On 3 July 1988, the guided-missile cruiser Vincennes (CG-49), on patrol in the Persian Gulf, shot down an Iran Air Airbus, Flight 655, killing all 290 passengers and crew. This incident—analyzed in detail immediately afterward—clearly illustrates both the capabilities and the inherent limitations of modern weapon systems, particularly when they are used in scenarios different from those for which they were designed.

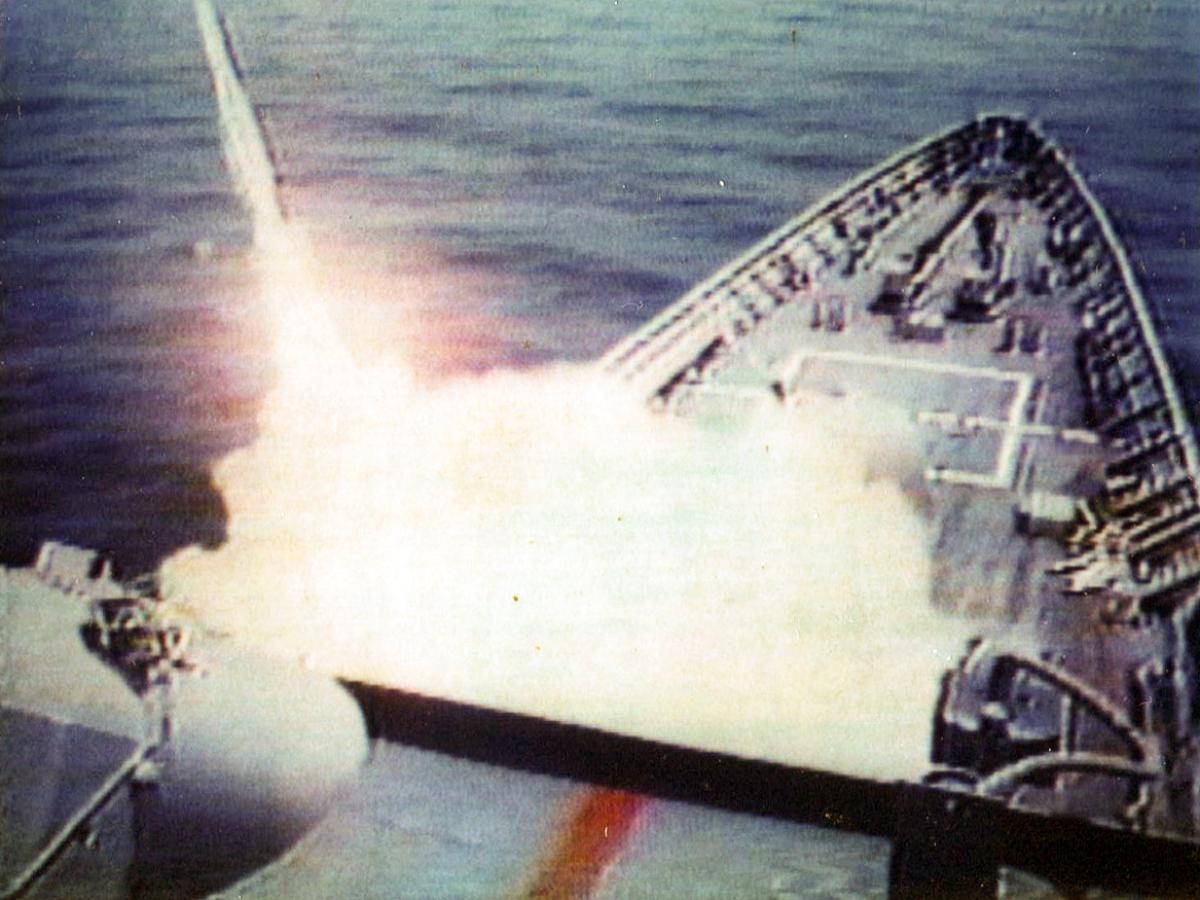

The missile cruiser is equipped with the Aegis weapon system, which is built around an electronically scanned SPY-1A radar, an unusually clear display system (four large-screen displays), and the Standard missile. (The ship carried SM-2 Block II missiles during the engagement.) The SPY-1A radar automatically detects and tracks any air target in its vicinity, filtering out “false” targets—ones that are not moving in a physically intelligible way.1

