finally, the Scorpion’s wreckage was found hundreds of miles from the Soviet ships, which continued to operate in their same general area off the Canary Islands.85

Also unlikely is the scenario that the Soviets exercised enough control over the volatile North Korean leaders in 1968 to push them into risking war with the United States solely to make Walker’s purloined key lists functional. Even with that type of influence, the Soviets would have needed months to plan such an operation. According to intelligence debriefings, Walker did not steal these key lists until early January 1968, a mere couple of weeks before the Pueblo incident.86

Walker appears to have done much more damage when he passed on much of the top-secret traffic that came through the message center immediately after the submarine was reported missing.87 While it is tempting to blame the Soviets and Walker’s betrayal for this disaster, the probable truth is far different but no less disturbing.

Although the theory of a weapons accident has never been discounted officially, the physical evidence does not support it. None of the thousands of photographs taken of the wreckage shows any internal torpedo damage nor does the Scorpion’s approximately 3,000 feet by 1,800 feet debris field contain any items from her torpedo room.88

The most likely cause of the Scorpion's demise lies in the Navy’s failure to absorb the lessons learned from the Thresher. Admiral Hyman Rickover warned after that disaster that it would be repeated if the service did not correct the inadequate design, poor fabrication methods, and inadequate inspections that caused it. The SUBSAFE program was supposed to correct, maintain, and build a nuclear-powered submarine fleet that was both safe and effective. Unfortunately, the strains of competing with the Soviets in the Cold War while fighting an actual one in Vietnam derailed the concept.

After this tragedy, the Navy quietly dropped the Reduced Availability concept. In an article published by The Houston Chronicle, the Naval Sea Systems Command stated that it had no record of any such maintenance program.89 The reason for this may lie in a 25 March 1966 confidential memorandum from the Submarine Force: [The] “success of this ‘major-minor’ overhaul concept depends essentially on the results of our first case at hand: Scorpion.”90 Although the cause of her loss is still listed officially as unknown, the United States has never lost another nuclear-propelled submarine.

Author’s Note: In the 30 years since the Scorpion's loss, not one book has been written on the subject. The only newspaper articles written about her are eight by Ed Offley for The Virginian-Pilot & Ledger-Star and The Seattle Post-Intelligencer and four written by Stephen Johnson for The Houston Chronicle. The most important primary sources are the U.S. Navy Court of Inquiry Record of Proceedings and the Supplementary Record of Proceedings and the Structural Analysis Group’s study entitled Evaluation of Data and Artifacts Related to USS Scorpion (SSN-589), which was declassified earlier this year. In addition, the Naval Historical Center has more than 11 boxes of Scorpion-material currently available to researchers and expects to have more as already declassified material is cataloged. Although the CNO currently is considering the release of more Scorpion material, much still remains beyond the reach of researchers and the Freedom of Information Act. On 19 December 1997, the Navy denied my attempt to get copies of the first Court of Inquiry’s Annex. Those documents still retain their top-secret rating and are withheld because “of information that is classified in the interest of national defense and foreign policy.”

Stephen Johnson, a reporter for The Houston Chronicle, was the first to concentrate on the Scorpion's maintenance and overhaul history and was very generous with both his time and research. Vice Admiral Robert F. Fountain, U.S. Navy (Retired), former executive officer of the Scorpion, very kindly consented to an interview, as did Rear Admiral Hank McKinney, U.S. Navy (Retired), former Commander of the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Submarine Force.

1. Manual of the Judge Advocate General (JAGMAN) / U.S. Navy Court of Inquiry Record of Proceedings and the Supplementary Record of Proceedings Concerning the Loss of the USS SCORPION (SSN-589), (hereafter called Inquiry Record and Supplementary Record), p. 1043. The Scorpion participated in two operations in the Mediterranean: Dawn Patrol and Easy Gambler.

2.Inquiry Record, pp. 1043, 1046. U.S. Navy planes resumed surveillance of this formation on 21 May, presumably after the Scorpion had completed her own operation. The Soviet ballistic-missile destroyer and oiler did not arrive until the Scorpion already was 200 miles to the west of the formation.

3. Ibid. Although still classified, the Scorpion's final broadcast is said to have occurred at 31:19 north latitude, 27:37 west longitude. Ed Offley, “The Death of the Scorpion,” The Virginian-Pilot & Ledger-Star, 12 June 1983.

