Up the Arkansas River some 125 meandering miles from its junction with the Mississippi River and far from oceans is the home of a U.S. Navy icon, one of only two surviving ships from the 7 December 1941 surprise attack on Pearl Harbor. The yard tug Hoga (YT-146) does not have the name recognition of the battleships that were the focus of Japanese bombers and torpedo planes. But while the battleships fought the enemy, the Hoga fought the effects of the Japanese strike.

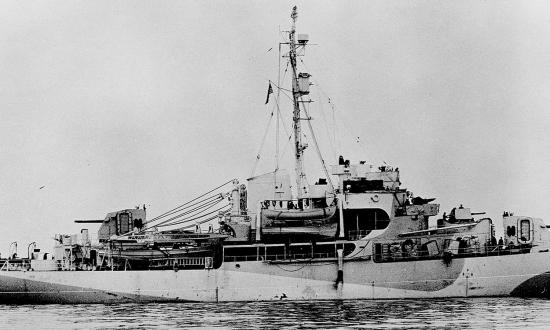

The little tug was virtually new at the time of the attack. She had been laid down on 25 July 1940 at the Consolidated Shipbuilding Corporation in the West Bronx and launched into the Harlem River on 31 December from Morris Heights, New York. She was delivered to the Navy on 22 May 1941 at Norfolk, Virginia, and assigned to the 14th Naval District at Pearl Harbor. The tug made the voyage there by way of the Panama Canal and Naval Base San Pedro, California.

As typical of yard craft, there was little excitement in her daily chores of shuttling about cargo lighters and pushing and pulling warships into and out of their berths.

On the morning of 7 December, the Hoga was moored with other service craft in the Southeast Loch near 1010 Dock. Battleship Row along the South Channel was readily visible across the Turning Basin. The Hoga’s tugmaster, Chief Boatswain’s Mate Joseph B. McManus, was shaving when he heard the first explosions. “I heard the noise and I looked out the porthole . . . and the first sight I saw was the Oklahoma [BB-37], which had quite a list. She had been hit. . . . The Chief Engineer was standing on the dock and I heard him say, ‘My God! This is war!’”

McManus soon received a cryptic message: Get under way and assist wherever you can.

Within ten minutes, the Hoga was steaming toward Battleship Row. Along the way, she rescued two sailors. The tug first headed for the repair ship Vestal (AR-4), moored alongside the doomed Arizona (BB-39). The battleship had already suffered a massive explosion, and huge fires engulfed her remains. The blast had cleared the nearby repair ship’s topside of crew, including her commanding officer, Commander Cassin Young. He swam back to the ship, countermanded an order to abandon ship, and ordered, “Lads, we’re getting this ship underway.” As the Vestal, having suffered two bomb hits and on fire amidships, began to move, steering by engines alone, the Hoga pulled her bow away from the Arizona. Tugmaster McManus had served on board the Vestal just a few months prior.

The Hoga next moved back across the basin to 1010 Dock and the sinking flagship of Minecraft, Battle Force, the minelayer Oglala (CM-4). Fortunately for the ship, her shallow draft allowed her to escape a Japanese torpedo, but it slammed into the Helena (CL-50) moored alongside. Unfortunately for the Oglala, the explosion ruptured her seams. Next, a bomb exploded between the two, causing even greater damage and exacerbating the Oglala’s ever-increasing list to port. With the minelayer threatening to capsize and lock the cruiser against the dock, the Hoga, with help from harbor tug YT-130, pulled the Oglala aft and clear of the Helena.

In the meantime, the battleship Nevada (BB-36) had gotten up steam and was making a run for the ocean. She became the focus of attacking aircraft crews, who saw the possibility of not only sinking a battleship but, if they could put her down in the narrow channel, also bottling up the harbor for a very long time.

