EDITOR'S NOTE: This article gives a history of early education in the Navy, and of efforts made from 1777-1845 to establish a proper naval school. It carries through to the establishment of a school in the Naval Asylum at Philadelphia, and to its removal to Annapolis, where, in 1845 by order of George Bancroft then Secretary of the Navy, the present Naval Academy was founded.

Probably no other national institution has been so largely created by the executive branch of the government as the United States Naval Academy. Not until the Civil War did Congress manifest any particular interest in naval education, and not until the Spanish-American War did it appropriate money liberally for that purpose. The people were even more indifferent than Congress. On the other hand, from the founding of the Navy in 1794 to the establishment at Annapolis of the Naval School in 1845, the most progressive Presidents, every Secretary of the Navy (with possibly one or two exceptions), and many naval officers advocated the extension and improvement of the educational facilities of the Navy. Under these circumstances, the early efforts in behalf of naval education took one of two forms: (1) movements to obtain legislation in behalf of a naval academy, and (2) administrative measures of the Navy Department establishing and encouraging naval schools. All early attempts to move Congress to pass a law instituting a naval academy failed. Some of these fruitless efforts will be first considered.

One of the first, if not the first, recommendations for the establishment of a school or schools for the instruction of the officers of the American Navy was made by Captain John Paul Jones early in the American Revolution. It is to be found in his "Plan for the Regulation and Equipment of the Navy," which was drawn up at the request of the President of the Continental Congress, and which was dated Philadelphia, April 7, 1777. Jones proposed to establish an "Academy" at each of three dockyards, "under proper masters, whose duty it should be to Instruct the Officers of the Fleet when in Port in the Principles and Applications of the Mathematicks, Drawing, Fencing and other manly Arts and Accomplishments." He further proposed to test the abilities of the young men who applied for commissions in the Navy by an appropriate examination. He would also have them serve a certain term in "Quality of Midshipmen, or Masters mate" before they were examined for promotion.1

The earliest plans for a naval school that were formulated after the adoption of the Constitution provided for such an institution in connection with a school of the Army. In June 1798, Alexander Hamilton, Inspector-General of the Army, in view of the disturbed relations then existing between the United States and France, recommended several measures for placing the country in a state of defense. One of these was the establishment of an "academy for military and naval instruction." In November, 1799, he sent to Secretary of War McHenry an elaborate plan for a military academy, which provided for five schools: a fundamental school, a school of engineers and artillerists, a school of cavalry, a school of infantry, and a school of the Navy. Young men preparing for the naval service were to spend two years in the fundamental school studying the general branches of knowledge, before entering the school of the Navy, after which they were to receive instruction for two years in spherics, astronomy, navigation "with the doctrines of the tides," and naval architecture. "To admit of exemplifications of naval construction and exercises," Hamilton proposed to locate his school on navigable waters. In a very general way, the present course of instruction at the Naval Academy follows Hamilton's plan.2

In a report on a military academy, which McHenry made to President John Adams in January, 1800, Hamilton's plan, slightly changed, again appears. McHenry proposed to send the naval officers on practice cruises, in which they were to be "exercised in the manoeuvers and observations most useful in service, and be instructed in whatever respects rigging of vessels of war, pilotage, and the management of cannon." When McHenry's successor as secretary of war, Samuel Dexter, proposed to establish a school for artillerists and engineers, President Adams and Secretary of the Navy Stoddert agreed that it would be highly useful to the Navy, and that midshipmen ought to be admitted to the school. On the establishment of the Military Academy in 1802, notwithstanding this recommendation, no provision was made for the instruction of naval officers. The notion of a joint school for the Army and the Navy was not, however, at once abandoned. In 1808, President Jefferson, who wished to centralize federal administration at the capital under the watchful eye of the government, favored the removal of the Military Academy at West Point to Washington and the extension of its benefits to the naval service.3

Previous to the War of 1812, it was by no means clear to Jefferson and the Democrats that a Navy was an essential institution to a peace-loving democracy. During the war, however, the Navy won its way into popular favor by its gallant exploits, and its permanency was for the first time assured. By the end of the war, the spirit of nationalism was at high tide, the Navy had reached its maximum size, and the need of some means of instruction for the many young and unschooled midshipmen was strongly felt. Obviously, the time was ripe for a movement to establish a naval academy separate and distinct from the Army school.

On November 15, 1814, Secretary of the Navy William Jones took occasion in a communication to the Senate on the reorganization of the Navy Department to "respectfully suggest the expediency of providing by law for the establishment of a naval academy, with suitable professors, for the instruction of the officers of the navy in those branches of the mathematics and experimental philosophy, and in the science and practice of gunnery, theory of naval architecture, and art of mechanical drawing, which are necessary to the accomplishment Of the naval officer. The project was favored by some of the leading naval men. Captains Samuel Evans and Thomas Tingey said that a naval academy would be beneficial to the service. On the other hand, doubtless not a few officers agreed with Captain Charles Stewart that the "best school for the instruction of youth in the profession is the deck of a ship."4 Early in 1815 the subject of establishing a naval school came up in both the House and Senate, but nothing was accomplished.