4. Ibid.

5. Inquiry Record, p. 1043

6. Offley, 12 June 1983. Admiral Schade’s claim that he became concerned about the Scorpion after her failure to respond to several messages is one of the strangest in this disaster. The Scorpion was under strict orders to maintain radio silence unless absolutely necessary. As a witness before the Court of Inquiry, he admitted that the Scorpion was not expected to respond to any messages and that he did not expect to hear from her until 27 May, the day she was supposed to arrive in Norfolk. Moreover, it was common during this era for a submarine to receive messages but be unable to respond because of broadcast difficulties. Because of this, it was not unusual for a submarine not to respond to incoming traffic. A more likely explanation for Admiral Schade’s statements is that he did not want to disclose that the SOSUS readouts indicating that the Scorpion had been destroyed were known earlier than reported.

7. Inquiry Record, p. 1049. The court actually was established on 4 June, one day before the Navy officially declared the Scorpion lost and her crew dead.

8. Ibid., p. 1082. See also “Third Endorsement of Chief of Naval Operations to Secretary of the Navy,” dated 29 March 1969.

9. Supplementary Record, p. 244.

10. “Third Endorsement from Chief of Naval Operations to Secretary of the Navy,” dated 29 March 1969.

11. Evaluation of Data and Artifacts Related to USS Scorpion: Prepared For Presentation to the CNO Scorpion Technical Advisory Group by The Structural Analysis Group, 29 June 1970 (hereafter referred to as SAG Report), pp. 2, 3.

12. Ed Offley, “USS Scorpion: Mystery of the Deep in Which 99 Were Killed,” The Seattle Post-Intelligencer, 20 May 1998.

13. Jeffrey T. Richelson, The U.S. Intelligence Community (Cambridge: Ballenger Pub. Co., 1989), p. 207.

14. Offley, 20 May 1998.

15. Inquiry Record, p. 1047.

16. Eight SOSUS stations picked up these recordings. Supplementary Record, p. 241. The actual length of the recordings was three minutes and ten seconds. See Inquiry Record, p. 1047.

17. Ibid.

18. SAG Report, p.1.1.

19. Court of Inquiry, pp. 1046 and 1047.

20. The Whiskey had a top speed of 15 knots while submerged. See John E. Moore, ed., Jane’s Pocket Book of Submarine Development (New York: Collier Books, Macmillan Publishing Co., 1976), p. 201.

21. In 1986 the Snook (SSN-592) became the first Skipjack-class submarine to be deactivated. Among the most bizarre episodes involving the Scorpion's loss, and dutifully reported by the Defense Intelligence Agency, was the statement by Jean Dixon, the soothsayer, who claimed she had experienced a vision in which the Soviets destroyed the submarine.

22. Inquiry Record, p. 1058.

23. Inquiry Record, p. 1057.

24. Officer Biography Sheet. In an anecdote related by Stephen Johnson, Slattery wrote a short story while in high school, forecasting his death in a submarine.

25. Inquiry Record, p. 1052.

26. bid.

27. Ibid., p. 1053. The court also determined the loss was not caused “by the intent, fault, negligence, or inefficiency of any person or person in the naval service or connected herewith.” See Supplementary Record, p. 256.

28. SAG Report, p. 1.1.

29. The first “acoustic event” had a signal greater than a 30-pound TNT charge detonated at a depth of 60 feet or more. Inquiry Record, p. 1079. Elsewhere, however, the same report states that “the amplitude of the first event was greater than the amplitude of a 70-pound charge detonated at 60 feet and less than a 70-pound charge detonated at 1,500 feet.” Ibid., p. 1048.

30. Ed Offley, “Mystery of Sub’s Sinking Unravels,” The Virginian-Pilot & Ledger-Star, 16 December 1984. Although no clear explanation has been advanced as to why the Scorpion may have been headed in an easterly direction during her final moments, possibilities are she may have been heading for shallower water, or she might have spun out of control after her crew became incapacitated. ‘‘Ibid.

31. Ibid.

32. Supplementary Record, p. 253.

33. Inquiry Record, p. 1083. The Inquiry Record—before the Scorpion's wreckage was found—listed the most probable cause of the loss as the submarine’s being struck by one of its own torpedoes after confronting a “hot run” and expelling it out of one of its firing tubes. The theory that a short in a piece of testing equipment could have triggered a hot run is detailed in Ed Offley’s article of 16 December 1984.

35. “First Endorsement on Vice Admiral Bernard Austin From the Chief of Naval Operations to Judge Advocate General,” dated 31 December 1968. See also Offley’s article of 16 December 1984, and Stephen Johnson, “A Long and Deep Mystery: Scorpion Crewman Says Sub’s ‘68 Sinking Was Preventable.” The Houston Chronicle, 23 May 1993, and Supplementary Record, p. 249.

36. Supplementary Record, p.250.

37. Johnson, 23 May 1993. Admiral Schade doubted that the first “high-energy” event recorded by SOSUS was an explosion. He speculated that the first sound was that of the engine room telescoping and imploding.