SPY-1A and the Aegis system were designed primarily for fleet air defense in a dense, high-speed environment, such as the Norwegian Sea. The system gives the ship an unusually clear two-dimensional (range and bearing) picture of air activity out to a considerable distance, and it automatically computes engagement orders for all the targets it tracks. That makes it possible for the ship to engage any of the targets with little delay, once the target has been identified as hostile. Since the system is intended for use in a high-threat environment, emphasis is placed on quick and accurate identification of friendly aircraft—which can be expected to make special efforts to avoid being shot down, such as flying along preselected corridors that can be laid down on the large-screen displays—and engagement of hostile contacts.

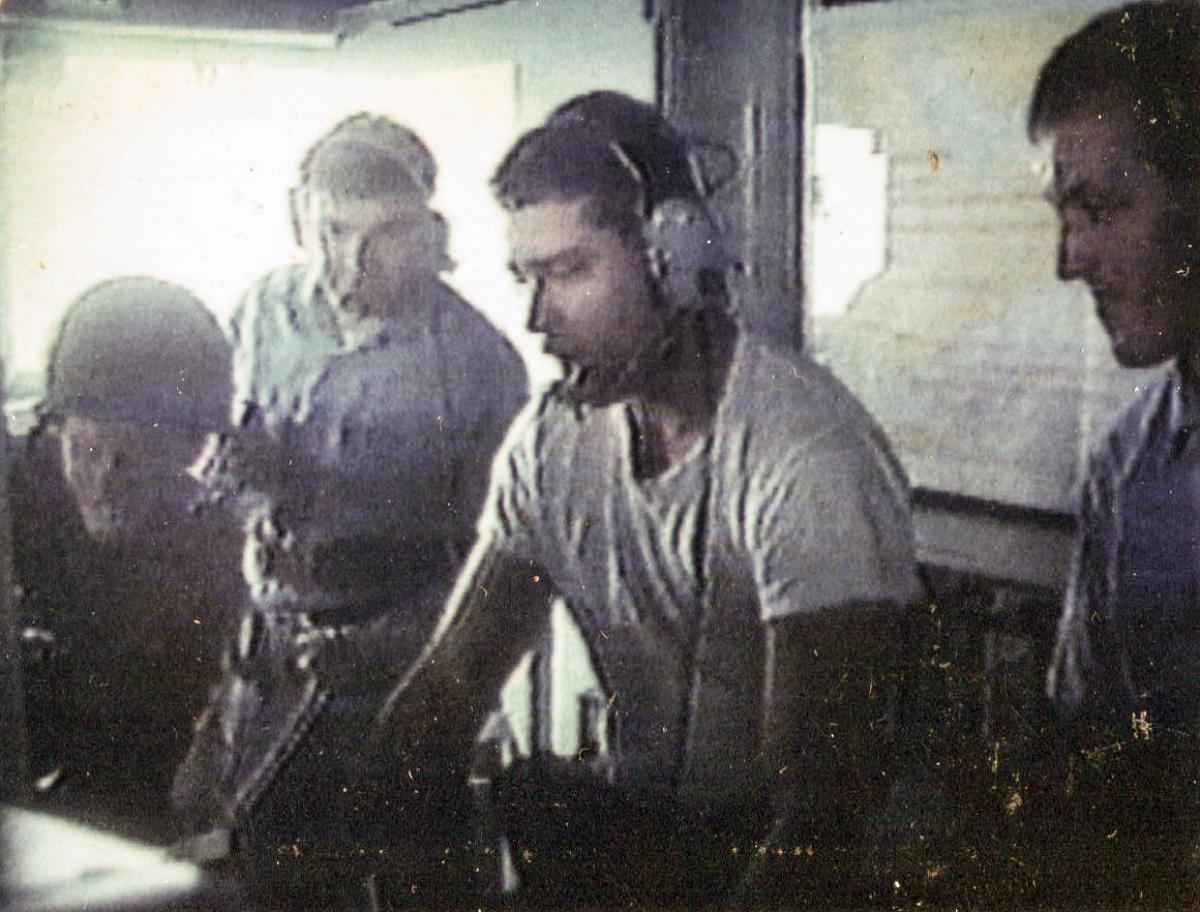

For a given target, the large-screen display shows only a vector, giving course and speed (not altitude, since the display is necessarily two-dimensional).2 It is up to combat information center (CIC) personnel to decide just what the target is, and typically they begin by tagging it as an unknown, with a track number or “TN.” In a hostile area such as the Persian Gulf, unknown often must equate to “probably hostile.” From the moment of detection until it faded from the radar, the Vincennes's CIC identified Iran Air 655 only as unknown TN 4131. TN 4131 closed steadily on a constant bearing: it seemed to be flying directly toward the Vincennes on a classic attack path. Moreover, while TN 4131 closed, the ship was engaging two Iranian gunboats. Given the overall situation, the men in the CIC, including the ship’s captain. Will Rogers III, had good reason to believe that it might be an Iranian aircraft about to attack them. The issue then became how long they had to identify TN 4131 before firing.

Although the radar performs surveillance well (as demonstrated, for example, both off Lebanon and during the 1985 Achille Lauro incident), it is primarily a means of effective fire control, and the design is probably biased in that direction, naturally. In particular, the integration of the radar with its associated identification friend or foe (IFF) system was not very strong. For example, the IFF operator had to move a range gate manually to track an incoming target. He could, therefore, accidentally associate the IFF response of one aircraft with another.

