One of the most important contributions ever made to the naval records of our Revolutionary War was the recent discovery of six accurately executed drawings showing the ships of Count D'Estaing in American waters during the year 1778. For this we are indebted to the Carnegie Institution of Washington, whose systematic search of French archives for American historical material found these exceedingly interesting pictures in the Louvre.

The mere probability of the coming of D'Estaing's fleet, like some invisible gigantic hand, had pulled the greatly superior British Army out of the perfect security of Philadelphia, and sent it scurrying on forced marches across New Jersey, in retreat before much smaller numbers of American troops weakened by the epic rigors at Valley Forge.

Arriving at the Delaware entrance barely too late to intercept the British transports carrying their army's heavy baggage from Philadelphia to New York, the French Admiral followed to the latter point but declined to attack there in en-operation with Washington's army, and chose instead an enterprise against Newport, then held by a second British army of 6,000 men.

At Rhode Island, D'Estaing allowed the unexpected appearance of an inferior British squadron to divert him from an apparently certain victory of major proportions ashore, and then was finally persuaded to abandon the promising opportunity there because of damages to his ships from a severe gale. After proceeding to Boston for repairs the fleet sailed for the winter operating theater in the West Indies.

Few Americans of Revolutionary times ever saw this seemingly mysterious power from overseas which had so suddenly lifted up the sacred banner of their independence and dashed it down again in the very face of victory. History has reserved until our present generation the universal privilege of viewing this fleet as it actually appeared, at least to the eyes of a careful artist with much seagoing experience. Moreover, we have the further advantage, from our knowledge of subsequent events, of being better able to understand the great benefits derived from D'Estaing's operations on our coast, and the truly profound influence of French sea power in general upon the winning of our independence. These newly found pictures prove the wisdom of the ancient Chinese saying that one picture is worth a thousand words.

The first of the pictures portrays the capture of the British frigate Mermaid, 28 guns, in Delaware Bay, near Cape Henlopen, on July 8, 1778, the day of D'Estaing's arrival there.1 The Mermaid was chased ashore, as shown, by several French frigates, and, after throwing overboard all her guns, struck to a small American ship which hailed her.

That the small vessel standing out from the wreck may be American is indicated by the difference in her size and type from the other ships under way, and by the fact that on her the French ensign is not prominently displayed and made conspicuous by the magnification of artistic license. The French ensign of that period was a white ground with numerous fleur-de-lis and a central figure in gold. She apparently flies a different flag.

D'Estaing's failure to bag his enemy in the Delaware was partly due to his unusually long transatlantic passage, but a factor of equal importance was the wise energy with which the British Admiral Howe had taken precautionary measures. At the first warning of a probable Franco- American alliance and the fitting out of a French fleet at Toulon, Howe had concentrated his small forces from New York and Newport at Delaware Bay, where he was in position to give protection to the vital water communications of the army in Philadelphia. Preparations were at once made to evacuate the latter place, the principal embarrassment being insufficient shipping to embark both the army and its baggage together with numerous civilian sympathizers.

It was consequently decided to march the army by land to New York and send the heavy artillery and stores by water. The very day that the sea forces reached New York, and with the army still but half way across New Jersey, a dispatch vessel arrived which had sighted and been chased by the French fleet near the American coast, probably near Chincoteague, Virginia, where D'Estaing took pilots. The situation had indeed been a precarious one for the British, and it continued to be critical because of the great naval inferiority of Howe. There was still the possibility of the French Admiral forcing his way into New York Harbor before the British army could cross to the city.

With great energy, Admiral Howe prepared to dispute the passage which would have meant ruin to the British cause in America. His heaviest ships were anchored in line across the deep channel just inside Sandy Hook, with springs on their cables. Here also was placed a large storeship, hastily armed with shore artillery, manned by soldiers. The frigates and smaller vessels formed a mobile reserve to give aid where most needed.

In this position Howe covered the movement of the British army by water from Sandy Hook to New York City on July 5, three days before D'Estaing reached the Delaware. Grimly Howe held and strengthened his position while word was received of the arrival of the French fleet and its passage towards New York. Here D'Estaing found him on July 12, as may be seen in the second illustration to this article.

