“WARNING! WARNING! STRANGE SHIP ENTERING HARBOR.” In Savo Sound at 0146 on the morning of 9 August 1942, lookouts on board the destroyer USS Patterson (DD-392) sighted an unidentified ship to the northwest against the gloom of a rain squall. The Patterson’s captain, Commander Frank R. Walker, immediately sounded the alarm. He notified the cruisers in company, HMAS Canberra and the USS Chicago (CA-29), by blinker light and hoped to reach the destroyer USS Bagley (DD-386), in the darkness to starboard, by TBS radio.

As the Patterson’s crew came to general quarters, Walker rang up maximum speed and swung to port, unmasking gun and torpedo batteries. The unidentified ship was not alone; lookouts now reported three ships in column, all Japanese cruisers. They were less than 5,000 yards away and had already opened fire. Somehow they had made it past the destroyers USS Blue (DD-387) and Ralph Talbot (DD-390), the radar pickets outside Savo Sound. Walker repeated his warning and sent it to all the Allied ships in the sound. The Patterson fired two starshell spreads to illuminate the enemy before switching to service projectiles. The range was down to 2,000 yards.

Two enemy searchlights fixed on the Patterson. A hit near gun number four ignited ready service ammunition, and fire enveloped the after part of the ship. Walker zigzagged to throw off the enemy’s aim as a torpedo narrowly missed astern. The Patterson settled to an easterly course, heading back into the sound. Observers thought she hit one of the enemy cruisers before they rounded Savo Island and turned their attention to the north.

The Allied northern group was the enemy’s next objective. The USS Quincy (CA-39) was one of three cruisers in that group. Walker’s warning had sent her crew rushing to general quarters, but the reason for the alarm was unclear. Her gunnery officer, Lieutenant Commander Harry B. Heneberger, realized enemy ships were closing only when searchlights illuminated the Quincy. Japanese shells began straddling her, the Astoria (CA-34), and the Vincennes (CA-44) before their crews had secured for action.

The Quincy was hit on the main deck aft as Heneberger tried to bring his guns on target. He fired a salvo with all nine guns before additional hits jammed turret three and started a fire amidships. Heneberger reported that “the ship was repeatedly hit by large and small caliber shells throughout her full length.”1 Japanese cruisers steamed past on both sides, firing as they went. The Quincy’s fore turrets fired twice more before turret two exploded and turret one was knocked out. Debris crashed down on the forward main battery director, jamming it in place. Heneberger lost communication with the rest of the ship.

When he came down from the director, Heneberger saw that the situation at the ship’s control stations was even worse. Practically everyone on the bridge had been killed. Battle two was wiped out. Central Station reported a torpedo hit and then rapidly filled with water; no one made it out. Another torpedo opened the Quincy’s two after fire-rooms to the sea. Steam pressure was lost and the cruiser slowed. The forecastle was awash, the “hangar and well deck [were a] blazing inferno,” and the Quincy was “listing rapidly to port.” Heneberger ordered the crew to abandon ship. About a minute later, she capsized, the first ship to sink into the body of water that became known as “Ironbottom Sound.”2

Multiple Engagements, Recurring Themes

The Battle of Savo Island was the first major night battle fought during the six-month struggle for Guadalcanal. Prompted by the landing of Major General Alexander A. Vandegrift’s 1st Marine Division at Guadalcanal on 7 August 1942, Vice Admiral Gunichi Mikawa’s seven cruisers and one destroyer entered Ironbottom Sound south of Savo Island, engaged the Patterson and the southern group, and then attacked the Quincy and the northern group. Mikawa’s ships sank four cruisers—the Quincy, Astoria, Vincennes, and Canberra—and damaged the Chicago before withdrawing in the darkness.

Mikawa failed to attack Rear Admiral Richmond K. Turner’s amphibious forces, but, deprived of most of his escort strength and anticipating further attacks, Turner withdrew before unloading the rest of the supplies and ammunition for Vandegrift’s Marines. In the coming weeks, they would struggle to maintain their foothold as the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) asserted its dominance of the waters off Guadalcanal.

