In 1950, a U. S. submarine was in Miami on a “leave and recreation” visit. A short distance down the waterfront lay a small white freighter unloading bananas. A young officer from the submarine casually watched as the stevedores passed stem after stem down a conveyor belt to an inspector who graded each bunch and shunted it along to the proper basket. Soon, however, the officer’s eye turned toward the ship herself. Rust streaks peeled down from rivets and hawsepipe, and the thick layers of paint which adhered in patches to the dented hull attested to the vessel’s advanced age. Her only superstructure consisted of two low, wooden deckhouses, one amidships and the other at the very stern. Big cowl ventilators were spaced along the deck. But what struck the observer as out of the ordinary was a peculiar straightness of the hull lines. From a sharp, straight bow, the weather deck ran in almost a flat line all the way to the fantail. A closer look revealed an extremely narrow beam and a fineness of shape at the extremities that naval architects never use in designing ordinary merchant ships.

The hull was obviously that of a former naval vessel, and a destroyer at that. Furthermore, she could only be one of the flush-deck destroyer class constructed for the U. S. Navy in the crash program of World War I, when the German U-boat campaign threatened to bring England to her knees. The distinctive straight deck was unlike that of any destroyers built before or since, and most of the 273 members of the class bore four tall, straight stacks. Hence they had been known throughout the service for over a quarter-century as “flush-deckers,” or more popularly, as “four-pipers.”

No four-pipers had served in the U. S. Navy since 1946, but even before World War II, the old destroyers had been regarded as obsolescent. Many had been scrapped as worn-out as far back as the 1930s. Fifty more were traded to Great Britain in President F. D. Roosevelt’s famous “destroyers for bases” swap in 1940. Another, the Reuben James, (DD-245), was the first U. S. naval vessel sunk by a Nazi submarine in World War II. Still another, the Ward (DD-139), drew first blood against the Japanese by sinking a midget submarine off the entrance to Pearl Harbor only minutes before the fateful attack on that great naval base plunged the United States into the holocaust of war.

Yes, the four-pipers had seen their day of fame, but they were already fading into the oblivion of nautical history. Where, then, had this banana boat come from?

Among seamen, ships are known to have personalities of their own which persist despite changes in captains and the rotation of crews. Somehow, these cold steel hulls seem to possess a life and vitality that impels nautical writers to describe them in anthropomorphic terms. The ship did this or that, they tend to write, knowing full well it was really the crew who lighted off the boilers, hoisted anchor, steered the course, and manned the guns. Crews, for the most part, are anonymous and transient, while the life of the ship can be counted from the day she is launched until she is finally sunk or broken up.

So it was with this banana boat, whose name was Teapa. This was not her destroyer name, of course, only that which had been given her when she entered the banana trade. In the Navy she was the USS Putnam (DD-287). Built in 1919 at the Bethlehem Ship Building Corporation yard in Squantum, Massachusetts, the Putnam and her sisters Worden (DD-288), Dale (DD-290), and Osborne (DD-295) had served with the active fleet until 1930, when the prospective expense of refitting worn-out boilers led the Navy to replace 60 of the four-pipers with others from the reserve fleet. Practically all of those retired were sold to the shipbreakers, and their scrap steel went, as likely as not, to the gulping mills of Japan. These four, however, were stripped down to bare hulls, sold to the Standard Fruit Company, given economical diesel engines in place of their original 26,000-h.p. steam turbines, and converted to banana carriers.

In general, a warship makes about the worst freighter one can imagine, and destroyers are probably more ill-fitted for merchant service than anything except a submarine. Their hulls are shaped for extreme speed, not capacity. Their bulkheads are designed to resist flooding, not to facilitate the stowage of cargo, and their entire mode of construction is uneconomical by commercial standards. For the banana trade in the 1920s and 1930s, however, there was a logical rationale for this use of destroyer hulls. They were big enough to carry a cargo of 25,000 stems of fruit and small enough to be operated by a crew of 19. (As warships they had carried upwards of 120 men.) Their fine hull lines permitted a speed of 16 knots even with a small, inexpensive diesel plant, and their shallow draft was suitable for navigating up Central American rivers, thus saving on rail transportation. Their speed was just enough to dispense with artificial refrigeration. Instead, a flow of air was forced into the holds through the big ventilators, and the combination worked out just right for the run from one of the Caribbean banana ports to New Orleans, Norfolk, or Miami. The fruit, when it was unloaded, had ripened just enough to make it ready for shipment to the retail market.

So the Standard Fruit Company knew exactly what it was doing when it converted four worn-out destroyers to banana boats. The Worden became the Tabasco, the Dale was renamed Masaya, and the Osborne was rechristened Matagalpa. Year after year the four quietly hauled their bananas. Although they tended to roll heavily at sea, they made good speed and were always on schedule. In 1933, the Tabasco piled up on a reef in the Gulf of Mexico, but the other three continued to toil away in obscurity until World War II.

