During World War II, four major combatants—Great Britain, Germany, Italy, and Japan—used midget submarines with varying degrees of success. The U.S. Navy considered the type but chose not to build any, opting to study the British program.

Midget submarines, however, became a much more interesting proposition after the war, when in 1949 permanent seacoast fortifications and other coastal defense sites ceased to be part of U.S. policy after 150 years as one of the nation’s prime military missions. The inefficacy of coastal artillery and harbor defenses against sea-borne invasion had been demonstrated in the late war. The primacy of possible coastal attack by air or submarine came to the fore. In 1950, responsibility for a limited harbor defense mission was transferred from the Army to the Navy. The Army’s Coast Artillery Corps and its subordinate Harbor Defense Commands were disbanded.

During the war, midget subs had proven somewhat effective raiders. There were two basic types. One was a traditional-style submarine, carrying weapons either internally or externally and with the crew housed internally. The second was essentially an enlarged torpedo, which carried its crew and weapons externally. These were most widely used by the Italians, who dubbed them “chariots.”

Most prominent among the midgets were the British X and XE classes. The X type was responsible for heavily damaging the German battleship Tirpitz at her anchorage in a Norwegian fjord. Others made a successful attack on a floating drydock also in Norway. One spent three days before the D-Day Normandy invasion taking soil samples, sounding depths, and landing divers for beach reconnaissance on two nights at what became Omaha Beach. Two others acted as navigational beacons during the invasion and sounded depths for the Canadians and British at Sword and Juno.

The somewhat larger XE-class submarines were built for use in the Pacific. They participated in two operations to cut important telephone cables connecting Singapore, Saigon, Hong Kong, and Tokyo. Both missions close to shore near Japanese-held locations were successful. An attack in Singapore Harbor against two Japanese heavy cruisers was partially successful. One of the ships, the Takao, was severely damaged and never sortied again. Both midgets returned safely to their towing submarine.

Japan’s Type A midget submarines are best known for their participation in the Pearl Harbor attack on 7 December 1941. Two of the five boats may have entered the anchorage. One was sunk by the USS Monaghan (DD-354). Inconclusive photographic evidence suggests another torpedoed the West Virginia (BB-48). The midgets also spearheaded an attack in Australia’s Sydney Harbor, sinking a converted ferry.

The primary use of German midgets was on the open sea rather than against harbors. The Type XXVII Seehund was the most successful, sinking nine merchant ships. Their small size and quiet running made Type XXVIIs all but invisible to the Allies’ Asdic and hydrophones. The Italians’ small submarines, however, were perhaps the most successful, with chariots in one attack sinking the British battleships Valiant and Queen Elizabeth and a Norwegian tanker as well as damaging a destroyer. A postwar estimate found they had sunk approximately 150,000 tons of Allied shipping.

The U.S. Navy needed to conduct its own tests to determine the efficacy of midget submarines against harbor defenses and the boats’ offensive capabilities. The same midgets to test defenses also had the potential to attack Soviet subs at their bases. A report to a 1949 submarine officers’ conference addressed the defensive aspect:

The midget submarine promises to be as operationally desirable to the U.S. Navy as it would be to a probable enemy. Inasmuch as the Russians have evinced definite interest in midget submarines it is particularly important that our defensive forces have the opportunity to develop the most effective defenses against such craft. This can only be done if we ourselves possess midget submarines with which to train our defense forces.

Speaking for the Commander, Submarine Forces Atlantic, Commander Raymond H. Bass proposed an “intelligent antisubmarine mine,” a midget boat—of either a fast “pursuit” or slow “ambush” type—positioned near a Soviet harbor. Cost also was a great appeal. The Navy was building three large expensive antisubmarine boats (the SSK Barracuda class). The midget could be a cheaper alternative and hence available in greater numbers.

By 1950 the Bureau of Ships (BuShips) considered construction of two variants: the Type I, displacing 73 tons surfaced and 84 tons submerged, based on Bass’s proposal for a high-speed harbor facility destruction midget with a complete underwater demolition team; and the Type II, displacing about 30 tons and very close to the British X/XE designs. The Type I would be armed with two internal Mk-27 Mod 4 homing torpedoes; the Type II would carry two external charges, i.e., mines.

That year, the fiscal year 1952 shipbuilding program allocated funds for the Type II as SSX-1, known simply as the X-1.

