Daylight was fading into night as the German U-boat wallowed through moderate swells, her crew of 52 veteran submariners at full combat alert. Twenty days out of their home port of Lorient in German-occupied France, the crewmen of U-123 were ready for the attack.

Ten hours earlier, the U-boat’s lookouts had sighted the tiny wisp of smoke on the horizon. Kapitänleutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Reinhard Hardegen, 29, ordered a course to intercept and within an hour closed the distance to the target enough to identify it as a 10,000-ton British freighter.

U-123 was a Type IXB, the larger of the two mainstream U-boats in the war. Displacing 1,051 tons on the surface, the 252-foot-long, 21-foot-wide submersible had a maximum cruising range of 10,000 miles. Her weapons included a 105-mm deck gun and three smaller machine guns, but the main weapon was a loadout of 22 torpedoes. For the U-boat’s first target on this its seventh war patrol, Hardegen opted for a surface torpedo attack.1

The Cyclops was nearing the home stretch of a 13,485-mile trip from the Far East to the British Isles when disaster struck without warning at about 125 miles southeast of Cape Sable on Nova Scotia’s southern tip. The torpedo struck on the starboard side, blasting a fireball and column of seawater skyward. Master Leslie Webber Kersley, his 46-man crew, and 78 passengers took to lifeboats and rafts, but when they noticed the vessel was not sinking, a number reboarded.

On U-123, the radioman alerted Hardegen that the ship was sending out an “SSS” Morse code message reporting a U-boat attack. He ordered the U-boat closer, and from a point-blank range of 650 yards, struck her with a second torpedo. The Cyclops broke in two and sank within four minutes. The sinking doomed 86 of the 179 survivors of the attack, who would die of exposure before rescue ships arrived the next day.

The U-boat’s attack on the Cyclops on Sunday, 11 January 1942 was much, much more than another sinking achieved by a U-boat. It marked the opening of a deadly new phase in the Battle of the Atlantic: a six-month mass U-boat assault on merchant shipping along the East Coast and in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico.

Vice Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander-in-chief of the U-boat Force, gave the operation a simple but eloquent name: Operation Drumbeat.2

Wolf Packs’ Coveted ‘Green Light to Hunt’

By 1 January 1942, the U-boat Force had become a battle-hardened naval command under Admiral Dönitz’s stern leadership. Since the outbreak of the war, the force had grown from 57 to 248 U-boats. To date, the submarines had sunk 1,124 Allied ships totaling 5.27 million gross registered tons. To the 50-year-old Dönitz, that was not enough.3

Upon taking command of the nascent U-boat Force in 1935, Dönitz had calculated what it would take to strangle the British economy, and thus win the war at sea. His model was the 1917 U-boat campaign for a total blockade of the British Isles, when 60 U-boats in three months sank nearly 1,000 ships totaling about 2 million gross tons, including a record 423 ships in April 1917 alone. Dönitz calculated that a 300-boat force, with 100 at sea on any given day, could destroy two-thirds of Britain’s 3,000 merchant vessels within a year, cutting off the island nation’s vital imports of food and fuel. To achieve that goal, he lobbied vigorously for a force of 300 U-boats, split in a 2-to-1 ratio between the workhorse Type VII and the larger, long-range Type IX boats.

Dönitz’s plan went nowhere. His superiors at naval headquarters favored construction of battleships, cruisers, and destroyers over U-boats; worse, Adolf Hitler insisted Germany and Britain would never be enemies and resisted any naval expansion. Dönitz went to war against the British Empire with a paltry force of 57 U-boats, of which only 22 were fit for the North Atlantic.

“Seldom has any branch of the armed forces of a country gone to war so poorly equipped,” Dönitz later wrote in his memoirs.4

The first two years of the war were a time of major frustration for Dönitz and his U-boat commanders. Their paltry numbers made it impossible to mount large-scale wolf-pack attacks; their torpedoes were plagued with mechanical failures; the navy’s top admirals and Hitler himself continuously demanded U-boats be shifted for special operations—ranging from inserting Abwehr agents into Ireland to escorting the Norway invasion force—that had nothing to do with the war on shipping.5

What kept the U-boats in the fight was a simple fact that Dönitz had failed to appreciate. The British were just as unprepared to defend against the U-boats as the U-boats were unready for the war on shipping. The Royal Navy entered the war with a serious shortage of escort warships, which worsened with combat losses at Norway and Dunkirk. The Coastal Command, a Royal Air Force stepchild, struggled to patrol the sea lanes for U-boats with obsolete aircraft and ill-trained aircrews.6

