The day after Admiral Chester W. Nimitz took command of the Pacific Fleet, the press asked what he was going to do with his battleships underwater.

Responding, Nimitz said he was a Kama‘aina and replied with a Hawaiian word, ho’omanawanui.1 Where did he learn that word and what did he mean?

Nimitz freed himself physically and emotionally from the enormous stresses of command through his relationship with a prominent Honolulu couple, Una and Henry A. “Sandy” Walker.2

Using Una’s war diary; hundreds of letters exchanged with Nimitz, his aide, and his subordinate leaders; the admiral’s 4,023-page daily command log, the Graybook; family oral history and memoirs; and war photos and memorabilia never before published, I was able to chronicle for the first time Nimitz’s daily activities in war and peace.

What emerged was the story of how the Walkers gave Nimitz a place, space, and time free from the horrors of war and the demands of command, which, in a small but meaningful way, helped him remain an able and effective leader and win the war in the Pacific.

In 1920, as a 35-year-old lieutenant commander, Nimitz was ordered to build the Pearl Harbor submarine base. He and his wife, Catherine, lived off base in the peaceful valley of Manoa not far from the University of Hawaii. Their nearby neighbors were the Walkers, who became lifelong friends.

By 1941, Sandy was president of the largest company in Hawaii, American Factors (later, Amfac). Una was chair of the Hawaii Red Cross Surgical Dressing Corps. They lived about two miles up Nu‘uanu Valley from Honolulu in an historic Victorian manor house nestled among 13 acres of orchid gardens and tropical fruit trees. On relieving Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, Nimitz resumed his friendship with the Walkers.

Nimitz served as both Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, and Commander-in-Chief, Pacific Ocean Areas. He was the supreme commander, overseeing the immense effort fighting the Pacific War. His job brought extreme stresses because he ultimately was responsible for all successes and failures.

Nimitz wrestled daily with the ever-changing, three-dimensional chessboard of war, much of it concealed behind the fog of combat and misinformation.

The Battle of Midway, the first major turning point of the Pacific war, could have been Nimitz’s nadir. Initially, he and his lead cryptanalyst in Hawaii, Commander Joseph Rochefort, were almost alone in their conviction that Midway was Japan’s target. Even then, the U.S. Navy was outgunned four carriers to three. Not until the knuckle-biting end did Nimitz know he was facing honors and not disgrace.

He also agonized over issuing commands he knew would result in death or injury to thousands of service members. Their deaths brought awful letters from bereaved parents by the hundreds. “You killed my son on Tarawa,” a bitter mother painfully wrote. Nimitz’s personal aide, Lieutenant Commander H. Arthur “Hal” Lamar, tried to hide the letters, but Nimitz insisted on reading each one and writing a personal letter of condolence in response.

“I am just as distressed as can be over the casualties,” he admitted to his wife, “but don’t see how I could have reduced them.”3 In another letter, he prayed for the war’s end to “stop this killing and maiming.”4

Nimitz routinely visited hospitals throughout the Pacific to award Purple Hearts and give encouragement to the wounded, some seriously disfigured or missing limbs. He cheered one mortally wounded 19-year-old soldier at Aiea Naval Hospital, saying how proud he was of his bravery shortly before the soldier died with a smile on his face.

Reading the Graybook, one is struck by the range of issues and problems, great and small, with which Nimitz dealt daily: He led the fight against the Japanese in most of the western Pacific; dealt with the imperious General Douglas MacArthur, who controlled Southwestern Pacific forces, with a gentlemanly cool; and skillfully maneuvered the political minefield in Washington comprising the Joint Chiefs of Staff, Chief of Naval Operations Admiral Ernest King, and President Franklin D. Roosevelt. As one author put it, Nimitz “lay like a valley of humility between two mountains of conceit: Ernest King and General Douglas MacArthur.”5

