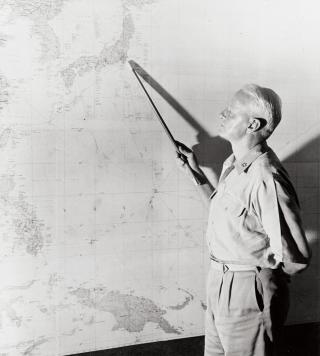

Admiral Chester W. Nimitz commanded the U.S. Navy’s Pacific Fleet and the Pacific Ocean Areas Theater during World War II, but his contributions to victory have been obscured by his modest leadership style. An “accommodating” and “nurturing” nature—well described by historians Craig L. Symonds and E. B. Potter—meant that Nimitz was content to see his subordinates receive accolades for battlefield successes while he remained in the background.1 But Nimitz’s style belied the extent of his skills. He used an aggressive theory of combat to overcome the inherent uncertainty of war and shape the conflict in the Pacific. Nimitz had an artistic ability to seize emerging opportunities, impose his command’s will on the enemy, and bring the war to a successful, and surprisingly rapid, conclusion.

Nimitz’s Theory of Combat

Nimitz developed his skills decades before the war. As a young officer, he was influenced by the Navy’s efforts to develop a coherent doctrine for naval combat. In the early 1920s, when Nimitz attended the Naval War College, that doctrine emphasized aggressive action to seize the initiative, control the pace of battle, and keep the enemy off balance.2

Nimitz’s thinking reflected these ideas. In his Naval War College thesis from 1923, he enumerated four “main and unchanging principles of warfare.” They were, first, “to employ all the forces . . . available with the utmost energy,” second, “to concentrate superior forces . . . where the decisive blow is to be struck,” third, “to avoid loss of time,” and, fourth, “to follow up every advantage gained with utmost energy.” To these, Nimitz added a series of “minor principles.” The most important were “attempt to surprise and deceive the enemy” and “great results cannot be accomplished without a corresponding degree of risk.”3

While Nimitz’s principles reflected the Navy’s emerging doctrine, the clarity with which he articulated his ideas was notable. His emphasis on timing, deception, and risk aligned well with the uncertainty of combat. He recognized that war was a “realm of probabilistic complexity” in which chance and the vagaries of human decision-making led to unpredictable and nonlinear outcomes.4 Alfred Thayer Mahan had brought this perspective to the Naval War College and integrated it in the curriculum. According to historian Jon T. Sumida, Mahan stressed the need for officers to develop an “artistic sensibility” that would allow them to continuously adjust their perspective to the dynamic circumstances of naval combat. Rigid plans were inadequate. Instead, officers had to approach combat like improvisational musicians and continually revise their plans based on the dynamics of energy, timing, and tempo to maximize the impact of their performance.5

Nimitz did just that during World War II. He used his tactical principles to integrate theory, experience, and action in a coherent whole that allowed him to deal with the “difficult, complex, and unpredictable” nature of war in the Pacific. He repeatedly displayed three approaches that translated his principles into action. He employed a disciplined approach to risk that allowed him to concentrate superior force at the decisive point; he used deception and surprise to keep the enemy off balance; and he deliberately created options to allow his forces to continually seek advantage as the war unfolded.6

Risking Concentration

For the first five months of the war, the most important force in the Pacific was the Imperial Japanese Navy’s (IJN’s) First Air Fleet, the Kidō Butai. An unprecedented concentration of naval air power, at full strength it contained six large, powerful fleet carriers. The Kidō Butai destroyed the U.S. Navy’s battle line at Pearl Harbor in December 1941, struck shipping and infrastructure at Darwin, Australia, in February 1942, and drove the Royal Navy from the Indian Ocean with strikes on Ceylon in April. Nimitz knew that so long as the Kidō Butai was unbloodied, the Japanese would hold the initiative in the Pacific.