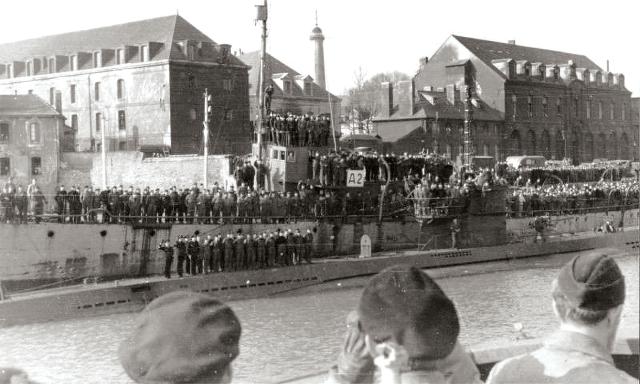

Not all news was bad. In June 1940, the Germans gained access to five seaports on the French Britannic coast. This gave the U-boats direct access to the North Atlantic. A year later, the belated submarine construction program began to show results, with the force growing to the point that by late 1941 at least 36 U-boats were on patrol at sea on any given day. During a four-month period nicknamed the “Happy Time,” the U-boats sank 282 ships totaling 1.48 million gross tons.

Then a new threat appeared: the U.S. Navy. In the fall of 1941, President Franklin D. Roosevelt ordered a major escalation of support for Great Britain. FDR secretly ordered Atlantic Fleet destroyers to join the transatlantic convoy escort operation, while dispatching Marines to Iceland to replace British troops who had occupied the island since 1940. Dönitz denounced the moves as a “chain of breaches of international law” and pressed for authority to confront the Atlantic Fleet. Still hoping to keep the United States out of the war, Hitler refused.

Despite the restrictions, the U-boats clashed with the U.S. destroyers in what became an undeclared war at sea. After the USS Greer (DD-145) and U-652 exchanged blows on 4 September, Roosevelt declared a “shoot on sight” order for the Atlantic Fleet. Six weeks later, U-568 fired at what her commander thought was a British destroyer but struck the USS Kearny (DD-432), killing 11 crewmen and damaging the warship. Then on 31 October, U-552 blew the USS Reuben James (DD-245) in half, killing 100 of the 144-man crew.7

Two days before declaring war on the United States on 11 December 1941, Hitler finally gave the U-boat Force the green light to hunt American warships and merchant vessels along the U.S. East Coast.8

‘Keep Washington Informed’

The war at sea was not fought with torpedoes and deck guns alone. As Admiral Dönitz prepared to deploy six of his long-range Type IX U-boats and a dozen Type VIICs to North America, he assigned another U-boat for a special mission.

When U-653 left on her first war patrol on 16 December 1941, her mission was not to hunt Allied shipping. Instead, Dönitz ordered Kapitänleutnant Gerhard Feiler to operate in the mid-Atlantic for several weeks as “a radio decoy.” Once on station, his radiomen transmitted dozens of encrypted messages to give the appearance of a wolf pack, hopefully masking the westward moves of the U-boats heading to America. Meanwhile, the Type IX boats—U-66, U-109, U-123, U-125, U-130, and U-502—quietly left on the month-long Atlantic crossing, followed by the Type VIIs.9

The false radio gambit was but one part of a second front in the Battle of the Atlantic that remained cloaked in the highest secrecy. U-653’s radiomen—together with scientists, mathematicians, and codebreakers ashore—waged an invisible war across the electromagnetic spectrum.

The U-boats and Dönitz’s headquarters relied on secure communications using high-frequency Morse code signals to report contact with enemy shipping and to organize attacks against Allied convoys. The Allies in turn depended on radio messages to receive rerouting instructions to avoid the U-boats. At the same time, both sides were mounting industrial-scale attempts to penetrate the enemy’s encrypted communications.

In what would later be recognized as one of the great ironies of World War II, both the Germans and Allies by early 1942 had succeeded in penetrating their enemy’s most carefully guarded naval communications without the other side knowing it.

Since 1940, the B-Dienst—the German naval cryptological service—had broken into several key British systems used by authorities ashore to communicate with convoy escort groups and manage convoy movements. Their success came in large part from capture of a number of coding manuals.

The British, in turn, had made an even greater penetration. After years of struggle, by late 1941 codebreakers at their field headquarters at Bletchley Park had thoroughly penetrated the German naval Enigma system.

Thought by Dönitz and other German military leaders to be unbreakable, the M3 naval Enigma machine found on all U-boats resembled an office typewriter but in fact was a complex encryption device that employed a series of three rotors, a stationary reflector, and other components to translate a clear-text message into a seeming gibberish of random letters. When the operator depressed a key, it closed an electrical circuit and a small light bulb behind one of 26 small glass windows illuminated. The letter that appeared in the lit window represented the encryption of the letter that the radio operator had just typed.

