This html article is produced from an uncorrected text file through optical character recognition. Prior to 1940 articles all text has been corrected, but from 1940 to the present most still remain uncorrected. Artifacts of the scans are misspellings, out-of-context footnotes and sidebars, and other inconsistencies. Adjacent to each text file is a PDF of the article, which accurately and fully conveys the content as it appeared in the issue. The uncorrected text files have been included to enhance the searchability of our content, on our site and in search engines, for our membership, the research community and media organizations. We are working now to provide clean text files for the entire collection.

It might be fairly said that the Naval Historical Foundation was mothered by necessity and fathered by the U. S. Naval Institute. Mother Necessity in this case, very much unlike most mothers, took a negative form; whereas Father Institute ran true to masculine form in both the inception and babyhood of the offspring.

The logic of the situation asserted itself more by accident than design. In 1926 the Naval Institute Proceedings published an article by the writer entitled “Our Vanishing History and Traditions.” It was principally a plea to rescue records and relics constituting source material of naval history, that were gradually vanishing from loss, deterioration, or destruction. The importance of doing so was stressed: “When we look forward several hundred years and vision the maturity of the United States—her magnitude in all things material and her leadership in all things cultural and spiritual—we begin to realize how important it is to the advancement of civilization that the record of the origins and early development of this potential giant of a country should be carefully preserved.”

To quote further, “The influence of naval and maritime affairs upon the course of the nation’s history has been very much greater than can possibly be recognized by the average person.” This because in these fields very much less has been done than in most others towards preservation of source material and their effective use in public education. The article made no definite suggestions as to corrective measures. It merely concluded that the then principal current need was to arouse interest, and predicted that once “keen interest in the matter exists, official and unofficial ways and means will be exerted towards filling the great gaps” in source materials.

The prime movers in what followed appear to have been Captain Harry A. Baldridge, the present head of the Naval Academy

Museum, who was then Secretary-Treasurer of the Naval Institute and editor of its Proceedings, together with General George Richards, U. S. Marine Corps, a member of the Board of Control. With the publication of the article appeared a “Board of Control’s Special Notice” beginning:

“The Board of Control is so impressed with the timeliness of Captain Knox’s article in this issue, entitled “Our Vanishing History and Traditions,” that it deems it worthy of special notice, and sincerely trusts that there will be created such a lively interest as will result in the adoption of a successful plan.”

The notice then called attention to two published “discussions” of the article, one by Admiral Strauss suggesting the creation of a trust fund, and concluded:

“The Board of Control is in hearty sympathy with this suggestion and believes that the Naval Institute should render all possible assistance towards preserving the records in question; and has, in fact, under consideration the contribution of a substantial sum to such fund if created.”

