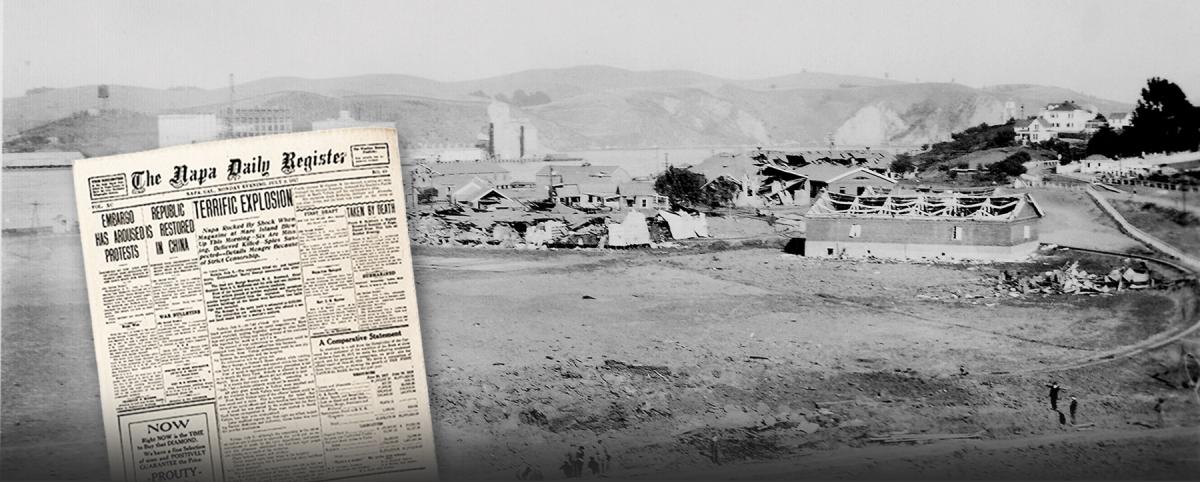

Early on 9 July 1917, the gunpowder magazine at the Naval Ammunition Depot on Mare Island, California, exploded, flattening several nearby buildings and killing six. Immediately, U.S. Navy officials blamed German sabotage, but the investigation proved inconclusive.

A century later, German responsibility, first assumed in 1918 and republicized in 1937, has become regarded as fact, with a dozen books and papers repeating the claim. A close examination of the historical record, however, reveals the claim to be false—and suggests an entirely different explanation.

German Agents Afoot in America

In early 1916, 34-year-old German-American private detective and former U.S. Marine Kurt Jahnke walked into the San Francisco office of the Justice Department’s Bureau of Investigation and declared that a German-American was planning an attack on Mare Island.1 Allegations of German espionage at Mare Island had broken in the press earlier that day, and news stories about German sabotage in New York had been circulating for several months.

The bureau likely thought Jahnke was an overeager patriot—but in reality, he was a double agent, sent to distract investigators with embellished press reports. Jahnke led the West Coast operations of the Etappendienst—a network of German naval intelligence agents who collected information and covertly resupplied German ships.2

Later that year, the Etappendienst received a new recruit, 21-year-old Midshipman Lothar Witzke. His ship, SMS Dresden, had been scuttled in Chile in March 1915.3 The wounded Witzke was interned, but he escaped and attempted to return to Germany. Upon reaching San Francisco, however, Witzke instead opted to join the ranks of Jahnke’s intelligence outfit and deployed to Mexico in 1917.4

The Mare Island Naval Ammunition Depot had begun with just a single building at the island’s southern tip. After a serious accident in 1892 involving untrained crewmen handling ordnance, the Navy began hiring specially trained civilian workers. Another accident in 1901 prompted the Navy to disperse the depot’s buildings farther north on the island, including the gunpowder magazine, built in 1907.5

The Navy was ill-prepared to combat German espionage and sabotage after U.S. entry into the Great War in 1917. Prewar espionage had forced the Navy to turn to the Justice Department and private detectives for investigators. With repeated sabotage alerts, Mare Island officials improvised, bolstering guards, installing searchlights, organizing informants, and firing four employees for alleged German sympathies.6

Obliterated by Gunpowder

Monday, 9 July 1917, began like any other day. Civilian ordnanceman Neil “Charlie” Damstedt began his rounds, sweeping the buildings and greeting colleagues. At around 0750, he arrived at the gunpowder magazine. He was standing on the steps when a wagon passed. Charlie said hello, opened the door, and walked the length of the building between stacks of gunpowder. Suddenly, at 0755, an enormous explosion obliterated the building.