BuShips was not particularly impressed with its own design, so it let a contract to the Engine Division of Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation for an alternate design. The division proposed the use of a closed-cycle diesel that would provide a higher speed and greater endurance than the Navy’s Type II. The diesel would operate normally on the surface; below the surface the engine would get its oxygen from the decomposition of hydrogen peroxide. The Engine Division’s design was accepted.

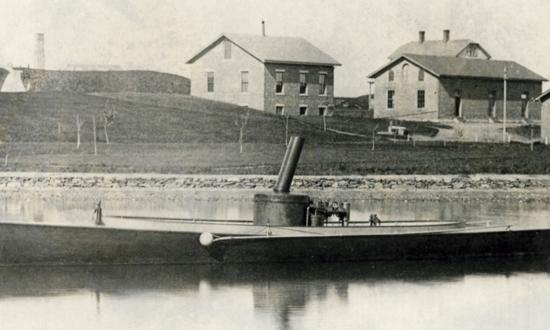

The X-1 owed much to British designs, and two XE-class boats were lent to the Navy for tests: XE7 in 1950 and XE9 in 1952. They primarily were used to evaluate their efficiency in evading harbor defenses. A 1950 report on one such attempt noted: “In those tests the X craft succeeded in going up to the net that had been laid, putting men [swimmers] outside the craft, cutting the net and getting through within 28 minutes under adverse tide conditions. There was no disturbance of the net to amount to anything at all.”

In an 18 September 1950 discussion with the General Board of the Navy, Captain Lawrence R. Daspit, one of the XE test evaluators, stated:

This country has never operated any submarines of this size. . . . We feel that we need a small submarine to evaluate our harbor defenses. . . . A ship of this type, we feel, may succeed in going through the defenses we have today and in mining large units such as carriers or any other valuable ships.

In the same meeting, Commander Bass prophesized, “After the Navy sees what these little craft can do, the demand will be created for their use in many places.”

The X-1 was laid down on 8 June 1954 at Deer Park, Long Island, New York, by the Engine Division of Fairchild Engine and Airplane Corporation. She was launched on 7 September 1955 at Oyster Bay, Long Island, by Jakobson’s Shipyard and delivered to the Navy on 6 October at New London, Connecticut. The X-1 was officially classified as a “submersible service craft” and given the hull number SSX-1. She was not commissioned but “placed in service” on 7 October 1955 with an “officer-in-charge” rather than a commanding officer.

With a crew of four, the X-1 was developed to evaluate her ability to defend harbors against very small submarines. But she also was intended for the offensive. After a larger submarine would tow the boat into a forward area, swimmers would be deployed for sabotage missions against ships in port and other tasks. Two divers could be carried for short durations, for a total of six men. Also, a four-foot section could be installed forward (between the craft’s bow and main hull sections) to carry a single, 1,700-pound XT-20A mine. Although a passive sonar was provided, in reality, the midget had no combat capability.

The power plant proved extremely troublesome. After initial sea trials at New London, the boat entered the Portsmouth Naval Shipyard for further tests. From October through December 1956, three tests of the engine using hydrogen peroxide were conducted. During the first test, determining the proper fuel-to-peroxide ratio was “almost impossible.” The engine stalled, and the damage to the pistons and engine block was progressively worse with each test.

Engine problems continued, and on 20 May 1957, the hydrogen peroxide power supply exploded. The bow section was blown off and sank; because of the pressure hull, the remainder of the boat remained afloat. The X-1 was the only U.S. Navy ship to use the closed-cycle engine. She was rebuilt with a traditional submarine diesel-electric installed. But her service was not for long. She was taken off the active ship list and inactivated in reserve at Philadelphia on 2 December.

Three years later, she was towed to Annapolis, Maryland; reactivated; and attached to Submarine Squadron 6 as a research vessel. While based at the Small Craft Facility of the Severn River Command, she conducted antisubmarine warfare–related studies of the chemical and physical properties of water. She remained active through January 1973. The next month she was inactivated and on 26 April was transferred to the Naval Ship Research and Development Center, also at Annapolis. In July 1974, the midget was released for use as a historical exhibit. She subsequently was placed on display on the grounds of the Naval Station complex, North Severn, near Annapolis, and later moved to the Submarine Force Library & Museum, at Groton, Connecticut, where she remains on exhibit.