From 1814 to 1845 an agitation for a professional school of the Navy similar to the Army school at West Point was conducted in Congress, in the Navy Department, and in the Navy. During this period every Secretary of the Navy, with the possible exceptions of George E. Badger and Thomas W. Gilmer, whose terms of office were brief, recommended either to Congress or to the President the establishment of a naval school or schools. These secretaries were William Jones, B. W. Crowninshield, Smith Thompson, Samuel L. Southard, John Branch, Levi Woodbury, Mahlon Dickerson, James K. Paulding, Abel P. Upshur, John Y. Mason, and George Bancroft. It should also be said that the first three Secretaries of the Navy, Benjamin Stoddert, Robert Smith, and Paul Hamilton, were disposed to increase the meager educational facilities of the Navy, and that Hamilton suggested the sending of midshipmen on their entrance into the service to the naval hospitals for instruction in navigation and other sciences connected with their profession. For the thirty years preceding 1845, the correspondence between the Secretaries of the Navy and the naval committees of Congress on the establishment of a naval school was extensive. Various bills providing for one or more naval schools were drafted by the secretaries or other friends of naval education and introduced in Congress. Of these bills, two passed the Senate, but all of them failed in the House.

The most uncompromising opponents, as well as the most zealous advocates, of a naval school were to be found among the officers of the Navy. The opinion was by no means uncommon that book-learning and the theory of the naval and kindred sciences, and even refinement and cultivation, were incompatible with the professional duties of a sea-officer. On the other hand, especially among the younger men of both the line and the staff, there was a growing demand that the government should improve professional equipment, elevate the character, and broaden the culture of the midshipmen. Among the lieutenants of the Navy, the most ardent advocates of a naval school were A. S. Mackenzie, L. M. Powell, M. F. Maury, and J. H. Ward. Mackenzie and Maury championed the cause of naval education in the periodicals of their day. Of the naval staff, Chaplain George Jones and Professors William Chauvenet and J. H. C. Coffin were the most active. Chaplain Jones drafted plans for a school and besieged the Navy Department and Congress to adopt them. In 1836 fifty-five of the junior officers of the Constitution and Vandalia petitioned the Secretary of the Navy and Congress to establish a naval academy.5

Various arguments were advanced by the friends of naval education. A professional school, they said, was as essential to the Navy as to the Army. Moreover, since the midshipmen entered the Navy at an early age and were assigned such duties on shipboard and in the navy-yards as precluded much advancement in learning, they needed to be grounded not only in professional studies, but also in the more general and more literary branches of education. The tone of the Navy needed to be elevated, its discipline improved, and the temper of its officers mollified. The inadequacy of the teaching of the schoolmasters at sea and in the navy-yard schools was pointed out. President John Quincy Adams, a typical New Englander in his encouragement of science, learning and morality, conceived that the midshipmen of the Navy might acquire practical seamanship at sea, "but a competent knowledge even of the art of shipbuilding, the higher mathematics, and astronomy; the literature which can place our officers on a level of polished education with the officers of other maritime nations; the knowledge of the laws, municipal and national, which, in their intercourse with foreign states and their governments, are continually called into operation; and, above all, that acquaintance with the principles of honor and justice, with the higher obligations of morals and of general laws, human and divine, which constitutes the great distinction between the warrior-patriot and the licensed robber and pirate—these can be systematically taught and eminently acquired only in a permanent school, stationed upon the shore and provided with the teachers, the instruments, and the books conversant with and adapted to the communication of the principles of these respective sciences to the youthful and inquiring mind." 6

President Adams and his Secretary of the Navy, Samuel L. Southard, earnestly and continuously endeavored during their administrations to secure adequate provision for the education of naval officers. Southard again and again recommended the establishment of a naval school. As a site for it, he favored Governor's Island, New York, a most excellent location. The encouragement of naval education formed a part of President Adams' policy of nationalism and paternal government. In three of his four annual messages, he recommended the establishment of a naval school. Bills based upon the recommendations of Adams and Southard were in 1826 introduced in the two houses of Congress, but failed of passage. The House bill provided that the school should be located on any lands then held by the United States for naval or military purposes. It authorized the President to appoint from the captains of the Navy the "Commandant" of the school. The corps of instructors was to consist of a professor of natural and experimental philosophy and astronomy, a professor of mathematics and navigation, a teacher of geography and history, a teacher of the French and Spanish languages and a fencing master.7

The "Bill for the Gradual Improvement of the Navy," which passed the Senate on February 17, 1827, provided among other measures for a naval academy. Its provisions on this subject were similar to those of the House bill of the previous year, but they were less specific in their details and left more to the discretion of the President. The establishment of a naval academy was ably and eloquently advocated in the Senate by Robert Y. Hayne, of South Carolina. General William Henry Harrison of Ohio, Ashur Robbins of Rhode Island, and William Smith of Maryland spoke in its behalf. Hayne's colleague in the Senate from South Carolina, William Smith, made the chief speech in opposition. After having stated that Julius Caesar, the Duke of Marlborough, the Maid of Orleans, Generals Brown, Miller, and Scott, and Colonel Towson were not educated in military academies, Smith proceeded to draw some conclusions respecting naval education from our experiences in the late naval war of 1812-15. "Where were Hull and Bainbridge raised?" he exclaimed. "Was it in an academy that they gained their knowledge of ships, their dauntless courage, and presence of mind, or the address which ensured their success? They were, if he did not mistake, engaged previous to the war in the merchants' service." Here, he said, was to be found the great school in which naval officers and seamen were to be instructed; and it was dangerous to close the Navy to those who were educated in it. In the House an amendment to strike out the clause relating to the naval academy was carried by a vote of 86 to 78. The Senate acceded to the amendment of the House by a vote of 22 to 21. By these narrow majorities this measure was defeated, and the establishment of a naval academy postponed for many years. The failure of the measures of 1826-27, as well as of many similar ones, may be ascribed to the disinclination of Congress to increase the expenditures and powers of the government, partisan opposition, and the lack of unanimity in the Navy respecting the establishment of a school. Moreover, at this time, many men honestly held that the naval profession was an art to be acquired at sea, and not a science to be learned in schools.8