38. Interview with retired Vice Admiral Robert F. Fountain by author on 6 September 1997. See also Johnson, 23 May 1993, which points out that several other nuclear-powered submarines of that era almost sank because of trash disposal unit floods.

39. Supplementary Record, p. 250. See also Johnson, 23 May 1993.

40. SAG Report, p. 1.2.

41. Ibid.

42. Ibid., pp. 7.1–7.8.

43. Ibid.

44. The three statements are from: Lieutenant R. E. Saxon to Commander Submarine Development Group One, 16 February 1970; From Lieutenant D.T. Byrnes to COMSUB DFYGRU, 25 February 1970; and From Lieutenant John B. Field to Captain R. H. Gautier, 26 February 1970.

45. SAG Report, p. 8.1.

46. The most likely pattern was a faint sound 22 minutes before the first sound was recorded by SOSUS at approximately 1844. The second sound followed approximately 26 seconds later. The second as followed approximately 91 seconds later by 13 more. The explanation for the 1844 recording has ranged from a torpedo erupting inside the submarine to her hull imploding. SAG Report, pp. 5.1–5.4.

47. Ibid., 5.17

48. Ibid. See also Marty Lussier, “The Scorpion Revisited,” American Submariner: Submarine Review, No.2, April–June 1995, pp. 20–21. According to a letter written by Bob Dwinnel of Mare Island base, in response to Lussier’s article, hydrogen gas would have been produced only during the finishing rate of a battery charge or during a period of high discharge rate. See “Forum,” September 1995, American Submariner. The Scorpion's battery would have been experiencing a high discharge rate while she was near the surface and using her periscope and communication gear.

49. SAG Report, pp. 5.17–5.18; 7.2; and 7.7.

50. Ibid., 7.8.

51. Ibid., 7.6. The Scorpion's crush depth was probably around 1,100 feet. The Thresher's was 1,300 feet.

52. 14 January 1987 Letter from Peter M. Palermo, Chairman of SAG.

53. Ibid., p. 255. Indeed, the court did not consider the trash disposal unit to be the likely cause of serious flooding. Inquiry Record, p. 1087. NavShips rated the possibilities of explosions from the Scorpion's various sources. It ranked the possibility of a hydrogen gas explosion—presumably a spontaneous explosion—as “very low” and a weapons accident as “unlikely.”

54. Inquiry Record, p. 1075.

55. The court determined that the Scorpion's flooding recovery capability was excellent. Inquiry Record, p. 1086.

56. Unsigned Confidential Memorandum, entitled “Submarine Safety Program Status Report”; another undated, unsigned one-page memorandum entitled “SUBSAFE PROGRAM”; and a 5 April 1968 confidential memorandum entitled “SUBSAFE SAFETY PROGRAM” under the name of Lieutenant Commander W. T. Hussey. OP-312E, X76-191. All three of these were found by the author in the Scorpion files at the Naval Historical Center in Washington, D.C.

57. Details of the Scorpion's overhaul history are found in several sources: Inquiry Record, pp. 1042, 1066–1069; confidential memorandum for the record dated 28 May 1968, and signed by Captain Carl F. Turk; and an undated, unsigned confidential memorandum tracing the Scorpion's operational and maintenance history from January 1967 until 16 May 1968. The last two were found in the Scorpion files at the Naval Historical Center.

58. Hussy Memorandum, 5 April 1968.

59. Stephen Johnson, “Sub Sank in 1968 After Skimpy Last Overhaul/USS Scorpion Was Lost With All on Board,” The Houston Chronicle, 21 May 1995.

60. Confidential memorandum, 24 March 1966, Subj: “SSN Overhaul Policy; Comments On,” signed by P. P.Cole. In addition, this memo noted that the Scorpion's scheduled overhaul in Norfolk would overlap with the USS Shark (SSN-591), that of the USS Triton (SSN-586) and that of the first major overhaul and conversion by that yard of an SSBN, the Andrew Jackson (SSBN-619). It also observed that the Norfolk Naval Yard recently had entered the nuclear-powered submarine overhaul business and that much of the work needed by the Andrew Jackson would be novel and demanding. Stephen Johnson provided a copy of this memorandum.

61. Naval Message from CNO to CinCLantFlt and CinCPacFlt, 17 June 1966.

62. Unsigned undated message. Ref: (a) ComSubLant ltr ser 1008 of 2 Mar 1966; (b) NavShips 2nd end. Ser 525-1004 of 17 Jun 1966; CNO message 202135Z July 1966; and ComSubLant message 221858Z Jul 1966. Stephen Johnson provided a copy of this message.