Resupply and reinforcement were the deciding factors in the struggle for the island, and they depended on securing the sea and sky. Allied forces maintained a fragile aerial superiority over Guadalcanal because Vandegrift’s Marines possessed “Henderson Field.”3 Captured on the day of the landings, the airfield was operational two weeks later. Its planes contested Japanese incursions during the day, but at night, the IJN controlled the seas.

Four more battles were fought to contest that control: the Battle of Cape Esperance, the First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, the Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal, and the Battle of Tassafaronga. In each, themes from the Battle of Savo Island repeated. Ships appeared suddenly out of the darkness; surprise conferred a decisive advantage; close-range gunfire was devastating; IJN torpedoes were lethal. Although U.S. Navy radars conferred an advantage in these battles, their limitations were poorly understood and procedures for their use varied widely. These conditions tested both U.S. and Japanese doctrine and tactics. Both navies had trained and prepared for night combat, but while the IJN placed great reliance on torpedoes, the U.S. Navy emphasized its guns and the individual initiative of ship and formation commanders. The confused, close-range battles of October and November 1942 allowed the U.S. Navy to leverage these strengths.4

Battle of Cape Esperance

Under pressure from Admiral Chester W. Nimitz to contest IJN dominance of the waters off Guadalcanal, Vice Admiral Robert L. Ghormley, Commander of the South Pacific Area, formed a surface action group under Rear Admiral Norman Scott. Scott drilled the four cruisers and five destroyers of Task Force 64 in tactics that reflected the perceived lessons of Savo Island. He kept them in a compact line of battle, a “double header” formation designed to permit rapid action to either flank.5

When Ghormley sent the 164th Infantry Regiment of the U.S. Army’s Americal Division to Guadalcanal, he ordered Scott to protect the convoy by seeking out and destroying enemy ships. On 11 October, an IJN formation was sighted approaching the island, and Scott moved to intercept. He positioned Task Force 64 outside the northwestern entrance to Ironbottom Sound and athwart Rear Admiral Arimoto Goto’s line of approach. Goto’s mission was to “deluge Henderson Field with 8-inch shells” from his three heavy cruisers; two destroyers provided escort.6

After reversing course at 2333 to keep his ships athwart the entrance to the sound, Scott’s formation lost cohesion when the van destroyers and cruisers turned simultaneously. As reports of approaching enemy forces began to arrive, Scott was unsure if his van destroyers, led by Captain Robert G. Tobin in the USS Farenholt (DD-491), had been misidentified.

His subordinates had no illusions. The new SG search radars on board the USS Helena (CL-50) and Boise (CL-47) had been tracking Goto’s ships. Their fire-control radars were on target and fire-control solutions were ready. The cruisers San Francisco (CA-38) and Salt Lake City (CA-25) also had radar fixes on Goto. When the enemy ships became visible to the naked eye, Captain Gilbert C. Hoover, the Helena’s commanding officer, felt he could wait no longer. He opened fire at 2346. Other cruisers followed suit. Unaware of the close range of Goto’s ships, Scott was taken by surprise. So was Goto. His last order before being mortally wounded was to flash recognition signals, mistakenly believing that another group of IJN ships was firing on him.7

Scott feared his cruisers were firing on his destroyers and ordered a cease-fire. His ships paused, but only to be sure of their targets. By 2351, Scott had recognized the situation and ordered his ships to commence firing once more. In the brief lull, the Aoba reversed course to starboard and made smoke, convincing some observers she had sunk. The cruiser Furutaka was next in line. As she followed the Aoba, U.S. gunners latched onto her and scored many hits. The Kinugasa, Goto’s third cruiser, turned to port and avoided the Furutaka’s fate.

Destroyers from both sides found themselves between the lines. Tobin tried to get the Farenholt past Scott’s cruisers and back in position at the front of the formation, but she was hit and forced to retire. Lieutenant Commander Edmund B. Taylor took the USS Duncan (DD-485) on a lone torpedo attack. Caught “in the crossfire between the Japanese cruiser and our battle line,” the Duncan was hit by both sides, crippled, and sunk.8 The Fubuki, on the starboard side of Goto’s formation and closest to the U.S. line, was targeted and sunk by the San Francisco and Boise.