With the advent of steamships, the Secretaries of the Navy discovered a new argument; for officers must now understand the laws of physics and the workings of marine engines. Secretary Upshur, in 1841, was the first to urge this consideration. Upshur showed considerable ignorance of the educational needs of the Navy, for he brought forward a plan providing for the establishment of three or five naval schools, one each at Norfolk, Newport, and Boston, and possibly Pensacola and some convenient point on the Great Lakes. For purposes of discipline, government and instruction, he proposed to attach to each school, a captain, a commander, two lieutenants, two passed midshipmen, two professors of mathematics, one teacher of foreign languages, a chaplain, a surgeon, an assistant surgeon, and two engineers. The students were to consist of both officers of the Navy and applicants for the position of midshipman. They were to be instructed in mathematics, navigation, and the French, Spanish, Italian and German languages. In July, 1842, a bill embodying in the main Upshur's plan was introduced in the Senate. It provided for the establishment of five schools at as many unoccupied fortifications of the Army, which were to be transferred from the War to the Navy Department. The bill was wisely amended by the Senate so as to provide for the establishment of but one school, and this one at or near Fortress Monroe, Virginia. It passed the Senate, but failed in the House. For the second time the latter body, reflecting the general views of the nation, showed itself less favorably disposed to the cause of naval education than the Senate.9

In December, 1842, January, 1844, and January, 1845, Senator R. H. Bayard, of Delaware, introduced bills in the Senate providing for the establishment of a naval school or schools. Bayard, who was chairman of the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs, manifested much interest in naval education. His bill of January, 1845, authorized the establishment of a naval school "under the direction of the Secretary of the Navy, on board of a vessel of the United States, in connection with Fort Norfolk, on Elizabeth River, in the State of Virginia, as a shore station." The curriculum of the proposed school provided for two courses of study, of eighteen months each. The preliminary course was to be pursued by candidates for admission into the Navy, and the advanced course by midshipmen after they had served three years at sea and as a preparation to an examination for promotion. Bayard estimated that seven naval officers and ten teachers would be needed, and that the expense of the school would be considerably less than that of the existing corps of naval professors. The bill was reported favorably by the Senate Committee on Naval Affairs, and received the approval of Secretary of the Navy Mason. Congress, however, adjourned on March 3, 1845, without acting on it.10

From these futile efforts to obtain a naval school by legislation, let us turn to the work of the Navy Department, first in providing schools on naval vessels at sea and within or near the navy-yards, and later in establishing a naval school at Philadelphia.

In 1794, when the Navy under the Constitution was founded, the office of schoolmaster had for many years been established in the British Navy. The ancient schoolmaster was a warrant officer, who taught all the youths of his ship the rudimentary branches of a general and professional education. He was required to instruct the "Voluntiers in Writing, Arithmetick, and the Study of Navigation, and in whatsoever may contribute to render them Artists in that Science." Before admittance to the Navy, he had to pass an examination before the "Master, Wardens, and Assistants of the Trinity-House of Deptford- Strand"; and he must produce a certificate "under the Hands of Persons of known Credit, testifying the Sobriety of his Life and Conversation."11

Our first naval laws made no provision for a seagoing pedagogue, but this deficiency was early supplied by administrative authority. During our naval war with France, 1798-1801, schoolmasters were employed on board the smaller frigates and ships of war. Their pay and emoluments were fixed by President John Adams at thirty dollars a month and two rations a day. Adams wished to establish a school on board every frigate. On the first cruise of the ship Boston during the war with France, her school master taught thirty persons navigation and other naval sciences.12 The chaplains at this time performed in addition to their other duties those of the schoolmaster. They were assigned to the larger ships, and the schoolmasters to the smaller.

On January 2, 1813, the office of schoolmaster was established by law.13 An act of this date authorized the construction of four seventy-four-gun ships and provided that each of them should carry a schoolmaster, who was to be appointed by the captain and was to receive $25 a month and two rations a day. In 1816 additional ships of the line and additional schoolmasters were authorized. Under the rules of the department, the employment of schoolmasters on board the smaller vessels was continued. According to a rule in force in 1832, no vessel of the size of a sloop of war was to sail without a schoolmaster, "if one can be had." Usage permitted the captain to choose his naval pedagogue, but if he neglected this duty the appointment might be made by the department. The schoolmasters were appointed for a single cruise. With little pay, short tenure, and low official status, they were few in number and weak in pedagogical ability. Secretary Southard gave them the more dignified name of "professors of mathematics." In 1835 Congress adopted this name and placed the naval professor upon a more permanent footing by creating the naval Corps of Professors of Mathematics, and raising his pay to $1200 a year.14 An appropriate entrance examination was now prescribed. As a result of these measures, the quality of the naval teachers was greatly improved, and within a few years several new men entered the new corps, whose abilities and achievements were of a high order. Among the most distinguished of the early professors were McClure, Chauvenet, Lockwood, Coffin, and Yarnall. The number of professors of mathematics in 1845 was twenty-two. In 1848 the number was fixed by law at twelve. The observers of the Naval Observatory have been largely recruited from this corps.