The genius of the Enigma machine was that in addition to the external inputs, the three rotors interacted with each other when the machine was in use. As the operator typed each succeeding letter in the message, the right-hand rotor would advance one step, creating a new encryption pathway. The other two movable rotors also advanced after a larger number of keystrokes. The result was that each letter in an Enigma message was encrypted by a separate and unique pathway.10

The British broke into German naval Enigma through a comprehensive, sustained effort. It included mathematical research, the capture of an intact M3 machine as well as a number of Enigma rotors and other coding manuals, and the cryptographers’ age-old mental work of testing encrypted passages against known decryptions.

The British also had established a series of high-frequency direction-finding (HF/DF) stations around the Atlantic that could grab a line of bearing to each U-boat radio transmission. The cross-bearings would provide a triangulation of the boat’s location with an accuracy of 25 miles.

Both the decrypted Enigma material and HF/DF reports were transmitted over secure lines to a top-secret facility in London known as the Operational Intelligence Centre (OIC). One of its key functions was managing the Submarine Tracking Room. From there, the OIC staff dispatched reports on U-boat operations to various Royal Navy units, and—since April 1941—to U.S. Navy headquarters in Washington.

By the morning of 3 January 1942, OIC Director Rodger Winn and his deputy, Patrick Beesly, were aware that Admiral Dönitz had deployed a force of 18 U-boats west across the Atlantic. They saw through U-653’s attempt to spoof them with her fake wolf-pack messages. Winn suspected that Dönitz was either preparing a U-boat patrol line in the western Atlantic or advancing to attack along the American coast.

Winn told his deputy, “Be sure that the people upstairs keep Washington informed.”11

What the U.S. Navy Knew—and When It Knew It

The classified alert message from U.S. Navy headquarters flashed out to all Atlantic Fleet commands shortly before 1300 hours on Tuesday, 13 January 1942:

12 JAN SUB ESTIMATE X INFO RECEIVED INDICATES LARGE CONCENTRATION PROCEEDING TO OR ALREADY ARRIVED ON STATION OFF CANADIAN AND NORTHEASTERN US COASTS X 3 OR 4 [U-]BOATS NEAR 40N 065W X 5 OR 6 SOUTH CAPE RACE PROBABLY NORTH OF 43N X 8 MORE WEST OF 30W PROCEEDING WEST

The message went on to give specific latitude-longitude plots for eight U-boats following behind the lead Drumbeat boats. It also confirmed the sinking of the Cyclops 41 hours earlier.

U.S. Navy commanders were well aware of the possibility U-boats might attack in American coastal waters. Late in World War I, six U-boats sank 90 ships totaling 166,907 gross tons in a brief but vicious offensive. Shortly before leaving the Atlantic Fleet to become Commander-in-Chief, U.S. Fleet, on 30 December 1941, Admiral Ernest J. King had sought the reassignment of destroyers to East Coast bases citing “the imminent probability of submarine attack.”

The alert message over the U-boat situation came from a more explicit source: For months, the OIC in London had been sending the U.S. Navy the top secret “U/B Situation” reports listing the known locations and activities of the German U-boat Force.

The OIC report on 12 January 1942 was blunt:

[T]he most striking feature is a heavy concentration [of U-boats] off the North American seaboard from New York to Cape Race [Newfoundland]. Two groups have so far been formed. One, of 6 U-boats, is already in position off Cape Race and St. John’s [Newfoundland], and a second, of 5 U-boats, is apparently approaching the American coast between New York and Portland [Maine]. It is known that a total of 21 boats [are heading] west.12

Five weeks earlier, the Japanese Kido Butai had achieved total strategic surprise at Pearl Harbor. This time, the U.S. Navy knew the U-boats were just hours away from attacking—including their numbers and precise locations.

Historian Michael Gannon, who discovered the explosive COMINCH alert message in the late 1980s, was savage in his assessment: “Perhaps no more telling attack warning, in unmistakable language and numbers, had ever come to the military forces of the United States.” And yet, the U.S. Navy still did nothing—even though 18 armed and combat-ready destroyers were available to respond to the threat.13

Skewed Priorities, Disastrous Consequences

As the Operation Drumbeat U-boats approached their attack areas on the evening of 13 January, senior U.S. and British leaders were ending the third week of a top-secret conference to set wartime priorities for the Western Allies. The Arcadia Conference had begun on 23 December when Prime Minister Winston Churchill and his senior military and political aides arrived in Washington after a transatlantic crossing on board the battleship HMS Duke of York.