When signals intelligence—especially the efforts of Station Hypo, the Navy’s combat intelligence unit at Pearl Harbor—began to give Nimitz insight into Japanese plans and operations, he moved to capitalize on the advantage. By 22 April, Nimitz knew the Japanese were planning to capture Port Moresby in southeastern New Guinea; he expected them to support the operation with five carriers.7 Although the IJN had the initiative and was “flushed with victory,” Nimitz planned an ambush. He and his staff hoped to “concentrate superior forces at the point of contact” and bring all four of their available carriers together for a major battle. Rear Admiral Frank J. Fletcher’s Task Force (TF) 17, with the carrier USS Yorktown (CV-5), was already in the South Pacific. The Lexington (CV-2) and TF 11 would join Fletcher soon. Nimitz planned to combine them with Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr.’s TF 16, containing the Enterprise (CV-6) and Hornet (CV-8). Nimitz expected that his “more resourceful and skillful personnel” and “fairly accurate knowledge” of the enemy’s plans would provide the margin of victory.8

After convincing the Navy’s new Commander-in-Chief and Chief of Naval Operations, Admiral Ernest J. King, to approve the operation, Nimitz issued his Operation Plan No. 23-42 on 29 April.9 It triggered the Battle of the Coral Sea. Unfortunately, Halsey’s carriers did not arrive in time. Fletcher won an important strategic victory by thwarting the Japanese invasion of Port Moresby, but the Lexington was lost and the Yorktown was damaged. In exchange, Fletcher sank the small carrier Shōhō and damaged the fleet carrier Shōkaku. “We can not,” Nimitz concluded, “afford to swap losses with this ratio.”10 Nimitz looked for ways to secure better results in the next carrier duel.

In early May, signals intelligence revealed that the Japanese were planning a series of offensives across the Pacific. The “K campaign” was the most important, but its target was unclear.11 On 13 May, Hypo intercepted a new message that linked the code group “AF” with the “K campaign.” Hypo had previously identified “AF” as Midway Atoll, and Nimitz’s intelligence officer, Lieutenant Commander Edwin T. Layton, quickly brought the new information to Nimitz’s attention. The following day, Nimitz’s intelligence summary concluded that the Japanese were planning “a campaign designed to take Midway . . . followed by an assault on Oahu.”12

This intelligence presented a remarkable opportunity. Halsey’s carriers were still in the South Pacific, positioned to strike a Japanese task force heading toward the Gilbert Islands. Nimitz quickly sent an “eyes only” message to Halsey asking him “to ensure that the enemy located TF 16.” Halsey acted as instructed and was sighted by Japanese patrol planes. They called off their attack on the Gilberts. Then Nimitz ordered Halsey to “proceed to [the] Hawaiian Area.”13 Fletcher was already on his way. With the Japanese convinced Nimitz’s carriers were in the south, he concentrated nearly all his available striking forces—his submarines, land-based planes, and carriers—at Midway to ambush the Kidō Butai.

This was calculated risk—a term often associated with the Battle of Midway—in the extreme. Unable to defend everywhere, and aware that a series of Japanese offensives were coming, Nimitz concentrated on the most vital area, the “Midway-Oahu line.”14 By doing so, he violated King’s standing orders to keep a carrier task force in the South Pacific. In their exchange of messages, it appears as if Nimitz engaged in a good-faith negotiation about the proper positioning of the Pacific Fleet’s carriers. However, he was retroactively justifying actions he already had taken. King did not officially approve of the concentration at Midway until 17 May, two days after Nimitz’s orders to Halsey. By then, it was clear that the enemy was intent on trapping and destroying “a substantial portion of the Pacific Fleet.”15

Nimitz was building his own trap. He packed Midway with planes, positioned submarines in an arc to the northwest of the atoll, and placed his carriers to the northeast, at “Point Luck.” Nimitz ordered Fletcher—commanding the carriers because Halsey was too ill— to “inflict maximum damage on the enemy” through “strong attrition tactics” and avoid “decisive action.” However, by 2 June, it was clear that the Japanese were coming. Nimitz instructed Fletcher to move west so that the carriers would be ready to strike immediately once the Kidō Butai was sighted.16