The chaplains often performed the duties of naval schoolmasters, and on at least one occasion an army officer acted in this capacity—Lieutenant C. G. Smith, of the Military Academy. Smith conducted a naval school on board the corvette Cyane, Captain J. D. Elliott, during a cruise on the coast of Brazil in 1826-27.15 For many years a large part of the work of naval instruction fell to the chaplains. They made more efficient teachers than such schoolmasters as could be had for $25 or $30 a month, and it was in part for this reason that they were so often assigned pedagogical duties. The schoolmasters sometimes found their lowly station a stepping-stone to the more exalted and better paid position of naval chaplain. For instance, Rev. George Jones, one of the ablest chaplains of the Old Navy, entered the service as a schoolmaster. So closely were the two offices connected, that, on ships where no chaplain was employed, the schoolmaster was sometimes called upon to conduct religious exercises or to perform other duties of a minister of the gospel. Indeed, in selecting chaplains, the Navy Department at times looked to their pedagogical qualifications rather than to their excellence as divines. The regulations of the Navy, which specified the duties of the chaplain as teacher, were modeled in part upon the British regulations respecting schoolmasters. Those of the American Navy for 1802 assigned to the chaplain the duty of a schoolmaster. "To that end," in the quaint language of the regulations, "he shall instruct the midshipmen and volunteers in writing, arithmetic, navigation, and in whatsoever may contribute to render them proficient. He is likewise to teach the other youths of the ship, according to such orders as he shall receive from the captain. He is to be diligent in his office, and such as are idle must be represented to the captain, who shall take due notice thereof."16

The principal branches taught in the floating schools of the Navy were mathematics and navigation. Bowditch's practical, though superficial, treatise was the chief textbook for both subjects. Sometimes instruction was given in the rudiments of the French and Spanish languages. The hours of instruction were usually from nine or ten o'clock in the morning until noon. The quarters assigned for a school were such as could be had. Occasionally the captain lent his forward cabin. More often the schoolroom was on deck, separated by a mere canvas partition from the manifold noises of four or five hundred seamen. On sloops of war it was situated in the dimly-lit steerage. The schoolroom on shipboard is described by Chaplain Walter Colton as a "sort of thoroughfare, and is a living echo of the incessant din of all that is doing upon deck. The builders of Babel with their countless hammers and unintelligible tongues scarcely sent up a clamor of more confused sounds than what descends from the deck of a man-of-war. There is no noisy trade from the sledge and anvil of the smith to the hammer and awl of the cobbler that is not here pursued with its customary disrespect of silence. Add to this the rush of surging sea that never sleeps and the frequent cloud speaking in tempest and thunder, and we have a faint representation of the human and elemental uproar in the midst of which the demure disciple of Pythagoras attempts to erect his quiet schoolroom and exercise his contemplative functions. A man who in such a situation could preserve the continuity of his mental abstractions would hardly lose his philosophical composure amid the tumults of an earthquake or even the falling fragments of a dissolving universe."17

The schoolmaster at sea labored under many disadvantages. He had no authority to compel obedience or command attention to his instruction and precepts. The midshipmen looked down upon him as a landlubber, a rankless non-militant and a civilian idler. Moreover, until 1842 when Congress came to his relief, the naval pedagogue was often quartered on board with his pupils and slept and ate with them. His sleeping quarters, however, might be assigned "in the cockpit, below the midshipmen." Sometimes he messed in the "starboard steerage." His familiar association with his pupils, his lowly station, and his rankless office, made impossible the exercise of the rightful authority of a pedagogue. Moreover, only two-thirds of his pupils could attend school at one time, since the remaining third must be on duty. Of those who attended, one-half had been on deck from midnight until four o'clock in the morning, and the other half from four until eight o'clock. Under these circumstances the pupils were inevitably dull and listless. Besides, they were liable to be called from the schoolroom at any time to help with the work of the ship. It is not surprising that frequently the schoolmaster, after vainly trying to keep school at the beginning of his cruise, abandoned formal instruction, and turned his attention to teaching individually the few bright and inquiring minds that were bent on obtaining knowledge.

The picture of the schoolmaster at sea during the third and fourth decades of the nineteenth century which was drawn by Lieutenant Matthew F. Maury from his own experience may be shaded a trifle too darkly. Maury tells us that the first ship that he sailed in had a schoolmaster from Connecticut. "He was qualified and well disposed to teach navigation, but not having a schoolroom, or authority to assemble the midshipmen, the cruise passed off without the opportunity of organizing his school. From him, therefore, we learned nothing. On my next cruise, the dominie was a Spaniard; and, being bound to South America, there was a perfect mania in the steerage for the Spanish language. In our youthful impetuosity we bought books, and for a week or so, pursued the study with great eagerness. But our spirits began to flag, and the difficulties of ser and estar finally laid the cope-stone for us over the dominie's vernacular. The study was exceedingly dry. We therefore voted both teacher and grammar a bore, and, committing the latter to the deep, with one accord declared in favor of the Byronical method—

'Tis pleasant to be taught in a strange tongue

By female lips and eyes—

and concluded to defer our studies until we should arrive in the South American vale of paradise, called Valparaiso."