All current IFF systems use interrogators and transponders. The interrogator, which typically has a wider beam than the associated radar, sends a coded signal, and the transponder (which is omni-directional) replies. Responses can be in various modes and include a four-digit code. In this case, Mode II was associated with Iranian military aircraft and Mode III with civilian aircraft, although during the inquiry it was stated that Iranian military aircraft used both Modes II and III.

The Vincennes had been in the Gulf since 16 May, having been detached from a fleet exercise (FleetEx 88-2) on 20 April. She had undergone a variety of refresher training, including special exercises for Middle East Force ships that covered air intercept and antimissile defenses; terrorist aircraft training against, for example, the threat posed by a non-military aircraft on a kamikaze-type mission; and terrorist small boat and antiswimmer defenses.

The entire U. S. Middle East Force was alerted to a possible Iranian attack—including a suicide air attack—during the 4 July weekend. Iranian activity had been increasing for some time, and the Iranian government was under pressure to show some response to Iraqi victories on land. Given the widespread assumption in the Iranian government that the United States was backing Iraq, it would have been logical to assume that an attack on U. S. forces would have been an appropriate reaction. During the period immediately before the 4 July weekend, Iranian F-14 fighters began flying from the Bandar Abbas airfield.

The Vincennes detected Iran Air 655 just after it took off, about 47 nautical miles from the cruiser. It was never identified. Because the cruiser was almost directly under one of the boundaries of the commercial airline route from Bandar Abbas to Dubai, an airliner flying along the corridor (but off-center) would necessarily be a radar target closing steadily on a constant bearing. In other words, the contact would seem to be threatening the ship. That would not necessarily cause the ship to shoot it down, but it would be an important consideration in the crew’s monitoring of the target.

Iran Air 655 was not alone in the air over the Gulf. There were U. S. aircraft, including at least one AWACS (airborne warning and control system) aircraft and one E-2C Hawkeye. More significant, especially for the picture building in the Vincennes's CIC, there was an Iranian P-3, which had closed from about 60 to about 40 nautical miles. When challenged, the P-3 replied that it was going about its business and would not be approaching either the Vincennes or the other ships in the cruiser’s task group.