63. Letter from Admiral Thomas H. Moorer to Hon. William Bates, United States House of Representatives, 8 September 1967. A copy of this letter went to South Carolina Senator Mendell Rivers, a legislator keenly interested in defense matters and a zealous advocate of the Charleston Naval Shipyard.

64. Hussey, 5 April 1968, confidential memorandum. Tab A, “Status of Depth Restrictions and Certificates.”

65. Johnson, 21 May 1995. 28 May 1968 confidential memorandum for the record by Captain Carl F. Turk. The actual figures for the Scorpion's reduced overhaul were $2 million for refueling, $0.3 million for nuclear alterations and $1 million for repairs. Her first and last full overhaul in Charleston cost $3,729,760. $1,277,140 of this went into what SUBSAFE work the yard was able to do. See Inquiry Record, p. 1066. According to the Turk memorandum, 23,000 man days were spent on the Scorpion, compared with 40,000 spent on the USS Skipjack (SSN-585), which received a full SUBSAFE package. When all these figures are added, the Scorpion, in both her overhauls, received about one quarter of the funds expended on several of her sister ships.

66. Johnson, 23 May 1993 and 21 May 1995; Turk, confidential memorandum for the record, 28 May 1968. In several documents, the Scorpion's 1967 overhaul is characterized simply as a “Refuel Overhaul.”

67. Inquiry Record, p.109. The trash disposal latch work order was found at the Naval Historical Center.

68. Ibid., p. 1072. See also Johnson, 23 May 1993. The court noted that “the stem plane control system constitutes one of the most potentially hazardous systems affecting the safe operation of high speed nuclear submarines.” Inquiry Record, p. 1092.

69. Johnson, 23 May 1993.

70. Ibid.

71. Confidential Memorandum from Commanding Officer, USS Scorpion, to Commander Submarine Squadron Six,” dated 23 March 1968. This memorandum was provided by Stephen Johnson. Among the valves Commander Slattery was concerned about were the sea valves and main ballast tank vent valves.

72. SAG Report, pp. 3.8–3.9. She did, however, receive the standard magnetic particle inspection on her hull’s surface.

73. ubmarine Warfare Division: Series III, Box 13, News Releases about Search Operation; Miscellaneous Correspondence on Search, Naval Historical Center, Washington, D.C.

74. Ibid. File “Information on Final Report to the Secretary of Defense.”

75. Submarine Warfare Division: Box 5, Series 1, Declassified Testimony from Court of Inquiry, Vols. 1–4.

76. Ibid.

77. Ibid. On 4 April 1968, Clarke wrote a memorandum about the Scorpion's Planned Availability Concept (PAC) to the Commander of the Naval Ship Systems Command. In it, he wrote: “It is recommended that those portions of SCORPION maintenance, repair and modernization work not covered by shipyard PAC be carefully considered prior to implementation of PAC. This review should have as its primary goal the avoidance of a situation which requires additional industrial assistance to forces afloat to keep SCORPION's material readiness equal to that of her sister ships.” Stephen Johnson provided a copy of this memorandum.

78. Ibid.

79. Johnson, 23 May 1995.

80. Offley, 20 May 1998.

81. Ibid. Offley wrote another article that same day entitled “Scorpion May Have Been Doomed Before It Even Set Out.”

82. Ibid.

83. Ibid. In April 1968, the Soviets lost the Golf-II in the Pacific Ocean. In 1974, this sunken submarine became the target of a highly ambitious clandestine operation by the CIA, using the deep-sea recovery ship Glomar Explorer. As far as is known, the CIA recovered the submarine’s forepart but whether any SS-N-5 SLBM missiles—the real targets—were recovered is unknown.

84. Pete Early, Family of Spies (New York: Bantam Books, 1988), pp. 68–69, 72–73, and 75–76.

85. See Inquiry Record, pp. 1046–1047.

86. Early, p.72.

87. Ibid., pp. 75-76.

88. Supplementary Record, pp. 245, 250, and 255. Indeed, the inquiry concluded “That in view of the lack of identifiable debris from the Torpedo Room, it is concluded that the Torpedo Room was not the location of a major explosive event.” The SAG Report (p. 5.13) states that the debris field measured approximately 800 feet north and south by 400 feet east and west.

89. Johnson, 27 December 1993.

90. Confidential Memorandum To File, dated 25 March 1966, USS Scorpion (SSN-589) Overhaul/Refueling Fact Sheet #1. This memorandum, signed by “H. L.Young,” also mentions the “mute skepticism” of many who question the practicality of the reduced overhaul concept and the need of “selling” this concept to the Navy’s Bureau of Ships and the Norfolk Naval Shipyard.