The 1921–22 Washington Naval Conference is often portrayed as a strictly naval arms limitation conference, but in fact it was a broader event. The gathering in Washington, D.C., focused on naval force structures, but it also addressed an array of international community security concerns—many of them in the Far East—in the wake of the disastrous Great War. Scholars and, especially, naval historians have often regarded the conference as a failure, but in point of fact it was the inaugural gathering of what was hoped to be a series of conferences and a collective security regime that might prevent the recurrence of wars on the scale of World War I.1

Other historians, including the author, have been more generous in judging the conference and resulting treaties within the context of their times.2 In this sense, they were templates for the arms limitation and reduction talks and treaties of the Cold War era that prevented, to some degree, the recurrence of global total war. Given the present sad state of arms control, limitation, and reduction, the 100th anniversary of the signing of the Washington conference treaties is an ideal time to renew the current moribund system.

In 1921, U.S. Secretary of State Charles Evans Hughes, at the behest of President Warren G. Harding, invited the major powers to Washington, D.C., for a conference whose “objects . . . extended to three distinct topics, Limitation of Armament, Pacific and Far Eastern Questions, [and] Association of Nations.”3 Part of the purpose was to end an ongoing naval arms race between Japan, Great Britain, and the United States.4 Hughes dramatically initiated the Washington conference on 12 November with a speech in which he proposed the Harding administration’s plan for a reduction in naval armaments that included plans by the United States to scrap almost a million tons of battleships—both built and under construction.

The main elements in this proposal revolved around a capital ship building “holiday” of ten years and a fixed ratio for the tonnage of capital ships (battleships and battle cruisers) for the five major post–World War I naval powers: 5 (Great Britain) to 5 (United States) to 3 (Japan) to 1.75 (France) to 1.75 (Italy). The ten-year halt on capital-ship construction included prohibitions on replacing existing capital-ship tonnage. The other important features of Hughes’ proposal included scrapping more than 1.8 million tons of older ships and vessels under construction (with the United States scrapping the most) and a proportionate tonnage ratio to be applied to auxiliary ships.5

Despite applause and acclaim, Hughes’ masterful speech did not lead the other powers to immediately consent to his plan. Significant areas of dispute and many details remained to be resolved over the course of the next three months before a naval treaty would be signed.

Some members of the Japanese delegation—but not its chief delegate, Navy Minister Admiral Tomosaburo Kato—took issue with the “inferior” 3-to-5 (or 6-to-10) ratio that Japan’s fleet was assigned relative to the United States’. The Japanese delegation had been sent to Washington with instructions to accept no less than a 7-to-10 ratio in capital ships vis-à-vis the United States. The Japanese position was partly attributable to their potential U.S. adversaries. In the first place, there was the Imperial Japanese Navy’s reverence for the dictums of naval theorist Alfred T. Mahan. The Japanese and U.S. navies shared a common understanding of sea power because of Mahan. In the second place, the Japanese made their calculations based on intelligence for what the Americans projected as the size of their own fleet.6

Mahan had discussed maintaining the operational effectiveness of fleets over extended distances in his lectures on strategy. Using the example of Russian Baltic Fleet warships at the Battle of Tsushima Strait, he argued that the effectiveness of a fleet, despite numerical superiority, can be decremented by time and distance. Mahan claimed that these factors, without adequate basing or maintenance in naval yards, affect crew fatigue and the physical condition and seaworthiness of warships, especially those powered by steam engines.7

It was on this basis that American planners from the War Plans Division of the Chief of Naval Operations’ staff formulated a rule of thumb holding that “for every 1,000 miles a fleet steamed from its base, it lost 10 percent of its fighting efficiency.”8 Without bases beyond Hawaii, planners estimated the U.S. Navy would need a minimum of a 10-to-6 ratio in capital ships to maintain a slight superiority over the Japanese fleet, which would be located much closer to its own operating bases.

