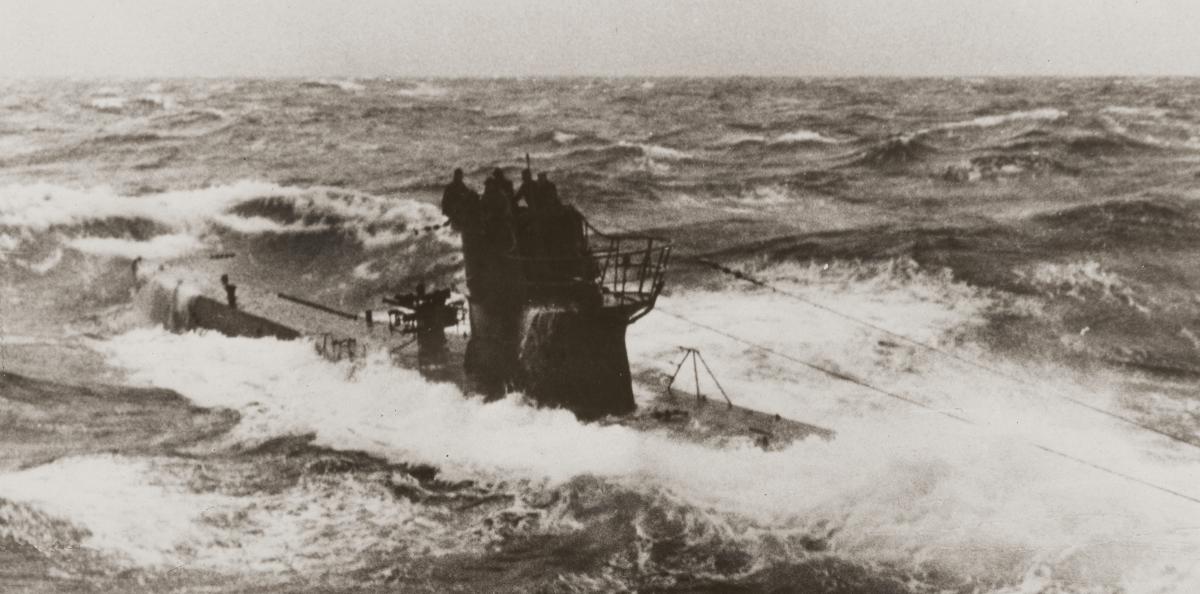

In a screwy world of trouble and uncertainty, of rancor and strife and normal life as we’ve known it upended by a drearily attenuated pandemic and other miseries, it is easy to succumb to a sense that this is just the worst—and to forget that wise old adage, “I cried because I had no shoes until I saw a man with no feet.” Yes, perhaps we live in what feel like stressful times, but think back to what folks were experiencing precisely 80 years ago this January: the launch of an all-out assault by Adolf Hitler’s U-boats on the American coast from Newfoundland to the Gulf of Mexico.

Hundreds of ships and thousands of lives were lost during Paukenschlag—Operation Drumbeat, which would sow terror and wreak havoc in American waters for the better part of a year. In our cover story this issue, author Ed Offley takes us back to those dark days of early 1942 and underscores one of the enduring questions of the whole affair: Where was the U.S. Navy? Why didn’t U.S. Fleet Commander-in-Chief Admiral Ernest J. King deploy the resources at his disposal to counter this ravagement right off the nation’s shores? It remains, to this day, one of history’s mysteries.

While the U-boats were a’prowl in the Atlantic in those opening months of the U.S. entry into World War II, over in the Pacific, a weight of responsibility so profound that it is tough to imagine was plunking down onto the shoulders of steely-eyed Chester W. Nimitz as he arrived at a Pearl Harbor still smoking from the devastation wrought by the 7 December 1941 Japanese attack. He had been serving as chief of the Bureau of Navigation when the call went out from President Franklin D. Roosevelt to Navy Secretary Frank Knox: “Tell Nimitz to get the hell out to Pearl and stay there until the war is won.” Through it all, how did Admiral Nimitz keep his cool? With a safety net of close family friends whose companionship and hospitality offered him the essential momentary respites from the madness to maintain his composure. Retired U.S. Navy Captain Michael A. Lilly offers us a rare glimpse at this private side of a great leader during wartime.

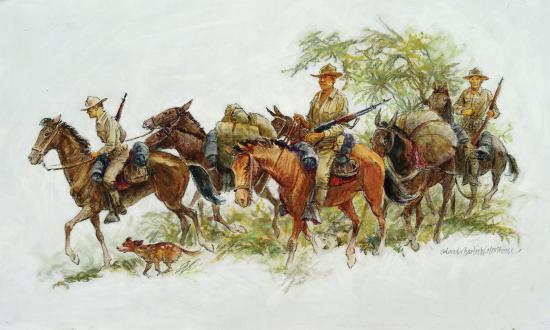

Nimitz was still getting settled in that January of 1942 when the Navy engaged in its first battle of the Pacific war: the raid on Balikpapan, Borneo, a major oil hub being overrun by the Japanese as they surged into the South Pacific. John J. Domagalski presents a fresh blow-by-blow account of this often-overlooked early U.S. naval engagement of the war—one that, while it failed to move the needle strategically, was nonetheless a tactical victory and a crucial morale booster to the fleet when it needed just that.

This February marks a noteworthy anniversary as well: the centennial of the signing of the Washington Naval Treaty, which defined the parameters of the great powers’ fleets in the years between World Wars I and II and, as John T. Kuehn observes, provided future generations with “a template for peace.”

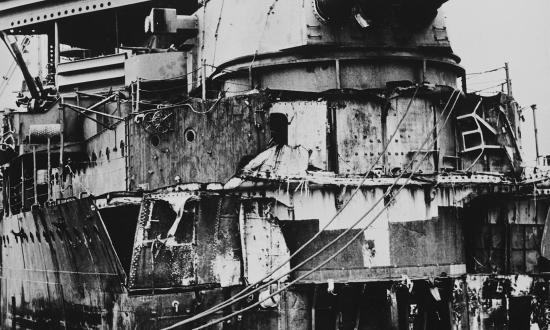

In those early 20th-century years, the U.S. fleet boasted a bizarre, distinctive innovation: the cage mast. As you will see in the images illustrating J. M. Caiella’s pioneering article on this fascinating topic, the towering, latticed cage mast was quite a unique sight to see—and in its rise and fall there is a potent lesson in how today’s technological advance may be tomorrow’s irrelevant concept.

Lastly, William J. Prom serves up an account of unsung heroes in the War of 1812, when a frenzied naval arms race unfolded in wilderness shipyards along the U.S.-Canadian borderlands. The victories of Perry at Lake Erie and Macdonough on Lake Champlain are celebrated in American naval lore—but behind these famed commanders was a genius pair of self-taught shipbuilding brothers, Noah and Adam Brown. Their output was phenomenal, fast, and executed under challenging conditions. Their story inspires us, and we hope it inspires you as well!

Eric Mills

Editor-in-Chief