Maury's next schoolmaster was a "young lawyer, who knew more about jetsam and flotsam than about lunars and dead reckoning—at least, I presume so, for he never afforded us an opportunity to judge of his knowledge on the latter subject. He was not on speaking terms with the reefers—ate up all the plums for the duff, and was finally turned out .of the ship as a nuisance." Another of Maury's teachers he described as an "amiable and accomplished young man from 'the land of schoolmasters and leather pumpkin seed.' Poor fellow!—far gone in consumption, had a field of usefulness been open to him, he could not have labored in it. He went to sea for his health, but never returned. There was no schoolmaster in the next ship, and the 'young gentlemen' were as expert at lunars and as au fait in the mysteries of latitude and departure, as any I had seen. In my next ship, the dominie was a young man, troubled like some of your correspondents, Mr. Editor, with cacoethes scribendi. He wrote a book. But I never saw him teaching 'the young idea,' or instructing the young gentlemen in the art of plain sailing; nor did I think it his fault, for he had neither schoolroom nor pupil. Such is my experience of the school system in the Navy; and I believe that of every officer will tally with it."18

Schoolmaster George Jones, of the good ship Constitution, cruising in the Mediterranean from 1826-28, presents a somewhat brighter picture than Maury's. He says that his school "was placed by Captain Patterson under excellent regulations; a room on one side of the half deck was screened off for us; I had the morning, and the Spanish teacher the afternoon; those who were on my list attended from necessity; many of the rest from choice; and in a short time study was 'all the go' through the steerage, extending itself also into the wardrobe. The cobwebs were soon brushed from their brains, and a more diligent, and I may add successful, set of pupils will no where be found, than in a few weeks were those of our ship. Thus it continued through the summer, much to my gratification, and to the admiration of all who came on board. I placed before them the following course of study: 'the day's work (Bowditch); Bowditch, in course; algebra (Day or Riddle); geometry (Riddle or parts of Playfair's Euclid); plane trigonometry; analytical trigonometry (the elementary principles of Riddle); spherical trigonometry (Riddle); investigation of the rules and principles of lunar and other observations (Riddle). It is a pretty thorough course; they took it up with ardor, and some have completed it; most had advanced considerably before winter; but winter was fatal to our school. Our exposed room became uncomfortable; I tried to get another, but could not succeed, and the school was removed to the steerage, where I could exercise no authority, as it was in a private room, and where, amid the noises and confusion of such a place, the spirit of study by degrees evaporated."19

From provision for schools on shipboard, it was but a short step to their establishment in the principal navy-yards, where a considerable number of midshipmen were usually on duty. The facilities in the navy-yards for conducting a school were a little better, but the improvement was by no means great. The schoolroom was on board a ship in ordinary, or a receiving ship, or in some building of the navy-yard. The students, being subject to duty either in the yard or on ships temporarily stationed in port, were irregular in their attendance. To other distractions was added that of recreation on shore. Moreover, a midshipman's school-work was liable to be brought to a close any day by an order to join a ship and proceed to sea. When officers were required, the department gave little or no heed to the needs of the schools and their pupils. The number of teachers at the navy-yard schools varied from one to three, and the number of pupils as a rule from five to thirty. The same branches of study were taught as in the schools on shipboard at sea.

The earliest navy-yard school of which I have found a record was established at the Washington yard about 1807. It was at first conducted by Chaplain Robert Thompson "for the purpose of instructing the young gentlemen of the Navy in the theory of navigation." From 1811 to 1814, it was in charge of the Reverend Andrew Hunter, one of the most noted of the early naval chaplains, and a man of much ability and of high character. He had served as a chaplain in the Army of the Revolution, and later as a professor of mathematics and astronomy at Princeton. He owed his appointment to a chaplaincy largely to his abilities as a mathematician. His official title is sometimes given as "chaplain and mathematician in the Navy."

In 1811 when entering upon his duties at the Washington navy-yard, the Reverend Andrew Hunter, at the request of Secretary of the Navy Hamilton, drew up a course of studies to be pursued by the midshipmen and junior officers. This embraced arithmetic, geometry, trigonometry, logarithms, astronomy, navigation, "geography and the use of the globes," English, a "short course of history and chronology, together with some parts of natural philosophy, particularly mechanics, hydraulics, and some selections of chymistry and electricity." "The time which might be deemed necessary for relaxation from ardent studies," Hunter wrote in blissful ignorance of the recreative tastes and needs of the old-time midshipmen, "might be employed in more extended historical reading and biographical research." He conceived that many useful and ornamental acquirements might be added to those already enumerated. Hunter's school, while a most excellent one, naturally fell short of his high standard.20

The war with Great Britain greatly swelled the list of midshipmen of the Navy, and not a few of them received instruction at the Washington navy-yard. Writing to Secretary of the Navy Jones in 1813, Hunter said that, since he entered upon his duties, he had had more than one hundred midshipmen under his tuition, whom he had "endeavored to instruct not only in the theory of their profession, but in such collateral studies as would prepare them for such an appearance and reception in genteel society as would give them influence and reflect honor upon their corps. My pride was that they should be not only mechanical, but scientific, seamen." Unfortunately, some of the young gentlemen did not appreciate their teacher's zealous and painstaking labors in their behalf. They "seemed to spurn what was said with regard to the necessity of their scientific improvement, and supposed that they could acquire a kind of mechanical knowledge by inspection of gunter's scale, or some other way not at all to be depended upon. If they should ever have the command of a ship, Divine Providence or somebody wiser than themselves must direct the helm or the ship and crew will go to ruin."21

