Keeping an accurate record of weather conditions has long been a part of a naval officer’s duties. In the era before accurate charts were widely available, wind and weather records provided important information to aid navigation. Mariner’s guides—sometimes known as rutters—from the earliest times are full of records of such information.

Naval officers in the Age of Sail were expected to keep a private log of the changing weather as well as contribute to the ship’s official one. Among other things, these important documents could provide crucial evidence at a court-martial or official inquiry. In the 18th century, a Royal Navy officer who captured an enemy warship was expected to submit a full report to the Admiralty on his prize’s sailing characteristics in various conditions. But this was an era before anemometers and other modern devices for measuring wind speed. The result was that officers used a variety of subjective and often esoteric descriptives. One sailor might record the conditions as “blowing above a cap full of wind,” while to another it was merely a “stiff breeze.” What was required was a commonly understood scale of wind speed, and the Royal Navy’s Rear Admiral Sir Francis Beaufort was determined to supply it.

Beaufort was born in Ireland in 1774. His father—a Protestant clergyman and a member of the Royal Irish Academy—published the remarkably detailed “New map of Ireland, civil and ecclesiastical” in 1792. He passed his keen interest in mathematics and cartography to his son.

Beaufort first went to sea at 15, serving on board an East Indiaman as an apprentice officer on a trading and surveying voyage to Indonesia. During this voyage, his ship was wrecked because of a navigation error caused by an inaccurate chart. The experience would shape much of his later life.

Two years later and back in Britain, Beaufort joined the Royal Navy. He had an active career, serving mainly in the Channel Fleet. He saw action as a midshipman on board HMS Aquilon during Admiral Richard Lord Howe’s victory on the Glorious First of June and was badly wounded as a lieutenant on the frigate HMS Phaeton while leading a cutting-out operation on the Spanish coast.

While Beaufort’s career was steady rather than spectacular, it was not for his military exploits that he gained his reputation. From the start of his naval career, he was always known as a scientific-minded officer. Even as a midshipman, he kept a meticulous record of the weather and tides and showed exceptional promise in navigation and map-making. In advance of Britain’s abortive attack on Buenos Aires in 1807, as a commander, Beaufort made a careful survey of the Rio de la Plata to provide the expedition with accurate charts.

When he was made post captain in 1810, he was given command of HMS Frederickstein and sent on an expedition to the Mediterranean both to map the coastline of southern Turkey and to suppress piracy in the area. Beaufort returned with a full set of highly accurate charts—and a nasty wound from a pirate bullet in the hip.

By the end of the Napoleonic Wars, Beaufort’s reputation as an exceptional cartographer was established. When he retired from active service in 1829, Beaufort was made Hydrographer of the Navy, a post he held until he was 80 years old and for which service he was eventually promoted to rear admiral. In that time, his department transformed the accuracy of ocean surveying, producing high-quality charts for the maritime community. Thanks to his leadership, this work undoubtedly saved thousands of sailors’ lives. He also became a major part of the scientific community, encouraging voyages of exploration such as the polar expeditions of Sir John Franklin, and he helped found institutions such as University College, London, and the Royal Geographical Society.

It was during this period that Beaufort finalized the scale of wind strength that bears his name. He was not the first to come up with this concept. As early as 1703, Daniel Defoe had published a Table of Degrees, a 12-point scale that went from 1–“Stark Calm” to 12 –“A Tempest.” But Defoe’s and other previous scales were still subjective, relying on the opinion of the observer. Beaufort wanted to find common and objective definitions all could share. Without any way of recording the actual wind speed, he looked for something readily available to act as a proxy. Perhaps unsurprisingly for a Royal Navy officer who had stood long watches on frigates, he lighted on a ship’s sails. The moment at which a gale became a storm might be subjective, but the point at which a ship had to take in sail was not.

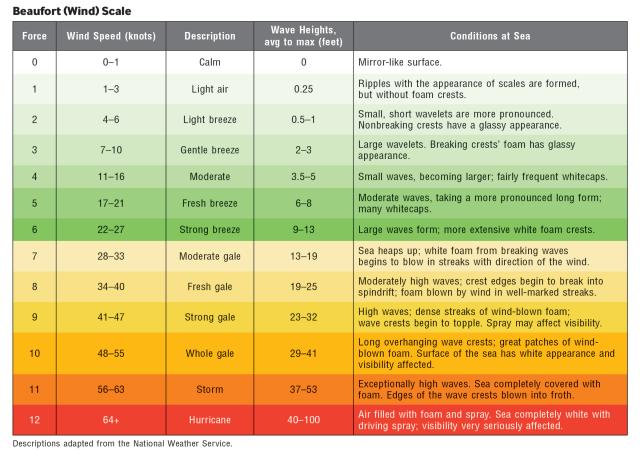

First drafts of his scale can be found in one of his logbooks from 1805, and Beaufort continued to refine the idea over the years. His final version also used a 12-point scale like Defoe’s but with concrete examples. Force 0–“No wind” was present when “the ship [was] becalmed.” Force 12 –“A hurricane” existed in the presence of a wind “to which a ship could show no canvas.” Between the two extremes were various stages. Force 5–“Fresh breeze” could be identified when the ship “could just carry royals close hauled,” while Force 9–“Strong gale” was present when sail had to be reduced to “close-reefs and courses.”

The Royal Navy adopted the scale in the 1830s, with all ships instructed to log wind conditions hourly using the scale. The new Beaufort Scale was sent out with instructions to all commanders that “a copy shall be pasted into each book and painted on the back of each log board.”

While Beaufort’s scale was an undoubted improvement on what had come before, it was not without issues. For one thing, it was specific to square-rigged warships and therefore not applicable to different sailing rigs or smaller vessels. For another, Beaufort’s period as Hydrographer of the Navy overlapped with the adoption of steam power, bringing the prospect of ships without sails at all. He needed to find a new gauge of wind strength that used a different, more universal measure.

His attention moved from sails to the way the appearance of the open sea changes with the wind. Retaining the structure of the original scale, he revised the definitions. Calm became “a mirror-like sea,” while a Force 12 hurricane produced “air filled with foam and spray and a sea completely white.” Between the two were all the various sea states, producing today’s familiar scale. Beaufort died before his revised scale of wind force was published in 1874, but it was named in his honor. In 1903, it was republished with measured wind speeds added, as well as additional forces beyond 12. It still retained his name and his sea states, as it does to this day.

Although he is best remembered for his wind scale, Beaufort’s greatest contribution to science is the one for which he is least known. As Commander Robert Fitzroy planned his second expedition in HMS Beagle, he asked Beaufort to recommend a gentleman naturalist. Beaufort suggested the young Charles Darwin, whose mind was set to pondering by the sheer variety of animals and plants he observed on that voyage.