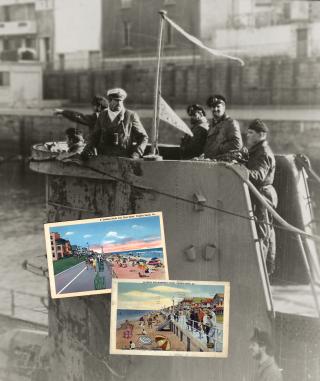

For the thousands of people splashing in the surf or lounging on the beach in the late afternoon on 15 June 1942, it would have been difficult to recognize that the country was at war. The only sounds were the shrieks of children’s laughter, the cry of an odd seagull overhead, and the gentle lapping of waves along the Virginia Beach oceanfront.

Frank Batten Jr. was as carefree as any 15-year-old that summer day. He and his family had driven from their home in Norfolk to the shore for a day of swimming and picnicking. Shortly after 1700 hours, the teenager waded back into the surf, his eyes locked on an intriguing sight in the near distance. During the past hour, a formation of 12 giant oil tankers had crept into view, shepherded by five small naval escorts.

As the ships reformed from two columns into single file to enter port, their cargo-laden hulls seemed to form a solid wall of steel blocking the horizon. “The ships were so close to the beach that we felt we could almost swim out to them,” Batten recalled many years later. As he idly watched, the fifth ship in line was suddenly rocked by a massive explosion that ignited her cargo of 152,000 barrels of crude oil, sending a black plume of smoke towering into the sky.

World War II had just erupted offshore within sight of 50,000 stunned beachgoers.

More Blasts and Confusion

Even before he had time to react, Batten and other swimmers felt a shock wave slam into their bodies. “The bottom of the ocean appeared to tremble,” witness G. F. Martin later told The Virginian-Pilot newspaper. The dull boom of the explosion followed 20 seconds later.1

In the chaotic minutes that followed, Robert C. Tuttle Master Martin Johansen—realizing that the explosion had torn a massive hole in the tanker’s starboard side—ordered his 47-man crew to abandon ship. After searching in vain for a missing crewman later found to have been blown overboard and killed, Johansen threw a weighted bag containing the vessel’s codes and confidential papers overboard and climbed down into a life raft.

Another ship captain nearby reacted swiftly to the blast. Fearing that the Robert C. Tuttle had been torpedoed by a German U-boat, the master of the 11,237-ton Esso Augusta immediately ordered his ship to full power and broke away from the formation. The two-year-old Standard Oil Company tanker, with her cargo of 119,000 barrels of diesel oil, began making a wide zigzagging turn to starboard just as a second explosion roiled the water several hundred yards away. Fifteen minutes later, as the tanker came full circle and resumed course to enter Thimble Shoal Channel, Master Eric Robert Blomquist thought he had evaded danger. He was wrong. A third blast rocked the Esso Augusta’s stern, ripping off her rudder and stern post.

Reaction to the attack came swiftly. Within 15 minutes, several U.S. Navy patrol aircraft appeared overhead and circled the battered convoy. As the stunned crowd on the beach and boardwalk watched anxiously, several of the planes swooped down and dropped depth charges on the suspected enemy. The captain of the Coast Guard cutter Dione (WPC-107) raced the convoy escort out several miles and dropped a spread of eight depth charges on a presumed sonar contact. The barrage triggered a ninth explosion.

Word of the assault spread like wildfire throughout southeastern Hampton Roads, and within an hour thousands more people were swarming to the beach to gaze at the spectacle. They did not have to wait long before the worst blow of all fell. At 1915 the British antisubmarine trawler HMS Kingston Ceylonite was escorting a damaged U.S. freighter into port when the patrol vessel vanished in a thundering explosion that killed her captain and 17 of her 32 crewmen.

Despite multiple eyewitness accounts claiming to have seen a U-boat, within hours, Fifth Naval District officials in Norfolk concluded that the explosions had come not from torpedoes but from a minefield laid across the mouth of Thimble Shoal Channel. The next day, a group of minesweepers steamed out to clear the channel but, due to a miscommunication, failed to sweep a broad swath to the east and northeast of Buoy 2CB. The mistake became apparent at 0750 on 17 June when the 7,117-ton collier Santore came down-channel from Baltimore to join a southbound convoy. United Press International correspondent Walter Logan and a photographer were on board one of the escorts and had a front-row seat for what happened next. “I was standing on deck lazily watching a grimy old collier,” he wrote, “when she blew up in my face.”2

The terrifying blasts that rocked northbound coastal Convoy KN109 as it prepared to enter Hampton Roads did more than mark the end of one of the most daring U-boat missions of World War II. It also signaled that a critical and deadly phase of the Battle of the Atlantic was drawing to a close.