Japanese naval officers used the same process to deduce that they needed at least a 7-to-10 ratio to the U.S. fleet to maintain a margin of superiority. In addition, it appears that Japanese naval intelligence had acquired key elements of the naval portions of War Plan Orange, the U.S. plans for a possible war with Japan, which confirmed their calculations.9

The 10 percent chasm between the U.S. and Japanese positions, a difference that could completely derail the conference, was resolved within the Japanese delegation by Minister Kato. Overruling subordinates—particularly Vice Admiral Kanji Kato (not related), the bellicose technical representative from the Imperial Naval General Staff—the older and more influential Navy Minister built support among key senior leaders.10 These included Admiral Heihachiro Togo, the hero of Tsushima, as well as Prime Minister Takashi Hara.

Minister Kato offered the Americans a counterproposal: Japanese acceptance of the 60 percent capital ships ratio in return for the United States maintaining the status quo of fortifications in the Philippines and Guam.11 This offer was included in the conference’s 15 December 1921 announcement on agreement regarding capital ships:

It is agreed that with respect to fortifications and naval bases in the Pacific region, including Hongkong [sic], the status quo shall be maintained, that is, that there shall be no increase in these fortifications and naval bases except that this restriction shall not apply to the Hawaiian Islands, Australia, New Zealand, and the islands composing Japan proper, or, of course, to the coast of the United States and Canada, as to which respective powers retain their entire freedom.12

The compromise committed the United States to an inadequate system of naval bases to support its interests should war come to the Far East. Of course, the whole idea was that the conference’s naval treaty would further reduce that possibility by lessening the tensions between Japan and the United States. However, the U.S. Navy previously had designed its ships on the basis of extensive support ashore and had hoped to measurably increase its facilities in both Guam and the Philippines to support its assumptions in War Plan Orange. Either the Orange plan would have to be considerably modified, or entirely new warships would have to be designed and built and existing ships modified. In the end, the Navy would do both but not all at once, and it only grudgingly would modify its preference for an Orange strategy that immediately deployed the bulk of the fleet to secure the Philippines.13

By proposing the status quo clause, Minister Kato would manage to make the conference’s naval treaty politically acceptable at home, if not to certain elements of the Japanese Naval General Staff.14 The bases concession also was acceptable to the mostly civilian U.S. delegation. At the time, there was no approval or funding for western Pacific fortifications, and after the treaty went into effect, there would be no need to build any. In the view the Harding administration, Article XIX, the “status quo non-fortification clause,” would save the United States money.15

In balancing the ratio with the fortification clause, Minister Kato perhaps revealed a better understanding of the U.S. political system than the American delegates. He had “bet on the come,” gambling that the United States would neither build to limits for what it was allowed, for example, aircraft carriers, nor extensively in those categories of ships that were not limited, such as cruisers.16 Thus, while having potential parity with the Japanese in the western Pacific, the 5-to-3 ratio in fact worked out in favor of the Japanese if the Americans built anything less than they were allowed.

As it turned out, this would be exactly what happened. The cost-cutting Americans did not build to match the Japanese, despite the repeated protests of the General Board of the Navy in its annual building policy advice to the various secretaries of the Navy from 1922 to 1933.17 Navy leaders, on the other hand, were acutely aware of how this affected their strategic plans. While continuing to lobby both Congress and the various presidential administrations to “build to treaty limits,” Navy leaders also looked for innovative ways to ameliorate what they saw as the decreasing strength of their fleet relative to Japan.

On the Japanese side, Minister Kato also knew that what was prevented in peace was not prevented in the event of war. The conference confirmed Japan’s League of Nations Mandate for the Caroline and Marshall island groups between Hawaii and the Philippines, and they would be directly across the U.S. Navy’s line of advance in any plan to relieve the Philippines or move the fleet permanently to the western Pacific.

