By April, 1942, the Japanese Navy had accomplished all of its missions originally scheduled for the opening phase of the Pacific War. Since December 7, 1941, it had severely crippled the United States fleet in Hawaii, supported landings, invasions, and seizures of southern areas rich in resources sorely needed by Japan, and had gained control of the sea lanes of the central and western Pacific. And all of these objectives were achieved at far less cost than had been anticipated.

Japanese staff studies for the planning of second-phase operations were initiated as early as January, 1942. By February plans had been worked out and developed between Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters in Tokyo and Combined Fleet. Members of both staffs were so enthusiastic over the early successes that they were now firmly in favor of going ahead with plans for further conquest, before the United States had a chance to recover.

In March the staff of Combined Fleet proposed the capture of Midway in order to secure a foothold in the mid-Pacific and to bring about the greatly desired decisive battle with the U. S. Fleet. They insisted that Midway should be captured and fortified before the wounds indicted at Pearl Harbor had time to heal. It would be a stroke of especially good luck for Combined Fleet, they believed, if a chance arose to engage the Americans in a decisive surface fleet action in connection with the Midway operation. Initially that entire undertaking was opposed by Navy Section of Imperial General Headquarters for two reasons: (1) the difficulties involved in supplying such a distant base after it had been seized; and (2) the impossibility of bringing up reinforcements in the event of a sudden enemy attack. The two staffs were pitted against each other at a joint conference held in Tokyo on April 2 5. Under strong pressure from Combined Fleet, Admiral Osami Nagano, Chief of the Naval General Staff, finally yielded, and the tentative plan to attack Midway was formally approved.

The plan for second-phase operations was accordingly revised by Imperial Navy Directive No. 86 on April 16. The occupation of Port Moresby was set for early in May, of Midway and the Aleutians for June, and of Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia for July. In the spring of 1942 the cherry blossoms, at their fullest bloom, seemed like a symbol of continuing victory for the Japanese Navy; but Japan’s wind of misfortune was making up and would soon begin to blow.

On April 18 came the Halsey-Doolittle raid on Tokyo. The Battle of the Coral Sea in May shattered Japan’s sea road to Port Moresby. A month later in the Battle of Midway the Imperial Navy suffered its most bitter defeat. At Midway four first-line aircraft carriers of Combined Fleet were lost at one blow, and with them went the Fleet’s mobility and strength.1 On June 11 as a result of these reverses, the Fiji-Samoa-New Caledonia operations scheduled for July were postponed and later cancelled.

It had been planned to activate the Eighth Fleet as a local defense force for Fiji, Samoa, and New Caledonia after the occupation of those islands. The cancellation of these operations was a personal disappointment to me. As a prospective staff member of Eighth Fleet, I had been studying and preparing for the exploitation of advantages that would accrue to Japan. One bright goal was the nickel and chrome mines of New Caledonia. Another was the chance to use Noumea as a submarine base from which to conduct raids against the lines of communication between the United States and Australia.

Since the balance of naval power in the Pacific inclined toward the United States after Midway, the Japanese concluded that the southeast Pacific offered the most probable arena for a decisive naval action. The Eighth Fleet was activated July 14, under command of Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa, with the assignment of defending the area south of the equator and east of 141° east longitude. The operational designation was the “Outer South Seas Force.”

Admiral Mikawa had been second in command to Vice Admiral Nagumo of the Pearl Harbor Striking Force, in which he himself had the Support Force, consisting of Battleship Division 3 (Hiei, Kirishima) and Cruiser Division-8 (Tone, Chitose). In this command he continued to support the carrier task force as it proceeded with raids on Lae, Salamaua, and Ceylon. Following the Battle of Midway his command of Batdiv 3 passed to Vice Admiral Takeo Kurita on July 12, and two days later Mikawa was placed in command of the Eighth Fleet. A gentle, soft-spoken man and an intelligent naval officer of broad experience, Admiral Mikawa was recognized for his judgment and courage.

On the very day of his appointment to command of the Eighth Fleet I visited Admiral Mikawa at his modest home in Setagaya, an outlying ward of Tokyo. His first job for me was to “go out to the forward areas for a first-hand look at the war situation and survey local conditions at our bases.” I left Yokohama by flying boat in the early morning of July 16, staged through Saipan, and flew on to Truk. This base was the headquarters for Vice Admiral Shigeyoshi Inoue’s Fourth Fleet, which was then responsible for operations in the Outer South Seas, or Southeast Pacific area.

Fourth Fleet staff members outlined to me the following operational plans:

- The seizure of Port Moresby was to be carried out, this time by overland operation starting from Buna. The Nankai Detachment, as the first echelon, was scheduled to leave Rabaul on the 20th and land at Buna the following night. Additional forces would come after this initial contingent which was to follow the Kokoda trail through and over the Owen Stanley mountains to Port Moresby. The Buna landing and its follow-up operations were considered to be the most urgently important of Fourth Fleet’s present plans.

- As a result of lessons learned from the Coral Sea and Midway battles, efforts were being made to establish and strengthen air bases in the Solomons and Eastern New Guinea. A survey conducted in cooperation with the Eleventh Air Fleet had shown, that there were favorable sites for an airfield at Buna, in Papua, and near Lunga Point on Guadalcanal, in the southern Solomons. Construction had been started on a landing field and a nearby dummy strip at Guadalcanal. But no suitable location for an airfield had yet been found in the central Solomons.

- It was conceived that, after the occupation of Port Moresby, our air garrison there should be limited to fighter planes. Bombers would be sent there only as needed and, after their mission, would return to Rabaul to avoid the risk of losing them on the ground.

I asked for an estimate of the area situation and the enemy’s capabilities. On these points Fourth Fleet judged that:

- For the time being, the United States was incapable of effecting large-scale counterattacks.

- The U. S. carrier task force attack on February 20-21 on Rabaul had been successfully repulsed. There were no indications that a similar effort was being planned. There was little probability of such attacks in the near future.

- We had a seaplane unit deployed at Tulagi which had been there since early July. It was necessary to establish a land-based air garrison at Guadalcanal as soon as the airfield was ready, but Eleventh Air Fleet saw difficulties in accomplishing this because of a scarcity of reserve planes.

Upon completion of these studies, I left Truk by flying boat at 0700 on the 20th and arrived at Maruki seaplane base in Simpson Harbor, Rabaul, shortly after noon. White smoke drifted lazily from the mouth of the nearby active volcano. At the pier was a half-submerged merchant ship, her red hulk a striking contrast to the sparkling blue sea. Transports and small naval vessels anchored in close order along the beach offered easy targets in the event of an enemy air raid. Upon landing I expressed this thought and was surprised at the lack of concern shown by the commander of the local defense.

This area’s defense was the responsibility of the 8th Base Force. Air operations were under the direction of the 25th Air Flotilla, which was a part of the Eleventh Air Fleet. But Eleventh Air Fleet headquarters and its commander in chief were located at Tinian, in the Marianas. Although the 8th Base Force and 25th Air Flotilla were supposed to be acting in close cooperation, it was soon apparent to me that the local atmosphere was anything but cooperative. Observing this situation, I could understand the rumored ill feelings that had sprung up at the Battle of the Coral Sea between the carrier task force and the air forces based at Rabaul.