Few people who lived through the days of 1941 and 1942 will ever forget the atmosphere of desperation that prevailed when it appeared that we were losing the war on all fronts. While German U-boats sank tankers up and down the Atlantic coast, our forces in the Pacific were mobilizing every rust bucket afloat in what seemed to be a futile effort to stop the Japanese advance through the Southwest Pacific. In the Philippines, General Douglas MacArthur’s troops inched backward down the Bataan peninsula. As supply lines from Australia and the Netherlands Indies were severed one by one, MacArthur pleaded that aid be sent at any cost, by blockade runners direct from the United States if necessary. Shipping rosters were scoured for suitable craft, and soon the ignominious Standard Fruit banana boats were the subject of intense scrutiny by General George C. Marshall and President Franklin Roosevelt himself. The Army had requisitioned the three survivors for its Transportation Corps, and Major General Brehon Somervell, Assistant Chief of Staff, G-4, reported that they would make ideal blockade runners.

Taken over as Army transports on bareboat charter, hurriedly furnished with Army gun crews and a motley array of armament, they were loaded with supplies of the highest priority under conditions of stringent secrecy. The first to leave, the Masaya, (ex-Dale), departed New Orleans on 3 March 1942, with a cargo of ammunition, avgas, medical supplies, and mail. The Matagalpa, (ex-Osborne), followed with a load of rifles, machine guns, mortars, anti-tank mines, ammunition, serum, and cigarettes. The Teapa, (ex-Putnam), was last, with a nearly identical cargo. Slowly they made their way through the Panama Canal and up the Pacific coast to San Pedro, California. Engine repairs and restowage of cargo wasted precious days, and the defenders of Bataan were forced to surrender before the ships were ready to sail. By the time the ships reached Honolulu, the situation of the few American forces remaining in the Philippines was hopeless.

The Masaya was diverted from the Philippines to Australia where she was remanned with an Aussie crew as an interisland transport for MacArthur’s forces. On 28 March 1943, she was jumped by five Japanese dive bombers and sunk at Oro Bay, New Guinea, with the loss of two lives.

The Matagalpa, too, was ordered to the Southwest Pacific, but soon after arriving at Sydney, Australia, she was gutted by fire in her berth on 27 June 1942, and was subsequently scrapped.

Thus, only the Teapa survived the war. After being held in Honolulu for repairs, she was returned to Seattle, Washington, to join the Alaska run. Departing from Puget Sound with a cargo of beans, sugar, canned pineapple, cornstarch, and U. S. mail, she lay off Seward, Alaska, waiting for pier space to become available. On 28 November 1942, while at anchor in Thumb Cove, Resurrection Bay, fire, caused by oil from a leaking donkey boiler, broke out in Number 3 hold. When the flames were finally extinguished by Army and Navy firefighting teams from Seward, her decks and wiring were found to be severely damaged. In fact, the deck plates and frames were reported to be so badly corroded that patches could not be welded on safely. Since the ship was obviously in no shape for further service on the rough Alaska freight route, it was decided to refit her for limited use as a training ship for instructing Army, Navy, and Merchant Marine men in engine operation and anti-aircraft gun practice. This useful, if unheroic, duty was carried out faithfully and well, and the end of the war found the Teapa still serving in this humble capacity at Seattle.

With demobilization, the ship was returned to her former owners and, in 1947, came into the hands of the McCormack Shipping Corporation. Although almost 30 years of age and practically worn out from strenuous service, the Teapa went back to sea, carrying bananas from the Dominican Republic to Miami until 1950, when she was finally laid up. She was ultimately sold for scrap in 1955.

The records of the Army Transportation Corps contained a cryptic mention of three other former destroyers that were also being sought as Philippine blockade runners, but there was no hint as to their names or particulars. A search through the records of the flush-deckers discarded by the Navy prior to World War II disclosed no likely candidates, and it looked like a case of mistaken identity until an earlier chapter in the banana boat saga came to light.