Around midnight, Scott regrouped and changed course to pursue the retreating enemy. The Kinugasa put a tight salvo in the San Francisco’s wake, but the Boise’s use of a searchlight and rapid gun flashes made her a better target; a shell that landed short tunneled through the water, penetrated her hull, and exploded in the magazine between turrets one and two.9 Flames shot through both turrets and climbed high above her superstructure, but she would survive. So would the Aoba. The Furutaka would not. The Kinugasa escaped largely unscathed.

Scott believed he had won a major victory and claimed damage that far exceeded actual results. However, the IJN maintained control of the waters off Guadalcanal. Two nights after Scott’s victory, the battleships Kongo and Haruna fired nearly 1,000 shells into Vandegrift’s perimeter. “The bombardment,” as the Marines called it, devastated Henderson Field and covered the approach of a Japanese reinforcement convoy. It arrived the following night while the cruisers Chokai and Kinugasa shelled Vandegrift and his men.

First Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

Admiral Nimitz realized that he needed more aggressive leadership if he was to triumph at Guadalcanal. He replaced Vice Admiral Ghormley with Vice Admiral William F. Halsey Jr. Halsey began “throwing punches” almost immediately.10 After Halsey’s carriers thwarted a Japanese offensive at the 25–27 October Battle of the Santa Cruz Islands, he moved to reinforce Vandegrift, sending Rear Admiral Turner to Guadalcanal with the Army’s 182nd Regiment. Meanwhile, Admiral Isoroku Yamamoto prepared a new convoy with 11 transports. These two reinforcement efforts would collide in mid-November.