In October, 1814, Commodore Isaac Chauncey, who was in command of the American naval forces on the Great Lakes, established a mathematical school at Sacketts Harbor, on Lake Ontario, under the direction of his chaplain, the Reverend Cheever Felch. It was continued until March, 1815. A letter of Felch to Captain J. D. Elliott, dated December 6, 1814, gives some notion of the character of the chaplain and his work: "My school goes on finely. About 100 officers attend; a number of Lieutenants. I have removed the officers into another room, and have nearly 100 ship's boys in that room. Government ought certainly to make me some compensation for this extra service. I do the duty of eight chaplains. Should time, opportunity, circumstances, etc., favor, you would confer a great obligation on me by sounding the Secretary on the subject." Later, Felch began the preparation of a "System of Studies for Midshipmen," which, however, he was unable to complete, and for which he received several hundred, or possibly a few thousand, dollars.22

After the War of 1812 the navy-yards on the seacoast became important manufactories and depots of supplies, and schools were established at several of them, usually on board ships in ordinary. The first of these wag organized at the Boston yard in January, 1816, by Chaplain Felch.23 In September of that year it was attended by forty-three junior officers from the ships Independence, Congress and Macedonian and from the Boston navy-yard. In 1821 Chaplain David P. Adams started a school at Norfolk. By February, 1822, four navy-yard schools had been established—at Boston, New York, Philadelphia, and Norfolk—which flourished intermittently. In 1824 the New York school was prospering under the tuition of Chaplain Cave Jones. There is some evidence that Jones and Secretary of the Navy Southard regarded this school as the commencement of the naval academy that Southard wished to establish on Governor's Island. From 1827-39 the two principal schools were those at New York and Norfolk. Their chief duty was the preparation of midshipmen for examination to the grade of passed midshipmen. For a time the New York school was held in the loft of one of the ship-houses at the navy-yard; and the Norfolk school, on board the frigate Java. In 1833 the latter was commanded by Farragut. In January, 1838, there were two teachers and twenty-six students at the New York school; two teachers and four students at the Norfolk school; and one teacher and two students at the Boston school.24

A board of naval officers met once a year to examine midshipmen for promotion. For several years its meetings were held. in a parlor of Barnum's Hotel, in Baltimore. A professor of mathematics of the Navy often conducted the examinations in mathematics. The line officers always asked the questions in navigation and seamanship. How unique were the examinations of these ancient mariners, Mr. Park Benjamin's bright and breezy pages on the Naval Academy make clear. The midshipmen passed through the ordeal before the board with fear and trembling. Rear-Admiral B. F. Sands has described his experiences in 1834 when sixty-seven midshipmen came up for promotion: The young men were called in one at a time "from the ante-room, which always had some dozen or so `expectants' in waiting, the names of those who were likely to be called being ascertained the evening before. Other stragglers assembled around the barroom below, awaiting to congratulate the successful or to condole with the unfortunate through the medium of a mint-julep treat by those who joined smilingly as they came from the tribunal. I remember when I came out from the board-room my clothes were damp with perspiration, such was the degree of excitement through which I had gone."25