In conversation with staff officers of the 8th Base Force, the situation in the Solomons was presented to me as follows:

- On May 2, Tulagi and Gavutu had been occupied by the Maruyama Company of the Kure 3rd Special Naval Landing Force (about 200 men) and an antiaircraft detachment of about fifty men from the 3rd Base Force. Starting on May 4 some 400 men—the Marumura and Yoshimoto Companies—of the Kure 3rd Special Naval Landing Force conducted mopping up operations in key areas of Savo, Florida, and Santa Isabel Islands, after which they rejoined the main body at Kavieng.

- On June 8, a section of the Tulagi garrison occupied the Lunga area of Guadalcanal. Eleven days later, an airfield survey group headed by officers from 11th Air Fleet and 4th Fleet was sent to Guadalcanal. As a result of this survey an airfield site was chosen, and 1,221 men of the 13th Construction Unit (Lieutenant Commander T. Okamura) were brought in. They were joined on the 6th by 1,350 men of the 11th Construction Unit (Captain K. Monzen), and within ten days work had begun on an airfield. There were occasional small-scale air attacks by the enemy, but these inflicted little damage and did not interfere with the construction of the airfield.

- The 84th Garrison Unit (Lieutenant Commander Masaki Suzuki), reinforced by the 1st Company of the 81st Garrison Unit, was organized locally to defend the area, pending the establishment of the air base at Guadalcanal. The total strength of this force was about 400 men.

- After the occupation of Tulagi, some 400 officers and men—roughly two thirds of the strength of the Yokohama Air Group—commanded by Captain Miyazaki, proceeded to Tulagi. A detachment of 144 men from the 14th Construction Unit under Lieutenant Iida had been working on the Tulagi seaplane base since July 8.

- The general situation in the Solomons was quiet. Efforts were being made, by aerial reconnaissance, to find a suitable airfield site somewhere between Rabaul and Guadalcanal, so far without success. But since early July the main part of the 14th Construction Unit had been improving an emergency airfield at Buka which would be adequate for medium bombers. When the bases at Guadalcanal and Buka were finished, the air defense of the Solomons would be complete.

Thereafter the conversation changed to problems involved in the Port Moresby operation. I had the distinct feeling from these talks that a new higher command organization at Rabaul would be most unwelcome. It was clear to me that the present command felt that everything was going quite well. In fact, they showed their really negative attitude when it came to a discussion of housing for the headquarters of Eighth Fleet. It was pointed out to me that there were no adequate accommodations on shore—although the present commands were certainly housed in comfortable quarters—and that any surface force commander would certainly prefer to keep his headquarters afloat in his flagship in order to cope with possible emergencies.

It so happened that Admiral Mikawa had informed me in advance concerning his wishes about the stationing of his ships. He was well aware of the fact that it would be unfavorable to have a division of heavy cruisers stationed where they would be exposed to enemy attack. He had determined that his ships should train in the safer rear areas such as Kavieng, Truk, or the Admiralties; but that local operations should be commanded from ashore at Rabaul. If the need arose, Admiral Mikawa could always move his headquarters to a ship and take command afloat. Accordingly, I requested that preparations be made ashore for the Fleet headquarters, and this was done, but the accommodations offered were far inferior to those of the lesser headquarters of the 8th Base Force.

I next paid my respects to the commander of the 25th Air Flotilla and discussed the local situation with his staff. By early August the airfield at Guadalcanal would be completed, they informed me, and ready to accommodate about sixty planes, and by the end of the month it would be able to handle the entire flotilla. They also raised the doubt, as had Eleventh Air Fleet, that there would be sufficient reserve strength to divert an effective number of planes to Guadalcanal. It was my feeling that the 25th Air Flotilla people were not really concerned about obtaining planes for the new base. The reason for their lack of interest arose from the fact that the 25th Air Flotilla, which had long been engaged in the strenuous air battle against Port Moresby, was soon to be relieved by the 26th Air Flotilla. Upon being relieved, the 25th would withdraw to a rear area for refitting and replenishment, and thus be free from local responsibilities.

It was plain that the fighting spirit of the base force and of the air flotilla was sorely tried, but this was understandable, since they had both been involved in drawn-out, monotonous operations. After two days at Rabaul, I returned to Truk, where, on July 23, Lieutenant General H. Hyakutake arrived with his 17th Army Headquarters. I was invited to a dinner in their honor given by the Fourth Fleet Commander, Admiral Inoue. At this gathering I learned that the interests and energies of 17th Army were to be devoted entirely to the Port Moresby invasion operations and that they had absolutely no concern with the Solomons. This information made me skeptical of the wisdom of the Central Army-Navy agreement which had placed responsibility for the defense of the Solomons upon the Navy alone.