The Americans insisted that inclusion of the fortifications clause must be tied to Japanese accession to the Four-Power Treaty, an agreement between Japan, France, Great Britain, and the United States in which the countries agreed to guarantee peace in the Pacific by respecting each others’ territories in the region and not seeking further expansion. The pact effectively replaced the Anglo-Japanese Alliance of 1902. Kato agreed, with treaty being signed on 12 December, and the Japanese government would follow suit.18

On the other hand, Kato had to work very hard in crafting the final form of the status quo proposal in the face of opposition by Japanese Army, Navy, and government factions. They opposed the inclusion of some of Japan’s southern island groups (Formosa and the Pescadores). However, by the end of January 1922, Kato’s efforts were rewarded with his government’s assent to sign the resulting naval treaty.19

During the conference, another dispute arose over Secretary Hughes’ proposed extension of limitation ratios to auxiliary classes of ships, which had its origins in the capital-ship ratios. The French delegation, outraged by Hughes’ capital-ship proposals, demanded a larger ratio than Japan. However, Hughes went over the heads of the French naval officers by appealing to French Prime Minister Aristide Briand, who then directed his delegation to accept the proposal. In return, Briand informed Hughes that similar limitations on auxiliary ships would be impossible.20 This led to further disputes over topics including the size of cruisers, outlawing submarines, and ratios for aircraft carriers. The 1930 London Naval Treaty would resolve many of these issues.21

In the end, the only auxiliary limits adopted at the Washington conference were caps on the tonnage for individual aircraft carriers (27,000 tons), total tonnage for carriers that reflected the capital ship ratio (5-5-3-1.75-1.75), and tonnage for individual cruisers (10,000 tons), with these ships restricted to a maximum gun caliber of 8 inches. In another concession, the three major powers were allowed to convert two captial ship hulls under construction into aircraft carriers, resulting in the carriers Kaga and Akagi for Japan and the Lexington (CV-2) and Saratoga (CV-3) for the United States. But the British did not exercise this option because they would have had to scrap some of their existing carriers. Instead, they were allowed to complete the battle cruiser Hood. All the participants agreed that unrestricted submarine warfare was illegal, but Japan and the United States successfully argued for retention of submarines, stressing their value as fleet reconnaissance and screening assets.22

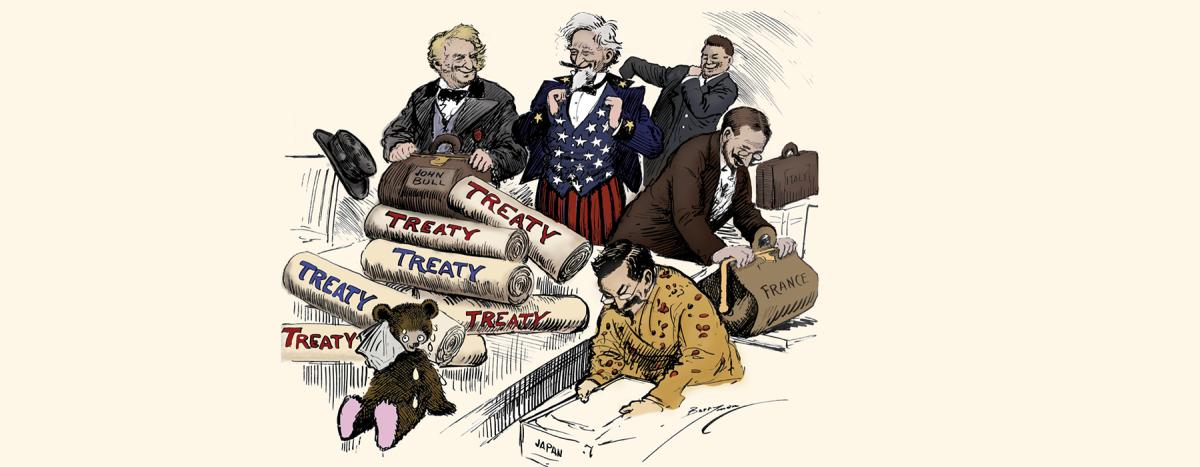

On 6 February 1922, representatives of the United States, Britain, Japan, France, and Italy signed the Washington Naval Treaty, also known as the Five-Power Treaty. Senator Henry Cabot Lodge, a conference delegate, outmaneuvered any U.S. opposition to it by pushing the treaty through the Senate without formal hearings—to include the testimony of Navy officers.23 Congress ratified the naval treaty on 29 March 1922.