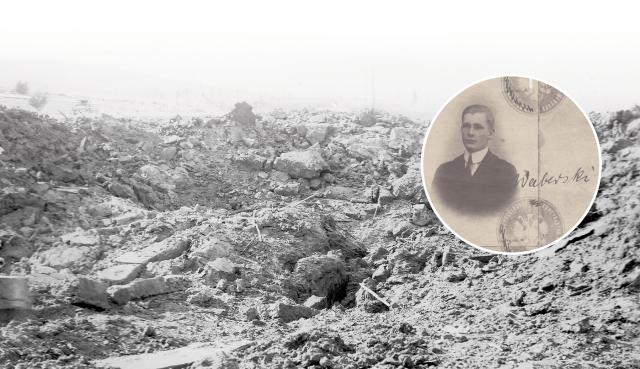

A detailed grid search recovered fragments of Damstedt’s lower body south of the building and fragments of his head east of the building. None of his remains were charred—suggesting he had been standing next to the source of the explosion.7

The explosion also obliterated the quarters of the depot’s two assistant gunners, James McKenna and Allan MacKenzie. MacKenzie, his wife, Malvina, and their two youngest daughters, Dorothy and Mildred, were killed. Their eldest, Roberta, was away and survived. George Stanton, a gardener working nearby, also was killed. Damstedt, Stanton, and the McKenzies were the only fatalities.8

Lothar Witzke, meanwhile, happened to be back in the area, acting as an Etappendienst courier between San Francisco and Los Angeles. After the explosion, he left San Francisco and never returned.9

‘Bring the Guilty Parties to Justice’

Mare Island officials requested Justice Department assistance but quickly leaked that the explosion was an act of sabotage. A Navy Board of Inquiry heard testimony from 179 witnesses, exonerating Damstedt but leaving the cause unexplained.10 In November, the Navy formally accepted the board’s findings, but Secretary of the Navy Josephus Daniels pressed to “continue to use all available means to discover the identity of the perpetrator of the explosion. The Department will continue such additional funds as may be required for detectives. Let no effort be spared to bring the guilty parties to justice.”11

The day the inquiry results were made public, double agent Kurt Jahnke, posing as a German naval officer, falsely claimed the Mare Island explosion was German sabotage. He approached a U.S. Army special agent in Los Angeles and relayed that two German naval officers from a ship interned in Mexico, a Russian ranch hand working near San Francisco, and one of the victims were responsible for the Mare Island explosion.12

Later, in early 1918, Lothar Witzke also allegedly claimed the Mare Island explosion was German sabotage. This time the audience was a group of fellow German agents. Dispatched with contact instructions for German agents in the United States, Witzke traveled, unbeknownst to him, with an American double agent named Paul Altendorf. According to Altendorf, it was during this trip that Witzke revealed his role in the Mare Island explosion.13

However, Altendorf told two versions of this story. In the first version, a 1918 Army intelligence debriefing, Witzke revealed he was a mechanic on Mare Island and wire-detonated 250,000 pounds of black powder in a magazine at about 0500, killing 16, including six children. Then, in 1919, Altendorf sold his story to the press saying another member of the German network had told him the story with no mention of Mare Island.14

A commission that investigated German sabotage from 1922 to 1941 included Henry Landau, a former British intelligence officer turned author. In 1937, Landau wrote a book publicizing Altendorf’s 1918 claim that Witzke had confessed to the explosion at Mare Island. After being digitized, the book is now referenced widely in serious history publications. However, Altendorf’s claims do not correlate with the Navy inquiry:

• The explosion occurred in a black powder magazine. (Public knowledge.)

• The explosion occurred at 0500. (Wrong—0755.)

• The magazine contained 250,000 pounds of black powder. (Wrong—127,660 pounds.)

• The explosion killed 16 people, including six children. (Wrong—it killed six people, including two children.)

• Witzke worked as a mechanic on Mare Island. (Unlikely—no workers were missing; all were thoroughly vetted.)

• The explosives were wire-detonated. (Unlikely—the detailed grid search found no wires.)

So, while Altendorf’s claims about Witzke sound vaguely plausible, they do not stand up to scrutiny. Witzke almost certainly had nothing to do with the Mare Island explosion. In fact, throughout his book, Landau inaccurately conflated the Etappendienst with the German sabotage network, attributing several West Coast explosions to Jahnke. Landau and Altendorf also claimed that Witzke confessed to the explosion of the Black Tom ammunition depot in New Jersey in 1916. However, the evidence again was weak, and the commission exonerated both Jahnke and Witzke of involvement in the Black Tom attack.15 They were, in fact, intelligence agents, not saboteurs.

Another Man, Another Motive?