Iranian capabilities had to play a large role in what followed. Iran did not possess long-range, air-launched Exocet missiles, and its attacks on surface ships had generally been executed using Maverick missiles, television-guided weapons with a range of 0.5 to 13 nautical miles. It was known that Iran’s F-14s could drop unguided (iron) bombs, if they could approach to within two nautical miles of a target, and U. S. crews in the region suspected that the F-14s had been wired to launch Harpoon missiles, a few of which Iran had received before U. S. arms deliveries ceased in 1979. Given the widespread use of suicide tactics among Iranian-backed irregulars in Lebanon, U. S. crews also must have suspected that the Iranians might try a kamikaze attack on a ship.3

Captain Rogers would also have been aware that a large air force might prefer to use a stand-off aircraft like the P-3 to provide target information for the attacker, who would have to close the target (with its defenses) in order to attack. The official report about the incident describes the P-3 as flying a typical targeting profile (that is, standing clear of the target but remaining within radar range). The report does not indicate whether the P-3 was using its radar, but it seems likely that it was.4

Lastly, all ships in the Gulf were subject to attack by small fast craft manned by the Iranian Revolutionary Guards Corps (IRGC) and armed with rockets and infantry antitank weapons. Although such craft could not sink the Vincennes, they could do sufficient topside damage—knocking out her radar and missile systems, for example—to open her to a coordinated air attack.

The attack on the USS Stark (FFG-31) in May 1987 had demonstrated that Gulf War combatants would not necessarily make unusual efforts to identify large naval targets before attacking. Moreover, if the Iraqis, who were benefitting from U. S. friendliness, had attacked—accidentally or not—a U. S. warship, the Iranians, who blamed the “Great Satan” for their problems (and who had already lost a major battle to U. S. naval forces in April) were certainly much more likely to attack.

Early on 3 July, the Vincennes launched her LAMPS III helicopter to investigate a report of small Iranian gunboats. The craft fired at the helicopter, and the cruiser moved into position to drive them off; the helicopter then returned to the ship. The boats, which were faster than the cruiser, did not leave the area even after the cruiser began to fire. (Experience showed that such boats were most dangerous during high-speed passes close to ships.) After requesting permission from Commander Middle East Force, the Vincennes engaged the boats, which were closing at high speed. Later bullet damage was found on the cruiser’s starboard bow.