A Shift in U-boat Tactics

To Admiral Karl Dönitz, commander-in-chief of the German U-boat Force, victory at sea relied on achieving one overarching goal: sinking enough enemy merchant ships to prevent an Allied military buildup in the United Kingdom for the liberation of Europe, and to strangle the British economy and drive Britain from the war. For the past five months, his U-boats had appeared to be making strong progress toward that end. Mounting parallel campaigns along the North American East Coast and in the Caribbean and Gulf of Mexico, U-boats since mid-January had sunk 459 ships totaling 2.37 million gross registered tons (GRT) and damaged another 56 totaling 366,989 GRT. More than 6,100 crewmen, naval gunners, and civilian passengers perished in the carnage. (See “The Drumbeat Mystery,” February, 12–19.)3

Studying the statistics of U-boat sinkings at his headquarters in Paris, Dönitz still believed that the submarine was most effective when attacking merchant ships with torpedoes. But the admiral was not averse to using U-boats for minelaying if the tactical situation called for it. At the outbreak of war in September 1939, U-boats, Luftwaffe aircraft, and surface warships had conducted several mass minelaying operations targeting most major seaports in the British Isles. That campaign had resulted in 30 ships sunk, totaling 104,000 GRT, and many others damaged.4

Dönitz’s decision to use front-line U-boats in a minelaying operation against East Coast ports in mid-1942 came in response to the belated organization of U.S. antisubmarine defenses and the creation of a coastal convoy system that went into effect in mid-May. Where U-boats for months had found rich pickings with unescorted tankers and freighters steaming independently along the coast, his skippers now were regularly reporting patrol areas devoid of targets.

In his Kriegstagebüch (Daily War Diary) on 19 May 1942, Dönitz explained that while normally it was “more worthwhile” to deploy U-boats with a full loadout of torpedoes—14 for the Type VIIs and 22 for the larger Type IX models—the shift in merchant traffic along the U.S. coast now increased the value of a mining campaign. “Even a few mines laid immediately off the busy entrances to New York (Delaware Bay, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Norfolk) are likely to lead to success as mine-countermeasures are sure to be few.”5

A ‘Very Special’ Mission

Kapitänleutnant (Lieutenant Commander) Horst Degen, commander of U-701, was a puzzled man on that early morning in mid-May 1942. He and his 46-man crew had finished their second war patrol six weeks earlier and were nearing the end of a protracted maintenance and refit period at their home port of Brest, France, when an urgent message arrived summoning him to U-boat Force headquarters via express train.

Thus far, the Type VIIC U-701 had compiled a respectable, if not exceptional, war record. Commissioned on 16 July 1941, the U-boat’s first war patrol had been with a German wolf pack assigned to patrol off Newfoundland at the onset of the Operation Drumbeat offensive along the U.S. East Coast beginning on 11 January 1942. The mission had been plagued by fierce winter storms that made sighting and attacking enemy ships all but impossible. Degen and his men had been able to sink only one vessel, a 3,657-ton British freighter.

The second patrol had been equally frustrating. Assigned to patrol a swath of the North Atlantic between Iceland and the Hebrides off Scotland’s west coast, U-701 spent a month dodging fierce gales, Allied patrol planes, and floating antiship mines. Degen and his men had to settle for sinking four small coastal patrol vessels totaling a mere 1,610 tons—about one-third the tonnage of a mid-sized freighter.6

Entering Admiral Dönitz’s Paris headquarters, Degen was informed that he and U-701 had been selected for one of the most dangerous of the mining missions: closing the entrance to Chesapeake Bay just miles from the largest U.S. naval base on either coast. Two other ports were targeted: U-87 was selected to mine the harbor channel outside New York (changed at the last minute to Boston), while U-373 would mine the entrance to Delaware Bay. The date for the minelaying, which would be aided by the blackness of a new moon, was just after midnight on Saturday, 13 June. Degen returned to Brest excited that his boat had been chosen for this “very special” operation.