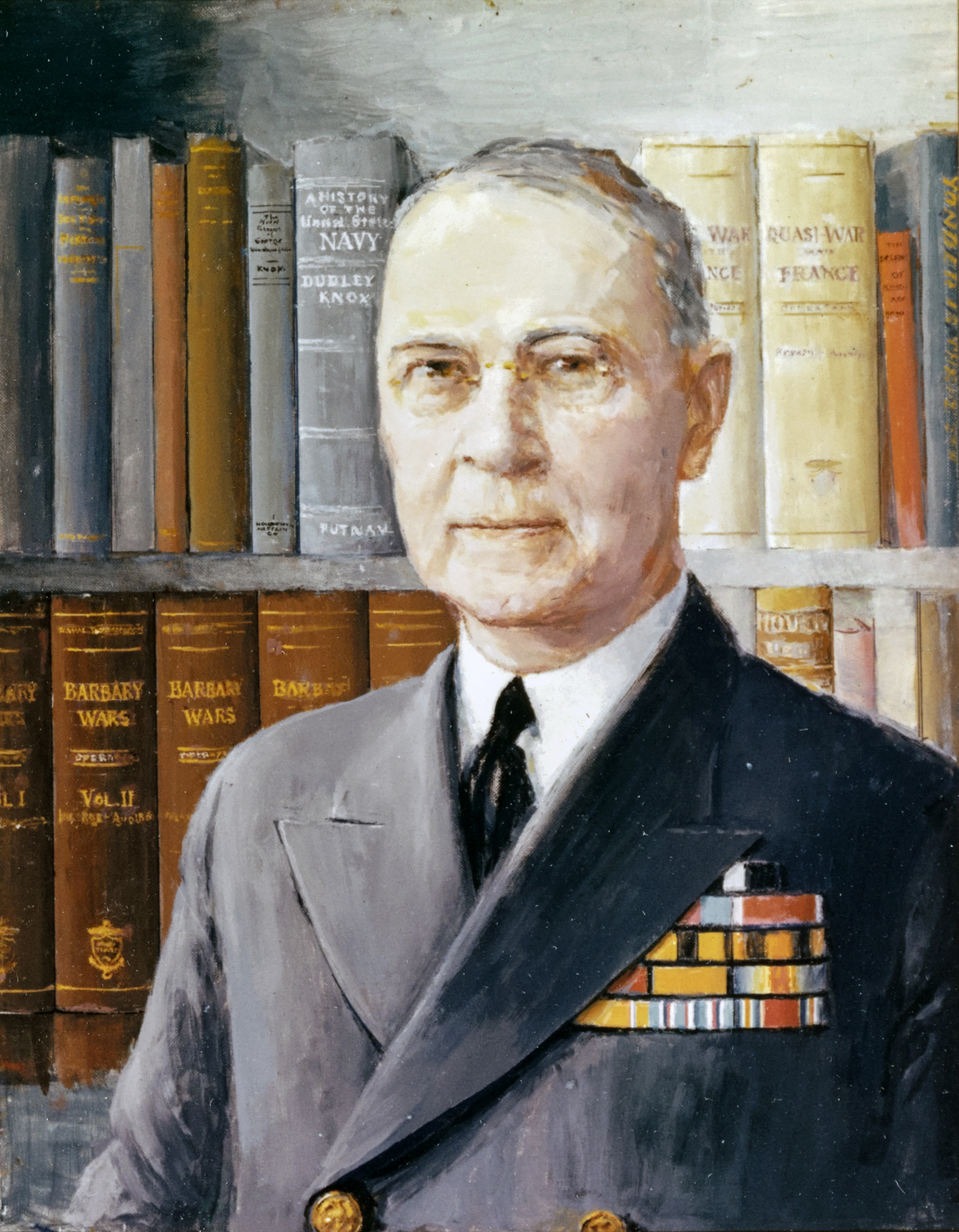

Commodore Knox, a graduate of the Naval Academy in 1896, has served in three wars. But he is best known to the Navy and the general public as a leading naval writer and historian. For many years he was in charge of the Office of Naval Records and Library, Navy Department. He was one of the founders and for many years the secretary of the Naval Historical Foundation.

All of this was on a background of the nonexistence of any private society of national scope in this field. The old Naval History Society had functioned well for some years under the leadership of Mr. James Barnes. His personal collection of unique naval manuscript, books, pictures, and objects formed the nucleus around which the valuable collection of the Society was built. The Society also performed an important educational function in publishing a large series of

historical manuscripts. In about 1925, however, the basic character of the Society changed. Arrangements were made for transferring permanent custody of the collections to the New York State Historical Society, with the understanding that it was therein to become the “Barnes Memorial Library,” as it did ultimately. The printing of documents gradually stopped, together with active collection of historical source material.

Thus this national society became merely part of a state society. The historical society was transformed into merely a library. The educational function in its publication aspect ceased, as well as the collection function to a great extent. This unfortunate deterioration of worthwhile activities of national scope and interest was the background for the organization of the Naval Historical Foundation.

The unsought support of the Naval Institute was so encouraging that the incorporation of “The Naval Historical Foundation” was decided on. The Incorporators were the Honorable Curtis D. Wilbur, Secretary of the Navy, Dr. J. Franklin Jameson, the eminent head of the Manuscript Division of the Library of Congress, Admirals Austin M. Knight and Hilary P. Jones, General George Richards, Rear Admiral Elliot Snow (C.C.), and Captain D. W. Knox. Upon organization in 1926 Admiral Knight was elected as President, and these formalities were scarcely completed before Captain Baldridge personally delivered the Institute’s check for $1,000. Most generously this initial contribution was increased to $5,600 during the next twelve years.

The principal purposes of the new society were defined in its Articles of Incorporation as:

“The collection, acquisition and preservation of manuscripts, relics, books, pictures, and all other things and information pertaining to the history and traditions of the United States Navy and Merchant Marine.

“The diffusion of knowledge respecting such history and traditions, either by publication or otherwise.”

The objectives were further stated to be “educational and literary, in the interest of American naval history and the fostering of patriotism.”