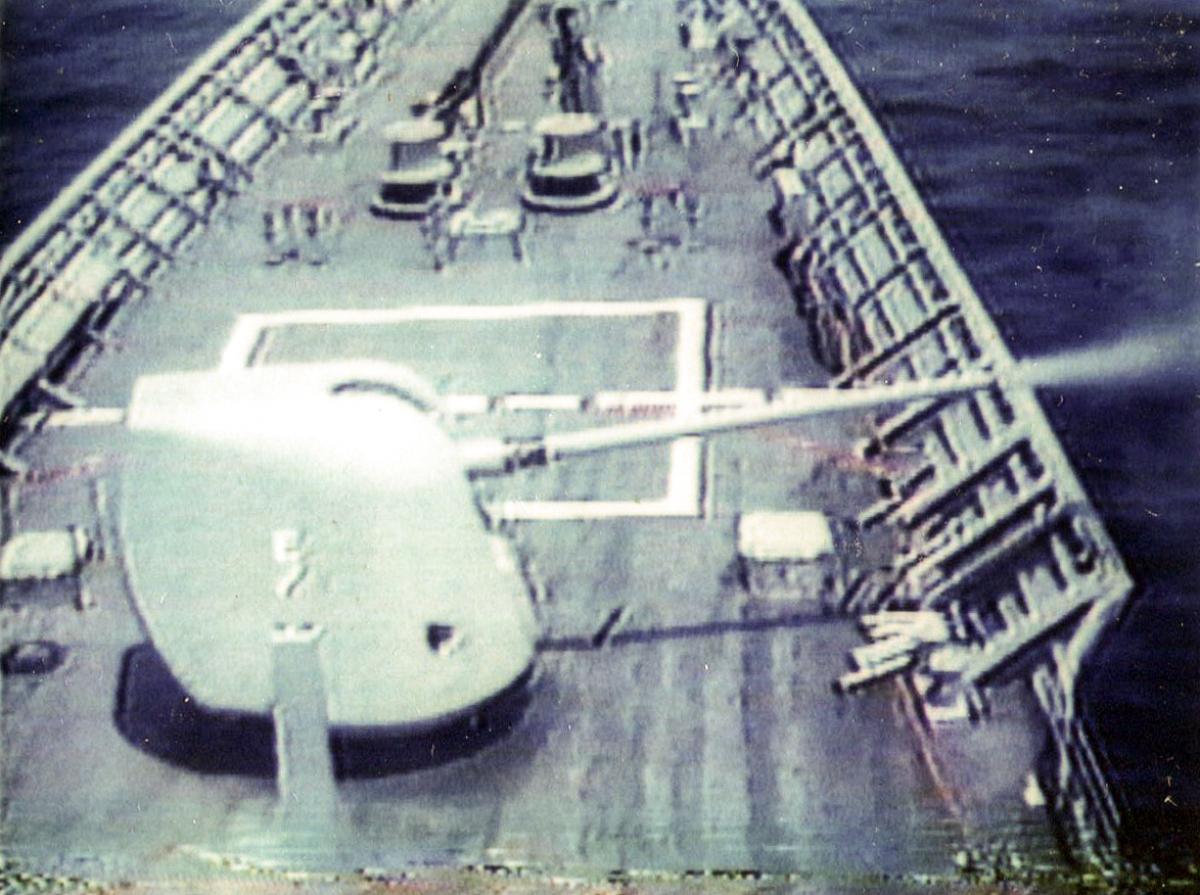

The Vincennes has two Mk-45 5-in./54-cal. guns and two Phalanx close-in weapon system (CIWS) defensive guns; the latter cannot engage surface targets.5 On this particular day, the forward 5-inch gun mount failed after one minute: a round had been chambered but would not fire.6 That left only one gun mount to engage as many as four surface contacts. The ship had to maneuver violently (30° turns at 30 knots) to keep the after 5-inch mount bearing on these boats, and that, in turn, made life in the CIC uncomfortable. This battle lasted 17 minutes, during which time the ship fired 72 rounds. The USS Elmer Montgomery (FF-1082), steaming nearby, sank one of the small boats.

The Vincennes first detected Iran Air 655 two minutes before the surface action began, while the cruiser was being threatened. The Vincennes' CIC identified the contact as “unknown—assumed enemy.” This radar echo was identified with a Mode III IFF response, but the IFF operator also had a Mode II response at Bandar Abbas airport.7

The captain and his antiaircraft warfare (AAW) officer saw a vector, representing Iran Air 655, pointing at them and closing. They challenged it seven times, even though their ship was maneuvering during a gun action. The USS Sides (FFG-14) challenged the unknown air target five times. It never replied, nor did it maneuver evasively.8

In the CIC, the tactical information coordinator (TIC) sat at a digital (or character) read-out console. He later said that he had been concerned that, in concentrating on the hot surface action, the captain and his AAW coordinator would ignore the closing air target. He therefore called out the air target’s altitude (which he read as decreasing at 1,000 feet per mile) whenever he could, using command communications circuit 15, which the captain and AAW officer heard.9

The captain could wait only so long to take action. His Standard missiles could not intercept targets inside a substantial minimum range.10 Moreover, much depended on the nature of the threat. If it was a small missile, then it could be argued that a gun, such as the ship’s Phalanx CIWS, could probably deal with it, even if he failed to fire in time. (Note, however, that only one of the Vincennes's two Phalanxes was working, and that the only available 5-inch gun already was thoroughly occupied.) If, however, the captain was dealing with a possible suicide attack, then nothing short of a missile could protect his ship from serious, perhaps fatal, damage.