When that happened the morning of 4 June, Midway shot “the works,” Fletcher’s carriers attacked, and the trap was sprung.17 Before the end of the day, all four IJN carriers at Midway, the Akagi, Kaga, Sōryū, and Hiryū—the heart of the Kidō Butai—had been destroyed. The only U.S. carrier lost was Fletcher’s Yorktown. Midway’s “incredible victory” resulted from Nimitz’s effective application of his own tactical principles and his decision to embrace risk and concentrate superior force at the decisive point.18

Surprising and Deceiving the Enemy

Deception facilitated the victory at Midway. Nimitz’s carriers were not where Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto, Commander-in-Chief of the IJN’s Combined Fleet, expected them to be. By ensuring Halsey was sighted in the South Pacific, Nimitz gave Yamamoto the impression that he could secure Midway and then pounce on the Pacific Fleet when it came out to fight. By the time Yamamoto realized his error, the trap already had been sprung.

Nimitz continued to employ surprise and deception throughout the war. He was aided by the Joint Chiefs of Staff’s decision to “whipsaw” the enemy with two simultaneous “mutually supporting” offensives—one under General Douglas MacArthur in the Southwest Pacific and the other under Nimitz in the Central Pacific.19

Initial offensive steps were modest. Admiral King capitalized on the victory at Midway by initiating Operation Watchtower, the invasion of Guadalcanal and Tulagi in the southern Solomon Islands. Nimitz hoped to ensure the success of Watchtower with three deceptive operations intended to confuse the enemy about his true objective. The first was the light cruiser USS Boise’s (CL-47) raid on the Japanese “sampans and small cargo ships” patrolling “eight hundred miles east of Honshu.” The Boise was instructed to use her radio to “create the impression that a [carrier] striking force” was approaching Japan.20 The second was the assault on Makin Island on 16 August. The Second Marine Raider Battalion came ashore from the large submarines Nautilus (SS-168) and Argonaut (SS-166), seized control of Makin, and destroyed Japanese seaplanes and supplies before withdrawing. Finally, Nimitz ordered Rear Admiral Robert A. Theobald, his North Pacific commander, to bombard the Japanese-held island of Kiska in the Aleutians. Theobald’s ships attacked on 7 August, the same day the offensive in the Solomons began.21

None of these attacks diverted Japanese attention away from the assault on Guadalcanal. They struck Nimitz’s invasion forces with bombers from Rabaul and, on the night of 8 August, sank four Allied cruisers at the Battle of Savo Island. Operation Watchtower was supposed to have been the first step in a rapid advance northwestward through the Solomon Islands. It devolved into an attritional struggle, but it was one that Nimitz and his forces were able to win.

Nimitz wanted to keep his next major offensive—the drive through the Central Pacific that began with the assault on the Gilbert Islands in November 1943—from bogging down. In the runup to that operation, Nimitz’s forces raided Marcus Island, struck targets in the Gilberts, and attacked Wake Island. These strikes helped determine the best ways to organize multi-carrier task forces; they also drew out the IJN’s Combined Fleet. Admiral Mineichi Koga, its new commander, anticipated that the raids might be the start of Nimitz’s offensive and prepared to counter it. By the end of October, Nimitz was aware of these moves and recognized that the Combined Fleet was ready for action.22

But while Koga’s attention was focused on the Central Pacific, MacArthur was closing in on Rabaul. Operating under MacArthur’s “general directives,” Halsey invaded the island of Bougainville on 1 November. That convinced Koga that the greatest danger was in the south. He sent his carrier squadrons and most of his cruisers to Rabaul. Nimitz and Halsey soon became aware of Koga’s shifting dispositions.23 Halsey attacked the newly arrived Japanese cruisers on 5 November, foiling Koga’s plan to use them to disrupt the Bougainville landings. Nimitz sent another carrier task group south and delayed Operation Galvanic—the assault on the Gilbert Islands—a day to allow a follow-up strike on Rabaul.24