Despite his own flagship, the Oglala, being on the verge of sinking, Rear Admiral William Rea Furlong sent the Hoga and YT-130 to the aid of the battleship to “help nose the Nevada over toward Hospital Point” and out of the channel. The two tugs freed her from the mud and moved her to the western side of the harbor entrance, where the battleship finally settled clear of harbor traffic. The Hoga, which was equipped with firefighting monitors (water cannon), as were all yard tugs, attacked the fires raging in the Nevada’s forward section. Lashed to the battleship’s port bow, she fought the fires with her pilothouse monitor and four hose lines for more than an hour.

As other ships came to assist the Nevada, the Hoga moved back to Battleship Row. She worked her way east, attacking the fires raging on board two ships trapped between outer-row battleships and Ford Island: the Maryland (BB-46), next to the overturned Oklahoma, and then the Tennessee (BB-43), alongside the sunken West Virginia (BB-48). By 1600, the Hoga had made it back to the Arizona. She fought her fires until 1300 on 9 December. Assistant Tugmaster Robert Brown later noted: “We didn’t recover any bodies. We were not in a position to do that. We had more important work to do.”

The Hoga continued her efforts through Wednesday morning, recording 72 hours of continuous firefighting. Through the rest of the week, she and her crew cleared debris, patrolled the harbor, recovered bodies, and searched for Japanese midget submarines believed to have gained entrance to the harbor. She also aided in the massive recovery and salvage efforts that continued virtually throughout the war. For their efforts, the Hoga and McManus received a letter of commendation from Admiral Chester A. Nimitz, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Fleet.

The Hoga was redesignated as a yard tug, large (YTB-146) on 15 May 1944, remaining with the 14th Naval District at Pearl Harbor. In February 1962, she was again redesignated, this time to yard tug, medium (YTM-146).

On 28 May 1948, the Navy had loaned the tug “temporarily” to the Port of Oakland, California, for use as a fireboat. The loan would last 46 years. World War II activity had resulted in Oakland becoming the major U.S. Pacific port, surpassing even San Francisco. Yet, until it received the Hoga, it had no municipal fireboat protection.

The tug had changed little from her 1941 configuration, but at Oakland she received the only major updates of her career, primarily to augment her pumping capacity. As built, a pair of 250-horsepower electric pump motors pushed water to three monitors and two manifolds. In 1948, three 225-horsepower diesel engines and centrifugal pumps were added. This increased her pumping capacity from 4,000 to 10,000 gallons per minute. The number of monitors was increased to seven, with four added to the after deck, and a ring of fog nozzles was installed around the upper deck. Ten additional manifolds were added, making six per side for fire department connections. She also took on board 4,000 feet of fire hose and other firefighting equipment.

The $73,000 reconditioning was completed in July, and the tug entered service that month with a new name, Port of Oakland, which was later changed to City of Oakland. The day after her recommissioning, she fought a fire on board the freighter Hawaiian Rancher. Over her nearly half-century of subsequent service to the Oakland waterfront, she fought numerous shipboard and waterfront fires there and also at the San Francisco waterfront. In October 1984, she battled a fire on board the tanker Puerto Rican, some 11 miles out to sea. The tug was listed as a National Historic Landmark in 1989.

At the end of her firefighting career, the tug was returned to Navy in 1994 and transferred to the Maritime Administration Reserve Fleet at Suisun Bay, some 35 miles northeast of Oakland. In keeping with firefighting tradition, she had been “maintained in excellent condition by her crew of Oakland firefighters.” The firefighters’ pride in their tug included their maintenance of a four-foot-long, six-inch deep dent on her forward port quarter, allegedly the result of her interaction with the Nevada on 7 December.

Sadly, there was little, if any, maintenance in the ghost fleet. Some nine years later, on 28 July 2005, the ex-Hoga was donated to the Arkansas Inland Maritime Museum in North Little Rock on the Arkansas River. But it was another four years before the Navy approved a plan to move the tug, and another six years for her to arrive at her current home on 23 November 2015.