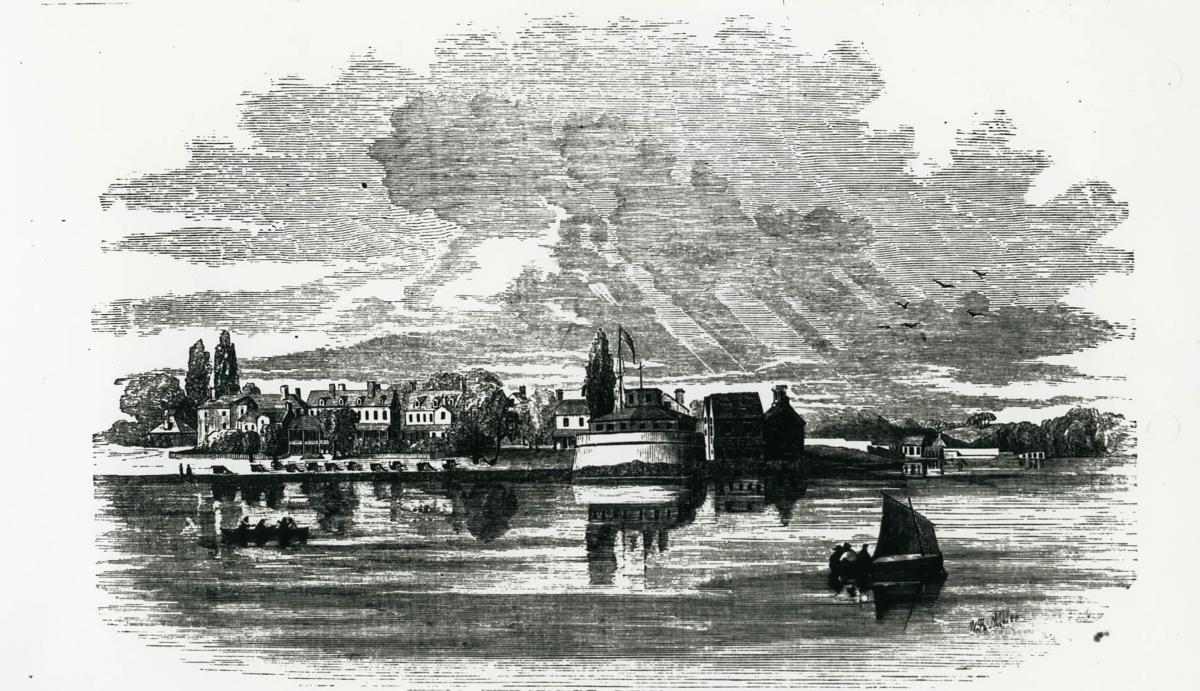

The inefficient work of the navy-yard schools, especially in preparing the midshipmen for their examination for promotion, led in 1839 to a most important advance in naval education. Credit for this must be given to Secretary of the Navy James K. Paulding, Commodore James Biddle, and Professor James McClure, and possibly to Chaplain George Jones. In 1839 Biddle was president of the board of examiners, and also governor of the Naval Asylum, a retreat for aged and decrepit seamen which had been recently established at Philadelphia. In the first half of 1839 he suggested to Paulding that the examining board for that year should meet at the asylum, and that a naval school should be established there for the purpose of preparing midshipmen for their future examinations. Biddle evidently desired to correlate the work of the examining board with that of the naval school. He wished to provide a better location for a school than had been found at the navy-yards, and to obtain a more effective control over the students than had hitherto been possible. He thought it was best to make a "very humble beginning," with a single professor to prepare the midshipmen for their examinations in navigation and mathematics. When once the school is clearly under way, he wrote to Paulding, it can be enlarged, both as to the number of students and the branches to be taught, to any extent that you may wish. His plan provided for the discontinuance of the schools at the navy-yards and the concentration of all the educational work of the navy on shore at the Naval Asylum.26

Biddle's efforts in behalf of a naval school were re-enforced by those of Professor David McClure, of Philadelphia, a wellknown teacher and scientist of that city. In the spring of 1839, McClure, who had been recently disappointed in not obtaining the vice-presidency of Girard College, solicited Secretary Paulding for an appointment to the navy as a professor of mathematics, and urged him to establish a naval academy at Philadelphia, in which McClure hoped to be employed. He discussed these subjects with Paulding while on a visit to Washington.27 In June McClure received the appointment of professor of mathematics, and in July, at the suggestion of Biddle, he began to prepare a course of studies and some lectures for the proposed school.

Not until near the close of 1839 was the new institution in operation. On November 15, Paulding ordered fifteen midshipmen and Professor McClure to report to Biddle at the "Naval School about to be established at the Naval Asylum." Twenty-four rooms in the basement of the asylum were given up to the midshipmen, who were at first required to room in the building. These quarters proved to be, in the words of a report, "damp, cold, cheerless, and unhealthy." Later, largely through the efforts of Lieutenant A. H. Foote, more comfortable rooms were assigned the young gentlemen on one of the upper floors. In the end most of the midshipmen were permitted to find quarters in the city. From time to time Biddle issued regulations for his school. The hours of instruction were fixed from 9 A. M. to 2 P. M. McClure was to report monthly on the progress and merits of his students. These reports together with an annual report of Biddle were to be laid before the examining board, which in the future was to meet at the asylum. The attendance of the midshipmen at chapel on Sunday was required. They were forbidden to play cards. The lights in their rooms were to be out by 9 P. M. They could not leave the grounds without permission.28

The attempts of Biddle and his successors to subject the midshipmen to a scholastic regimen were not wholly successful. They did not take kindly to "Biddle's Nursery," as they called the new establishment. When the monotony and routine became duller than they could well bear, they sought enlivenment in quarrels among themselves or with the populace of the city. The Philadelphia Daily Chronicle of November 12, 1842, informs us that a "Gentleman was stabbed last evening at the menagerie, corner of Thirteenth and Spruce Streets, by a young midshipman. The wound, it is feared, will prove fatal." Fortunately, the injury was slight. In the days when midshipmen fought duels on the least provocation, they did not permit the rules of the Naval School to interfere with these gentlemanly exercises. A brief account of a breach of this sort is given in a letter of the governor of the Naval Asylum to the Secretary of the Navy, dated October 23, 1842: "On the 20th instant Midshipman Knapp left the Asylum without permission, and yesterday morning fought a duel with Midshipman Rhind at Burlington, in which he received a wound in the face just below the upper cheek bone, which is said to be severe but not dangerous. Midshipmen Downes and Guest accompanied Midshipman Knapp on the ground, the former as second, the latter as a friend in case of need, both of these officers left the Asylum without leave. I have therefore ordered their liberty to be stopped until the decision of the Department is made known to me."29

In February, 1842, the Naval School was closed, owing to an epidemic of small-pox. In April it was opened again, under new auspices. Commodore James Barron had succeeded Biddle as Governor of the asylum and superintendent of the school, and William Chauvenet had taken the place of McClure as professor of mathematics. The coming of Chauvenet, a brilliant young teacher and mathematician, began a new era in the history of the school. He at once improved its instrumental equipment and library, which he found very deficient. He prescribed a more rigorous course of studies in mathematics, and introduced new textbooks, having found Bowditch too elementary. In 1843 a fixed course of study, beginning in the fall and continuing for a scholastic year, was at his suggestion approved by Secretary of the Navy Henshaw.30 A teacher of French had been added in 1840.

In January, 1844, Chauvenet drew up a curriculum, covering two years' work, and including courses in algebra, geometry, plane and spherical trigonometry, navigation, nautical astronomy, nautical surveying, "mechanics and the steam engine," drawing, gunnery, naval tactics, the French and Spanish languages, naval history, and maritime law. The students were to spend their summers on practice cruises. Entrance to the school was to be upon examination. Seven teachers were to give instruction. On January 25, 1844, the new plan was approved by Secretary Henshaw.31 In accordance with it, in March he ordered Lieutenant J. H. Ward to the Naval School to give a course of lectures on ordnance and gunnery. Ward's lectures were delivered in April and May, 1844, and early in 1845 they were printed. This book is the first of a considerable number of valuable works treating of technical and professional subjects, which have been published by the officers and professors of the Naval Academy.