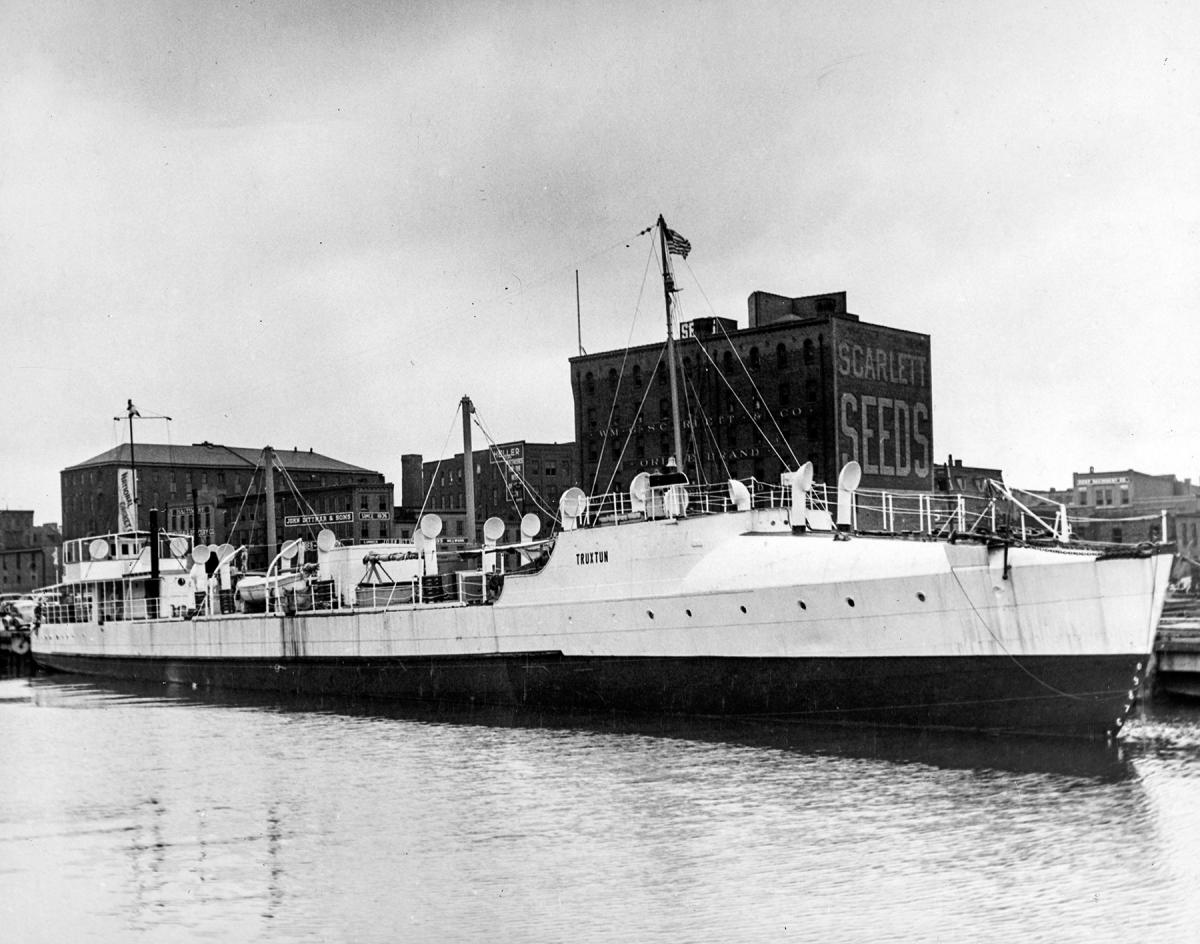

Shortly after World War I the Navy got rid of its earliest classes of destroyers, and three of these were bought by private shipping interests for the first experiment in making small, fast, shallow draft banana carriers. By an extraordinary coincidence, one of these, the old DD-16, was also named Worden. Her sisters were the Truxtun (DD-14) and the Whipple (DD-15). Refitted with economical diesel engines, these three operated under the Nicaraguan flag but carried their original destroyer names. The Worden was listed as having two 6-cylinder Wolverine oil engines delivering 400 b.h.p., while her sister ships carried Atlas diesels. The three conversions must have been successful enough to stimulate the later alteration of the four flush-deckers, but the ships passed through a succession of owners, such as the Snyder Banana Company, Southern Banana Company, and American Fruit and Steamship Company. Although they were never pressed into service as blockade runners, they outlived their newer counterparts in the banana trade. They last appeared in Lloyd’s Register for 1955–56 under the ownership of the Bahama Shipping Company, Ltd.

The fact that these old hulls, built with thin plates and lightweight frames, stayed in use for more than 50 years is testimony to the quality of materials and workmanship that went into the Navy’s first destroyers. The photograph of the Truxtun shows her original turtle-back forecastle, billboard, and old-fashioned anchor. This type of round, sloping bow was eventually abandoned by the Navy because it was too wet in a seaway. The round conning tower and plated-in gun platforms under the bridge are also clearly visible in the picture. Hardly a dimple can be seen in the sturdy little hull.

There probably will never be another destroyer converted into a banana boat to challenge the title of these ships as the most unlikely examples of beating swords into plowshares that human ingenuity could devise.