The ensuing air battle destroyed Koga’s carrier air groups. Half the Japanese fighters and more than 80 percent of their attack aircraft were destroyed.25 These losses, combined with the damage to the IJN cruisers, meant that Koga lacked the ability to oppose Operation Galvanic when it began on 20 November. Surprise and deception had enabled another crucial victory. Nimitz’s forces triumphed in the Gilberts and then, as planned, followed up their success by capturing the Marshall Islands. With Koga’s defenses collapsing, he withdrew his fleet from Truk to Palau.26

Creating Options

Another one of Nimitz’s wartime practices—the creation of options that allowed his forces to quickly exploit short-lived opportunities—helped him capitalize on Koga’s withdrawal. The Central Pacific offensive was governed by the Granite Campaign Plan. Granite contained a series of subsidiary operations, and each was an option that could be executed or discarded depending on circumstances. After Koga withdrew from Truk, the Japanese focused on their next line of defense, running through the Mariana Islands and Palau. Granite’s flexibility allowed Nimitz to forgo the intermediate operations of Gymkhana and Roadmaker—the assaults on Mortlock and Truk, respectively—and initiate Operation Forager, the capture of the Mariana Islands, five months ahead of schedule, in June 1944.27

Nimitz created options to take advantage of emerging opportunities throughout the war. During the Pacific Fleet’s first carrier raids, the strikes on Japanese positions in the Gilberts and Marshalls on 1 February 1942, Nimitz instructed Halsey to remain flexible and not focus on specific targets. Although initial plans called for Halsey’s TF 8 to strike relatively modest objectives on the Japanese perimeter while Fletcher’s TF 17 covered the attack, Nimitz left his options open so that he could capitalize on the latest developments.28

When signals intelligence and submarine reconnaissance revealed that the Japanese had no striking forces in the Marshalls, Nimitz ordered Halsey and Fletcher to undertake a more expansive operation. “Now is [the] opportunity,” Nimitz informed them, “to destroy enemy forces and installations [in] Gilberts [and] Marshalls, and it is essential that attacks be driven home.”29

Halsey divided his task force into three groups and simultaneously struck Wotje, Maloelap, and Kwajalein in the heart of the Marshalls. Rather than covering Halsey, Fletcher attacked targets of his own—Jaluit, Mili, and Makin. These aggressive attacks completely surprised the Japanese and disrupted their plans for upcoming offensive operations.30

Nimitz had employed the same pattern at Midway. “Point Luck” gave him options. Nimitz knew that the Japanese might bring five carriers to the battle and that the Yorktown might not be repaired in time. With his carriers positioned at “Point Luck,” too far away from the anticipated track of the Kidō Butai to get sucked into the battle, Nimitz could engage if the battle developed favorably or withdraw without risk of serious loss if it did not. As the Japanese approached, Nimitz became more confident. The Yorktown was in position and ready to fight. The Japanese would have four carriers, not five. On 2 June, Nimitz had Fletcher take the carriers west, “to insure” they would be “within early striking distance” of the enemy.31 Without that shift, the U.S. carriers would not have been in position to strike immediately, and the outcome at Midway would have been very different.

Nimitz continued to create options in late 1944, after capturing the Marianas. In September, when Halsey struck the Philippines in preparation for Operation Stalemate—the assault on the Palau Group—sparse Japanese resistance created an opportunity to accelerate the offensive once more. Nimitz abandoned plans to invade Yap and offered his assault forces to General MacArthur for an early invasion of Leyte. The Joint Chiefs and MacArthur approved, cutting two more months off the offensive’s timeline. Consistently throughout the war, Nimitz secured advantages and sustained a rapid operational tempo by continuously creating options that allowed his forces to exploit opportunities. That was one of the most crucial reasons why the Pacific war, which had been expected to continue into 1947 or beyond, concluded in August 1945.32

‘Artistic Sensibility’

During World War II, Nimitz used his artistic sensibility to translate his tactical principles into a coherent theory of combat. He relentlessly pursued options, he used surprise and deception, and he aggressively sought to take the initiative by embracing risk and concentrating force at the decisive point. These approaches helped Nimitz impose his will on the dynamic war in the Pacific by repeatedly disrupting Japanese plans and creating the conditions for victory.