In the foreground is shown the French fleet after most of it had anchored. It was composed of twelve ships of the line and five frigates, besides several smaller vessels among which were three corvettes of 36 guns each. Some of these ships hold a special interest for us. The flagship Languedoc, 80 guns (probably shown near the right side of the picture with the admiral's flag at the mizzen), was afterwards present at the fleet action off the capes of the Chesapeake preceding Yorktown. So also were the flagship Cesar, 74; the Marseillaise, 74; and the Zélé, 64.

The frigate Provence in 1781 was in the squadron of De Barras which, coming from Newport to re-enforce De Grasse, just missed being in that fleet action. De Barras himself, on the present occasion, was in command of the Zélé. The frigate Concorde became famous in 1781 for her repeated success in carrying dispatches overseas between Washington and De Grasse, to arrange the joint military-naval concentration at Yorktown which decided the war. The Fantastique, 64, here with D'Estaing, was commanded by the famous Suffren who was later so successful in Indian waters.

Besides the ships named above the following also were present off New York in 1778, and doubtless form part of this interesting picture: the flagship Tonnant, 74; the Artésien, 64; the Protecteur, 64; the Guerrière, 64; the Amphion, 64; the Vengeur, 64. In the frigate class were the Prudente and Andromaque of 40 guns each, and the Amiable and Chimère of 36 guns. Some of the smaller vessels shown were corvettes, besides merchant ships employed in supplying the fleet.

During the eleven days that D'Estaing remained at this anchorage there was an extremely interesting interchange of correspondence between him and Washington, the more important dispatches being delivered by the hand of Colonel Laurens. Washington was eager for an immediate joint attack on New York, his army being then about to cross the Hudson some fifty miles north of the city. His sound and comprehensive plan included the use of Continental naval forces in Long Island Sound to cut off much-needed British sup plies which were due from overseas, and which it was to be expected would be diverted to this route. It was Washington's first venture in naval strategy, a field in which subsequent experience was to give him great eminence.

Admiral D'Estaing, himself a soldier also, hesitated to force the passage in the face of Howe's determined preparations. There was some question as to the sufficiency of water over the bar for the larger French ships which were of unusually deep draft, and the pilots furnished by Washington are said to have advised against the attempt. British officers who were present, on the other hand, maintained that at high tide there was thirty feet depth on the bar, compared with a maximum draft of twenty-four feet for the French ships. At any rate, D'Estaing finally decided against the New York enterprise and on July 22 sailed for Newport, then also held by a British army against American land forces to the north. With characteristic eagerness to do all in his power to cooperate with naval forces, Washington at once sent urgent orders to General Sullivan, before Newport, to have pilots ready, to raise more troops, and to assist the Admiral in every way possible in a joint attack.

Upon arrival off Newport on July 29, D'Estaing anchored in the approaches to the central or main channel, which leads between Conanicut Island and the vicinity of what is now Fort Adams, and received a prompt call from General Sullivan. The next day two ships of the line under Suffren were sent up the western channel, between Conanicut Island and the mainland, and anchored within it after sustaining slight damage from British batteries on the island. Two frigates and a corvette entered the eastern channel, or Sakonnet River, and caused the British to abandon and burn a small frigate and some galleys there. The investment of the British army of 6,000 men in Newport was now complete; all channels leading into the harbor being blocked by French ships, while Generals Sullivan and Lafayette occupied land positions to the north with nearly 10,000 American troops.

The British soon evacuated Conanicut Island, and on August 5 the two French ships in the western channel rounded the north end of that island and anchored, their former places in the channel being taken by two other ships of the line. At this stage the British burned or sank five frigates which drew too much water to enter the inner harbor of Newport.

With his remaining eight ships of the line, accompanied by a frigate, D'Estaing forced the main channel on August 8. We see them in the third picture with Beaver Tail on their port beam and quarter, and under fire from land batteries on the starboard hand. Beyond the batteries are seen burning vessels which are probably British fireships. The French Admiral reported that in this operation,

orders were given to spare the town as much as possible. . . the loss in men was very small . . . a few balls lodged in the hulls and in the rigging, very few, fortunately, in the masts . . . there was much noise and fire.