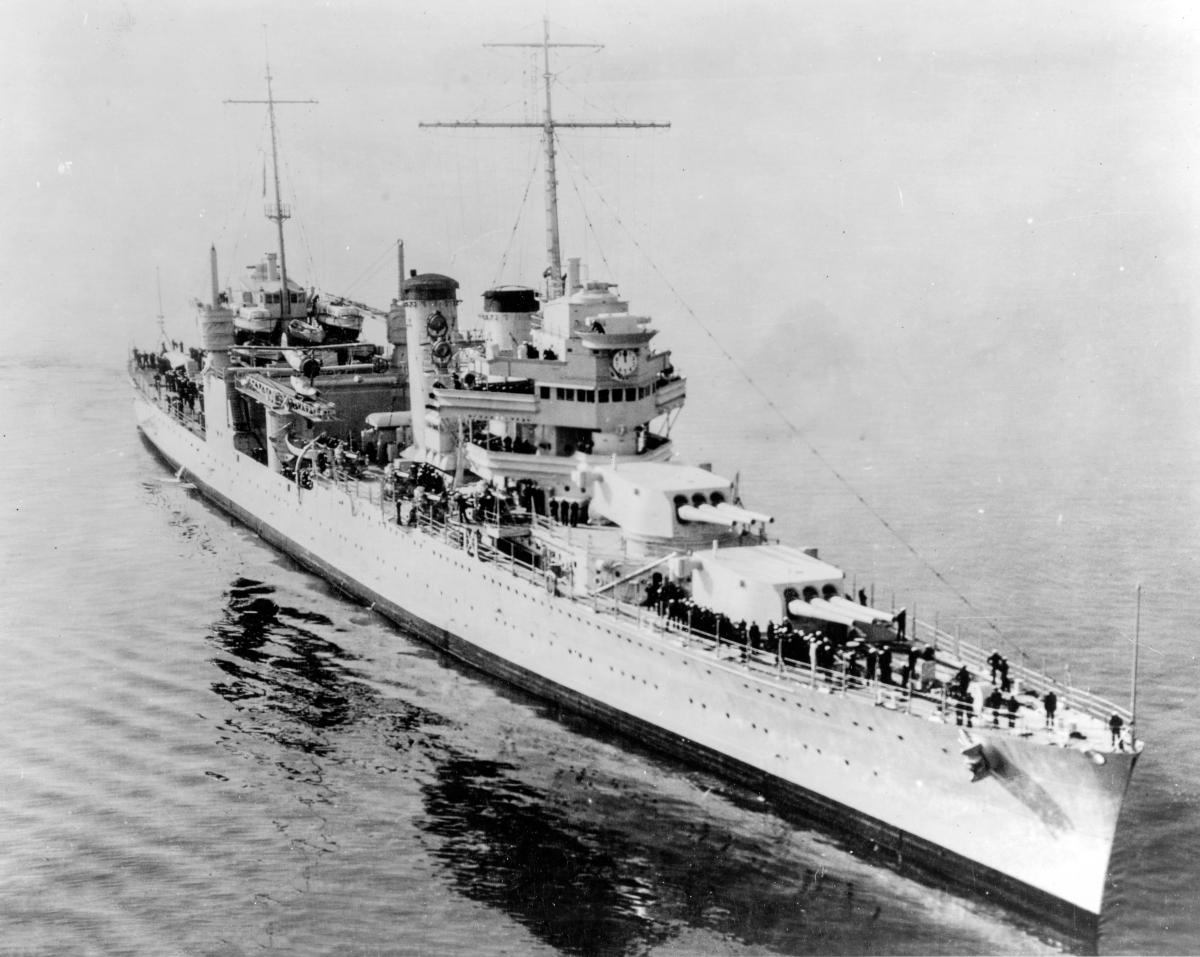

Eighth Fleet flagship, heavy cruiser Chokai escorted by Destroyer Division 9, entered Truk harbor on July 25 and dropped anchor at noon. I reported to Admiral Mikawa at once, giving him a full account of what I had learned in the past eleven days. There was a conference this same day between the staffs of Eighth and Fourth Fleets. Mikawa’s staff expressed concern at the possibility of a large-scale enemy attack against the Solomons or the eastern part of Papua. This concern was dismissed by Fourth Fleet staff as the mere anxiety of a newcomer. Eighth Fleet assumed command of the Outer South Seas Forces at midnight on July 26, and flagship Chokai sailed for Rabaul at 1500 the next day. It was a revival for me, after five year’s absence from sea duty, to be underway in this fine cruiser. It brought back memories of the battle of Woosung Landing by the 3rd Army Division, five years before, when I had commanded the lead destroyer.

At 1000 on July 30 we entered Simpson Harbor, Rabaul. Vice Admiral Mikawa moved ashore that same day, and his flag was raised above a ramshackle building near the 2nd Air Group billet. The modest, indeed humble, quarters lacked even toilet facilities, but Admiral Mikawa was not discouraged. And he stood by his decision to hold the cruisers in the rear area at Kavieng.

In a planning room borrowed from 8th Base Force, we conferred on the last day of July with 17th Army regarding the Port Moresby operation. The advance contingent of the Nankai Detachment had already occupied Kokoda and was continuing its trans-montane advance. The need was urgent for opening a coastal transport route to Port Moresby, because it would be impossible to bring daily supplies, let alone heavy weapons, through the Owen Stanley range. We made plans for a sea-borne invasion of Port Moresby by mid-August, after Samarai and Rabi, in Milne Bay, had been occupied. Meanwhile the Eighth Fleet was fully engaged in transporting 17th Army troops to Buna, and, by local Army-Navy agreement, preparations were under way for the invasion of Rabi.

At this time a steady stream of messages was coming from Lieutenant T. Okamura, commanding officer of the construction unit at Guadalcanal, requesting planes for that base. But Eleventh Air Base headquarters gave no sign of complying with this request. Enemy air attacks on Guadalcanal were increasing steadily. Single-plane raids every second or third day against Tulagi and Guadalcanal were giving way to almost daily raids by several enemy planes. There were seven B-17s on the last day of July, ten on August 1, eleven on the 2nd, two on the 3rd, nine on the 4th, and on the 5th five planes attacked. Imperial General Headquarters Special Duty Group (Radio Intelligence) sent a dispatch on August 5 suggesting the possibility of active enemy operations in the South Seas Area, based on an increase in communications activity. Eighth Fleet digested this information and concluded that the focus of this enemy endeavor would be in Papua, where the Owen Stanley thrust by our Army troops was making rapid advance along the Kokoda trail toward Port Moresby. It was logical that the enemy would move a carrier task force to disrupt our supply line to Buna. In addition to raids on Buna, it was likely that the enemy would repeat his carrier-borne attacks of March 10 on Lae and Salamaua. We concluded that the air raids on Guadalcanal must be diversionary.

On July 31 a convoy consisting of minelayer Tsugaru, transport Nankai Maru, and subchaser PC-28 was attacked by enemy planes and forced to abandon its plans to enter the anchorage at Buna. We believed that the enemy would bend every effort to intercept our next big convoy to Buna, scheduled to arrive there on August 8. This convoy, which carried the main body of the Nankai Detachment, consisted of three transports, Nankai Maru, Kinai Maru, and Kenyo Maru, escorted by the light cruiser Tatsuta, the destroyers Uzuki and Yuzuki, and by PC-23 and PC-30. Eighth Fleet’s principal mission at this point was the seizure of Port Moresby. It was planned, therefore, to stage an all-out air attack against Rabi in the early morning of August 7, because we were aware that the enemy had recently been building up the air base there.

On August 6 a message from Guadalcanal informed us that natives helping our construction forces to build the airfield had suddenly fled into the jungle the previous night. This provoked no concern at headquarters, since native laborers had been known to abandon work unexpectedly and without apparent reason. Our search planes reported no enemy activity south of Guadalcanal on the 6th, and the day passed without incident.

The calm of the following dawn was shattered with the arrival of an urgent dispatch at headquarters: “0430. Tulagi being heavily bombarded from air and sea. Enemy carrier task force sighted.” It was quickly evident that the strength of the enemy force was overwhelming, as successive messages indicated: “One battleship . . . two carriers . . . three cruisers . . . fifteen destroyers . . . and thirty to forty transports.”2 And by the time that the Eighth Fleet staff had been. aroused from sleep and had assembled at headquarters, the situation looked most discouraging. It appeared next that the enemy was effecting landings simultaneously at Tulagi and on Guadalcanal.

Contact with the forces on Guadalcanal was broken after a last word that they had “encountered American landing forces and are retreating into the jungle hills.” The last news from our base at Gavutu was that our large flying boats were being burned to prevent their falling into enemy hands. And at 0605 came a fateful message from the Tulagi Garrison Unit: “The enemy force is overwhelming. We will defend our positions to the death.”

It was plain that our forces of about 280 riflemen on Guadalcanal, and only some 180 at Tulagi, were no match for the enemy’s well-equipped amphibious troops. The situation was serious.

We did not know at first whether this was a full-scale enemy invasion or merely a reconnaissance in force. But, as the picture became clear of the size of the enemy forces involved, we were soon forced to recognize the enemy’s intention to stay and seize these islands. With this awareness, it was immediately apparent how serious it would be for our position if the enemy succeeded in taking Guadalcanal with its nearly-completed airfield. A plan of action was hastily worked out.

All available planes of the 25th Air Flotilla, which stood ready for the morning’s intended raid on Rabi, were at once diverted to attack Guadalcanal. A surface force of all available warships would proceed to the enemy anchorage at Guadalcanal and destroy the enemy fleet in night combat. At the same time it was decided that ground reinforcements would be moved to Guadalcanal, to land immediately after the fleet engagement, and drive off the invading enemy. All available submarines (there was a total of five, belonging to Submarine Squadron 7) were, of course, ordered to concentrate around Guadalcanal to attack American ships and keep in contact there with lookout posts. At 0800 Admiral Mikawa ordered all the heavy cruisers still in the Kavieng area to make best speed to Rabaul, thence to carry out an offensive penetration of the enemy forces at Guadalcanal.