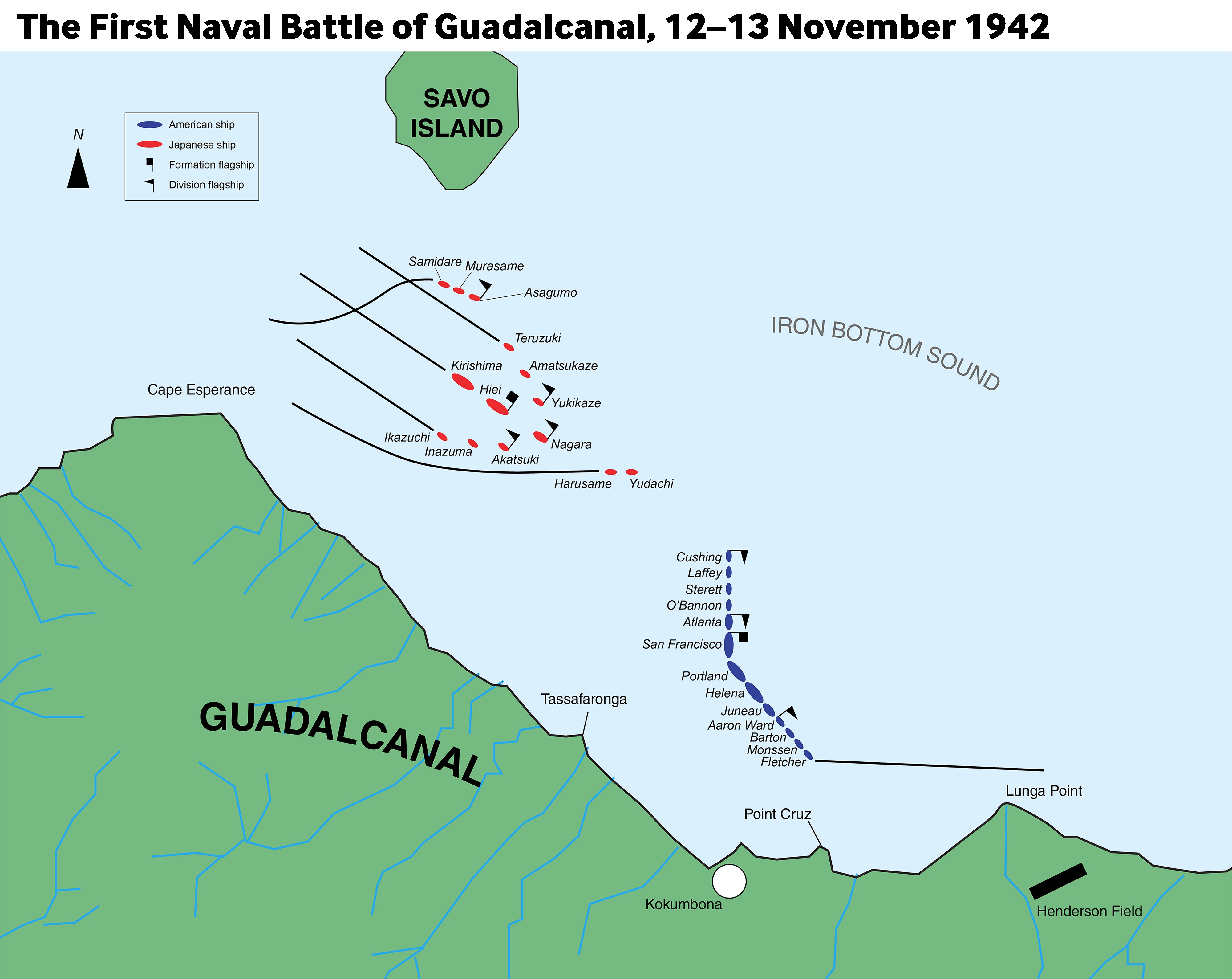

By the evening of 12 November, Turner’s reinforcements were safely ashore on Guadalcanal, but the Japanese countermove was on its way. Vice Admiral Hiroaki Abe was intent on replicating “the bombardment” with the battleships Hiei and Kirishima. Halsey’s major forces were too far away to intervene. As Turner withdrew, he consolidated two groups of screening forces, one under Rear Admiral Scott and the other under Rear Admiral Daniel J. Callaghan, and sent them back into Ironbottom Sound. Callaghan was senior to Scott, so he assumed command of the mixed group of five cruisers and eight destroyers.

Callaghan distributed no battle plan. Like Scott, he kept his ships in a single line to ease control and placed cruisers in the center and destroyers in the van and rear. Although he did not share his intentions beyond his flagship San Francisco’s bridge, Callaghan resolved to be aggressive. He knew he was outnumbered and outgunned—and that the key to victory at Guadalcanal was control of the sea and the sky. Callaghan was determined to prevent the bombardment and keep the planes at Henderson Field flying.

As Callaghan’s ships moved through the sound, the SG radar of the Helena, fourth cruiser in line, detected “two contacts,” bearing 310 degrees, 31,900 yards away at 0126.11 Callaghan immediately set course directly for the enemy. As additional contact reports gave him the course and speed of Abe’s formation, Callaghan maneuvered to intercept, ordering course 000 at 0135. The two forces soon collided in the darkness.

Commander Thomas M. Stokes, commanding Callaghan’s van destroyers, sighted enemy destroyers and received permission to fire torpedoes. As the lead destroyer USS Cushing (DD-376) swung to port to unmask her torpedo battery, Callaghan’s van began to lose cohesion. Rear Admiral Scott’s flagship Atlanta (CL-51), the first of the cruisers, turned left to avoid colliding with the destroyers. Callaghan attempted to regain control by putting his plan in motion. He ordered Stokes and Captain Robert G. Tobin, commanding the rear destroyers, to take course 000 and head through the enemy formation. Callaghan turned the San Francisco to port, came to course 280, and ordered the large cruisers Portland (CA-33) and Helena to follow. He hoped to bring them into action at close range with Abe’s battleships.

Callaghan ordered his ships to open fire, Japanese searchlights came on, and a chaotic close-range brawl erupted as both formations disintegrated. “The tactical situation became utterly confused.”12 Searchlights fixed on the Atlanta, and both sides targeted her. Eight-inch shells from the San Francisco likely killed Scott. A torpedo hit in the Atlanta’s forward engine room knocked out most of her power. Callaghan’s van destroyers battled their opposite numbers before closing Abe’s flagship Hiei. The Laffey (DD-459) passed within ten yards of the battleship, blasting away with every gun that could bear. Tobin’s rear destroyers followed suit, except for the Barton (DD-599), which vanished in a brilliant explosion. As Callaghan closed the range, he issued a confusing order to “cease fire,” intended to mask the approach of his cruisers.13 Only the San Francisco made it. The Portland’s stern was shattered by a torpedo, sending her cruising in circles; she only fired four salvoes at the Hiei. The Helena was distracted by numerous targets and, at one point, her three batteries—main, secondary, and antiaircraft—were in action against three separate targets.