Once past the batteries the Admiral anchored this squadron above Goat Island (where one battery stood) and was there joined by the four heavy ships which had operated in the western channel. The 4,000 troops embarked in the fleet were promptly landed on Conanicut Island for purposes of refreshment and organization, preliminary to a future junction with Sullivan's army. There seemed to be no alternative for the British forces in Newport except to surrender within a few days, and such a reverse coming ten months after Burgoyne's capitulation at Saratoga with 3,500 men may well have meant the loss of the war.

Here was a striking illustration of the profound influence which sea power may exert upon land operations. Another such example was the lightning-like rapidity with which sea power saved the apparently hopeless situation at Newport for the British. Most unexpectedly Howe's substantially re-enforced squadron arrived from New York on August 9 and anchored near Point Judith, only 8 miles away. Howe was still considerably weaker than the French fleet, his 13 ships of the line aggregating much less power than D'Estaing's 12. He had come merely on the chance of profiting by "an opportunity which might offer for taking advantage of the enemy" and on arrival reported to General Pigot, commanding at Newport, that it was "impracticable to afford the General any essential relief."

The effect upon Admiral D'Estaing, however, was quite astonishing. He temporarily abandoned his major mission, so clearly in course of early accomplishment, for the sake of an ill-considered diversion which in the end proved to be the undoing of the primary task. The French troops on Conanicut Island were immediately reembarked in the fleet, and on the following morning D'Estaing hastily cut his cables and with a fresh wind astern ran past the batteries again. The picture of this second forcing of the main channel once formed a part of the set here reproduced but unfortunately has been lost.

The British fleet was too greatly inferior to accept action and ran before the wind, followed by the faster French ships for two days and the intervening night. In the late afternoon of the second day, August 11, the French van had nearly overtaken the British rear.

Respecting this situation D'Estaing's report reads,

The maneuvers of Lord Howe, who continued to run before the wind but closed up his intervals, showed that he no longer hoped to avoid battle. The wind and sea were rising. By a quarter of six our advance guard was strung out along behind the English rear guard, and engaged it as it came about, . . . the weather became worse and thicker with very heavy squalls. . . .

The fourth picture represents the scene at about this time. The French van is in the foreground, being struck by a squall. The main French fleet is seen in the distance at the right, while the British fleet is in two columns at the left. By some ac counts Howe had kept three fire ships in tow, but had sent his bomb ketches and galleys with one frigate to New York. The lateness of the hour together with the rough and threatening weather decided D'Estaing to break off the engagement. He never should have sought it; there was too much at stake at Newport, where Howe could have interfered with the Franco- American operations only on the most disadvantageous terms and with forbidding risks. Newport could have been taken despite him.

During the succeeding night a severe gale scattered both fleets and damaged many ships. D'Estaing reported that on his flagship, the Languedoc, "the bowsprit broke, then the foremast, then the maintop, then the mizzenmast; finally the mainmast fell. Our rudder broke next. This last misfortune was the greatest of all." The Marseillaise, 74, had only her mainmast standing when the weather moderated. At an anchorage at sea, temporary repairs were made to the French fleet which then limped back to the offing of Newport, arriving on August 20, ten days after its dashing sally.

Meantime Howe had escaped to New York, and General Pigot had reported to him.

The rebels had advanced their batteries within 1,500 yards of the British works. He was under no apprehension from any of their attempts in front, but should the French fleet come in, it would make an alarming change. Troops might be landed and advanced in his rear, and in that case He could not answer for the consequences.

This was the situation when D'Estaing arrived with his crippled ships just outside the harbor. Some of them were in no condition to force the main passage or even to work through the western channel unresisted. Yet there was reasonably good protection against weather in the approaches to both channels, where a favorable wind could be awaited to enter Narragansett Bay by the unfortified western route. Howe was not to be feared unless substantially re-enforced.

In any case, there were nearly 4,000 troops in the fleet whose "effect" would be decisive at an early date if brought properly to bear against British defenses ashore. Contrary to these weighty considerations D'Estaing decided in favor of immediately proceeding to Boston to refit his fleet in preparation for later operations in the West Indies which his instructions required. The West Indies at that period were the richest commercial region in the world; the chief ambitions of France lay there, and doubtless they were very prominently in the Admiral's mind.