Around this time, Degen learned that a separate U-boat operation on the U.S. coast was being prepared. Pressured by Adolf Hitler’s senior military staff, Dönitz ordered another pair of U-boats to infiltrate eight German saboteurs ashore on that same moonless night. U-202 would land four agents at the far eastern tip of Long Island, while U-584 would deploy the other four men at Ponte Vedra Beach, south of St. Augustine, Florida.7

Transatlantic Passage

Several weeks later, on 19 May, U-701 cast off from Brest on her third patrol. The first leg of the trip was an overnight passage down the Brittany coast to the larger U-boat base at Lorient. There, Degen’s crew loaded 15 TMB seabed influence mines, three apiece in U-701’s five torpedo tubes, with a reduced load of nine torpedoes on board. First developed in 1939, the TMB was a 7.5-foot-long aluminum cylinder, about one-third the length of the standard G7 torpedo, containing 1,276 pounds of hexanite high explosive—twice the power of the torpedo warhead. The mine had a timing clock to delay arming the weapon until the U-boat was well clear. Degen’s instructions were to set a 48-hour delay on deploying the mines.

For Type VII U-boats, having sufficient fuel was always a concern, given the vast distances to Western Hemisphere patrol areas. To handle the 3,177-nm trip from Lorient to Virginia’s Cape Henry, several weeks of subsequent patrolling along the East Coast, and the return voyage to France, Degen and his chief engineer engaged in a minor deception operation of their own. On arrival in Lorient, Degen reported to the 10th U-boat Flotilla staff that he had been unable to completely fill U-701’s diesel tanks before leaving Brest and needed several additional tons for the trip. “We wanted the expedition to last as long as possible,” Degen recalled years later. “The authorities at Lorient did not ask silly questions when we told them that fueling was not done completely in Brest.”

The three-week transit of the North Atlantic passed in relative calm. Cruising slowly on one engine to conserve fuel, Degen held U-701 on a direct course to the Virginia coastline. The crew fell into the normal at-sea routine of four-hour daytime watches and six-hour night watches at their workstations, interrupted only by crash-dive drills to keep them primed for evading the enemy. Degen’s two radiomen kept the crew entertained by playing popular music over the boat’s intercom.

Twenty-three days after leaving Lorient, U-701 crossed over the continental shelf, and Degen ordered the crew to battle stations. But as the hours passed without incident, Degen and his lookouts grew amazed. “There were no airplanes and no Coast Guard cutters as we drew nearer to the shore,” he recalled. It was now sunset on Friday, 12 June.

Unknown to Dönitz and the three minelaying U-boats, the Americans were generally aware that a mining operation was being planned. A U.S. Army intelligence agent in France had reported in April that such a campaign could commence as early as March. When April and May passed without incident, U.S. concerns eased. But on 10 June, the U.S. Navy received a tip passed on from a Chilean shipping executive to the U.S. embassy in Santiago that German officials there had warned the foreign minister to keep his country’s merchant fleet away from New York because of an imminent mining operation.

Vice Admiral Adolphus Andrews, commander of the Eastern Sea Frontier, issued an alert “letter” to all East Coast naval units warning of the threat. His message recommended that “every possible effort” should be made to sweep harbor entrances and channels. Andrews’ warning went out on 13 June and arrived at his East Coast subordinate commands on Monday, 15 June. Too late.8

Dropping the Mines

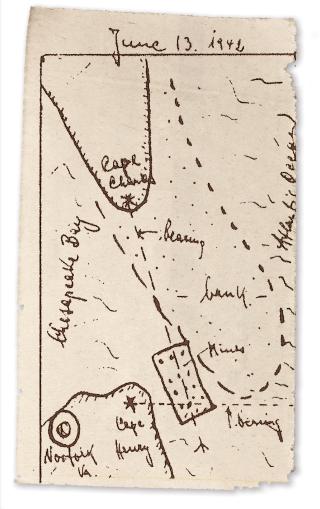

Several hours past sunset, as U-701 steamed inshore, Degen and three lookouts were manning the tiny bridge atop the boat’s conning tower when the bright lights of the Cape Henry and Cape Charles lighthouses sprang into view over the western horizon. The flashing lights clearly marked the 20-mile opening between the Virginia Beach shoreline and the southern tip of the Delmarva Peninsula.

Earlier in the crossing, Degen, navigator Günter Kunert, and his two watch officers had spent hours studying a large nautical chart of the area. They concluded that the strict operational order that Dönitz and his staff had written would doom U-701 to failure and probable detection. “Our order directed us to go straight to the entrance of Chesapeake Bay; to dive there during the night and to observe during the day the exact ship traffic of incoming and outgoing ships,” Degen recalled. But the chart showed that this meant U-701 would have to hide in just 36 feet of water, leaving her coning tower just four feet below the surface.

Dismissing the order as “suicidal,” Degen opted to make a straight run-in to the channel after midnight. The lighthouses on Cape Henry and Cape Charles would make the move simple and relatively easy. U-701 slowly headed west toward the Virginia Beach oceanfront.