The San Francisco and Hiei engaged each other from close range. Callaghan was killed; his flag captain, Captain Cassin Young, was mortally wounded. Lieutenant Commander Herbert E. Schonland quickly became the San Francisco’s senior surviving officer. He oversaw damage control efforts from belowdecks and left the conn to Lieutenant Commander Bruce McCandless, the only officer on the bridge still standing. Together with the surviving crew members, they brought the San Francisco to safety.

Callaghan’s plan worked, but at great cost. The Atlanta was lost along with the destroyers Cushing, Laffey, Barton, and Monssen (DD-436). The cruiser Juneau (CL-52) was damaged and was sunk by a torpedo from the submarine I-26 the next day. The Portland and San Francisco were heavily damaged. On the Japanese side, the battleship Hiei was too crippled to withdraw; after a series of American air attacks on the 13th, she was scuttled. Two destroyers, the Akatsuki and Yudachi, also were sunk. Yamamoto delayed the reinforcement convoy, hoping a cruiser bombardment the next night would disable the airfield. It did not. Planes from Henderson Field combined with those from the USS Enterprise (CV-6) to sink the retiring Kinugasa and four of the approaching transports. Three others were damaged. By that evening, only four Japanese transports were still on their way to Guadalcanal.

Second Naval Battle of Guadalcanal

To make sure they arrived safely, Yamamoto planned another bombardment. Vice Admiral Nobutake Kondo would shell Henderson Field with the battleship Kirishima and heavy cruisers Atago and Takao the night of 14 November. To oppose them, Halsey sent Task Force 64 under Rear Admiral Willis A. Lee into Ironbottom Sound. Lee had the battleships USS Washington (BB-56) and South Dakota (BB-57) along with four destroyers. Unlike Callaghan and Scott, he had his destroyers to operate independently as an advance screen ahead of his heavy ships.

Lee knew the risk of operating battleships in narrow waters at night. He also knew that his greatest advantage was his gunnery. In 1920, Lee had won seven Olympic medals for marksmanship, five of them gold. He understood the intricacies of naval guns and radars and had helped his flagship Washington achieve a high state of efficiency through practice and regular drills.14

Lee used his guns to prevent the Japanese sweeping unit from interfering with the main action. The SG radars on board the battleships detected the sweepers east of Savo Island just before 2300. After visual confirmation and developing a fire-control solution, Lee had his battleships open fire. Despite claims of hits, the light cruiser and two destroyers of the sweeping unit were unscathed. They made smoke and opened the range.

In the meantime, Kondo’s screening group had rounded Savo Island from the west. A melee developed as Lee’s van destroyers sacrificed themselves to screen the battleships. The USS Benham (DD-397) was stopped short by a torpedo that shattered her hull. The Preston (DD-379) was heavily hit and sank quickly after a large explosion. The Walke (DD-416) was crippled by a torpedo that tore off her bow and set off her forward magazine. In exchange, Lee’s screen crippled the enemy destroyer Ayanami. Fires spread to oxygen tanks in her torpedo battery, triggering an explosion that broke her in two. At 2348, Lee ordered his destroyers to retire; the Gwin (DD-433) was the only one that could comply.

Captain Glenn B. Davis took the battleship Washington to port, keeping the burning van destroyers between him and the enemy. Captain Thomas L. Gatch’s South Dakota, which had experienced a major power failure, went the other way and was silhouetted against the flames. Four searchlights from Kondo’s flagship Atago fixed on her. The Kirishima, Atago, and Takao immediately opened fire. Shells tore into the South Dakota’s superstructure, damaging lightly protected installations and complicating her electrical problems. Gatch’s ship was blind and practically helpless, unable to bring her 16-inch guns on target.

Lee knew the Washington’s gunners had a solution on a large target that they had been tracking since 2335, but he was hesitant to open fire. He wanted to be certain he was about to fire on the enemy and not the South Dakota. The Washington’s SG radar was mounted on the front of the main battery control tower; it had a large blind spot to the rear. The South Dakota had been in that blind spot when the battleships were cruising in line, but she had since drifted out to starboard. Was she the “target” his gunners were tracking?