The deployment of Japanese naval forces within the area of the command of Eighth Fleet on August 7, 1942 was as follows:

Planes

Vunakanau: 32 “Bettys”

Lakunai: 34 “Zekes”, 16 “Vals”, 1 Type-98 recco.

Maruki seaplane base: 5 “Mavises”

Warships

Kavieng: CA Chokai, Crudiv 6 (Aoba, Kinugasa, Kako, Furutaka)

Rabaul: CL Tenryu, Yubari, DD Yunagi

There were, in addition to these, the three destroyers (Tatsuta, Uzuki, Yuzuki) engaged in escort of the Buna convoy. Submarine RO-33 was on lookout station off Port Moresby, and RO-34 was conducting a commerce-raiding mission off Townsville, Australia.

In planning this operation our most serious problem was how to deal with the American carriers, of which it was estimated that there were at least two—and possibly three. It had to be expected that the enemy would launch at least one carrier-based air attack against our assaulting ships. It would be ideal if the planes of the 25th Air Flotilla could eliminate the enemy carrier threat, but complete destruction of these mighty ships solely by air attack could not fairly be expected. If, somehow, a thrust from the enemy carriers could be avoided, we felt assured of reasonable success against the other enemy ships because we had complete confidence in our night battle capabilities. The time set for our penetration of the Guadalcanal anchorage was midnight.

Another vital element was the landing of infantry reinforcements for our small force on Guadalcanal. This had to be done speedily, before the enemy could establish a firm foothold on the island. In conference, the 17th Army staff was confident that it would not be difficult to drive out whatever meager American forces might be delivered to Guadalcanal. In this judgment they sadly underestimated the capability of the enemy.3 They also said that a decision for immediate diversion of the Nankai Detachment to Guadalcanal could not be made at 17th Army level —which meant that no Army forces were available to reinforce the island. Consequently, Eighth Fleet hastily organized a reinforcement unit of 310 riflemen with several machine guns, and 100 men of the 5th Sasebo Special Naval Landing Force and 81st Garrison Unit, then at Rabaul. It was arranged for this small force, commanded by Lieutenant Endo, to board 5,600-ton Miyo Maru and head for Guadalcanal under escort of supply vessel Soya and minelayer Tsugaru. As details were being worked out, Chokai was ordered into Rabaul to embark Admiral Mikawa’s staff while Crudiv 6 headed for the rendezvous point in St. George Channel.

In the flurry of excitement at headquarters we were startled at 1030 by the sound of three shots of gunfire—the air-raid alert. Enemy daylight air attacks were a novelty at this time, and all of us at headquarters rushed outside to see what was happening. There were thirteen American B-17s flying eastward at about 7,000 meters. We decided that they were making a strike at the Vunakanau air base in support of the enemy’s operation at Guadalcanal, and therefore we returned to the myriad urgent details of planning that screamed for our attention.

One prime difficulty of our planning was the fact that the ships involved had never operated together as a fighting force. Except for Crudiv 6 ships, they had never so much as trained together in steaming in column formation. The speed standards of each ship had, therefore, not been adjusted, and we realized that great care would have to be exercised in making the frequent changes of speed required in the intricate formations of nighttime maneuvering. But the commander of each ship was a skilled veteran, and we felt sure that a maximum of effectiveness could be achieved in night battle by using a single-column formation.

Admiral Mikawa’s greatest concern was about the imperfectly charted seas of this region and the danger to his ships of unknown underwater reefs. He told me just after the battle that he was confident of victory once our ships had passed safely through the danger of the unknown waters. It was decided that the fleet would proceed southward through the central channel (“The Slot”) of the Solomons, on the advice of the commander of 8th Base Force, who said that it was almost deep enough for the battleships.

Thus the Eighth Fleet plan was completed, and by noon of August 7 it had been sent to headquarters. Captain Sadamu Sanagi, then one of the chief planners of the Naval General Staff, is my source for the reaction when this plan reached Tokyo. Admiral Osami Nagano, chief of the Naval General Staff, considered the plan dangerous and reckless, and, at first, ordered that it be stopped immediately. Upon further consideration and after consultation with his staff, he decided to respect the local commander’s plan.

Chokai entered Rabaul Harbor at 1400, just before the second air-raid warning of the day was sounded. It was a relief to learn that this time it was a false alarm, the planes were our own bombers returning from their mission. We had sent out a total of 27 “Bettys” and seventeen “Zekes” from Rabaul at 0730 to hit the enemy’s transports. The weather was bad at the enemy anchorage area, and these planes had attacked cruisers at 1120 with poor results. Nine “Vals” had left Rabaul later in the morning and attacked enemy destroyers at 1300, claiming damage to two of them. None of our search planes had sighted aircraft carriers this day, and our air losses came to five “Bettys,” two “Zekes,” and five “Va;s.”