To address China questons, a third major conference pact, the Nine-Power Treaty, also was signed by the five major powers plus Portugal, the Netherlands, Belgium, and China. It affirmed the “Open Door” for trade in China along with that country’s “territorial integrity.” However, a clause to this agreement, inserted by delegate Elihu Root (a former Secretary of War and of State) left in place the status quo for existing extraterritoriality in China by the signatory powers.24

Historians identify the failure to impose a comprehensive limit on auxiliary tonnages as the most significant shortcoming of the Washington Naval Treaty, since competition was moved from capital ships to other classes of vessels. The failure to cap cruiser construction worked in Japan’s favor; with no limits on auxiliaries, it was free to build as much as it could to further ameliorate the inferior position conferred by the ratio for capital ships. However, because of its government’s fiscal policies and—after 1929—the global economic depression, even Japan could not build without constraint. Some U.S. Navy officers thought the United States could keep ahead of the Japanese in auxiliary construction, but they would be proven wrong.

On the other hand, the fortification clause occupied center stage in the Navy’s collective response to congressional ratification of the naval treaty. Solving the problem of conducting a naval war in a theater devoid of forward bases would dominate the thoughts and actions of naval officers—including Marine Corps officers—for the next two decades.

In summary, the Washington Naval Treaty solved the immediate problem of a ruinous and expensive naval arms race and eased the recovery of European governments that were having problems paying for their World War I victory. It was greeted with acclaim by statesmen and the public around the globe, although not so much by the naval officer corps of the five signatory powers. But even for them the treaty had the perverse effect spurring innovative thinking. The U.S. Navy focused on new ship designs—particularly for aircraft carriers, submarines, and cruisers—and how to fight a long-range naval war with a limited number of battleships.

For almost 14 years, the United States, Britain, and Japan would not commission any new battleships—a fact often forgotten by those who criticize the treaty. An expensive naval arms race would not undermine world stability in the 1921–39 period, as might have been the case prior to World War I, and was perceived as such during the interwar years. A naval arms race did occur, but late in the period and only after Japan had chosen a course of aggression and expansion in China.25

As a template for future arms-control systems, the Washington conference has much to teach us about how to stabilize the present security environment, as well as the limitations of such agreements. The system inaugurated at Washington, above all, was allowed to decay, so that by the time of the Second London Naval Conference in 1935–36, it had become something that only the liberal Western powers adhered to.

In the last generation, the Cold War/post–Cold War system of arms-limitation agreements began tottering, some might even say collapsing, in the face of the geopolitical and geostrategic realities of a surging, revisionist China and resentful Russia. The George W. Bush administration began the process when it unilaterally withdrew from the Cold War–era Anti-Ballistic Missile (ABM) Treaty in 2002. Russia’s leadership responded that same year by effectively abrogating the Strategic Arms Reduction Treaty II (START II) governing, among other things, nuclear weapons. And the Trump administration withdrew from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in August 2019, opening the door for a renewed arms race in these types of weapons.26 It is time to reverse this destabilizing trend.

The United States could do no finer justice in commemorating the centennial of the original Washington conference and its treaties than by initiating a “redo” in 2022, inviting all the major and minor powers to Washington for an agenda that would curb the ongoing conventional and nuclear weapons arms races. The Washington Naval Conference, and its attendant treaties and agreements, provide a template for this approach, as well as a lesson in what can go wrong when the good intentions and work fall short of outcomes because of relaxed vigilance as well as impatience and national pride.

