Soon after the end of World War II in Europe, hitherto secrets of the fight against Germany became more widely known. One of the major headline-grabbing stories was the revelation on 17 May 1945 “that an enemy man-of-war was boarded and captured [by the U.S. Navy] in a battle on the high seas” for the first time since the War of 1812. The references were to the now well-known seizure of U-505 off the west coast of Africa on 4 June 1944 by an escort carrier task group and the capture of HMS Penguin by the Hornet on 23 March 1815.

The reason for the belated U-boat announcement was that the capture included a top-secret Enigma encoding machine and then-current codes. Had the Germans known of this, their communications encryptions would have changed drastically at a most significant point in the war—the Allies invaded Normandy just two days later.

Lost in the fog of war—but not in American headlines—was another capture that is little remembered and was revealed within weeks of its occurrence and shortly after the story of U-505’s capture.

Late on 15 October 1944 and into the wee hours of the 16th, the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Eastwind (WAG-279) attacked and captured a German freighter, the Externsteine, which was trapped in ice off Greenland’s northeastern coast.

The Eastwind was the second of five Wind-class icebreakers built specifically for Coast Guard operations off Greenland. Later, two additional cutters of the class were built. Their design was completed by the famed Gibbs & Cox company of New York with extremely strong hulls of thick plates with closely spaced frames. The design included a bow propeller to clear the hull from ice and dredge broken ice forward. The vessels were heavily armed, including two twin 5-inch/38-caliber gun mounts, one each fore and aft.

The Eastwind was built quickly over just eight months from being laid down on 23 June 1942 at the Western Pipe & Steel Company in San Pedro, California. The design was so complex that Western was the only company to bid on the project. She was commissioned on 3 June 1944 and assigned to homeport in Boston, Massachusetts. Barely four months later, she was making news off Greenland.

Nearly two weeks before the capture of the German vessel, on 2 October, the Eastwind had launched her Grumman J2F Duck seaplane on a routine reconnaissance mission. The plane spotted a trawler at Little Koldewey, more than two-thirds the way up the Greenland coast. The cutter stood north at full speed. Two days later, after spotting signs of enemy activity and having lost contact with the trawler, the cutter placed a landing force in two waves on the southwest side of Little Koldewey Island. After a trek to the east, they captured a German weather station and its 12-man crew before dawn broke.

News of the seizure broke in the United States just seven days later, on 11 October, with a short United Press article that noted the station was “believed to be the last one in Greenland” and that it was “captured last week.” No other details were reported.

After the capture, the Duck continued its reconnaissance over the next 11 days, but with no results. Late in the day on 15 October, the elusive trawler, well camouflaged, was spotted, locked in the ice east of Cape Borgen, off Shannon Island. The cutter’s Captain Charles W. Thomas detailed the plan to capture the ship intact. “Under cover of darkness” the Eastwind would “crash a lead through the ice to a distance of 4,000 yards from the beset vessel, wheel sharply to right to unmask the after battery (a twin 5-inch mount), and fire three salvos—one short, one over, and one across the bow.” The cutter would “close to hailing distance, the Germans would be warned against scuttling ship or other sabotage, and [a] landing force would cross the ice and take possession of the enemy vessel.”

The plan worked. The cutter began firing 23 illuminating star shells at 2141, followed by 13 rounds of ready service ammunition. At 2250, the target ship blinkered, “We give up,” and the cutter ceased fire. The only casualties were two blades of the Eastwind’s starboard propeller “lopped off” as she swung around to begin firing. By 0220 the next morning, 17 enlisted German crew members were taken aboard the Eastwind, and 20 minutes later, the salvage party was on board the captured ship. The three German officers had remained behind with the boarding party to aid the salvage party with disarming destruction charges and preparing the ship for sailing. By 0600, they were aboard the cutter. The ship was identified as the “German Naval WBS Externsteine, expeditionary vessel of the Weather Station seized on the 4th.” She was quickly—and unofficially—renamed the Eastbreeze in honor of her captor.