He also was the ultimate disciplinary and administrative authority in the Pacific. He promoted, demoted, and rewarded. “They will hate me,” Nimitz lamented to Catherine after court-martialing officers for running a large gambling ring. He did not “object to gambling for small stakes for amusement or entertainment,” but the ring was “bad for the military. . . . So you see,” he concluded, “I have minor problems besides the Japs.”6

The military does not prepare leaders such as Nimitz for handling such tensions. For Nimitz, these pressures manifested in chronic insomnia and intestinal distress, sometimes exasperated by recurring malaria contracted during a visit to Guadalcanal. In an era before air conditioning, Nimitz tossed and turned in the often-muggy climate of Pearl Harbor. He routinely arose in the night to study charts of the Pacific papering a war room in his quarters. Only the occasional good news recorded in the Graybook offered some solace.

Nimitz was able to find time “at ease” to shed his wartime responsibilities and find space and time to rejuvenate. Most of that time was spent with the Walkers.

Nimitz’s main refuge became the Walkers’ six-acre Laie beach house on the north shore of Oahu called Muliwai, Hawaiian for river water flowing over a sand bar into the sea. Wherever a stream entered the sea, such as at Muliwai, its fresh water killed coral, creating a navigable channel for an invading Japanese force. In defense, the Army strung four million feet of barbed wire on the beaches, including Muliwai.

The Walkers were unaware of this effort until one Saturday not long after Nimitz took command. Sandy donned beach clothes for a swim when he was confronted by nine rows of unexpected barbed wire. Threading his way through the maze of wire, a soldier in green suddenly appeared with rifle. “Halt, this is off limits!”

“But,” replied Sandy, “this is my beach.”

“Sorry, but I have my orders.”

“Well,” muttered Sandy, “we’ll see about that.”

On Monday, Sandy called Nimitz. “Would you like to spend the weekend at Muliwai?” Nimitz had heard about the Walkers’ hideaway and accepted.

The next Saturday, Sandy asked Nimitz, “Would you like a swim in the ocean?” As a lifelong athlete, Nimitz accepted with pleasure.

The duo donned swimsuits and proceeded down the maze of wire. The soldier again appeared and was about to say the beach of off limits when he recognized the well-known white-haired Nimitz, who was his ultimate commanding officer.

Nimitz’s steely blue eyes informed the soldier that the beach was not off limits to the Walkers or their guests, and that they could swim there any time they wished. Henceforth, Muliwai became Nimitz’s retreat, with him spending nearly every weekend of the war there until he moved his command to Guam in late January 1945.

During the day, Nimitz and the Walkers swam, pitched horseshoes, played paddle tennis on a grass court, and hiked in the verdant hills across Kamehameha Highway. In the evening over cocktails, they watched the sun set behind the jagged Koolau Mountains, tingeing puffs of clouds with crimson hues—one of the most spectacular views in the world.

At night, they enjoyed Kauai charcoal-broiled steaks served on a long koa table under the eaves outside the living room. After dinner, they listened to symphonies broadcast by radio or played on a record player and danced and played cribbage or poker.

They watched the stars “come up over the ocean. We’d talk about orchids,” mused Lamar. “We’d talk about mundane things. The war never came into the picture.” Nimitz “enjoyed very much” his time at Muliwai. The Walkers “let him get in an aloha shirt and a pair of shorts and talk no business at all. It was very relaxing for him.”7

A Muliwai evening was never complete without Una bringing out her ukulele to sing haunting Hawaiian melodies or popular ditties such as “Coconut Willie” and “Princess Pupule has Plenty Papaya.” Her repertoire included wartime songs such as “They Can’t Take Ni‘ihau No-how!” which recounted sheepherder Ben Kanahele’s battle with a Japanese pilot who crash-landed on the island of Ni‘ihau after Pearl Harbor. Another favorite was “She’s a Knockout in the Blackout.”

Gracefully strumming her ukulele, Una’s melodic voice echoed in the dark with the trade winds blowing in from the sea. For Nimitz, the gulf between his warfighting and friendship with the Walkers was wider than the Pacific.