The decision to withdraw the fleet was communicated to General Sullivan on the 20th, and in spite of the earnest entreaties of the latter and other high officials, the Admiral sailed for Boston on the following day. In the fifth picture we are given an excellent idea of the appearance of the fleet on the occasion of this departure from Newport. Prominently in the foreground is the badly battered Languedoc with the improvised steering gear and jury-rig clearly shown. On her port hand is probably the Marseillaise, which it will be recalled lost her fore and mizzenmasts in the gale and here carries no mizzen topgallant yard. The remainder of the fleet shows no signs of the lesser disabilities which must have been general. It is likely that the Admiral had transferred to one of the leading ships for this trip, since his flag is apparently not flying on the Languedoc.

The picture shown of the Artésien, 64, is not a part of the rare set under discussion, but has been copied from La Marine Francois by Lieutenant Maurice Loir, and is included here because the ship was attached to D'Estaing's fleet, and a good "close up" is given.

The fleet arrived at Boston on August 28, mooring in Nantasket Roads. D'Estaing reported that:

We needed above all else masts and bread . . . M. Ozanne, naval constructor, was sent to Portsmouth, a neighboring port which used to furnish masts for part of the English Navy, but with all his zeal and effort was able to secure only masts suitable for a vessel of 64 guns.

There were four ships of greater size in the fleet, including the lately dismasted flagship and the similarly damaged Marseillaise.