Nimitz foreshadowed his approach in his tactical thesis. To help summarize his argument, Nimitz quoted retired Rear Admiral Bradley Fiske, who said that “there is no sharp dividing line” between strategy and tactics and that the difference between them is “the strategist sees with the eye of the mind, while the tactician sees with the actual eye of the body.” During World War II, Nimitz balanced nurturing leadership with strategic artistry; he “saw” with both of these eyes, coupled tactical outcomes to strategic goals, and became a genius who “does not follow the rules… [but instead] invents them.”33

1. Craig L. Symonds, Nimitz at War: Command Leadership from Pearl Harbor to Tokyo Bay (New York: Oxford University Press, 2022), xii; E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1976), 2; and Thomas Alexander Hughes, Admiral Bill Halsey: A Naval Life (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2016), 161.

2. Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 138–40.

3. “Thesis on Tactics,” CDR Chester W. Nimitz, 28 April 1923, Naval War College, Newport, RI. Emphasis in original.

4. Nonlinear outcomes are disproportionate ones, such as when a seemingly minor event has major consequences; see B. A. Friedman, “War Is the Storm—Clausewitz, Chaos, and Complex War Studies,” Naval War College Review 75, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 37–65; Anders Engberg-Pedersen, Empire of Chance: The Napoleonic Wars and the Disorder of Things (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2015), 79.

5. Jon Tetsuro Sumida, Inventing Grand Strategy and Teaching Command: The Classic Works of Alfred Thayer Mahan Reconsidered (Washington, DC: Woodrow Wilson Center Press, 1997), xiii–xiv.

6. Engberg-Pedersen, Empire of Chance, 79; Sumida, Inventing Grand Strategy, xiii–xiv; and Trent Hone, Mastering the Art of Command: Admiral Chester W. Nimitz and Victory in the Pacific (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2022), 341–54.

7. The efforts of Station Hypo during the early months of the war have been thoroughly examined by Elliot Carlson in Joe Rochefort’s War: The Odyssey of the Codebreaker Who Outwitted Yamamoto at Midway (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2011); and “Estimate of the Situation,” 22 April 1942, Command Summary of Fleet Admiral Chester W. Nimitz, USN, Nimitz “Graybook” [hereafter: “Graybook”], 1:371–407.

8. “Estimate of the Situation,” 22 April 1942, “Graybook,” 1:371–407.

9. CINCPAC Operation Plan No. 23-42, 29 April 1942, World War II Plans, Orders, and Related Documents [hereafter: Plans], Record Group 38, Records of the Office of the Chief of Naval Operations. National Archives, Washington, DC.

10. CINCPAC 102347, 10 May 1942, “Graybook,” 1:463.

11. SRH-272, Enemy Activities File, April–May 1942, 6–8 May 1942, Papers of Rear Adm. Edwin T. Layton, USN [hereafter: Layton Papers], Manuscript Collection 69, Naval War College Archives, Newport, RI; SRH-278, War Diary, Combat Intelligence Unit (Pacific–1942), 11 May 1942, Layton Papers; and COM14 Mailgram, “CINCPAC only,” 11 May 1942, Commander-in-Chief, Pacific and U.S. Pacific Fleets, Microfilmed Incoming and Outgoing Dispatches and Chronological Message Traffic, 1940–45 [hereafter: Messages], Record Group 313, Records of Naval Operating Forces, Entry (A1) 125, National Archives, Washington, DC.

12. SRH-272, 14 May 1942; SRH-278, 14 May 1942; Carlson, Joe Rochefort’s War, 308; and RADM Edwin T. Layton, USN (Ret.) et al., “And I Was There”: Pearl Harbor and Midway–Breaking the Secrets (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1985), 412.

13. John B. Lundstrom, Black Shoe Carrier Admiral (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2006), 210–11; 14 May 1942, CINCPAC 160307, May 1942, “Graybook,” 1:469, 480.