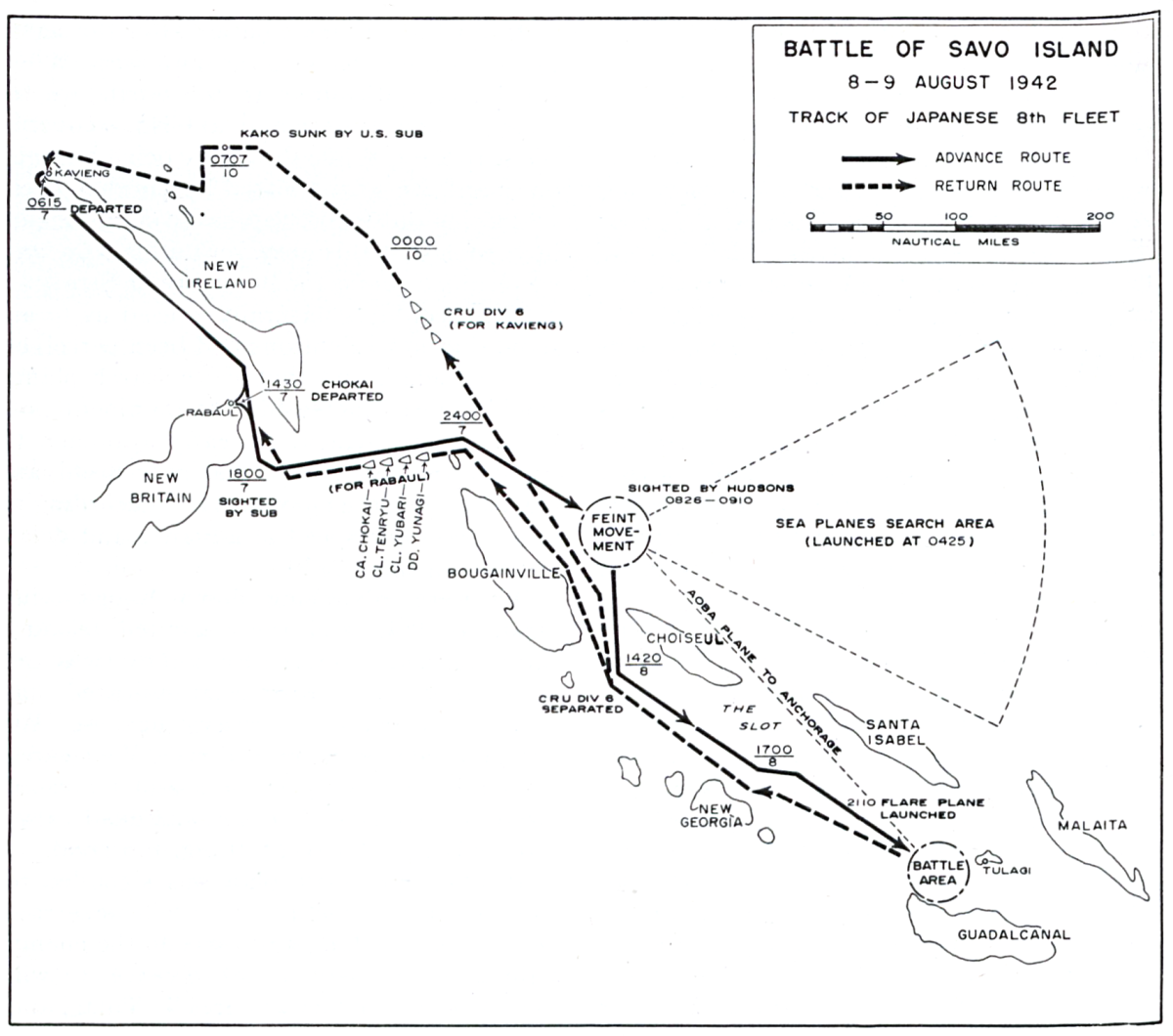

Admiral Mikawa and his staff boarded Chokai with all possible speed, and the flagship sortied from the harbor at 1430, accompanied by light cruisers Tenryu and Yubari and destroyer Yunagi. It was a fine clear day, the sea like a mirror. Our confidence of success in the coming night battle was manifest in the cheerful atmosphere on the bridge. Three hours out of Rabaul we rendezvoused with Crudiv 6, and thus it was that our seven cruisers and one destroyer were assembled for the first time. “Alert cruising disposition,” was ordered at a point fifteen miles west of Cape St. George. As darkness approached, an enemy submarine was detected to the south, and we altered course to the east to avoid it, which we did successfully. It was probably this same submarine whose torpedoes shortly claimed Meiyo Marti, which sank with the loss of crew and the 315 troops intended for Guadalcanal. This loss caused abandonment of our present plans to reinforce the island, and it was a bitter blow. The thought persisted then and later, however, that once the Army was dispatched in force, there would be no difficulty about driving the enemy from the Solomons. We continued southward, confident and, considering the circumstances, secure.

At 0400 next morning, five seaplanes were catapulted from our cruisers to reconnoiter Guadalcanal, Tulagi, and the surrounding waters. Aoba’s plane reported at 1000 that an enemy battleship, four cruisers, and seven destroyers had been sighted to the north of Guadalcanal at 0725, and fifteen transports at 0758. The same plane also reported the sighting of two enemy heavy cruisers, twelve destroyers, and three transports near Tulagi. The picture presented by this count of ships cast serious doubts on the results reported by our earlier air attacks, which had claimed two cruisers, a destroyer, and six transports sunk, plus three cruisers and two transports heavily damaged. It was concluded that most of the enemy’s invasion strength was still in the Guadalcanal area, and that although no carriers had been reported, they too must still be in the area, but probably to the south or southeast. We judged that if the enemy carriers were not within 100 miles of Guadalcanal, there would be little to fear of a carrier-based attack unless it came this morning, or unless we approached too close to the island before sunset. At any rate, the whereabouts of the enemy carriers was so important to our plan that Admiral Mikawa radioed to Rabaul for information about their location. We learned later that 25th Air Flotilla sent out reports of negative information on the enemy carriers, as the result of their morning reconnaissance flights, but this information did not reach us.

With the information at hand a signal was sent out to the effect that our force would proceed southward through Bougainville Strait, would recover float planes (at about 0900), and would then pass between Santa Isabel and New Georgia islands to approach Guadalcanal for a night assault against the enemy at about 2230.4

While pursuing a southeasterly course some thirty miles northeast of Kieta, we observed an enemy Hudson bomber shadowing us at 0825. We made 90-degree turns to port. to throw him off immediately after the sighting and headed back to the northwest. When the Hudson withdrew to the north, we reversed course at once and, at 0845, recovered the seaplanes. While they were being brought on board, we were spotted by another Hudson, flying quite low. Salvoes from our eight-inch guns sent this observer on his way, and we resumed course for Bougainville Strait.

These contacts naturally caused us to assume that our intentions had been perceived by the enemy, and that more search planes would appear, increasing the imminent possibility of air attack. An early approach to Guadalcanal became increasingly disadvantageous. The decision was made, accordingly, to decrease our speed of advance and delay our assault until 2330.

We were advancing down Bougainville Strait at 1145 and there sighted friendly planes returning toward Rabaul by twos and threes. The lack of formation indicated that they had encountered heavy fighting. We watched them with grateful eyes. We cleared the strait shortly after noon and increased speed to 24 knots. The sea was dead calm, and visibility was, if anything, too good.

At 1430 our battle plan was signalled to each of the other ships: “We will penetrate south of Savo Island and torpedo the enemy main force at Guadalcanal. Thence we will move toward the forward area at Tulagi and strike with torpedoes and gunfire, after which we will withdraw to the north of Savo Island.” While drafting this order, I had the firm conviction that we would be successful.

There was a tense moment on the bridge at 1530 when a mast was sighted at a distance of 30,000 meters on our starboard bow. Friend or enemy? We were much relieved to discover that it was seaplane tender Akitsushima, of the Eleventh Air Fleet. She was en route to establish a seaplane base at Gizo.

Meanwhile we were intercepting a great deal of enemy radio traffic. We heard, loud and clear, much talk of flight deck conditions as planes approached their landing pattern, such as “Green base,” and “Red base.” Happily, we could be fairly sure of no air attack from the enemy on the 8th, but it was made clear to our entire force that we could expect an all-out attack from their carriers on the following day. The very existence of the enemy flattops in the area was a major concern to Admiral Mikawa, and this dominated our later tactical concepts.

At 1630 every ship was ordered to jettison all deck-side flammables in preparation for battle. Ten minutes later the sun dissolved into the western horizon, and a message I had drafted for Admiral Mikawa was signalled to each ship in his name: “In the finest tradition of the Imperial Navy we shall engage the enemy in night battle. Every man is expected to do his best.”

After 1600 there was no further radio indication of enemy carrier activity. With the end of daylight and still no carrier-based air attacks, the chances of success for our ships looked much brighter, and spirits brightened in the flagship. The morale of the whole fleet climbed when we heard results of the morning attack by our planes. They, according to their reports, had hit two heavy and two light cruisers and one transport and had left them in flames.