The activities of the Foundation have not duplicated, but have effectively supplemented those of the Navy Department. It has assisted by prompt action in collection work where the Navy would find accomplishment difficult or impossible. Its manuscripts and other collections serve the Navy, and are also available to the general public for historical reference and study. Pictures and relics are ear-marked for exhibit in the projected official naval museum in Washington, with the mission of educating the American people in naval and maritime affairs. Thus there is no conflict with the Naval Academy Museum, which has the primary function of educating and stimulating the morale of Midshipmen. However the Foundation habitually lends exhibits to the Naval Academy.

The Collections

Dedicated originally to salvage of valuable source material, the Foundation has well justified its creation. By far the greater part of its collections have been donated by persons seeking permanent preservation and care of their materials in the custody of an organization capable of utilizing them properly. Purchases have been made but rarely, and then only when unique items could be obtained at moderate cost and saved from probable neglect, unfortunate dispersion, or loss.

Its documents number approximately 100,000, composed principally of letters, reports, professional note-books, order-books, letter-books, journals, diaries, log-books, and the like. Among the early large collections given were those of (1) the two Admirals Selfridge, 1816-83, (2) Admiral Stephen B. Luce, 1842-1917, (3) Admiral Silas Casey, 1871-1920, (4) Admiral John Rodgers, 180962, (5) Surgeon Horner, 1826-72, (6) Admiral S. C. Rowan (loan), 1826-89, (7) William B. Clark, copies of Revolutionary documents, (8) Commodore Dulaney, 180955, (9) Admiral Roe, 184-D75, (10) Commodore Marston, 1852-62, (11) Captain H. A. Wise, 1850-98, (12) Admiral E. D. Taussig, 1867-78, (13) Lieutenant Gantt, 1834-48, (14) Captain Schoomaker, 1857—88, (15) Josiah Fox, 1795-1810, (16) Admiral H. J. Russell, 1861-75, (17) Commander H. B. Sawyer, 1827-59, (18) Commander Francis

1481

Battle between the U.S.S. Monitor and the C.S.S. Merrimac at Hampton Roads, March 9,1862. The Naval Historical Foundation hopes some day to raise the Monitor, now lying on the ocean floor off Cape Hatteras.

Winslow, 1833-63, (19) Commodore Radford 1847-70. Other similar collections have been and continue to be given. Recently Vice Admiral Forrest Sherman presented his original copies of Japanese surrender documents.

There are upwards of 10,000 pictures, many of unique and special interest. They constitute among the largest of such collections in the field of marine art, and are of great interest historically. The Miss Powell collection includes nearly 1,000 engravings. Miss Watson gave 138 paintings and pictures formerly belonging to the son of Admiral Farragut. Mrs. Chadbourne gave about 50 Japanese prints related to Perry’s visit, besides two paintings. Mrs. Eberstadt gave 1,500 naval prints by European masters dating back to the 16th century. Mrs. Dunlap gave about 20 rare Civil War prints. A large number of interesting pictures have been acquired singly, a few by purchase.

The considerable collection of relics varies from ship-models and statues to weapons, uniforms, and buttons.

The Foundation’s maritime books number about 2,500, some of them being very rare.

Educational Activities

In conformity with its educational mission, as funds have permitted, rare documents and charts have been published by the Foundation. Illustrating this is the facsimile of the Navy’s first regulations: “Rules for the Regulation of the Navy of the United Colonies of North America,” published in 1775, and taken from the only known copy, that in the Yale University Library. Also a recruiting broadside, “Great Encouragement for Seamen,” issued by John Paul Jones in 1777, in connection with the fitting out of the good ship Ranger at Portsmouth, New Hampshire, for a cruise to France. Other items are the “Early History of the U.S. Revenue Marine Service” by Captain Horatio Smith of that service, as well as a hand- colored contemporary French map of the naval and military operations about York- town in 1781, indicating the important part that sea power played in the American Revolution.

The publication (limited edition) of the narrative “Admiral Dewey and the Manila Bay Campaign” by Commander Nathan Sargent is now in hand. This was written by Admiral Dewey’s direction and under his close supervision. It constitutes the Admiral’s own account of his operations leading to the capture of Manila in 1898, giving many details never before published. The document was unavailable for many years, and only recently was presented to the Foundation by the Admiral’s son, Mr. George G. Dewey. This project illustrates an essential service of the Foundation—the making available in printed form of important historical source material.