New Secretaries of the Navy often exhibit toward the work of their predecessors a fatuous ignorance. They have an itch to change something, no matter what. Often they fall foul of a new set of advisers. No better illustration of these facts can be found than the order of Secretary of the Navy Mason of September 9, 1844, which revoked Henshaw's order of the previous January approving Chauvenet's course of study.32 Mason justified his action on the ground that the midshipmen could not be spared two years from sea. He, however, did not entirely abandon Chauvenet's plan, for he considerably increased the number of teachers at the Naval School. In April, 1845, these comprised William Chauvenet, instructor in mathematics; Julius Meire, instructor in French and Spanish; J. H. Belcher, instructor in international law; H. H. Lockwood, instructor in pyrotechnics; and William F. Mercier, assistant to Lieutenant Ward in ordnance and gunnery. The first four men were professors of mathematics in the Navy, and Mercier was a third assistant engineer. Ward may be considered a member of the faculty, although not in residence. Late in the spring of 1845 Passed Midshipman Samuel Marcy was ordered to the Naval School as the assistant of Chauvenet in mathematics. In April, the number of midshipmen in attendance was forty-six.

It is evident that, as compared with the schools at sea and at the navy-yards, the Naval School at Philadelphia marks a distinct advance. A considerable step had been taken toward the establishment of a naval academy. The new school went far toward consolidating the work of naval instruction on shore, and it correlated the work of instruction with that of the examining board of midshipmen for promotion. In faculty, curriculum, discipline, and location, it was a decided improvement over all previous naval schools. In the fall of this year, 1845, George Bancroft, then Secretary of the Navy, upon the recommendation of a board of officers, moved the school to Fort Severn at Annapolis. There, in 1850, it received its present name, United States Naval Academy.

1. C. H. Lincoln, Calendar of John Paul Jones Manuscripts in the Library of Congress, p. 20.

2. J. C. Hamilton, Works of Alexander Hamilton, VI, 295; H. C. Lodge, Works of Alexander Hamilton, VI, 265-272.

3. Am. State Papers, Mil. Aff., I, 333-134, 228; Works of John Adams, IX, 65.

4. Am. State Papers, Nay. Aff., I, 323, 356-359.

5. J. R. Soley, Historical Sketch of the United States Naval Academy, 27-31.

6. Richardson's Messages and Papers of the Presidents, II, 390.

7. Register of Debates in Congress, II, 1053-1036.

8. J. R. Soley, Historical Sketch of the United States Naval Academy, 21-22; Register of Debates in Congress, III, 348-376, 501, 506-524, 1365, 1500; Journals of the House of Representatives, March I, 1827.

9. Congress Letters, VIII, 349, 379, 452, 454; Congressional Globe, XI, 858-860, 864, 888, 961.

10. Congressional Globe, XII, 84-85; XIII, 176; XIV, 128; Senate Docs., 28 Cong., 2 sess., no. 92.

11. Regulations and Instructions relating to His Majesty's Service at Sea, quoted in Soley's Naval Academy, 9.

12. General Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., III, 526; Works of John Adams, IX, 65.

13. U. S. Statutes at Large, II, 789.

14. Rules of Navy Department Regulating the Civil Administration of the Navy (1832), p. 38; U. S. Statutes at Large, IV, 756.

15. Russell Jarvis, Commodore Elliott, 232-233.

16. Quoted in Soley's Naval Academy, 8-9.

17. Officers' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., Nov., 1831, no. 84.

18. Southern Literary Messenger, VI, 315.

19. George Jones, Sketches of Naval Life, II, 261-262.

20. Captains' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., 1807, I, no. 54; Officers' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., V, no. 29; XVI, no. 22r.

21. Officers' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., XVIII, no. 261; Miscl. Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., LV, no. 116.

22. Officers' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., XXXIII, no. 138; LXV, no. 27; Letters to Officers of Ships of War, Navy Dept. Arch., XIV, 254.

23. Officers' Letters, XXXIV, no. 126; XXXVI, no. 166; LXV, no. 27.

24. U. S. Navy Register for 1838.

25. Park Benjamin, United States Naval Academy, 114-118; B. F. Sands, From Reefer to Rear-Admiral, 78.

26. Letters to Officers of Ships of War, Navy Dept. Arch., XXVII, no. 106; Captains' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., March, 1839, no. 68; July, 1839, no. 45.

27. Philadelphia Inquirer, June 22, 1882.

28. Letters to Officers of Ships of War, Navy Dept. Arch., XXVIII, 144; Shippen, Origin of the Naval Asylum, 138; Daniel Ammen, The Old Navy and the New, 94-98; Captains' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., Feb. 1840, no. 14.

29. Captains' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., Oct. 2842, no. 280.

30. Officers' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., Aug. 1843, no. 67; Oct. 1843, no. 80.

31 Officers' Letters, Navy Dept. Arch., Jan. 1844, no. 202; Letters to Officers of Ships of War, Navy Dept. Arch., XXXVI, 219.

32 Letters to Officers of Ships of War, Navy Dept. Arch., XXXVII, no. 367.