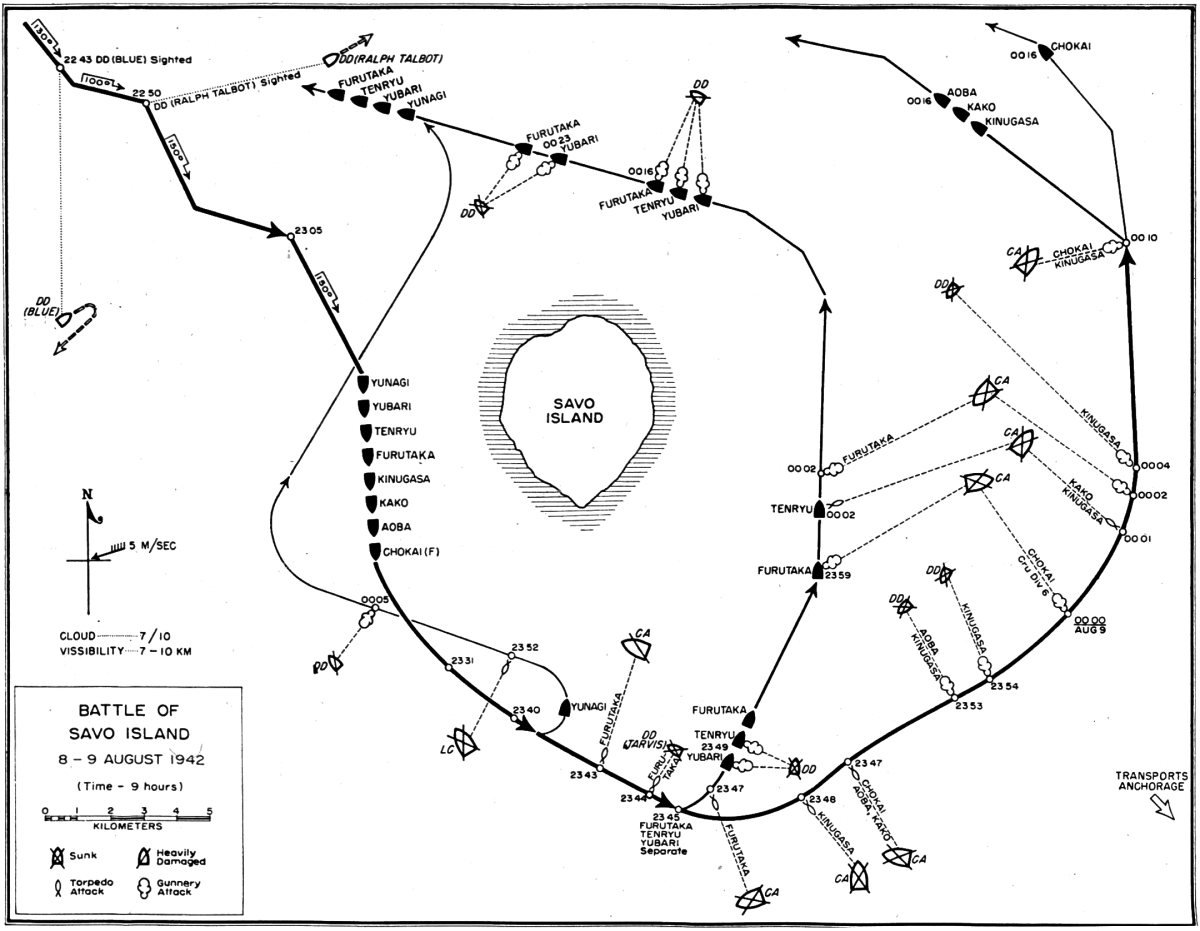

Just before dark our ships had assumed night battle formation, following the flagship in a single column with 1,200-meter intervals between ships. At 2110 the cruiser planes were again catapulted for tactical reconnaissance and to light the target area. The pilots had had no experience in night catapulting, so this was a risky business, but the risk had to be taken. A water takeoff would have necessitated our dispersing the formation, and then reforming, making for a delay which the schedule would not allow. The planes were catapulted successfully.

We encountered sporadic squalls at 2130, but these did not interfere with our advance. Long white streamers were hoisted to fly from the signal yards of each ship for identification purposes, and at 2142 speed was upped to 26 knots.

The catapulted seaplanes reported that three enemy cruisers were patrolling the eastern entrance of the sound, south of Savo Island. All hands were ordered to battle stations at 2200, and the formation turned up 28 knots. All was ready for combat. Narrow though the seas were in the battle area, we intended to adhere to the original battle plan: pass counterclockwise on the Guadalcanal side to the south of Savo Island, and then turn toward Tulagi.

At 2240, the unmistakable form of Savo Island appeared 20 degrees on the port bow, and the tension of approaching action was set three minutes later when a lookout shouted, “Ship approaching, 30 degrees starboard!”5 On the flagship bridge all breathing seemed to stop while we awaited identification of this sighting.

It was a destroyer, at 10,000 meters, about to cross our bows from right to left.

An order was radioed, “Stand by for action!”

Should we attack this target? We might be steaming into an ambush. At this moment the all-important question was whether we should strike this target or evade it. Admiral Mikawa made his decision and ordered, “Left rudder. Slow to 22 knots.” He had reasoned clearly that this was not the moment to alert the enemy to our presence, and at high speed our large ships kicked up a wake that would have been difficult to conceal. Breathing became more normal again as we watched the enemy destroyer’s movements. From her deliberate, unconcerned progress it was plain that she was unaware of us—or of being watched—and of the fact that every gun in our force was trained directly on her. Seconds strained by while we waited for the inevitable moment when she must sight us—and then the enemy destroyer reversed course! With no change in speed she made a starboard turn and proceeded in the direction from which she had come, totally unaware of our approach.

In almost the same instant, and before we could fully appreciate our good fortune, another lookout reported, “Ship sighted, 20 degrees port.”

A second destroyer!6 But she was showing her stern, steaming away from us.

Admiral Mikawa’s reaction was almost automatic, “Right rudder. Steer course 150 degrees.”

We passed between the two enemy destroyers, unseen, and they soon disappeared in the darkness. It was a narrow escape, but our emphasis on night battle practice and night lookout training had paid off. This advantage was later to be increased by the local situation in which the enemy’s backdrop was brightened by flames of burning ships, reflected from clouds, while we moved out of utter darkness.

But at the present moment the disadvantage to the enemy of lights and shadows gave rise to the further concern that once we had passed the line of the patrolling destroyers, the advantage of the lighting would be reversed against us. That this did not work against us in the next half hour must be attributed to plain good luck and the fact that the enemy was exhausted after many hours of exhausting alert during their landing operations. We were fortunate, too, that apparently there had been no report of our approach by enemy search planes.

It was time now for positive action, and, remembering the search-plane information that three enemy cruisers were patrolling south of Savo Island, we rushed in. The attack order was given at 2330. Battle was only moments away.

Speed of advance was pushed to thirty knots. Destroyer Yunagi, the rear of our formation, was ordered back to attack the enemy destroyers we had just bypassed. This move was more because of Yunagi’s inferior speed, which might have caused her to straggle from our attack formation, and also in the hope of securing our withdrawal route from disturbance by either of the two enemy destroyers patrolling north of Savo Island.

I stood beside Admiral Mikawa. Before me was a chart on which were plotted the locations of enemy ships. We peered into the darkness. The voice of a lookout shattered the tense silence: “Cruiser, 7° port!”

The shape which appeared in that direction seemed small; it could be only a destroyer. It was still a long way off.

“Three cruisers, 9° starboard, moving to the right!”