The AAW coordinator in the CIC asked to fire as soon as the unknown target came within 20 nautical miles. The captain waited as long as he thought he could. He authorized firing about seven minutes after the first detection of the air target, when it was ten nautical miles away. The Vincennes fired two missiles, and the airliner was hit at a range of about seven nautical miles, 17 seconds after the missiles left their rails.

Captain Rogers later reported that the key indicators that the unknown target was hostile had been its unwillingness to answer his challenges, its constant approach, and the apparent difference between its behavior and that of other commercial aircraft.11 Moreover, because of the error in IFF range-gating, the airplane had been identified tentatively as an F-14. Visual identification (for example, using a television camera) was impossible because the day was hazy, with a ceiling of only about 200 feet.

The most important consideration was the expectation that the Iranians would mount a major attack on the “Great Satan,” which they blamed for their misfortunes. All the pieces seemed to be present: the speedboats deployed to disrupt AAW cover; the targeting P-3; and the attacking F-14, which was clearly not transmitting so as to avoid alerting the target and which was flying along an airline corridor so that its intentions would be discovered only at the last possible moment. The potential for damage to the Vincennes was so great, given this context, that Captain Rogers had to react when he was told that the target was diving to attack.

In fact, the pieces did not fit together. The Airbus was climbing toward cruising altitude when the TIC said it was diving. The airliner’s weather radar was probably out of order. Its IFF transponder was working properly. Almost certainly the airport at Bandar Abbas was entirely unaware that the airliner was being sent over an ongoing surface battle, since the IRGC seems to have had little or no detailed instruction from the top. By this phase of the war, the Iranian command structure was badly disorganized.

Captain Rogers, therefore, took the only reasonable course of action, given the incomplete information available to him. It is important to emphasize that, even had he known that the approaching aircraft was an Airbus, he could not have been sure that it was not intending to attack him, since, like an F-14, it would have made an effective kamikaze. In this sense, the key evidence, which was quite reliably given, was the airliner’s refusal to veer off when warned. It is unknown, of course, whether the pilot understood the warning. (Reportedly the Iranian government instructed its airline pilots not to reply to such challenges. Because airline pilots varied in their responsiveness, emergency turns could bring an airliner almost onto a collision course with another, as actually happened to a British Airways flight after the attack on the Stark the previous year.)

As soon as the unknown target had been identified as a civilian airliner, the tapes of the Vincennes's Aegis data were analyzed. It turned out that the Airbus had indeed been climbing, a point that might have helped Captain Rogers decide not to shoot when he did. The conclusion seems to have been that the TIC, who was not experienced, had been reading the decreasing range figures as decreasing altitude, and that others in the CIC, expecting an attack, had accepted these data willingly. The TIC’s error was ascribed to the stress of a hot combat situation, and also to the human tendency to accept data that fit a preconceived picture. Air engagements move so quickly that no command system can be designed to check and recheck such data—which, after all, are supplied up the chain of command by trusted subordinates. One lesson learned, then, is that it would be useful to provide altitude data (or at least altitude trend data) directly on the large screen display that the captain and his AAW officer use for decision-making. Another is that the more graphic the presentation of data, the less chance that it will be misread (misinterpretation is a more difficult issue).