Lee held fire to clarify the situation, but when the Atago’s searchlights came on, all doubt in Lee’s mind vanished. He immediately realized the relative positions of the South Dakota and the enemy. The Washington opened fire on the Kirishima. Using the best radar-assisted gunnery procedures, Commander Harvey Walsh, the Washington’s gunnery officer, used radar ranges, visual bearings, and a walking ladder to maximize hits.15 Within seven short minutes, the Kirishima was mortally wounded and sinking. Another attempt to bombard Henderson Field had failed.

Battle of Tassafaronga

After the battles of mid-November, the Japanese never mounted another major effort to retake Guadalcanal, but they did try to resupply their garrison. One attempt led to the last major surface action of the campaign, the Battle of Tassafaronga, fought on the night of 30 November. Rear Admiral Raizo Tanaka brought eight destroyers to Ironbottom Sound; Halsey sent Task Force 67, commanded by Rear Admiral Carleton H. Wright, to intercept.

Wright was new to his command; he relieved Rear Admiral Thomas C. Kinkaid on 28 November and adopted Kinkaid’s battle plan. Kinkaid planned to send his destroyers ahead for torpedo attacks while his five cruisers remained more distant and opened fire from “between 10,000 and 12,000 yards” using fire-control radars. To prevent a confused melee and hopefully avoid enemy torpedoes, Kinkaid expected to keep his cruisers at least 6,000 yards from the enemy.16

Wright tried to adhere to the plan as he approached from the east and encountered Tanaka’s destroyers. Commander William Cole’s Fletcher (DD-445) led Wright’s four van destroyers; Cole used his ship’s SG radar to navigate to attack position and, at 2316, requested permission to fire torpedoes. Wright hesitated, and by the time he gave the order to fire at 2321, the Fletcher and the other destroyers were out of position. Some of them fired anyway. Before all their torpedoes were in the water, Wright ordered his cruisers to open fire.17 They brought their guns on to the best radar target, the destroyer Takanami, which they hit repeatedly and set ablaze.

Tanaka reacted quickly and ordered a torpedo attack. Captain Torajiro Sato, at the head of the Japanese column, took his four ships ahead at moderate speed, kept them hidden in the shadow of Guadalcanal, and then turned to launch torpedoes. By 2333, 44 torpedoes were headed toward Wright’s cruisers from six of Tanaka’s ships.18

The flagship USS Minneapolis (CA-36) was hit by two torpedoes and “virtually immobilized.”19 Another torpedo tore off the bow of the New Orleans (CA-32) forward of turret two. The ocean surrounding the two ships was a “mass of flame from the gasoline in their forward storage tanks.”20 The Pensacola (CA-24) passed the damaged cruisers on the engaged side before returning to the base course; a torpedo struck amidships, sending fuel oil onto the mainmast, which then ignited. The Honolulu (CL-48) accelerated, passed behind the damaged cruisers, and “maneuvered radically.”21 She was the only cruiser unscathed.

The Northampton (CA-26) also passed to the disengaged side but did not accelerate or maneuver so well. Two torpedoes hit her port side and fires erupted “over the entire after part of the ship.”22 They kept the crew from bringing the flooding under control. The Northampton sank at 0304. The other cruisers survived.

Tanaka had devastated Wright’s cruiser column, but Wright claimed serious enemy losses in return, estimating that he had sunk two light cruisers and seven destroyers. Only the Takanami was lost. Fire-control teams on Wright’s cruisers had been deceived by a weakness of the FC radar. It was easy to lose targets among shell splashes and miss that they had turned away. When the shooting stopped and “targets” disappeared, they were erroneously considered “sunk.”23 Nevertheless, Wright accomplished his primary goal. None of the supplies Tanaka had brought to Ironbottom Sound made it to the Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

‘Aggressiveness and Individual Initiative’

The five major battles off Guadalcanal were a test of U.S. and Japanese tactics and doctrine. Although many of the battles were tactical defeats for the U.S. Navy, its forces triumphed in the campaign because of their ability to thwart Japanese strategic designs. That ability rested on prewar tactical principles emphasizing aggressiveness and individual initiative.24 In the confused night battles, formations regularly dissolved in the darkness and lost cohesion.