The inquiry had noted that the civilian ordnanceman, Charlie Damstedt, “was in no way implicated” and blamed “persons unknown.” But with Witzke’s confession impeached, only Damstedt is left. He was in the building next to the source of the explosion when the blast occurred. Damstedt had the best opportunity to commit this crime—but what could have been his motive?

He was born Nils Karlsson Damstedt on a farm in southern Sweden in 1855. He left home to become a sailor and in 1880 joined the U.S. Navy.16 In 1887, the Navy invalided Damstedt out at Mare Island with a hernia. He briefly worked as a guard at the San Francisco Treasury but soon returned to Mare Island. A hero after an 1892 ammunition depot accident, he had been injured while hosing down flames surrounded by live shells and dying sailors. As the civilian workforce expanded, Damstedt became an ordnanceman. By 1917, he was the highest-ranking worker at the depot.17

Despite his hernia, at 61 Damstedt was still persevering—with an ill wife, a recently fired son, and two daughters still at home. Then, on Monday, 2 July 1917, he was unceremoniously demoted for cause and his pay halved. Inquiry testimony traced his emotions as shifting from denial to anger; one supervisor described Damstedt as brooding and resigned.18

One week later—the day of the explosion—appeared to begin like any other day for Damstedt. He was on the launch as normal. He commented on the unusually cold weather. Then he waved to the wagon driver on the steps of the gunpowder magazine at 0753 and walked into history.

The Navy inquiry denied any suggestion of attempted murder-suicide, and Damstedt’s long safety record ruled out an accident. However, there is no record that officials interviewed Damstedt’s family or friends, or checked his finances or life insurance. He did have life insurance, but no payment would have been made for death by suicide.19

Demoted, in chronic pain from his hernia, his son out of work, perhaps Damstedt felt he was worth more dead than alive. Modern suicide research supports the theory:

• The explosion happened on a Monday—more suicides occur on Mondays than any other day of the week.

• People who are demoted are nearly seven times more likely to commit suicide.

• While no suicide note was found, fewer than half of all suicides leave notes.

• Also, suicide by explosion is not rare, as numerous recent tragedies attest.20

The Navy inquiry had made little effort to investigate the possibility that Damstedt caused the explosion. In 1920, the Navy quietly characterized the Mare Island explosion as due to “causes unknown” and the MacKenzies’ deaths as accidental.21

Henry Landau’s 1937 book publicized Lothar Witzke’s “confession,” but it faded into obscurity. Only its eventual digitization led to the more widely held belief that the Germans had caused the explosion. That belief likely is misplaced; Landau never questioned Witzke’s alleged confession, and he had no idea that Damstedt had been demoted just one week before the explosion.

While we will never know for certain what caused the explosion at Mare Island, it seems unlikely to have been caused by German sabotage. That was a lie to confuse U.S. intelligence and bolster the image of German intelligence. Perhaps, in the end, it was just a cruel tragedy.

1. Henry Landau, The Enemy Within: The Inside Story of German Sabotage in America (New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1937), 34; U.S. Army, Military Intelligence, Mixed Claims Commission, memo (n.d.) marked Exhibit B, Witzke Courts-Martial Records, Record Group (RG) 76, Box 6, National Archives and Records Administration (NARA), Lanham, MD; and Richard B. Spence, “K. A. Jahnke and the German Sabotage Campaign in the United States and Mexico, 1914–1918,” The Historian 59, no. 1 (September 1996): 89–112.

2. Reinhard R. Doerries, Hitler’s Last Chief of Foreign Intelligence: Allied Interrogations of Walter Schellenberg (London: Frank Cass, 2003); Landau, The Enemy Within, 23–34; “Efforts Made to Dynamite Piers, Police Scent Plot to Blow Up the Non-Union Dock Workers in Seattle,” The Sacramento Union, 18 August 1916; Matthew Erin Plowman, “The British Intelligence Station in San Francisco During the First World War,” Journal of Intelligence History 12, no. 1 (2013): 1–20; and Robert Derencin, “Secret Naval Supply System of the German Imperial Navy in WWI.”

3. Landau, The Enemy Within, 34–35; “The Sinking of SMS Dresden, 14 March 1915.”

4. D. A. Sheehy, “A Résumé of the Log of H.M.S. ‘Orama,’ 1914–1917,” transcripts.sl.nsw.gov.au/page/404272/view, 39; “Merchantman Chased by German Cruiser—South American Adventures,” The (Melbourne, Australia) Argus, 12 March 1915; Landau, The Enemy Within, 10–11; 127; and Greg H. Williams, The United States Merchant Marine in World War I: Ships, Crews, Shipbuilders and Operators (Jefferson, NC: McFarland, 2017), 21.