In a larger sense, there was not really much that could have been done to avert the destruction of Flight 655. The Iranians periodically made threats (for example, that the Great Satan would be sorry after the 4 July weekend) that they did not execute. But their threats had to be taken seriously, and thus had real consequences. The difference in style between the politico-military methods of some Third World nations and those of the advanced Western countries must inevitably cause serious problems.12

The loss of Iran Air 655, then, might be ascribed to the Iranians’ continued attacks on U. S. and friendly shipping in the Gulf, in that these attacks created an atmosphere in which it was much better for U. S. forces to shoot than to risk the consequences of not shooting. The consequences of the destruction of the Airbus were certainly profound. Iran almost immediately accepted the ceasefire that the United Nations had been trying to impose. It would be fatuous to imagine that the Airbus had been sent into danger in order to create a climate in which the cease-fire became acceptable for Iran. However, it might be reasonable to imagine that the Iranians’ attacks in the Gulf were intended to cause some incident that so demonstrated the power of their enemies (particularly of the United States) that it would be reasonable for them to accept peace, even after so many Iranians had been killed in the war. By shooting down the Airbus, therefore, the Great Satan showed its power and its ruthlessness. The Iranian government could see the incident as a demonstration that, although it had fought well against Iraq, the terms of the war had changed drastically, and thus that it was now compelled to make some kind of peace.

The answer to whether it will happen again is almost certainly yes, as long as the Third World continues to seethe and U. S. interests continue to demand a military presence. A future Captain Rogers would still have to fire based on incomplete data, and his CIC would still be trying to guess what lurked in the mind of the pilot of an approaching aircraft. The urgency of firing might be relaxed if ships (and their combat systems) were much more survivable, and if they had much more powerful, short-range defenses, but neither development is likely in the short term. Nor can it be hoped that officers on board ships will develop a miraculous resistance to the stress of combat. The Navy can do better; crews can use display systems better adapted to surveillance (for example, with better graphics for altitude). But the Navy and its crews on the front lines cannot really do that much better.

The main lesson, then, is that wars beget accidents, and that accidents—terrible accidents like—are unavoidable, however good the men involved.

1. Such filtering is essential if the system is to deal only with real data. It would, for example, reject some signals coming from distant targets that might appear through ducting, since those targets would seem, to the radar, to be moving unphysically. Ducting is common in the Persian Gulf, and on 3 July, the radar was functioning in both a surface duct (up to an altitude of about 485 feet) and in a surface evaporation duct (up to an altitude of about 78.5 feet). At least some radar signals are trapped in such ducts, which act like waveguides, and can travel far beyond the horizon. The ship receives echoes from distant targets (beyond its unambiguous radar range) as apparent echoes from much closer ones. Radars, such as SPY-1A, typically use special electronic techniques, such as a jittered pulse repetition frequency, to resolve such ambiguities. These points are complicated by the threat—particularly in the Middle East—of unconventional attack by, for example, slow civilian-type aircraft, which might normally be rejected altogether by the weapon system.

2. This is typical of modern radars, which provide processed video rather than the blips (“raw video”) of the past. Uninformed critics have suggested that if raw video had been supplied, the CIC could easily have distinguished the massive blip of an Airbus from the presumably much smaller one produced by an F-14. Some even imagined that modem radars provide, literally, pictures of the physical configuration of approaching aircraft. In fact, the shape of a raw video blip is a poor indicator of target size and shape, particularly when the target may have features, such as the large antenna of the F-I4’s AWG-9, that greatly increases its radar cross section. Imaging radar has been suggested as a means of noncooperative identification, to circumvent the obvious limitations of IFF, but it has not been implemented in any existing system; nor is it clear that it can be implemented in a long-range search radar such as the SPY-1A.

3. There is a brief allusion to such a possibility in one of the endorsements to the official report, but it is not clear whether a suicide attack by a large modem aircraft is meant. Given the lack of spares (because of the U. S. arms embargo), though, it would be reasonable to suspect that aircraft like Iran’s F-14s were becoming increasingly difficult to maintain, and therefore would have become expendable.

4. It was widely reported after the Falklands Conflict that the Argentine Super Etendard that attacked and hit HMS Sheffield had been coached into place by a patrol aircraft, a P-2 Neptune equipped with a surface search radar. The P-3 Orion is the lineal descendant of the P-2, and has a similar surface search capability. Of course, its use of this capability would not show that any particular attack was occurring.

5. Phalanx has an inherent capability to be wired so that it can engage such targets in local control, but the Navy disapproved the modification involved, presumably to keep the guns always available for antimissile defense.