One exhibit is now already arranged to make better known the part that the Navy, Coast Guard, and Merchant Marine have played in the history of our country. Through the courtesy of the Society of the Cincinnati, our own collection of materials dealing with the naval side of the Revolution, together with other objects very kindly loaned, are permanently on display at Anderson House, 2118 Massachusetts Ave., N. W., Washington, D. C., the Headquarters of the Society.

General Washington’s broad grasp of the importance of sea control and its use in combined operations, along with the decisive influence of naval power in the Revolution, are too little appreciated. These facts are well illustrated by the exhibit.

Future Plans

A strong effort is in order to bring together in Washington the evidence of the worthwhile accomplishments and gallant deeds of our Navy and Merchant Marine the world over, so that the sea records may be more complete for future historians and for public education and inspiration. This is an essential continuing service of the Foundation, which must now be prepared to meet the colossal requirements of World War II.

Hence it is plannfed to extend the historical period exhibits into a series that eventually can be brought together in the proposed Government Naval Museum in Washington. The Tripoli and 1812 Wars, with the deeds of such leaders as Stephen Decatur, will form the subject for the next exhibition. Should the Museum referred to fail to materialize the Foundation will consider organizing one. In this connection it is fortunate in having associated with it those of outstanding ability in naval antiquarian matters, restoration work, and museum organization and procedure.

The project for the purchase of the William Paul house and lot in Fredericksburg, Virginia, is a continuing one dependent on the raising of sufficient funds. It was here that John Paul Jones as a young man visited his brother and became Americanized. From here he set forth to offer his services to the Continental Navy.

Ship raising projects include furthering the salvage of (1) the U.S.S. Monitor sunk off Cape Hatteras in 1863; (2) vessels of Arnold’s Fleet, Lake Champlain, 1776-77; (3) Macdonough’s Squadron, Lake Champlain, 1814.

Future plans include the printing in limited editions of the following manuscripts now owned by the Foundation:

Christopher Prince’s Autobiography.

Diary of the Expedition to open Japan, 1853, by William Speiden, Jr.

Vol. Ill, Vice Admiral W. L. Rodger’s work on the “History of Naval Warfare”—from the unedited manuscript.

In the category of pictures, charts and maps, it is planned to make limited reproductions of the following:

An oil painting of the Continental frigate Alliance entering Boston Harbor in 1781. Reproduction to be made in full color. This painting is owned by the Foundation.

Drawings of the U. S. privateer Snap Dragon, 1812, from builder’s half model owned by the Foundation.

American merchant ship Harriet of Georgetown, 1793, from the rare engraving by Grenwaggen in the Foundation’s Eberstadt Collection.

Original drawing of naval activity during the Mexican War, to be selected.

Original drawing of naval activity during the Civil War, to be selected.

The Agate painting of the loss of the U.S.S. Peacock. Reproduction to be in color. This painting is owned by the Foundation.

The wash drawing of the Battle for Leyte Gulf, 1945.

Finances

The Foundation has been very “Scotch” in the handling of its meager funds, which today total about $20,000. The point has now been reached where its financial resources should be greatly strengthened. Its work has quite outgrown the heretofore voluntary basis of clerical assistance, and the generosity of friends in furnishing rent- free space. Money is needed for maintenance and repair of collections, for expenses indidental to exhibits, and for the occasional purchase of historical materials, especially when prompt action is necessary to save items of unique historical value. A revolving fund is very much needed for the reproduction of rare manuscripts and pictures and for the printing of manuscript.

A strong endowment fund is a basic essential, if the Foundation is effectively to discharge its patriotic mission of salvaging the records of the many splendid deeds of the Navy, as well as the Marine Corps, the Coast Guard, and the Merchant Marine.

★

FRENCH AS SHE IS SPOKEN

Contributed by LIEUTENANT COMMANDER THOMAS E. FLYNN

U. S. Naval Reserve

A few days after the invasion of North Africa, a certain old battleship was coming into the harbor at Casa Blanca. It was getting on toward dark, and the Captain was very anxious to get tied up. It happened that the tugs at Casa Blanca were manned by French speaking crews. Not knowing French himself, the Captain passed the word down for some one who could speak French to report to the bridge. In short order, a certain enterprising storekeeper presented himself as having a working knowledge of the language. Working against time, the Captain immediately asked this volunteer to order the tug alongside. Obediently, the storekeeper picked up the megaphone and shouted:

“Breeng ze tug along side of ze sheep!”

(The Proceedings will pay $5.00 for each anecdote submitted to and printed in, the Proceedings.)