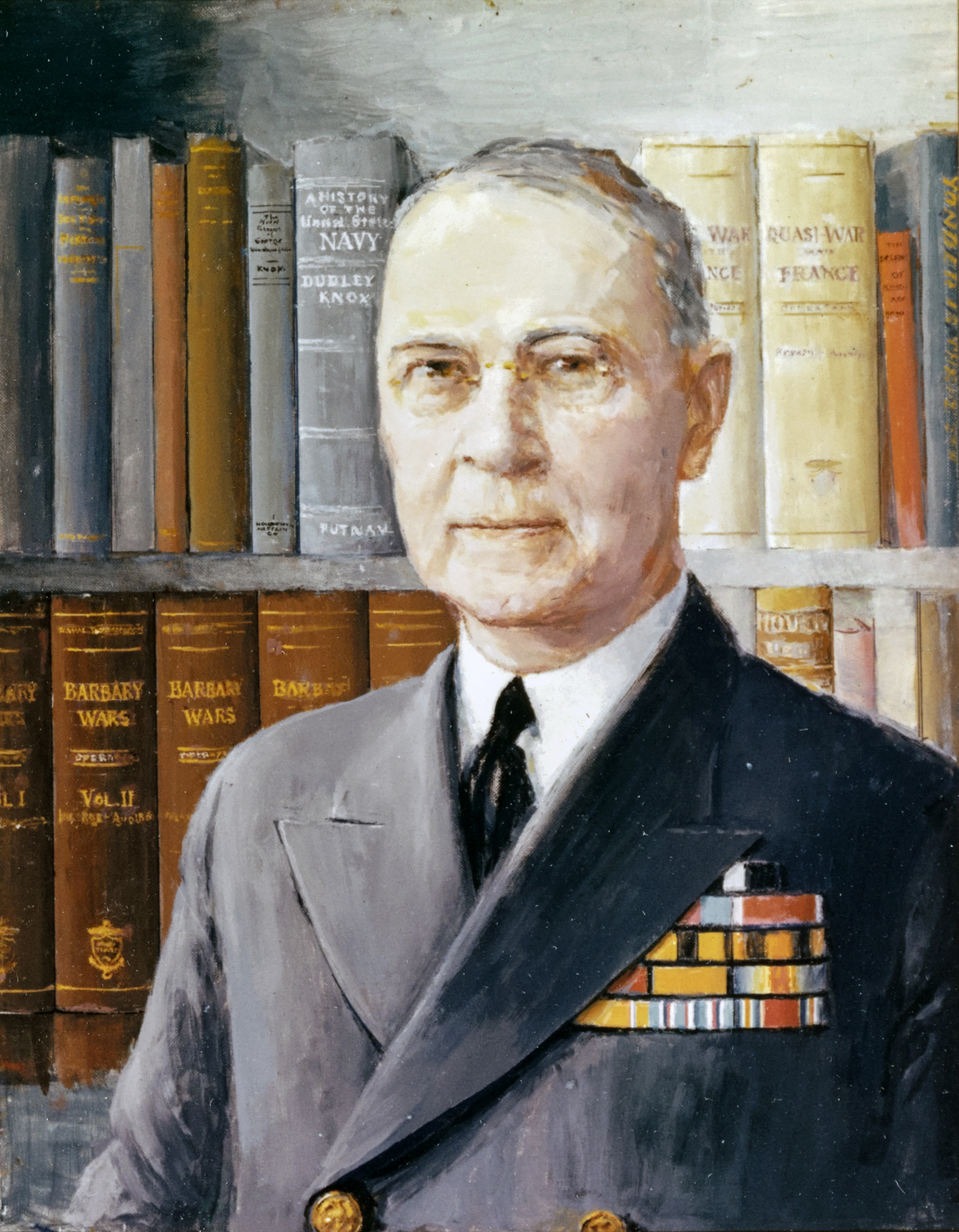

Naval Constructor Ozanne is the talented artist to whom American and French naval history are so much indebted for this invaluable set of drawings, and the next view is that of Portsmouth, N. H., with its lively harbor of that early maritime period. The vessel in the foreground is probably a French corvette from the fleet.

Ozanne's naval service began in 1757 when he was appointed professor of drawing for naval cadets, and in that capacity made two cruises in American waters. He was commissioned assistant naval constructor a short time before D'Estaing's fleet sailed from Toulon. Dr. W. G. Leland of the Carnegie Institution of Washington informs us that Ozanne

had an honorable career in the Navy, making several other voyages and being employed in responsible positions as constructor, artist, engineer, and administrator in various ports.2

D'Estaing's difficulties in obtaining bread at Boston may have equalled those with respect to masts. Because of its untimely departure from Newport the fleet was coldly received at the "Hub," and heated criticism of its retreat was carried on in the Boston press, with rioting in the streets against the French. Lafayette made a special trip from Newport to urge D'Estaing's return there, and obtained an offer to march the French troops overland to that front, but without the support of the ships. Rather than accept this proposal, the American army was withdrawn from the island of Rhode Island to the mainland, Lafayette being the last person to cross over.

The general effect of D'Estaing's operations in our waters in 1778 was very naturally extremely disappointing to the struggling patriots of that day. Their hopes had been raised so high at the coming of the fleet that their chagrin and criticism were correspondingly sharper at its failure. Many bitter things were said and printed of the gallant D'Estaing and his brave fleet.

From the unemotional viewpoint of many decades afterwards we can be more generous and grateful, even while we point to mistakes which were made in spite of the best intentions and most earnest efforts. Mahan avoided severe direct criticism of D'Estaing by eulogizing Howe.

Summarizing Howe's accomplishments in the campaign Mahan says:

With a force inferior throughout, to have saved in one campaign the British fleet, New York, and Rhode Island, with the entire British army, which was divided between those two stations and dependent upon the sea, is an achievement unsurpassed in the annals of naval defensive warfare. It may be added that his accomplishment is the measure of his adversary's deficiencies.

The deficiencies are clear and Mahan has not overdrawn them by his indirect method. Unquestionably D'Estaing held both British armies, with their supporting fleet, in the hollow of his hand, and permitted all to escape him. Yet it seems but just to ascribe the deficiencies which brought about this sorry showing, very largely to the then already outworn system of often putting former soldiers in command afloat. D'Estaing was a victim of this practice.

Such training was obviously quite inadequate for the development of that mature naval judgment which is indispensable for success in high command afloat. It made for undue caution when the decision rested upon maritime technology, and for difficulty in differentiating between justifiable boldness and indiscreet rashness. It led to reliance upon the ever unreliable council of war, and to the undue influence of certain trusted subordinates whose own judgment might well have been faulty. The choice between conflicting advice is doubly difficult in the absence of competent judgment on the part of the chooser, who must then be perpetually torn between irresolution and blind action.

D'Estaing's conduct of the campaign was marked by these unfortunate characteristics, which necessarily had their origin in the deficiencies of his early training and in the administrative system which nevertheless placed him, more soldier than sailor, in command of the fleet. This is Well worthy of our serious consideration now, when unwise proposals would consolidate the War and Navy Departments.

But while pointing out the grave failures of this campaign for the sake of the lessons which lie therein we should not overlook its great accomplishments. The forced evacuation of Philadelphia was of highly important moral and material benefit to the American cause. Another result of inestimable value was the naval awakening of Washington.