14. CINCPAC 160325, May 1942, “Graybook,” 1:471.

15. Lundstrom, Black Shoe Carrier Admiral, 211–12; Hone, Mastering the Art of Command, 81–82; and COMINCH 172220, 172221, May 1942, “Graybook,” 1:489–90.

16. CINCPAC Operation Plan No. 29-42, 27 May 1942, Plans; Jonathan B. Parshall, “What WAS Nimitz Thinking?” Naval War College Review 75, no. 2 (Spring 2022): 92–122.

17. Midway 041804, 041806, June 1942, Messages.

18. Walter Lord, Incredible Victory (New York: Harper and Row, 1967); Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, 15 vols. (1962; reis., Boston: Little, Brown, 1984), 4:105–40.

19. COMINCH 131250, February 1943, “Graybook,” 3:1435; “Conduct of the War in the Pacific Theater in 1943,” Memorandum by Joint U.S. Chiefs of Staff, 22 January 1943, C.C.S. 168, Casablanca Conference, January 1943, Papers and Meeting Minutes (Office of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, 1943).

20. Operation Plan No. 37-42, CINCPAC, 25 July 1942, Plans.

21. CINCPAC 300235, July 1942, CTG 7.15 200830, August 1942, “Graybook,” 1:629, 766; Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 4:235-41; CINCPAC 312145, July 1942, “Graybook,” 1:630; Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 7:9-12.

22. CINCPAC Operation Plan No. 12-43, 16 August 1943, Plans; 2, 14 September 1943, 7, 21, 26 October 1943, “Graybook,” 4:1647, 1657, 1670, 1675, 1677.

23. “Memorandum from Joint Chiefs of Staff to MacArthur, Nimitz, Halsey,” 29 March 1943, “Graybook,” 3:1473–74; John Miller Jr., The War in the Pacific, vol. 5, Cartwheel: The Reduction of Rabaul (Washington, DC: U.S. Army Center for Military History, 1959), 14; and 2–3 November 1943, COMSOPAC 030100, CINCPAC 030915, November 1943, “Graybook,” 4:1679, 1680, 1822, 1824.

24. 5–8 November 1943, CINCPAC 052111, November 1943, “Graybook,” 4: 1681–82, 1824; Potter, Nimitz, 255.

25. CTG 50.3 120321, November, “Graybook,” 4:1755; Morison, History of United States Naval Operations, 4:336.

26. Hone, Mastering the Art of Command, 222–26.

27. “Preliminary Draft of Campaign–Granite,” CINCPOA, 27 December 1943, Plans.

28. “Additional Considerations re Samoa Reinforcement Operation,” 8 January 1942, “Graybook,” 1:143–153; Lundstrom, Black Shoe Carrier Admiral, 56–57; and CINCPAC Operation Plan No. 4-42, 9 January 1942, Plans.

29. CINCPAC 280311, 28 January 1942, “Graybook,” 1:193.

30. Lundstrom, Black Shoe Carrier Admiral, 59–63; Hone, Mastering the Art of Command, 37, 46–48.

31. Parshall, “What WAS Nimitz Thinking?”; CINCPAC Mailgram 292049, May 1942, Messages; Lundstrom, Black Shoe Carrier Admiral, 222, 234–35; and COM 14 310545, COM 14 310934, CINCPAC 311221, May 1942, “Layton Notebook,” vol. 2, Layton Papers.

32. CCS 313, “Appreciation and Plan for the Defeat of Japan,” 18 August 1943, Quadrant Conference, August 1943: Papers and Minutes of Meetings (Office of the Combined Chiefs of Staff, 1943), 153–70; CCS 323, “Air Plan for the Defeat of Japan, 20 August 1943, Quadrant Conference, 288–300; and LTCOL Henry G. Morgan Jr., Planning the Defeat of Japan: A Study of Total War Strategy (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, 1961), 116–19.

33. Bradley A. Fiske, The Art of Fighting (New York: Century Co., 1920), 62; Engberg-Pedersen, Empire of Chance, 78.