Dr. Kuehn is the author of Agents of Innovation (2008) and America’s First General Staff: A Short History of the Rise and Fall of the General Board of the Navy, 1900–1950 (2017), both published by the Naval Institute Press, and coauthor of The 100 Worst Military Disasters in History (ABC-CLIO, 2020).

1. See especially Samuel Eliot Morison, The Two-Ocean War: A Short History of the United States Navy in the Second World War (Boston, MA: Little, Brown & Co., 1963), 6; and Dudley W. Knox, The Eclipse of American Sea Power (New York: Army & Navy Journal, 1922), 133.

2. See John T. Kuehn, “The Influence of Naval Arms Limitation on U.S. Naval Innovation during the Interwar Period, 1921–1937,” doctoral dissertation, Kansas State University, 2007, 3, 12, 308–9.

3. Quincy Wright, “The Washington Conference,” Minnesota Law Review 6 (1922), 281.

4. George T. Davis, A Navy Second to None (New York: Harcourt Brace & Co., 1940), 275–76.

5. Senate Document No. 77, 11–17. These pages encompass the text of Secretary Hughes’ opening speech. See also Thomas Buckley, “The Washington Naval Limitation System: 1921–1939,” in Richard Dean Burns ed., Encyclopedia of Arms Control and Disarmament, vol. 2 (New York: Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1993), 642–43.

6. Sadao Asada, “Japanese Admirals and the Politics of Naval Limitation: Kato Tomosaburo vs Kato Kanji,” in Gerald Jordan, ed., Naval Warfare in the Twentieth Century, 1900–1945: Essays in Honor of Arthur Marder (New York, 1977), 141, 150–56.

7. A. T. Mahan, Naval Strategy (Newport, RI: Department of the Navy, GPO, 1991).

8. George W. Baer, One Hundred Years of Sea Power (Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1994), 95.

9. Sadao Asada, “From Washington to London: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the Politics of Naval Limitation, 1921–1930,” in Diplomacy & Statecraft 4, no. 3 (1993):149–50.

10. John T. Kuehn, America’s First General Staff (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2017), 221.

11. Asada, “From Washington to London,” 153.

12. Conference on the Limitation of Armament, Senate Document No. 126 (Washington, DC: GPO, 1922), 252.

13. Edward S. Miller, War Plan Orange (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1991), chapters 10–13 passim.

14. Asada, “From Washington to London,” 155–156.

15. GB 420-2 Serial No. 1083, 15 July 1921, RG 80, National Archives and Records Administration (hereafter NARA).

16. Asada, “From Washington to London,” 155.

17. See, passim, John T. Kuehn, “The U.S. Navy General Board and Naval Arms Limitation: 1922–1937 in The Journal of Military History 74, no. 4 (October 2010): 1129–60.

18. Sadao Asada, From Mahan to Pearl Harber: The Imperial Japanese Navy and the United States (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2007), 81.

19. Roger Dingman, Power in the Pacific: The Origins of Naval Arms Limitation (Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press, 1976), 210–12.

20. Buckley, “The Washington Naval Limitation System,” 643.

21. Kuehn, American’s First General Staff, 152–64; see also John Maurer and Christopher Bell, eds., At the Crossroads Between Peace and War: The London Naval Conference of 1930 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2014).

22. “Minutes of the Tenth meeting of the Advisory Committee,” 6 January 1922, GB 438-1, RG 80, NARA. These minutes were prepared for the American delegation at the Washington Naval Conference.

23. Buckley, “The Washington Naval Limitation System,” 645.

24. Wright, “The Washington Conference,” 280; Asada, Mahan to Pearl Harbor, 66.

25. S. C. M. Paine, The Japanese Empire: Grand Strategy from the Meiji Restoration to the Pacific War (Cambridge, MA: Cambridge University Press, 2017), chapter 5, passim.

26. See fas.org/nuke/control/abmt/chron.htm for ABM/START; for INF see Shannon Burgos, September 2019, at armscontrol.org/act/2019-09/news/us-completes-inf-treaty-withdrawal.