The narrow margin by which the British had escaped complete defeat was a revelation to our great Commander in Chief regarding the decisive importance of sea power, and the one certain road to complete victory which it offered. Throughout the remaining three years of the war he thought only in terms of joint military-naval operations, and the sum and substance of his military strategy was to hold his army in readiness to co-operate with a superior French fleet, the coming of which he never ceased to hope, plead, and plan for.

After the 1778 naval operations we have discussed, D'Estaing went to the usual West Indian winter operating theater, where he had several inconclusive encounters with British forces. In early September of 1779 he made an unsuccessful attack on Savannah lasting six weeks. Washington begged him in vain to come up for a joint attack on New York, submitted a comprehensive plan, and promised to "exert all the resources of the country in a vigorous and decided operation." In preparation the Continental Army was greatly augmented, but Washington would not employ the troops actively after he learned that the fleet had sailed for France.

Upon the arrival of Rochambeau in July, 1780, with a large re-enforcement of French troops, Washington laid down as a cardinal condition for the active employment of that army, in co-operation with his own, that

In any operations, and under all circumstances a decisive naval superiority is to be considered as a fundamental principle, and the basis upon which every hope of success must ultimately depend.

In summing up the succeeding campaign of 1780 he wrote to Franklin,

Disappointed. . . especially in the expected naval superiority, which was the pivot upon which everything turned, we have been compelled to spend an inactive campaign, after flattering prospects at the opening of it.

We need only refer to the campaign of the following year which culminated in the capitulation at Yorktown, after Washington had finally succeeded in obtaining his long sought naval superiority and carried out his own plan for using it in co-operation with the land forces. This was the final fruition of Washington's naval genius which was rooted in the operations of D'Estaing's fleet, so clearly portrayed to us in the remarkable set of pictures shown herewith.

* * *

After the foregoing had been written, Charles H. Taylor, Esq., of Boston, presented the Navy Department Library with an old painting depicting the arrival off Point Judith on July 11, 1780, of the French squadron and convoy of transports which brought the Count de Rochambeau and his army of 6,700 troops. A reproduction of this painting is added herewith.

The expedition comprised seven ships-of-the-line, five frigates, and four small armed vessels convoying thirty-six transports. The escort was under the command of the Chevalier de Ternay. At daybreak of July 11, in a thick fog, a transport warned the fleet of land ahead, and as the fog lifted Point Judith was sighted about three miles distant. The shore lookout station displayed the French flag and flew a signal prearranged by Lafayette: "Rhode Island in American hands and welcome."

In the foreground of the picture are shown the heavy ships of the escorting squadron while in the distance, somewhat obscured by fog, are the numerous transports. Near the center may be seen what is presumably the standard of the Count de Rochambeau flying at the main on board the flagship Duc-de-Bourgogne of 80 guns. Two of the vessels present, the Provence, 64, and the frigate Andromaque, had been in the fleet of D'Estaing in 1778.

As a part of the Yorktown campaign in 1781 this squadron proceeded under De Barras from Newport to Lynhaven Bay with the object of re-enforcing De Grasse. The latter, however, was then engaged with the British fleet south of the capes, so that De Barras failed to make the junction, although he participated in the subsequent naval operations in Chesapeake Bay. The squadron convoyed troop down the Chesapeake, landed heavy al tillery from Newport and Providence for the siege of Yorktown, and finally blockaded the mouth of the York River until the surrender.

This final picture is therefore appropriate as a part of the set previously shown, because it not only contains some ships of D'Estaing's 1778 fleet but also shows us the ships which took part in the final decisive victory of the Revolution.

D'Estaing's fleet made the first gesture of French sea power in our aid. Its influence fell short of being decisive because of the failure to take full advantage of the opportunities offered. Nevertheless, it revealed the potency of sea power, and pointed the way for the effective employment of land power's handmaiden a s finally accomplished at Yorktown.

1 Some sources report this incident as having happened at Sinepuxent, Md., about 30 miles south of Cape Henlopen.

2 The Carnegie Institution of Washington has rendered both countries a great service by discovering these drawings and publishing them in the school edition of its News Service Bulletin issued in July, 1933. The writer is much indebted to that institution for a set of photographs from the original negatives, and for permission to publish them.