Conference topics to date had spanned the globe: reaffirming the “Germany first” policy to focus on the war in Europe; selecting an Allied general to command coalition forces in the southwest Pacific; supporting the Soviet Union with military supplies; and organizing long-range plans for the invasions of North Africa and Western Europe.

One item that quickly rose to the top of the list and remained there when most of the others proved unworkable was the deployment of U.S. soldiers to Iceland and Northern Ireland as a public gesture of the United States joining the Allied war effort.

Speed was of the essence: Admiral King ordered that a troopship convoy would leave New York just three days later on Thursday, 15 January.14

To protect troopship Convoy AT-10, the Navy ordered a massive formation of Atlantic Fleet warships to its staging base in New York. Task Force 15 included the aircraft carrier USS Wasp (CV-7), battleship Texas (BB-35), three heavy cruisers, and 18 destroyers. At the last minute, four destroyers were reassigned to a second troop convoy heading to the Pacific.

Nevertheless, when Convoy AT-10 departed that Thursday morning, it would enjoy the protection of a veritable “curtain of steel” against U-boat attack. But the two convoys stripped the U.S. East Coast of the last destroyers available that could have confronted the U-boats. The decision by British and U.S. military commanders to prioritize sailing the troop convoys over defending the American coast set the stage for disaster.15

Blitzkrieg on the Atlantic Coast

As ordered by Admiral Dönitz, the five Drumbeat U-boats reached their assigned patrol areas by Tuesday, 13 January (a sixth, U-502, had been forced to abort her patrol after suffering a major oil leak). U-123’s target area spanned the coastline between Atlantic City, New Jersey, and Long Island, New York. U-125 was on patrol 100 miles offshore from Cape Cod to the Virginia Capes. U-66 was assigned the Outer Banks of North Carolina. Meanwhile, U-109 and U-130 had hunting areas off the northeast Canadian coast in the same general area of the 12 Group Ziethen U-boats.16

Hardegen quickly added to U-123’s count, sinking the 9,577-ton Panamanian tanker Norness and the 6,768-ton British tanker Coimbra on 14 January. Nor was that all.

Four other U-boats attacked and sank five allied merchant ships totaling 19,860 gross tons in the four-day period between U-123’s attack on the Cyclops and the scheduled sailing of the troopship convoys. Since not a single Allied merchant ship had been attacked west of Iceland in December, the sudden flare-up of sinkings from Newfoundland to Long Island galvanized the Atlantic Coastal Sea Frontier staff.

“The appearance of the enemy in such force gave little opportunity for warding off the blows that were struck so rapidly against the shipping,” wrote Lieutenant Lawrance Thompson in the Sea Frontier’s daily war diary. There were no warships to deploy against the U-boats; Convoys AT-10 and BT-200 and their 18 destroyers had left port on schedule.17

Reactions elsewhere to the sudden blitzkrieg along the coast and the soaring shipping losses were equally strong, although for opposite reasons.

In London’s OIC, Patrick Beesly was beside himself with frustration and anger. “With the information [about U-boat movements] available in OIC, the gist of which was passed on to Washington, it seems inconceivable now that the Americans could have been so completely and totally unprepared,” Beesly wrote.

Three hundred miles away in Lorient, Dönitz could hardly believe his good fortune. “Conditions [along the American coast] were almost exactly those of normal peacetime. The coast was not blacked out, the towns were a blaze of bright lights. . . .” He and his officers were soon calling the early months of 1942 the “Second Happy Time.”18

The disastrous week of 12–18 January 1942 set the stage for an unrelenting U-boat assault on merchant shipping along the U.S. East Coast and in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico. The carnage would continue nonstop through mid-July.

The losses were horrific. Off Newfoundland and along the East Coast, U-boats sank 226 ships totaling 1.25 million gross registered tons. In the southern theater, sinkings were almost identical, with 233 ships lost for a total of 1.12 million GRT. A total of 6,815 merchant sailors, naval gunners, and passengers perished in both areas, with 4,605 of them lost in the frigid North Atlantic.19

The U.S. Navy and Army Air Forces faced a very steep learning curve drenched in sailors’ blood as they tried—ineffectually at first, then with painstakingly slow progress—to learn effective antisubmarine-warfare tactics, assemble ships and aircraft capable of sinking U-boats, and finally, organize an effective coastal convoy system by mid-May.