And then a parachute flare from one of our planes brought reality to the scene. There they were, three cruisers! Range, 8,000 meters.

Chokai’s skipper, Captain Mikio Hayakawa, was ready. His powerful voice boomed throughout the bridge, “Torpedoes fire to starboard—Fire!”

It was 2337.

Almost immediately the deadly weapons were heard smacking the water one by one. While we waited for them to hit, the radio announced that our following cruisers had opened fire with guns and torpedoes.

Then it happened. There was a sudden explosion which had to be a torpedo. It had struck an enemy cruiser which was on our starboard beam.

Our course was now northeasterly. Chokai launched a second set of torpedoes, and, following the first great explosion, there seemed to be a chain reaction. Within ten minutes after the first torpedo explosion, there were explosions everywhere. Every torpedo and every round of gunfire seemed to be hitting a mark. Enemy ships seemed to be sinking on every hand!

Our course was now northeast, and we sighted another group of enemy ships 30 degrees to port. Chokai searchlights illuminated these targets, and fire was opened on an enemy cruiser at 2353.

Chokai’s searchlights were used for the double purpose of spotting targets and also informing our own ships of the flagship’s location. They were effective in both roles, fairly screaming to her colleagues, “Here is Chokai! Fire on that target! . . . Now that target! . . . This is Chokai! Hit that target!”

The initial firing range of 7,000 meters closed with amazing swiftness. Every other salvo caused another enemy ship to break into flames.

For incredible minutes the turrets of enemy ships remained in their trained-in, secured positions, and we stood amazed, yet thankful while they did not bear on us. Strings of machine-gun tracers wafted back and forth between the enemy and ourselves, but such minor counter efforts merely made a colorful spectacle, and gave us no concern. Second by second, however, the range decreased, and now we could actually distinguish the shapes of individuals running along the decks of enemy ships. The fight was getting to close quarters.

From a group of three enemy ships the center one bore out and down on us as if intending to ram. Though her entire hull from midships aft was enveloped in flames, her forward guns were firing with great spirit. She was a brave ship, manned by brave men. But this ship immediately took a heavy list as our full fire-power came to bear and struck her. It appears, from post-war accounts, that this was the U. S. heavy cruiser Quincy, and she certainly made an impression on the men of our force. At short range she fired an 8-inch shell which hit and exploded in the operations room of Chokai, just abaft the bridge, and knocked out our No. 1 turret. We were all shocked and disconcerted momentarily, but returned at once to the heat of battle as Chokai continued firing and directing fire at the many targets.

As the range closed to 4,000 meters we saw that three enemy cruisers had been set afire by our guns. Enemy return fire had increased greatly in amount and accuracy, but we were still without serious damage. Then, almost abruptly, the volume of enemy gunfire tapered off, and it flashed in my mind that we had won the night.

There was an enemy cruiser burning brightly far astern of us as we ceased fire. I entered our operations room on Chokai and found it peppered with holes from shell fragments. Had the 8-inch hit on Chokai been five meters forward, it would have killed Admiral Mikawa and his entire staff.

We were still absorbed with details of the hard fight just finished and had lost all track of time. I was amazed to discover that it was just shortly after midnight, and that we were headed in a northerly direction. If we continued northward, we ran the risk of going ashore on Florida Island, so a gradual change in course was made to the left. I asked the lookout if there was any sign of pursuing ships. There was not.

While checking our position at the navigation chart desk, I heard someone say, “Gunfire, ahead to port!” I immediately went forward and stood beside Admiral Mikawa on the bridge.

Furutaka, Tenryu, and Yubari had taken a sharper turn to the left than the flagship and the others, when the first torpedoes had been fired, and had been pursuing a northward course, parallel to our own. We concluded that these three ships had cleared north of Savo Island and had again turned to the left where they found additional targets, and that it was their gunfire we now observed. We warned them by signal light of our presence while the gunfire continued.

Meanwhile, Admiral Mikawa and his staff had been making a rapid study of the situation in order to determine our next move. It was concluded that the force should withdraw immediately. This decision was reached on the basis of the following considerations:

- The force was at 0030 divided into three groups, each acting individually, with the flagship in the rear. For them all to assemble and reform in the darkness it would be necessary to slow down considerably. From their position to the northwest of Savo Island it would take 30 minutes to slow down and assemble, a half hour more to regain formation, another half hour to regain battle speed, and then another hour to again reach the vicinity of the enemy anchorage. The two and a half hours required would thus place our reentry into the battle area at 0300, just one hour before sunrise.

- Based on radio intelligence of the previous evening, we knew that there were enemy carriers about 100 miles southeast of Guadalcanal. As a result of our night action these would be moving toward the island by this time, and to remain in the area by sunrise would mean that we would only meet the fate our carriers had suffered at Midway.

- By withdrawing immediately we would probably still be pursued and attacked by the closing enemy carrier force, but by leaving at once we could get farther to the north before they struck. The enemy carriers might thus be lured within reach of our land-based air forces at Rabaul.

In making this decision we were influenced by the belief that a great victory had been achieved in the night action. We were also influenced by thought of the Army’s conviction that there would be no difficulty about driving the enemy forces out of Guadalcanal.

Admiral Mikawa received the opinion of his staff and, at 0023, gave the order, “All forces withdraw.”

There was no questioning of this order on the bridge of Chokai. The signal went out by blinker, “Force in line ahead, course 320 degrees, speed 30 knots.”

Chokai hoisted a speed light and withdrew. Shortly after the signal we sighted Furutaka’s identification lamp in the distance, and the battle was over. Our estimated dawn position was radioed to Rabaul in hope that Eleventh Air Fleet planes might be able to strike any pursuing enemy carrier.

Detailed reports were soon coming in from each ship concerning results achieved, damage sustained, and munitions expended. I went to the wardroom to prepare the action report for the force. The detailed report of shell consumption and casualties is given on the next page.

Reported claims came to a total of one light and eight enemy heavy cruisers and five destroyers sunk; five heavy cruisers and four destroyers damaged. But upon close analysis of the claims, and based on our view of the action from the flagship bridge, we estimated finally that five enemy heavy cruisers and four destroyers had been sunk.7 With Admiral Mikawa’s approval, this report was radioed to headquarters.

When my immediate tasks were completed I took a nap on the shelter deck. Shortly before 0400 I was awakened by the cry, “Battle Stations! All hands to Battle Stations!”

But the warning proved to be illusory. It was a fine morning. We continued northwest at full speed.

The hours passed, and no enemy planes were sighted. There was no indication at all of the enemy carriers whose transmissions we had heard so loud and clear on the previous afternoon. It was reassuring to know that we were not being followed, but our spirits were dampened by the thought that now there would be no chance for our planes to get at the enemy carriers.