As battles became contests of individual ships, bold individual decisions by U.S. naval officers and men allowed them to capitalize on momentary opportunities. Hoover opening fire at Cape Esperance, Callaghan deliberately seeking a melee, and Lee’s aggressive use of battleship gunfire kept Henderson Field’s pilots flying, limiting Japanese resupply and reinforcement. Victory in the “inferno” of Ironbottom Sound was costly—but it allowed Halsey to win the campaign and Nimitz to seize the initiative in the Pacific.25

1. “Preliminary Report of Engagement the night of 9 August, 1942, off Guadalcanal Island,” LCDR Harry B. Heneberger, USN, 12 August 1942.

2. “Preliminary Report of Engagement the night of 9 August, 1942.”

3. Named after Maj Lofton Henderson, USMC, who died leading his dive-bombing squadron against the Japanese at Midway.

4. Trent Hone, Learning War: The Evolution of Fighting Doctrine in the U.S. Navy, 1898–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 2018), 163–207.

5. “Memorandum for Task Group Sixty-Four Point Two,” Rear Admiral Norman Scott, 9 October 1942; “Action off Savo Island, Night of 11–12 October; report of,” Gilbert C. Hoover, Commanding Officer, U.S.S. Helena, 20 October 1942.

6. Richard B. Frank, Guadalcanal: The Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle (New York: Random House, 1990), 295.

7. The other IJN formation in the sound that night was a pair of seaplane carriers that were bringing guns, ammunition, and equipment to Japanese forces on Guadalcanal.

8. “Detailed Report of the Action of the U.S.S. Duncan (485) During the Engagement with Enemy Japanese Forces off Savo Island, Solomon Island Group, during the Night of 11–12 October, 1942,” Commanding Officer, EX-USS Duncan, 16 October 1942.

9. “Action off Cape Esperance on night of 11–12 October 1942, report of” Commanding Officer, USS Boise; this was a Suichudan (underwater shot) shell, designed to operate this way. See David C. Evans and Mark R. Peattie, Kaigun: Strategy, Tactics, and Technology in the Imperial Japanese Navy, 1887–1941 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1997), 263–66.

10. Personal Letter, Halsey to Nimitz, 31 October 1942.

11. “Action Report—Night Action—November 12, 13, 1942; forwarding of,” Commanding Officer, USS San Francisco, 16 November 1942; “Action off North Coast Guadalcanal, Early Morning of November 13, 1942; report of,” Commanding Officer, USS Helena, 15 November 1942.

12. C. Raymond Calhoun, Tin Can Sailor: Life Aboard the USS Sterett, 1939–1945 (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1993), 76.

13. Hone, Learning War, 195–96.

14. Edwin B. Hooper, Letter to Mr. Ryan, 10 October 1985.

15. “Action Report, Night of November 14–15, 1942,” Commanding Officer, USS Washington, 27 November 1942.

16. “Operation Plan No. 1-42,” Commander Task Force 67, 27 November 1942.”

17. Russell Sydnor Crenshaw Jr., South Pacific Destroyer: The Battle for the Solomons from Savo Island to Vella Gulf (Annapolis, MD: Naval Institute Press, 1998), 15.

18. Frank, Guadalcanal, 509–10.

19. “Report of Action—Night of November 30–December 1, 1942,” Commander Task Unit Sixty-Seven Point Two Point Three, 6 December 1942.

20. Report on Action off Cape Esperance, Night of November 30, 1942,” Commander Task Force Sixty-Seven, 9 December 1942.

21. “Action Report—Engagement off Savo Island, Night of November 30th–December 1st, 1942—USS Honolulu,” Commanding Officer, 4 December 1942.

22. Samuel Eliot Morison, History of United States Naval Operations in World War II, vol. 5: The Struggle for Guadalcanal, August 1942–February 1943 (Boston: Little, Brown, 1949), 307.

23. Hone, Learning War, 205.

24. Hone, Learning War, 163–207.

25. James D. Hornfischer, Neptune’s Inferno: The U.S. Navy at Guadalcanal (New York: Bantam Books, 2011); the term “inferno” is borrowed from the title.