By the fall of 1942, the Battle of the Atlantic shifted back to the northern convoy runs between North America and the British Isles. Buoyed by a surge in new construction, by September Dönitz was able for the first time to deploy an average of 100 U-boats at sea each day. The Germans also scored a major win in the war of codebreakers: On 1 February 1942, the U-boat Force began using a new, four-rotor Enigma machine, which blinded the British codebreakers for the rest of the year. This set the stage for a crisis of soaring shipping losses in the winter of 1942–43, culminating with a come-from-behind Allied victory over the U-boats the following May that finally drove the U-boats from the North Atlantic.20

In the end, the U-boats savaged Allied merchant shipping worldwide. They sank 2,919 merchant vessels and warships totaling 14.59 million gross tons. U-boat losses were, in the end, even worse: Of 830 commissioned boats, 717 went down at sea. Of 40,000 German submariners who went to war, 27,490 of them did not return.

Forced to endure strict food rationing, the British people struggled throughout the war. But they did not starve.

The Lingering Admiral King Conundrum

One mystery remains unsolved eight decades after Operation Drumbeat exploded along America’s shore: Why did newly appointed U.S. Fleet Commander-in-Chief Admiral Ernest J. King fail to respond to the clearly identified threat of the incoming U-boats? It is a mystery that promises to linger, for King—in his unofficial autobiography, official reports on the U.S. Navy, and postwar histories—remained silent.

Wartime censorship greatly assisted King and the Navy from having to explain the failure to thwart the U-boat offensive. The very existence of the British codebreaking triumph over the German naval Enigma would remain hidden until the mid-1970s. Even then, the critical “U/B Situation” report forwarded to Washington and the 13 January 1942 alert message from COMINCH to all Atlantic Fleet units remained buried for another 16 years until 1990. The “what” of our early wartime disaster is now known; the “why” seems no closer in reach than it was in 1942.

In the end, Admiral King stayed true to his most famous wartime dictum. Asked if he planned to implement a public-relations strategy to tell the American people about the Navy’s wartime effort, King replied: “Don’t tell them anything. When it’s over, tell them who won.”21

1. “U-boat Types,” uboat.net.

2. U-123 “Daily War Diary,” 12 January 1942, uboatarchive.net; “Ships Hit by U-boats,” uboat.net..

3. Clay Blair, Hitler’s U-Boat War, vol. 1: The Hunters: 1939–1942 (New York: Random House, 1996), 771.

4. Karl Dönitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days (New York: Da Capo, 1997), 9–10, 40–47.

5. Blair, U-Boat War, 101–103

6. W.S. Chalmers, Max Horton and the Western Approaches (London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1954), 149–56; Blair, U-boat War, 187.

7. Patrick Abbazia, Mr. Roosevelt’s Navy: The Private War of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, 1939–1942 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1975), 197–98, chapts. 20–25 passim; Dönitz, Memoirs, 189.

8. U-boat Force “Daily War Diary,” 9 December 1941, uboatarchive.net.

9. U-boat Force “Daily War Diary,” 25 December 1941.

10. David Kahn, Seizing the Enigma (New York: Random House, 1991), 195–98, 285–90; Michael Gannon, Operation Drumbeat (New York: Harper & Row, 1990), 425–26.

11. Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, 157–60; Patrick Beesly, Very Special Intelligence: The Story of the Admiralty’s Operational Intelligence Centre, 1939–1945 (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1977), 57–61.

12. “Operational Intelligence Centre Special Intelligence Summary,” 12 January 1942, PRO ADM 223/15, Public Records Office, Kew, UK.

13. Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, 212.

14. “The Arcadia Conference: December 1941–January 1942,” 155, 160–61, jcs.mil.

15. Ed Offley, The Burning Shore: How Hitler’s U-boats Brought World War II to America (New York: Basic Books, 2014), 101; location of Atlantic Fleet destroyers on 12 January 1941 from analysis of individual ship’s deck logs from National Archives, Record Group 24, College Park, MD.

16. Gannon, Operation Drumbeat, 199.

17. Uboat.net; Blair, U-Boat War, 727–28; Eastern Sea Frontier “Daily War Diary” January 1942, II, 3, uboatarchive.net.

18. Beesly, Very Special Intelligence, 105–6; Dönitz, Memoirs, 202.

19. Shipping losses and fatalities compiled by the author.

20. Kahn, Seizing the Enigma, 214; Ed Offley, Turning the Tide: How a Small Band of Allied Sailors Defeated the U-boats and Won the Battle of the Atlantic (New York: Basic Books, 2011), chapts. 10–13 passim.

21. Robert Heinl, The Dictionary of Military and Naval Quotations (Annapolis MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014), 258.