6. Because the Mk-45 gun mount is entirely unmanned, a round that has not fired. Properly can be removed only by opening the gunhouse, something that is almost impossible during combat. The mount was designed with unmanned operation in mind (that is why it fires relatively slowly) and is usually quite reliable.

7. The operator did not move his range gate with the target, and therefore misidentified the Mode II IFF response with this target. Movement of the IFF range gate is semiautomatic. In a conventional mechanically scanned radar, the IFF interrogator automatically points at the radar’s target, and thus it is much more difficult to make this kind of error. Electronic scanning (as in the SPY-1A) has so many advantages over mechanical scanning, particularly when high-speed targets are involved, that this IFF advantage would seem minor at best.

8. It would later be pointed out that, after the Stark incident, the U. S. government had issued a general warning (Notice to Airmen) to the effect that U. S. ships in the Gulf would fire to protect themselves against aircraft that seemed to be flying threatening courses. The notice specified the radio channels on which warnings would be sent. Tapes of the Vincennes's radio communications show that the messages sent to Iran Air 655 read as follows: “Unidentified Iranian aircraft on course 203, speed 303, altitude 4,000, this is U. S. naval warship, bearing 205, 40 miles from you. You are approaching U. S. naval warship operating in international waters. Request you state your intentions.’’ A later warning added, “You are standing into danger and may be subject to USN defensive measures. Request you alter course immediately to 270.’’

9. The TIC was misreading his instrument, and presumably he was under stress because he believed he was under attack. In the CIC of the nearby frigate Sides, which was clearly not under attack, evaluation was cooler, and at least some personnel in her CIC tentatively identified the unknown track as an airliner. That inclusion was probably made partly because Sides's IFF, physically attached to her SPS-49 radar, correctly read the civilian (Mode III) signals emitted by the target. Sides was tracking the target in altitude, probably using its Mk-92 fire control radar (Mk-49 is two-dimensional, only). The Sides's captain later recalled evaluating the track as nonthreatening based on its calculated closest point of approach (to his ship), its lack of detected radar emissions (which on board the Vincennes could be interpreted as control by a targeting aircraft), the lack of previous experience of F-14 antiship attacks, and on precedent. Sides was far enough from the Vincennes not to be involved in the surface action. Subsequent evaluation of the Vincennes's tapes showed that the TIC was sufficiently insistent on his altitude data that all personnel in the CIC accepted it, even though the radar itself was receiving different data.

10. This situation is typical of air-defense missiles. They must accelerate to a sufficient speed for enough air to flow over their control surfaces. That is why guns are generally used for short-range defense.

11. Although within the corridor (and corridors cover about half the Gulf), Flight 655 was not keeping rigidly to the centerline, as airliners tend to do. It was reported—incorrectly—to be diving and accelerating. Its reported altitude was lower than that of most commercial flights, and its flight pattern did not seem to match those of commercial flights. The Vincennes's CIC also noted that the ship’s SLQ-32 intercept receiver did not pick up the characteristic signals of an airliner weather radar.

12. The destruction of Pan Am Flight 103 in December 1988 may be a case in point. It turned out that the U. S. embassy in Helsinki had received a vaguely worded threat, which had actually run out some days before the Pan Am airliner was bombed. Relatives of the victims of the bombing were furious that this threat had not been published. They were told that such threats are common (at least one is received daily) and therefore that publication is pointless; all would soon be disregarded, since most prove false.

13. A parallel might be seen in the nuclear attacks that ended the Pacific War. The Japanese government had sacrificed so many of its citizens that it could not easily admit defeat. However, it could have defeat with honor if defeat were enforced by weapons so terrible as to be supernatural. It could be speculated that the current Japanese attitude toward nuclear weapons is based, perhaps unconsciously, on the view that Japan could be defeated in war only by something beyond the pale of normal warfare. Certainly the Ayatollah Ruhollah Khomeini’s speec