After an hour, Kunert called out that the two lighthouses were aligned, and Degen ordered a 90-degree turn to starboard, running just several hundred yards offshore. Five months earlier, U-boats in the first coastal attacks had been amazed to find shoreline streets on New York’s Long Island brightly lit; now, after hundreds of ships had gone down from U-boat torpedoes, Degen and his lookouts were seeing the same “breathtaking” sight along the Virginia shore. “We could see . . . even cars and people and lighted houses,” Degen would recall. “These Americans didn’t seem to know there was a war going on!”

As the Cape Henry lighthouse loomed up ahead to port, Degen gave the order to his torpedo compartment to prepare to drop the mines. The torpedo gang flooded the five torpedo tubes and released the locking bolt that anchored the foremost mine in each tube. Before he could order the first mine dropped, Degen and his lookouts stiffened as a small patrol boat appeared traveling right to left across the U-boat’s track just several hundred yards away. She reached the edge of the channel, then reversed course, unaware that she was practically on top of the U-boat.

Glancing at his watch, Degen saw that it was 0130 local time. He gave a quiet order in the speaking tube, and a moment later, a jolt of compressed air ejected the first of 15 TMB mines, which sank to the channel bottom, about 50 feet down.

For the next 15 minutes, U-701 slowly zigzagged along the western side of the channel, dropping a mine every two minutes. When the pesky little patrol boat reappeared, Degen ordered the diesel engines shut down, and U-701 continued using her two electric motors. Slowly, the submarine turned around and repeated the maneuver on the eastern side of the channel, expelling eight more mines, As the last mine fell out of the stern torpedo tube, Degen again glanced at his watch: 0200. It had taken just 30 minutes to lay a deadly minefield across Thimble Shoal Channel.9

Once clear of the coast, Degen relit his diesels, and U-701 headed south at high speed to hunt Allied shipping off Cape Hatteras. The 15 mines lay on the shallow seabed, their timers counting down 48 hours to arming.

End of the Line for U-701

In the end, Admiral Dönitz’s minelaying and agent-landing operations were a partial success and a total failure, respectively. U-373’s minefield at Delaware Bay sank only a 396-ton steam tug, while U-87’s attempt to close the entrance to Boston yielded nothing. Two of the four ships that triggered Degen’s mines off the Virginia Capes—the Robert C. Tuttle and Esso Augusta—were raised, repaired, and returned to service. U-202 and U-584 successfully landed the two teams of saboteurs, but the two team leaders turned themselves in to the FBI and betrayed the other six men in exchange for their own lives. The six were convicted by a military tribunal and executed on 8 August.

During a two-week patrol off Cape Hatteras after the minelaying, Horst Degen and his crew added another 14,224 GRT to U-701’s record, sinking the 14,054-ton tanker William Rockefeller by torpedo and the patrol craft YP-389 by gunfire. They also damaged two other ships for another 14,241 GRT.10

But U-701’s luck ran out on 7 July when she was attacked by a U.S. Army Air Forces A-29 Hudson patrol bomber as she briefly surfaced to recharge her batteries. All but a handful of the 46-man crew escaped the U-boat, but before searchers could find them, they were swept out into the Atlantic on the Gulf Stream.

Forty-nine hours later, a Navy blimp sighted seven crewmen who were still clinging to life. One of them was Horst Degen.

1. Frank Batten Jr. letter to the author, 9 July 1982; G. F. Martin description from The Virginian-Pilot (Norfolk), 17 June 1942.

2. Actions of Masters Johansen and Blomquist and damage to tankers from affidavits on incident filed with the Eastern Sea Frontier, RG 38, National Archives and Records Administration, College Park, MD (hereafter NARA); Eastern Sea Frontier War Diary, June 1942, RG 38, NARA.

3. Karl Dönitz, Memoirs: Ten Years and Twenty Days (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1990), 45–47; shipping losses and fatalities compiled by the author.

4. Clay Blair, Hitler’s U-boat War, vol. 1, The Hunters, 1939–1942 (New York: Random House, 1996), 126.

5. Kriegstagebüch (Daily War Diary for Commander, U-boat Force), 19 May 1942.

6. Horst Degen, U-701: Glory and Tragedy, unpublished memoir provided to the author.

7. Minelaying operation of 12–13 June 1942 from Kriegstagebüch, 19 May 1942.

8. Eastern Sea Frontier War Diary, June 1942, chapter 2, RG 38, NARA.

9. Degen, U-701: Glory and Tragedy.

10. “Ships hit by U-701.”