Having witnessed the enemy air-raid on Rabaul two days before, we considered it dangerous to have all our ships at one base. Accordingly, at 0800, Crudiv 6 was ordered to separate south of Bougainville and head for Kavieng. They encountered an enemy submarine on the way, and cruiser Kako was sunk by its torpedoes at 0707 on the 10th. The three accompanying ships fought off the submarine and managed to rescue survivors from the stricken ship so that her total casualties were only 34 killed and 48 wounded. Aoha, Furutaka, and Kinugasa entered Kavieng at 1611 on the 10th.

|

Ships |

20 Cm. Gun |

14 Cm. Gun |

12 Cm. Gun |

8 Cm. Gun |

8 Cm. AA Gun |

25 Cm. Gun |

Torpedoes |

Depth Charge |

Casualties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Chokai |

308 |

|

120 |

|

|

500 |

8 |

|

34 killed |

|

Aoba |

182 |

|

86 |

|

|

150 |

13 |

6 |

|

|

Kako |

192 |

|

130 |

|

|

149 |

8 |

|

|

|

Kimigasa |

185 |

|

224 |

|

|

|

8 |

6 |

1 killed |

|

Furutaka |

153 |

|

|

|

94 |

147 |

8 |

6 |

|

|

Tenryu |

|

80 |

|

23 |

|

|

6 |

20 |

2 wounded |

|

Yubari |

|

96 |

|

|

|

|

4 |

|

|

|

Yunagi |

|

|

32 |

|

|

|

6 |

1 |

|

|

Total |

1,020 |

176 |

592 |

23 |

94 |

946 |

61 |

39 |

35 killed |

The activities of our Eighth Fleet submarines during this operation were uneventful. I-121 and I-122 had sortied from Rabaul on the 7th, had reached Savo on the 9th and sighted no enemy ships, but had maintained station, keeping in touch with lookouts ashore. I-123 started from Truk on the 7th, did not get to Savo until the 11th, and sighted no enemy; neither did RO-33, which came north from patrolling around Papua on the 7th and reached Savo on the 10th. RO-34 had proceeded northward from Australia and patrolled Indispensable Strait, but made no sightings.

Upon receiving our action report. Combined Fleet sent an enthusiastic message to Admiral Mikawa complimenting him on his success in this notable action. The withdrawal of Eighth Fleet without having destroyed the enemy transports has, since that time, come in for bitter criticism, especially after it was disclosed that the enemy carrier force was not within range to attack—and, most especially, after our Army was unable to dislodge the enemy from Guadalcanal. But critics should remember that Admiral Mikawa initiated and carried out this penetration on his own, without specific orders or instructions from Combined Fleet.

It is easy to say, now, that the enemy transports should have been attacked at all cost. There is now little doubt that it would have been worthwhile for Chokai to have turned back, even alone, ordering such of her scattered ships as could to follow her in an attack on the enemy transports. And, if all had followed and all had been sacrificed in sinking the transports, it would have been well worth the price to effect the expulsion of the enemy from Guadalcanal. The validity of this assumption, however, is premised on the fact that the survival of those transports accounted entirely for our Army’s subsequent failure to expel the enemy from its foothold in the Solomons.

The reasons for our early retirement were based in part on the Japanese Navy’s “decisive battle” doctrine that destruction of the enemy fleet brings an automatic constriction of his command of the sea. The concept of airpower (both sea-based and land-based), which invalidates this doctrine, was not fully appreciated by us at this time, nor were we fully convinced of it until the summer of 1944, and then it was too late.

Another reason behind our decision to withdraw was the lack of a unified command of our air and surface forces. Under the circumstances, we in the Eighth Fleet ships could simply not expect of our land-based planes the degree of cooperation required to cover us in a dawn retirement.

With the benefit of hindsight I can see two grievous mistakes of the Japanese Navy at the time of the Guadalcanal campaign: the attempt to conduct major operations simultaneously at Milne Bay and in the Solomons, and the premature retirement from the battle of Savo Island. I played a significant part in each of these errors. Both were a product of undue reliance on the unfounded assurances of our Army and of a general contempt for the capabilities of the enemy.

Thus lay open the road to Tokyo.

Admiral Mikawa’s Statement

Since Admiral Mikawa had been in command of the Japanese forces engaged in the Battle of Savo Island, he was requested to read Captain Ohmae’s article for accuracy. His comments follow:

I have read Toshikazu Ohmae’s article, “The Battle of Savo Island,” and find it well written and complete. It covers all the important facts of the battle as I remember them. There are a few points, however, which I wish to emphasize.

Upon my arrival at Rabaul, in late July 1942, as C-in-C Eighth Fleet, there was no indication that the quiet Solomons was soon to be the scene of fierce battle. Nevertheless, I recognized the mobile capability of U. S. carrier task forces and, accordingly, ordered my heavy cruisers to the safer rear base at Kavieng rather than Rabaul.

It was a serious inconvenience and a shortcoming that my command extended only to sea and land operations in the area. Air operations were entirely outside of my responsibility and control. I found, for example, that there was no program or plan for providing planes to the new base at Guadalcanal, and there was nothing that I could do about it.

As soon as the U. S. landings at Guadalcanal were reported on August 7, and the invasion strength was apparent, I determined to employ all the forces at my command in destroying the enemy ships. My choice of a night action to accomplish this purpose was made because I had no air support on which to rely—and reliable air support was vital to anything but a night action. On the other hand, I had complete confidence in my ships and knew that the Japanese Navy’s emphasis on night battle training and practice would insure our chances of success in such an action, even without air support.

My two major concerns for this operation were that enemy carriers might repeat against my ships their successes of the Battle of Midway before we reached the battle area, and that our approach to Guadalcanal might be hindered by the poorly charted waters of the Solomons. But both of these worries were dispelled once we had passed the scouting lines of enemy destroyers to the west of Savo Island, and I was then sure of success in the night battle.

The element of surprise worked to our advantage and enabled us to destroy every target taken under fire. I was greatly impressed, however, by the courageous action of the northern group of U. S. cruisers. They fought back heroically despite heavy damage sustained before they were ready for battle. Had they had even a few minutes’ warning of our approach, the results of the action would have been quite different.

Prior to action I had ordered the jettisoning of all shipboard flammables—such as aviation fuel and depth charges—to reduce the chance of fire from shell hits. While my ships sustained no fires, we observed that U. S. ships, immediately they were hit, burst into flames which were soon uncontrollable.

The reasons given by Mr. Ohmae for not attacking the transports are the reasons which influenced my decision at the time. Knowing now that the transports were vital to the American foothold on Guadalcanal, knowing now that our Army would be unable to drive American forces out of the Solomons, and knowing now that the carrier task force was not in position to attack my ships, it is easy to say that some other decision would have been wiser. But I believe today, as then, that my decision, based on the information known to me, was not a wrong one.

/s/ G. Mikawa

★

1. See Midway, The Battle that Doomed Japan, The Japanese Navy’s Story by Mitsuo Fuchida and Masatake Okumiya, U. S. Naval Institute, 1955.

2. Operation Watchtower, a s the Allied offensive was termed, employed one battleship, three carriers, 14 cruisers, 31 destroyers, 23 transports, six submarines, and lesser craft to a grand total of 89.

3. The initial American landing on Guadalcanal consisted of 11,000 U. S. Marines from sixteen transports.

4. The times given in this article are Zone −9, which was the Rabaul time kept by the Japanese. Allied forces were using Zone −11 time. Accordingly, the main action opened at 2337 Japanese time and two hours later by Allied time.

5. The U. S. destroyer Ralph Talbot.

6. This ship was the U. S. destroyer Blue.

7. Four cruisers, the USS Astoria, Quincy, and Vincennes and the Australian Canberra, were sunk, over a thousand Allied naval personnel killed, and the Chicago and Ralph Talbot severely damaged.