The admiral slept in a separate two-bedroom, one-bath cottage the Walkers erected on a bluff overlooking the ocean. Unlike Makalapa, where the toils of war and his room of Pacific war charts forever beckoned, he had no distractions at Muliwai. The humid air carried the sweet scent of tropical plants that were mildly intoxicating. Nimitz immediately fell asleep to the sounds of the ocean and occasional squalls beating a tattoo against the roof until awakened by the sun bursting from the horizon.

Over time, Nimitz spent so many weekends at Muliwai that it became an easy routine. The Walkers no longer entertained Nimitz as a guest; their near-constant companionship had become so close that he was not just a good friend, but rather a family member.

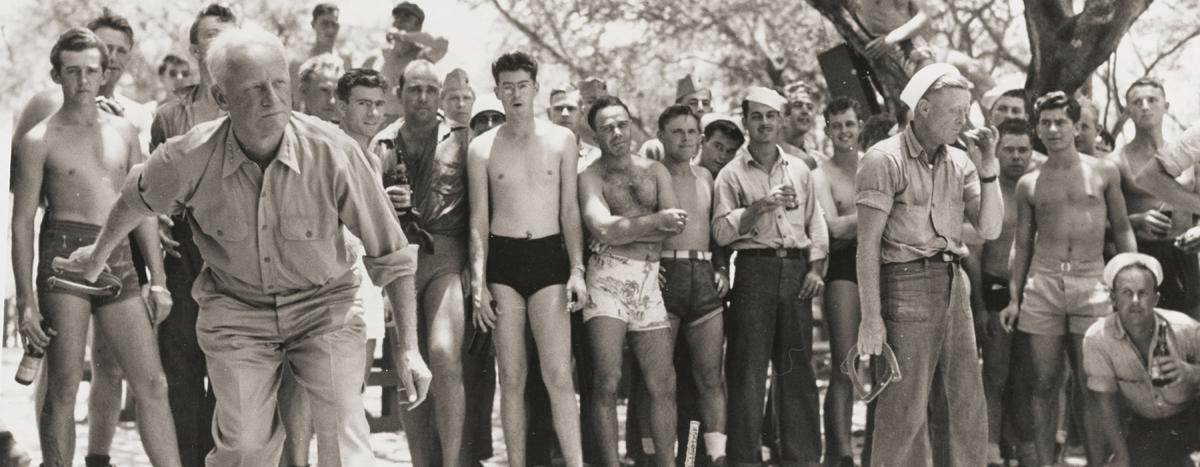

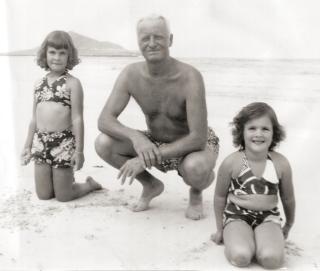

On Saturday, 3 April 1945, whimsical photographs were taken. him is always pictured in uniform or civilian attire. At Muliwai, he wore a swimsuit with the author’s young sisters, Maile and Sheila (who Nimitz nicknamed Major and Minor Gremlin), crawling all over him. His face reflected the calm peacefulness of a weekend at Muliwai. Behind him was another man in swim shorts. Admiral Thomas Hart was in Hawaii conducting an inquiry into the attack on Pearl Harbor. That morning, he was taking testimony but adjourned to join Nimitz for a weekend “at ease.”

Once a week, Nimitz showed up at the Walker mansion in Honolulu and drove them over a narrow pass—the Pali—to Kailua Beach. For security, the sojourn was never scheduled or noticed in advance. At Kailua, they walked and partly swam five miles from one end of the beach and back.

In Makalapa, Nimitz was forever besieged by VIPs, both civilian and military. Complaining to Catherine, he wrote that, while pleasant, they often interfered with his regular lunchtime sunbath. Dinners often stretched late into the night.

