In September 1782, the French 38-gun frigate Hébé was escorting a small convoy along the Brittany coast toward the naval base at Brest when an unknown sail was spotted. It proved to belong to HMS Rainbow, a Royal Navy frigate of similar size to the Hébé, under the command of Captain Henry Trollope. The French ship stood out to intercept and was the first to open fire. Her opponent remained ominously silent, maneuvering to close the range, which took more than an hour. When Trollope finally got the Hébé close alongside, he fired a broadside of such ferocity that it brought down the Hébé’s foremast, wounded her captain, and prompted him to surrender. The French ship had just encountered an enemy armed exclusively with British General Robert Melville’s new naval weapon: the carronade.

Melville was an artillery officer with a keen interest in scientific improvement. In the 1750s, he began to investigate means for merchant ships to protect themselves from attack by privateers or pirates. A standard ship’s cannon was a large piece of ordnance, often weighing several tons. It required a substantial crew to operate, plenty of room for its powerful recoil, and strong ship’s timbers to absorb the shock of its discharge. Unfortunately, none of this could be supplied on board most merchant ships with their small crews, cluttered decks, and weaker construction. Melville’s solution was to completely redesign naval cannon to operate within these constraints.

He first reduced a gun’s weight by giving it a much shorter barrel. This drastically reduced its effective range, but he saw this as a minor disadvantage. The weapon he envisaged would only need to fire on an attacker trying to come alongside, and he soon realized that his weapon’s short barrel produced other benefits.

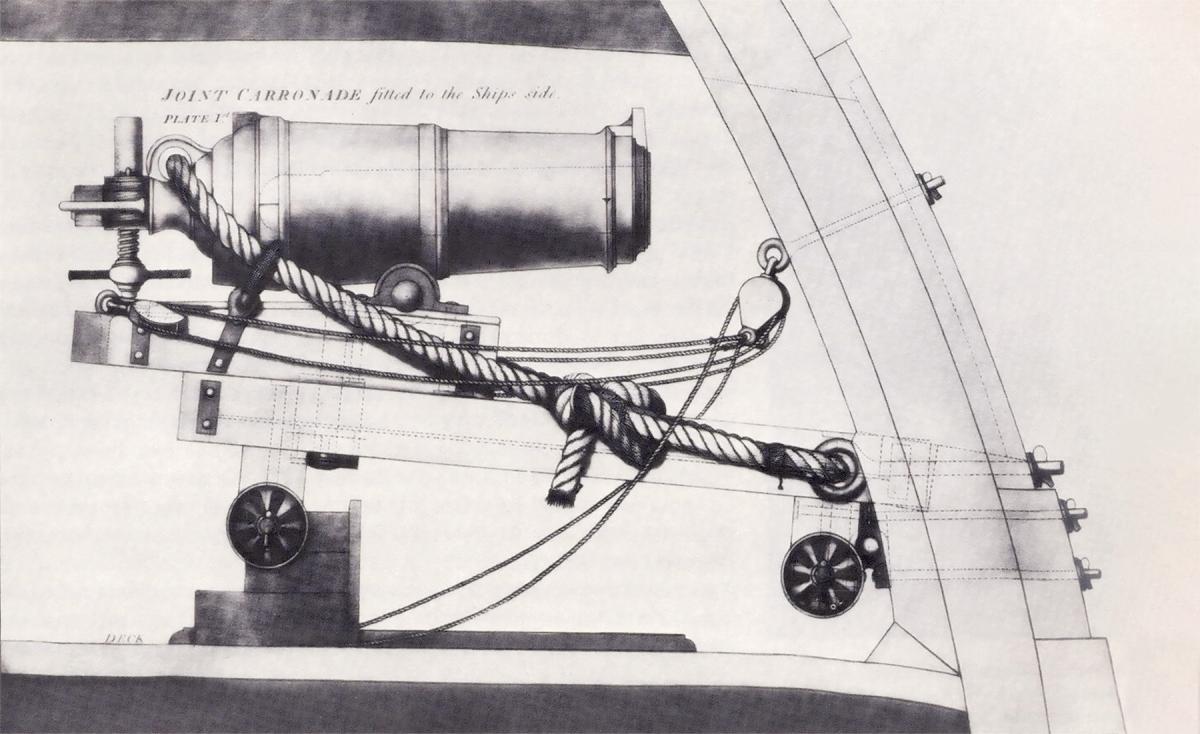

The gun’s short range meant it required only a third of the usual powder charge for the same size ball. In turn, using a smaller charge allowed a barrel cast with thinner walls to contain the reduced blast, saving yet more weight. And a reduced charge produced a gentler recoil. Not only did this mean that firing it was unlikely to damage a ship’s timbers, but it also allowed the new weapon to be mounted on a slide, instead of a traditional gun carriage. Operating it therefore took up much less space, and it required only a small crew because there was no need to run up a heavy gun on a wheeled carriage. A slide also permitted a wider field of fire, an important feature for a civilian ship wanting to engage an enemy overhauling it from astern.