5. National Park Service, “Historic American Buildings Survey: Mare Island Naval Shipyard,” loc.gov/pictures/collection/hh; Commandant, Mare Island,to Secretary of the Navy, 29 September 1917, “Report of Board to Investigate Explosion at Naval Ammunition Depot,” RG 125, Box 98, Case 7038, NARA, Washington, DC.

6. Jeffery Dorwart, The Office of Naval Intelligence: The Birth of America’s First Intelligence Agency, 1865–1918 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press 1979); “Code Book Trial Ends,” The Washington Post, 13 February 1916.

7. Mare Island Naval Shipyard Public Works Officer to Commandant, 14 July 1917, report showing condition of buildings at the Naval Ammunition Depot following 9 July 1917 explosion, RG 71, Box 40, NARA, Washington, DC; D. Benveniste, “The Early History of Psychoanalysis in San Francisco,” Psychoanalysis and History 8, no. 2 (July 2006): 195–233.

8. Commandant, Mare Island, “Report of Board”; “Nine Killed When Magazine Lets Go at Mare Island,” South Bend News-Times, 9 July 1917.

9. Robert L. Koenig, The Fourth Horseman: One Man’s Secret Mission to Wage the Great War in America (Cambridge, MA: Perseus Books, 2006); Landau, The Enemy Within, 102; and Lothar Witzke letter to LT Robert W. Hicks Jr., 23 March 1934, RG 76, PI 143/76 NARA, Lanham, MD.

10. “Mare Island Explosions Believed Due to Plot; Navy Officials Probing Disaster; Six Killed, 31 Injured,” Honolulu Star-Bulletin, 9 July 1917; Commandant, Mare Island, “Report of Board”; and “6 Dead, 38 Injured at Mare Island,” Sausalito News, 14 July 1917.

11. Commandant, Mare Island, “Report of Board.”

12. Intelligence Officer, U.S. Army Third District, Western Department, “Report—German Activities in the U.S. and Mexico,” 28 August 1917, RG 76, Box 5, “Documents relating to German sabotage activities, 1915–18,” NARA, Lanham, MD; Landau, The Enemy Within, 170–73; and Koenig, The Fourth Horseman.

13. Landau, The Enemy Within, 120, 171.

14. Paul B. Altendorf, “On Secret Service in Mexico,” Chicago Daily Tribune, 19 November 1919; Military Intelligence Branch Memo, 17 July 1918, addressed to CAPT. Edward McCauley, Office of Naval Intelligence; and U.S. Navy Bureau of Navigation, Officers and Enlisted Men of the United States Navy Who Lost Their Lives During the World War, from April 6, 1917 to November 11, 1918 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1920), 37.

15. Landau, The Enemy Within, 117, 223.

16. U.S. Navy enlistment records, NARA, archives.gov/research/military/veterans; Solano Archives, Solano County, CA, Naturalization Records, familysearch.org/search/catalog/1024615.

17. Langley’s San Francisco Directory, 1889, archive.org/details/langleyssanfranc1889sanf; Commandant, Mare Island, “Report of Board”; and Report of the Secretary of the Navy (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1892), 296, bls.gov/opub/uscs/1918-19.pdf.

18. Damstedt-Hathaway wedding announcement, San Francisco News Letter and California Advertiser, 2 January 1915; “Neil C. Damstedt;” and Commandant, Mare Island, “Report of Board.”

19. Commandant, Mare Island, “Report of Board”; Woodmen of the World Life Insurance Society Records, 17 April 1920, Universal Whole Life Certificate, “If the member holding this certificate shall . . . die . . . by his own hand . . . the certificate shall be null and void,” digital.library.txstate.edu/bitstream/handle/10877/9710/100_100_woodman.pdf.

20. Steven Stack and David Lester, “The Suicide of Ajax: A Note on Occupational Strain as a Neglected Factor in Suicidology,” in Suicide and the Creative Arts (New York: Nova Science Publishers, 2009), 49–53; Steven Stack and Ira Wasserman, “Economic Strain and Suicide Risk: A Qualitative Analysis,” Suicide and Life-Threatening Behavior 37, no. 1 (February 2007): 103–112; Toshiki Shioiri et al., “Incidence of Note-Leaving Remains Constant Despite Increasing Suicide Rates,” Psychiatry and Clinical Neurosciences 59, no. 2 (April 2005): 226–28; and Mallikarjun S. Ballur et al., “Strategic Evaluation of Suicide Notes,” International Journal of Current Research and Review 6, no. 17 (September 2014): 21–24.

21. U.S. Navy Bureau of Ordnance, Navy Ordnance Activities: World War, 1917–1918 (Washington, DC: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1920), 90; U.S. Navy Bureau of Navigation, Officers and Enlisted Men of the United States Navy Who Lost Their Lives During the World War, 37.