Having the sociable Walkers to round out his dinner table ensured lively conversation. For all their gregariousness in crowds, politicians can be the worst bores, or even shy one-on-one. Some military officers could barely hold a conversation outside military subjects. Being well-traveled, inquisitive, and exceedingly pleasant, Sandy and Una provided interesting conversations. They were patient listeners, flattering when needed and knowledgeable on most subjects. For Nimitz, who was daily besieged with guests from all walks of life and temperament, the Walkers were the most congenial addition.

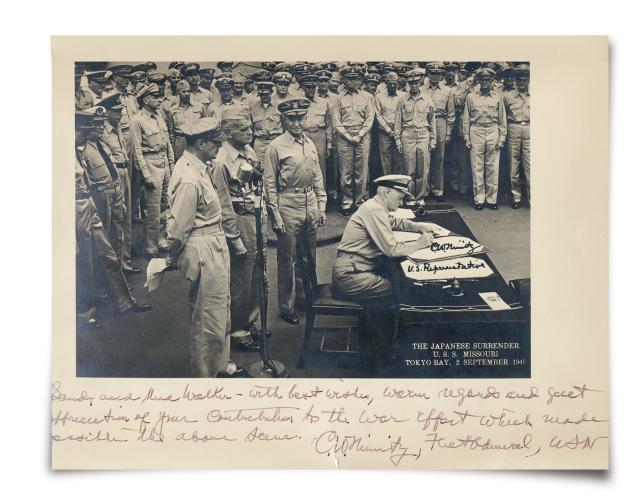

Nimitz became fond of the Walkers’ son, Henry A. “Hanko” Walker Jr., who had been applying for a commission in the Navy but was repeatedly rejected for nearsightedness. “Through the intervention of Nimitz,” Hanko wrote, “I was finally granted a Navy commission.”8 Also, through the assistance of the admiral, he was detailed to the battleship USS Missouri (BB-63), where the Japanese surrender would later take place.

After Nimitz moved his command to Guam in January 1945, Lamar wrote that nearly all the island plants had been destroyed by the “pre-invasion bombardment. Admiral Nimitz was very anxious to have the island reforested.” Accordingly, Nimitz asked the Walkers to send him “any spare seeds of flowering trees, monkey pod trees, lichee nut seeds etc. that you may have.”9

For months, the Walkers gathered fruit trees, maidenhair ferns, bird of paradise, gingers, orchids—seeds and seedlings—and loaded them on board the regular flag plane from Pearl Harbor. On his daily walks, Nimitz planted their monkeypod and other tree seeds. “In later years when you two visit Guam and see all of the fruit and flowering trees and nice plants,” Nimitz wrote, “you can take great satisfaction in your share in this program.”

Along with flora, the Walkers sent Nimitz necessities in short supply on Guam including fresh eggs and “Sparklet” cartridges for creating soda water. Lamar wrote that “the thing that pleases everyone the most is the ‘soda water’. The bottle makes [seltzer] beautifully and the water has all the pep the Admiral wants.” He lamented, however, that they could not make Nimitz’s favorite “old fashion since we have neither oranges nor cherries.” The Walkers soon accommodated him.

In March 1945, Nimitz flew Sandy on the flag plane to Guam for a week where they walked the beaches, swam, and played poker and cribbage. Sandy badly beat Marine Corps Lieutenant General Holland “Howling Mad” Smith in cribbage but “had great difficulty in collecting many cribbage winnings,” Nimitz wrote, because the “General is indeed a tough egg, either as a cribbage opponent or as a battle opponent, as the Japs well know.”

During the days, Sandy and Nimitz fished from a 15-ton, 45-foot Chris Craft cabin cruiser the commanding general of the U.S. Army Air Forces had given Nimitz, who christened it “Catherine—for my sweetheart.”10

After Japanese Emperor Hirohito announced he would unconditionally surrender, the ceremonies were set for 1045, 2 September on board the Missouri. When Nimitz boarded the battleship, the loudspeaker requested the presence of Lieutenant Henry Walker in the wardroom. Hanko reckoned that Nimitz had sent for him.