Melville worked on his design with an engineer named Charles Gascoigne. Gascoigne managed the Carron Company ironworks in Falkirk, Scotland, and he had been working on his own light cannon for merchant ships. In 1776, the finalized design went into production. Melville referred to their combined invention as a “smasher,” but the weapon came to be named “carronade” after the foundry. Early demand was limited, with the guns fitted only to merchantmen sailing in waters with a strong risk of pirate attack, such as the Indian Ocean and the Barbary Coast. But their popularity among shipowners grew quickly during the American Revolution, when an overstretched Royal Navy struggled to protect Britain’s extensive commerce from American and French privateers. It also brought the new weapon to the attention of the British Admiralty.

At the heart of the Royal Navy’s interest in carronades was a paradox between how traditional cannon were intended to be used and how they were deployed in practice. Ships’ long guns could throw a ball with reasonable accuracy up to a mile. But this was a capability most British captains rarely employed. Their preferred tactic was to engage an opponent at short range, firing quickly into the hull, until victory was achieved. In these circumstances, rate of fire and weight of metal were much more important than long-range accuracy. Carronades scored well by both measures. Not only could they be fired more quickly than long guns, but a carronade of the same overall weight as a cannon also could fire a much heavier ball.

The Royal Navy placed orders for carronades of several different sizes and carried out trials. Following the success of these, HMS Rainbow, an old frigate approaching the end of her useful life, was equipped with the new weapon as an experiment. In place of the long 18-pounder cannons she previously carried on her main deck, she bore huge 68-pounder carronades, while on her quarterdeck and bow she mounted 42-pounder “smashers.” This increased her broadside weight by more than four times. It was this that won Captain Trollope such a swift victory.

Following the capture of the Hébé, the Royal Navy began to deploy carronades across the fleet. On larger warships, they were mounted on the upper decks to replace the small cannon traditionally carried there. A typical change was made to the 38-gun frigate Diana, for example, when she underwent a refit in 1796. The 9-pounder guns on her quarterdeck and forecastle were replaced by 32-pounder carronades that weighed the same as the long guns. Early encounters with the enemy showed the benefit of such upgrades, and, by 1800, apart from specialist long-range chase guns, most upper-deck cannon had been replaced throughout the fleet.

After several encounters with carronade-armed Royal Navy ships, other navies began to develop versions of the new weapon. But this took time, and for much of the American Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars, they were more prevalent in the Royal Navy. Carronades helped give the British a distinct advantage in close-range encounters. When HMS Victory passed astern of the French Bucentaure at the Battle of Trafalgar, the 68-pounder carronades on her forecastle fired canister rounds, each containing more than 500 musket balls, along her opponent’s gun deck.

The U.S. Navy enthusiastically embraced carronades. The first American manufacturer was the Eagle Foundry in Philadelphia, which began production around 1799. The guns went on to form an important part of the armament of U.S. warships and contributed to the Navy’s successes in the War of 1812. U.S. frigates such as the Constitution combined 24-pounder long guns on their main deck with a full battery of 32-pounder carronades mounted on the spar deck above.

Carronades were highly effective in the right circumstances, but their downsides were sometimes overlooked. In particular, their limited effective range meant that ships overly reliant on the weapon could be defeated by cannon-armed opponents that kept their distance. This was the fate suffered by the U.S. Navy’s frigate Essex during the War of 1812. Armed almost exclusively with 32-pounder carronades, she was sent into the Pacific under the command of Captain David Porter to attack British whalers. After a highly successful campaign, she fought the Royal Navy frigate HMS Phoebe, commanded by Captain James Hilyar, off the coast of Chile in 1813. The ships were of similar size, and each had a sloop in support, but the decisive difference was that the Phoebe had a main battery of 18-pounder cannon. The Essex had lost her topmast in a squall, which made her slower and less maneuverable than her opponent, which skillfully kept out of carronade range while battering the Essex into submission.

Despite their effectiveness, the age of the carronade was short-lived. No sooner had they become widespread than the quickening pace of gunnery development made both them and the smoothbore cannon redundant. In the 1820s, the French artillery General Henri-Joseph Paixhans developed an exploding shell for warships that replaced traditional solid cannonballs. This, combined with the introduction of rifling, extended the range at which future naval actions would be fought far beyond the reach of the smashers.