It took almost the full day to free the ship from the clutches of “the heaviest [ice] the vessel has ever been in.” It was estimated to be ten feet thick. The cutter provided a prize crew of 25 men and three officers, while the accompanying Southwind (WAG-280) sent nine Navy personnel as passengers. Two days later, the Eastwind continued to break heavy pack ice followed by the Southwind with the Eastbreeze at times under tow; they finally reached open water at 0900 on 19 October.

By the end of November, the Eastwind was assigned to escort the Eastbreeze to Boston. The former German vessel had proven useful in service to the Greenland cutters up to that point. At 0627 on 5 December, the two arrived at South Boston Navy Yard.

Nine days later, the Coast Guard was not as circumspect as the Navy releasing the capture information. It was hard to disguise a ship with a bright red swastika-emblazoned Reichskriegesflagge surmounted by Old Glory entering Boston Harbor. A bold front page story—“Captured Nazi Ship In Boston”—and photograph of the ship in the harbor highlighted The Boston Globe on 14 December. Lieutenant Curtiss Howard, the Eastwind’s navigator and the skipper of the Eastbreeze prize crew, was quoted extensively about the background and history of the operation as well as its details: “[W]e’d been operating for a month off northeast Greenland . . . in the vicinity of latitude 75, about 800 miles from the North Pole and above the Arctic Circle.”

He noted the difficulty in spotting the German ship:

She was camouflaged as she is now—painted gray with the green and white blotches on her—and although it may not look like much here, it was very effective among the icebergs. Also, she had white bunting that looked like sheets spread over her deck to make her look like an iceberg, and if the light hadn’t been just right the pilot might never have spotted her.

With Greenland locked in ice for the remainder of the year and the Germans worried more about action closer to home in 1945, there was not much else for the Eastwind to do in terms of fighting the enemy. She remained homeported at Boston for the rest of her career, primarily continuing to support operations around Greenland. In January 1949, she was involved in a collision with the Gulf Oil tanker Gulfstream off Cape May, New Jersey, which severely damaged the cutter and cost the lives of 13 of her crew. Also in 1949, she was redesignated from WAG—Coast Guard, Auxiliary, General—to WAGB—Coast Guard, Auxiliary, General, Breaker. Among other deployments, including seven Deep Freeze operations during Antarctic summers from November to March in 1955, 1959–61, and 1963–65, she completed the first global circumnavigation by an icebreaker from October 1960 through May 1961.

The Eastwind was decommissioned on 13 December 1968 and sold for scrap in 1972.

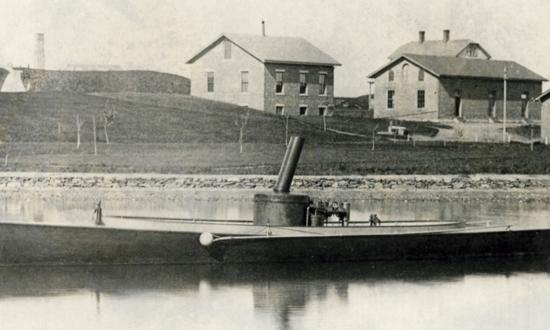

Unlike U-505, which eventually became the exhibit she is today at Chicago’s Museum of Science and Industry, the ex-Externsteine continued in U.S. service after the war. At the time of her capture, she was about a year old, built at P. Smit Jr. Shipyard, Rotterdam, Netherlands. Originally built as a trawler, she was used by the Germans as a weather ship and icebreaker and designated Weather Observation Ship (WBS) 11.

After her capture, she was temporarily commissioned as the USCGC Eastbreeze and served with the Coast Guard supporting operations off Greenland until being sent to Boston in December 1944. There she was transferred to the U.S. Navy and commissioned on 24 January 1945 as the Callao (IX-205). She moved to the Philadelphia Navy Yard and was outfitted for Bureau of Ships’ experimental work. Over the next five years, she conducted tests off Cape May and Cape Henlopen, Delaware. She was decommissioned on 10 May 1950 and sold for scrap on 30 September.