The wardroom was initially empty. Suddenly Nimitz and Admiral William “Bull” Halsey entered from the starboard doorway, and MacArthur came from the port side.

“MacArthur, with his rich voice, went up to Chester, clasped his hand, and said, ‘Chester.’ He took his other hand and put it on Halsey’s and said, ‘Bill. Chester. This is the day toward which we have strived for so long.’

“They stood there for a frozen moment. It was history, boy. And there I was alone watching it.”

Shortly afterward, “Halsey took MacArthur to his flag officer’s quarters. Nimitz saw me and said, ‘Oh, Henry, I saw your parents two weeks ago and they’re fine. When the Missouri comes through Guam, you’ll dine with me at my quarters.’ Then he looked at me and said, ‘Henry, where the hell are your collar bars?’

“I replied, ‘Oh, Sir, I left them in my room.’”

Remonstrating, the five-star fleet admiral told Hanko, “Go get your collar bars. We may sign the surrender without neckties, but we sure as hell will wear the insignia of our rank.”

Then, the gentlemanly Nimitz shook Hanko’s hand, “smiled his wintry smile and followed Halsey and MacArthur.”

A month after the surrender, Nimitz was back in Hawaii. For Navy Day, 27 October 1945, the Daughters and Sons of Hawaiian Warriors were going to invest Nimitz as a “High Chief of Hawaii” on the steps of ‘Iolani Palace. Nimitz wanted to give a speech in Hawaiian. Because Sandy grew up speaking fluent Hawaiian and Una had a conversational understanding of the language, he asked for their help.

On the appointed day, a yellow flower cape was draped over Nimitz’s shoulders before a crowd of thousands. He raised a small card on which Una had typed Nimitz’s words in Hawaiian:

E na hoaloha Maikai o Hawai`i, Nei, Ke Haawi Aku Nei Au, I Kuu Hoomaikai Piha, Ame Kuu Aloha Nui Loa, Ia Oukou Apau, Aloha, Aloha Kakou.

(To my good friends of dear Hawaii, I give my overflowing thanks and my very fullest aloha. Aloha, aloha for all of us.)

When I was troubled as a child, my grandparents and mother soothed me with a Hawaiian word for patience that gracefully rolls off the tongue like long ocean swells—Ho’omanawanui: All things will work out in the fullness of time. My grandparents passed that word on to Nimitz before he took command of the Pacific Fleet in December 1941, because he needed a lot of patience with his fleet under water.

Now we know what he meant when Nimitz told the press, “You asked several questions about the future, many of them no doubt pressing. . . . I’m a Kama‘aina myself, and I’d like to reply in a Hawaiian word. This word is ho’omanawanui, meaning, ‘Let time take care of the situation.’”11

It did. And, as Nimitz’s grandsons, Chet and Dick Lay, told me, the Walkers provided Nimitz with a “refuge from the stresses of high command” where he “could walk, swim, dine and play poker”—his “own private USO.”

1. Kama‘aina means “child of the earth”—literally, born in Hawaii. Colloquially, it also describes someone who has lived in Hawaii for a long time.

2. CAPT Michael A Lilly, USN (Ret.), Nimitz at Ease (Mt. Vernon, WA: Stairway Press, 2019).

3. E. B. Potter, Nimitz (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1986), 367.

4. Letter to Catherine, 13 February 1945, U.S. Naval Academy Archives.

5. James D. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal (New York: Bantam Books, 2012), 10.

6. Letter to Catherine, 21 January 1945, U.S. Naval Academy Archives.

7. Interview with Hal Lamar, 3 May 1970, by John T. Mason Jr., U.S. Naval Institute, 20.

8. Henry A. Walker Jr., Memoirs (Self-published, 1990), 34.

9. H. Arthur Lamar, I Saw Stars (Fredericksburg, TX: Admiral Nimitz Foundation, 1985), 27.

10. Letter to Catherine, 3 January 1945, U.S. Naval Academy Archives; and interview with Hal Lamar, 56–57.

11. Honolulu Star Bulletin, 1 January 1942, 1.